Myoclonic Status Epilepticus in Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway

JOHNS HOPKINS ALL CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway 1 Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway Table of Contents 1. Rationale 2. Background 3. Diagnosis 4. Labs 5. Radiologic Studies 6. General Management 7. Status Epilepticus Pathway 8. Pharmacologic Management 9. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring 10. Inpatient Status Admission Criteria a. Admission Pathway 11. Outcome Measures 12. References Last updated: July 7, 2019 Owners: Danielle Hirsch, MD, Emergency Medicine; Jennifer Avallone, DO, Neurology This pathway is intended as a guide for physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners and other healthcare providers. It should be adapted to the care of specific patient based on the patient’s individualized circumstances and the practitioner’s professional judgment. 2 Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway Rationale This clinical pathway was developed by a consensus group of JHACH neurologists/epileptologists, emergency physicians, advanced practice providers, hospitalists, intensivists, nurses, and pharmacists to standardize the management of children treated for status epilepticus. The following clinical issues are addressed: ● When to evaluate for status epilepticus ● When to consider admission for further evaluation and treatment of status epilepticus ● When to consult Neurology, Hospitalists, or Critical Care Team for further management of status epilepticus ● When to obtain further neuroimaging for status epilepticus ● What ongoing therapy patients should receive for status epilepticus Background: Status epilepticus (SE) is the most common neurological emergency in children1 and has the potential to cause substantial morbidity and mortality. Incidence among children ranges from 17 to 23 per 100,000 annually.2 Prevalence is highest in pediatric patients from zero to four years of age.3 Ng3 acknowledges the most current definition of SE as a continuous seizure lasting more than five minutes or two or more distinct seizures without regaining awareness in between. -

The Migraine-Epilepsy Syndrome

medigraphic Artemisaen línea Arch Neurocien (Mex) Vol 11, No. 4: 282-287, 2006 The Migraine- Epilepsy Syndrome Arch Neurocien (Mex) Vol. 11, No. 4: 282-287, 2006 Artículo de revisión ©INNN, 2006 de caso The migraine-epilepsy syndrome Enrique Otero Siliceo†, Fernando Zermeño EL SINDROME MIGRAÑA-EPILEPSIA represent a neural exitation. Since that the glutamate has in important rol in both patologys depending of the part of the brain more affected the symptoms might RESUMEN vary from visual to abdominal phemomena. La migraña y la epilepsia tienen varios puntos en común Key words: migraine epilepsy, EEG abnormalities, sintomática clínica y genéticamente lo que ha sido glutamate, diagnosis. postulado por más de cien años. El fenómeno referido como migraña-epilepsia sugiere que exista una he first steps of a practical, approach by patofisiología común. El síndrome de migraña o physicians in recognizing and treating neuro- epilepsia tiene fenómenos comunes de dolor adominal T logic diseases are to recognithat there are jaqueca anormalidades del EE y respuesta a droga various overlaps between migraine and epilepsy. antiepilépticas. En ocasiones el paciente puede tener Epileptic seizures and classic migraine episodes may un ataque migrañoso o una convulsión o en otras occur in the same patient. Migraine and epilepsy share ambas. La comorbilidad puede explicarse por estados several genetic, clinical, evolutive and neurophysio- de hiperrexcitabilidad neural. Alteraciones electroen- logic features. A relationship between epilepsy and cefalográficas son comunes en estos estados. En migraine has been postulated for over a hundred years apariencia el glutamato tiene un papel importante tanto and the syndrome of Migraine-Epilepsy illustrates this en la migraña como en la epilepsia. -

Migraine Triggered Seizures and Epilepsy Triggered Headache and Migraine Attacks: a Need for Re-Assessment

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PubMed Central J Headache Pain (2011) 12:287–288 DOI 10.1007/s10194-011-0344-2 COMMENTARY Migraine triggered seizures and epilepsy triggered headache and migraine attacks: a need for re-assessment Paul T. G. Davies • C. P. Panayiotopoulos Received: 5 April 2011 / Accepted: 8 April 2011 / Published online: 24 April 2011 Ó The Author(s) 2011. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com In this issue of the Journal, Belcastro and associates review Migralepsy terminology and classification issues for migralepsy, hem- icrania epileptica, post-ictal and ictal headache [1]. They According to the ICHD-II 1.5.5, ‘‘migraine-triggered sei- raise key points such as ictal headache and visual seizures zure (sometimes referred to as migralepsy)’’ denotes an are often misdiagnosed as migraine, ‘‘migralepsy’’ is unli- epileptic seizure that occurs ‘‘during or within one hour kely to exist and an ‘‘epilepsy-migraine sequence’’ is much after a migraine aura’’ [3]. However, the evidence of this more common and well documented than the dominant ‘‘migraine-seizure’’ sequence is weak and the proposed view of a ‘‘migraine-epilepsy sequence’’. Their relevant criterion of 1 h gap between the end of the ‘‘aura’’ and the proposals need appropriate attention by the committee of start of an epileptic seizure is entirely arbitrary the international classification of headache disorders Migralepsy is an old term derived from migra(ine) and (ICHD) as well as the physicians in their clinical practice (epi)lepsy, coined by Dr Douglas Davidson, but mainly because of the consequences that misdiagnosis may have on attributed to Lennox and Lennox, which we quote, ‘‘a patients. -

Clinicians Using the Classification Will Identify a Seizure As Focal Or Generalized Onset If There Is About an 80% Confidence Level About the Type of Onset

GENERALIZED ONSET SEIZURES Generalized onset seizures are not characterized by level of awareness, because awareness is almost always impaired. Generalized tonic-clonic: Immediate loss of Generalized epileptic spasms: Brief seizures with awareness, with stiffening of all limbs (tonic phase), flexion at the trunk and flexion or extension of the followed by sustained rhythmic jerking of limbs and limbs. Video-EEG recording may be required to face (clonic phase). Duration is typically 1 to 3 minutes. determine focal versus generalized onset. The seizure may produce a cry at the start, falling, tongue biting, and incontinence. Generalized typical absence: Sudden onset when activity stops with a brief pause and staring, Generalized clonic: Rhythmical sustained jerking of sometimes with eye fluttering and head nodding or limbs and/or head with no tonic stiffening phase. other automatic behaviors. If it lasts for more than These seizures most often occur in young children. several seconds, awareness and memory are impaired. Recovery is immediate. The EEG during these seizures Generalized tonic: Stiffening of all limbs, without always shows generalized spike-waves. clonic jerking. Generalized atypical absence: Like typical absence Generalized myoclonic: Irregular, unsustained jerking seizures, but may have slower onset and recovery and of limbs, face, eyes, or eyelids. The jerking of more pronounced changes in tone. Atypical absence generalized myoclonus may not always be left-right seizures can be difficult to distinguish from focal synchronous, but it occurs on both sides. impaired awareness seizures, but absence seizures usually recover more quickly and the EEG patterns are Generalized myoclonic-tonic-clonic: This seizure is like different. -

Neuropathology Category Code List

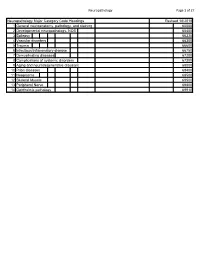

Neuropathology Page 1 of 27 Neuropathology Major Category Code Headings Revised 10/2018 1 General neuroanatomy, pathology, and staining 65000 2 Developmental neuropathology, NOS 65400 3 Epilepsy 66230 4 Vascular disorders 66300 5 Trauma 66600 6 Infectious/inflammatory disease 66750 7 Demyelinating diseases 67200 8 Complications of systemic disorders 67300 9 Aging and neurodegenerative diseases 68000 10 Prion diseases 68400 11 Neoplasms 68500 12 Skeletal Muscle 69500 13 Peripheral Nerve 69800 14 Ophthalmic pathology 69910 Neuropathology Page 2 of 27 Neuropathology 1 General neuroanatomy, pathology, and staining 65000 A Neuroanatomy, NOS 65010 1 Neocortex 65011 2 White matter 65012 3 Entorhinal cortex/hippocampus 65013 4 Deep (basal) nuclei 65014 5 Brain stem 65015 6 Cerebellum 65016 7 Spinal cord 65017 8 Pituitary 65018 9 Pineal 65019 10 Tracts 65020 11 Vascular supply 65021 12 Notochord 65022 B Cell types 65030 1 Neurons 65031 2 Astrocytes 65032 3 Oligodendroglia 65033 4 Ependyma 65034 5 Microglia and mononuclear cells 65035 6 Choroid plexus 65036 7 Meninges 65037 8 Blood vessels 65038 C Cerebrospinal fluid 65045 D Pathologic responses in neurons and axons 65050 1 Axonal degeneration/spheroid/reaction 65051 2 Central chromatolysis 65052 3 Tract degeneration 65053 4 Swollen/ballooned neurons 65054 5 Trans-synaptic neuronal degeneration 65055 6 Olivary hypertrophy 65056 7 Acute ischemic (hypoxic) cell change 65057 8 Apoptosis 65058 9 Protein aggregation 65059 10 Protein degradation/ubiquitin pathway 65060 E Neuronal nuclear inclusions 65100 -

Neuronal Hyperexcitability in a Mouse Model of SCN8A Epileptic Encephalopathy

Neuronal hyperexcitability in a mouse model of SCN8A epileptic encephalopathy Luis F. Lopez-Santiagoa,1, Yukun Yuana,1, Jacy L. Wagnonb, Jacob M. Hulla, Chad R. Frasiera, Heather A. O’Malleya, Miriam H. Meislerb,c, and Lori L. Isoma,c,d,2 aDepartment of Pharmacology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109; bDepartment of Human Genetics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109; cDepartment of Neurology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109; and dDepartment of Molecular and Integrative Physiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 Edited by William A. Catterall, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA, and approved January 17, 2017 (received for review October 12, 2016) Patients with early infantile epileptic encephalopathy (EIEE) experi- include seizure onset between birth and 18 mo of age, mild to se- ence severe seizures and cognitive impairment and are at increased vere cognitive and developmental delay, and mild to severe risk for sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP). EIEE13 [Online movement disorders (11, 13). Approximately 50% of patients are Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) # 614558] is caused by de nonambulatory and 12% of published cases (5/43) experienced novo missense mutations in the voltage-gated sodium channel gene SUDEP during childhood or adolescence (10, 13, 16, 17). SCN8A. Here, we investigated the neuronal phenotype of a mouse Almost all of the identified mutations in SCN8A are missense model expressing the gain-of-function SCN8A patient mutation, mutations. Ten of these mutations have been tested functionally in p.Asn1768Asp (Nav1.6-N1768D). Our results revealed regional transfected cells, and eight were found to introduce changes in the and neuronal subtype specificity in the effects of the N1768D muta- biophysical properties of Na 1.6 that are predicted to result in Scn8aN1768D/+ v tion. -

Myoclonic Atonic Epilepsy Another Generalized Epilepsy Syndrome That Is “Not So” Generalized

EDITORIAL Myoclonic atonic epilepsy Another generalized epilepsy syndrome that is “not so” generalized John M. Zempel, MD, Myoclonic atonic/astatic epilepsy (MAE), first described have shown predominant thalamic activation PhD well by Doose1 (pronounced dough sah: http://www. and default mode network deactivation.6–8 Even Tadaaki Mano, MD, PhD youtube.com/watch?v5hNNiWXV2wF0), is a general- Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, a devastating epileptic ized electroclinical syndrome with early onset charac- encephalopathy with EEG findings of runs of slow terized by myoclonic, atonic/astatic, generalized spike and wave and paroxysmal higher frequency Correspondence to tonic-clonic, and absence seizures (but not tonic activity, has fMRI correlates that are more focal than Dr. Zempel: [email protected] seizures) in association with generalized spike-wave expected in a syndrome with widespread EEG (GSW) discharges. Thought to have a genetic com- abnormalities.9,10 Neurology® 2014;82:1486–1487 ponent that has proven to be complicated,2 MAE EEG-fMRI is maturing as a research and clinical sometimes occurs in children who have otherwise technique. Recording scalp EEG in an electrically been developing normally and has variable outcome. hostile environment is not an easy task. Substantial MAE is typically treated with antiseizure medications technical artifacts, such as changing imaging gradients that are used for generalized epilepsy syndromes, with and ballistocardiogram (ECG-linked artifact observed perhaps a best response to valproate, felbamate, or the in the scalp electrodes), contaminate the EEG signal. ketogenic diet.3,4 However, the relatively distinctive EEG discharges in In this issue of Neurology®, Moeller et al.5 report patients with epilepsy have partially circumvented on the fMRI correlates of GSW discharges as mea- this problem. -

Emergency Department Management of Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome

The Journal of Emergency Medicine, Vol. -, No. -, pp. 1–4, 2016 Ó 2016 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 0736-4679/$ - see front matter http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.10.042 Selected Topics: Psychiatric Emergencies PSYCHIATRIC EMERGENCIES FOR CLINICIANS: EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT MANAGEMENT OF NEUROLEPTIC MALIGNANT SYNDROME Michael P. Wilson, MD, PHD,*† Gary M. Vilke, MD,*† Stephen R. Hayden, MD,* and Kimberly Nordstrom, MD, JD‡§ *University of California at San Diego Medical Center, San Diego, California, †Department of Emergency Medicine Behavioral Emergencies Research (DEMBER) Laboratory, University of California San Diego, San Diego, California, ‡Denver Health Medical Center, Department of Behavioral Health, Psychiatric Emergency Service, Denver, Colorado, and §University of Colorado Denver, School of Medicine, Aurora, Colorado Reprint Address: Michael P. Wilson, MD, PHD, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of California at San Diego Medical Center, 200 West Arbor Drive, Mail Code #8676, San Diego, CA, 92103 , Keywords—altered mental status; neuroleptic malig- What Do You Think is Going on with This Patient? nant syndrome; dystonia; catatonia; rigidity The clinical presentation suggests neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS). Although first described more than 50 years ago, the diagnosis of NMS is primarily CLINICAL SCENARIO clinical (1). A 25-year-old man presents with a recent diagnosis of schizophrenia. He was discharged 1 week earlier from What Key Findings Lead to the Diagnosis? an inpatient psychiatric unit. His mother states that he has been acting ‘‘differently’’ for the past 2 days. He Clues to an NMS diagnosis include a recent diagnosis of a has not been ‘‘making any sense,’’ has felt warm to the psychotic disorder and inpatient psychiatric hospitaliza- touch, and today has been stiff and moving rigidly like tion. -

ILAE Classification and Definition of Epilepsy Syndromes with Onset in Childhood: Position Paper by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions

ILAE Classification and Definition of Epilepsy Syndromes with Onset in Childhood: Position Paper by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions N Specchio1, EC Wirrell2*, IE Scheffer3, R Nabbout4, K Riney5, P Samia6, SM Zuberi7, JM Wilmshurst8, E Yozawitz9, R Pressler10, E Hirsch11, S Wiebe12, JH Cross13, P Tinuper14, S Auvin15 1. Rare and Complex Epilepsy Unit, Department of Neuroscience, Bambino Gesu’ Children’s Hospital, IRCCS, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Rome, Italy 2. Divisions of Child and Adolescent Neurology and Epilepsy, Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester MN, USA. 3. University of Melbourne, Austin Health and Royal Children’s Hospital, Florey Institute, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia. 4. Reference Centre for Rare Epilepsies, Department of Pediatric Neurology, Necker–Enfants Malades Hospital, APHP, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Institut Imagine, INSERM, UMR 1163, Université de Paris, Paris, France. 5. Neurosciences Unit, Queensland Children's Hospital, South Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. Faculty of Medicine, University of Queensland, Queensland, Australia. 6. Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Aga Khan University, East Africa. 7. Paediatric Neurosciences Research Group, Royal Hospital for Children & Institute of Health & Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, Member of European Refence Network EpiCARE, Glasgow, UK. 8. Department of Paediatric Neurology, Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital, Neuroscience Institute, University of Cape Town, South Africa. 9. Isabelle Rapin Division of Child Neurology of the Saul R Korey Department of Neurology, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY USA. 10. Programme of Developmental Neurosciences, UCL NIHR BRC Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, Department of Clinical Neurophysiology, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, London, UK 11. -

Reviews Familial Cortical Myoclonic Tremor and Epilepsy, an Enigmatic Disorder: from Phenotypes to Pathophysiology and Genetics

Freely available online Reviews Familial Cortical Myoclonic Tremor and Epilepsy, an Enigmatic Disorder: From Phenotypes to Pathophysiology and Genetics. A Systematic Review 1 1 2,3 1* Tom van den Ende , Sarvi Sharifi , Sandra M. A. van der Salm & Anne-Fleur van Rootselaar 1 Department of Neurology and Clinical Neurophysiology, Amsterdam Neuroscience, Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2 Brain Center Rudolf Magnus, Department of Neurology and Neurosurgery, University Medical Center, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 3 Stichting Epilepsie Instellingen Nederland (SEIN), Zwolle, The Netherlands Abstract Background: Autosomal dominant familial cortical myoclonic tremor and epilepsy (FCMTE) is characterized by distal tremulous myoclonus, generalized seizures, and signs of cortical reflex myoclonus. FCMTE has been described in over 100 pedigrees worldwide, under several different names and acronyms. Pathological changes have been located in the cerebellum. This systematic review discusses the clinical spectrum, treatment, pathophysiology, and genetic findings. Methods: We carried out a PubMed search, using a combination of the following search terms: cortical tremor, myoclonus, epilepsy, benign course, adult onset, familial, and autosomal dominant; this resulted in a total of 77 studies (761 patients; 126 pedigrees) fulfilling the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Results: Phenotypic differences across pedigrees exist, possibly related to underlying genetic differences. A ‘‘benign’’ phenotype has been described in several Japanese families and pedigrees linked to 8q (FCMTE1). French patients (5p linkage; FCMTE3) exhibit more severe progression, and in Japanese/Chinese pedigrees (with unknown linkage) anticipation has been suggested. Preferred treatment is with valproate (mind teratogenicity), levetiracetam, and/or clonazepam. Several genes have been identified, which differ in potential pathogenicity. Discussion: Based on the core features (above), the syndrome can be considered a distinct clinical entity. -

Lafora Disease Masquerading As Hepatic Dysfunction

Thomas Jefferson University Jefferson Digital Commons Abington Jefferson Health Papers Abington Jefferson Health 8-24-2018 Lafora Disease Masquerading as Hepatic Dysfunction Faisal Inayat Allama Iqbal Medical College Waqas Ullah Abington Jefferson Health Hanan T. Lodhi University of Nebraska at Omaha Zarak H. Khan St. Mary Mercy Hospital Livonia Ghulam Ilyas SUNY Downstate Medical Center Follow this and additional works at: https://jdc.jefferson.edu/abingtonfp See next page for additional authors Part of the Gastroenterology Commons, and the Medical Genetics Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Recommended Citation Inayat, Faisal; Ullah, Waqas; Lodhi, Hanan T.; Khan, Zarak H.; Ilyas, Ghulam; Ali, Nouman Safdar; and Abdullah, Hafez Mohammad A., "Lafora Disease Masquerading as Hepatic Dysfunction" (2018). Abington Jefferson Health Papers. Paper 7. https://jdc.jefferson.edu/abingtonfp/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jefferson Digital Commons. The Jefferson Digital Commons is a service of Thomas Jefferson University's Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL). The Commons is a showcase for Jefferson books and journals, peer-reviewed scholarly publications, unique historical collections from the University archives, and teaching tools. The Jefferson Digital Commons allows researchers and interested readers anywhere in the world to learn about and keep up to date with Jefferson scholarship. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Abington Jefferson Health Papers by an authorized administrator of the Jefferson Digital Commons. For more information, please contact: [email protected]. Authors Faisal Inayat, Waqas Ullah, Hanan T. Lodhi, Zarak H. Khan, Ghulam Ilyas, Nouman Safdar Ali, and Hafez Mohammad A. -

RLS), a Clinical Diagnosis

Liza Ashbrook, MD February 10, 2017 Recent Advances in Neurology Patient 1 This 70-year-old man has restless leg syndrome (RLS), a clinical diagnosis. RLS affects 5-10% of the adult population of European ancestry, though likely only 2-3% come to clinical attention. The cause of RLS is not clear but it is associated with low central iron stores. This is supported by evidence from autopsy studies, CSF analysis, gradient echo MRI and transcranial ultrasound. A family history of RLS is reported in 63-92% of individuals suggesting a strong genetic component as well. RLS is typically separated into intermittent symptoms, defined by fewer than twice/week over a year and chronic symptoms. When symptoms are only bothersome intermittently, such as a long plane flight, medications such as carbidopa/levodopa 25/100 can be very effective, however use more than twice weekly can lead to augmentation. Benzodiazepines and hypnotics are also recommended only for as needed use. Periodic limb movements (PLMs) occur in up to 80% of patients with RLS and are diagnosed by polysomnography. These are stereotyped kicking movements and patients are usually unaware of their presence though bed partners may complain. A small subset of those with PLMs are thought to have periodic leg movement disorder (PLMD), defined by PLMs causing either night time or daytime impairment. Other causes of insomnia and hypersomnia must be ruled out and those with RLS cannot have a diagnosis of PLMD. PLMs are of unclear clinical significance and may be a part of normal aging or an epiphenomenon. RLS and PLMs are commonly confused.