Seizure Ending Signs in Patients with Dyscognitive Focal Seizures*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway

JOHNS HOPKINS ALL CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway 1 Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway Table of Contents 1. Rationale 2. Background 3. Diagnosis 4. Labs 5. Radiologic Studies 6. General Management 7. Status Epilepticus Pathway 8. Pharmacologic Management 9. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring 10. Inpatient Status Admission Criteria a. Admission Pathway 11. Outcome Measures 12. References Last updated: July 7, 2019 Owners: Danielle Hirsch, MD, Emergency Medicine; Jennifer Avallone, DO, Neurology This pathway is intended as a guide for physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners and other healthcare providers. It should be adapted to the care of specific patient based on the patient’s individualized circumstances and the practitioner’s professional judgment. 2 Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway Rationale This clinical pathway was developed by a consensus group of JHACH neurologists/epileptologists, emergency physicians, advanced practice providers, hospitalists, intensivists, nurses, and pharmacists to standardize the management of children treated for status epilepticus. The following clinical issues are addressed: ● When to evaluate for status epilepticus ● When to consider admission for further evaluation and treatment of status epilepticus ● When to consult Neurology, Hospitalists, or Critical Care Team for further management of status epilepticus ● When to obtain further neuroimaging for status epilepticus ● What ongoing therapy patients should receive for status epilepticus Background: Status epilepticus (SE) is the most common neurological emergency in children1 and has the potential to cause substantial morbidity and mortality. Incidence among children ranges from 17 to 23 per 100,000 annually.2 Prevalence is highest in pediatric patients from zero to four years of age.3 Ng3 acknowledges the most current definition of SE as a continuous seizure lasting more than five minutes or two or more distinct seizures without regaining awareness in between. -

Cognitive Impairment: Causes, Diagnosis and Treatment

NEUROLOGY - LABORATORY AND CLINICAL RESEARCH DEVELOPMENTS COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT: CAUSES, DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT No part of this digital document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means. The publisher has taken reasonable care in the preparation of this digital document, but makes no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assumes no responsibility for any errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of information contained herein. This digital document is sold with the clear understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, medical or any other professional services. NEUROLOGY – LABORATORY AND CLINICAL RESEARCH DEVELOPMENTS SERIES Intracranial Hypertension Stefan Mircea Iencean and Alexandru Vladimir Ciurea 2009 ISBN: 978-1-60741-862-7 (Hardcover Book) Intracranial Hypertension Stefan Mircea Iencean and Alexandru Vladimir Ciurea 2009 ISBN: 978-1-60876-549-2 (Online Book) Cerebral Blood Flow Regulation Nodar P. Mitagvaria and Haim (James) I. Bicher 2009 ISBN: 978-1-60692-163-0 Cerebral Ischemia in Young Adults: Pathogenic and Clinical Perspectives Alessandro Pezzini and Alessandro Padovani (Editors) 2009 ISBN: 978-1-60741-627-2 Dizziness: Vertigo, Disequilibrium and Lightheadedness Agnes Lindqvist and Gjord Nyman (Editors) 2009: ISBN 978-1-60741-847-4 Somatosensory Cortex: Roles, Interventions and Traumas Niels Johnsen and Rolf Agerskov (Editors) 2009. ISBN: 978-1-60741-876-4 Cognitive Impairment: Causes, Diagnosis and Treatment Melanie L. Landow (Editor) 2009. ISBN: 978-1-60876-205-7 NEUROLOGY - LABORATORY AND CLINICAL RESEARCH DEVELOPMENTS COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT: CAUSES, DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT MELANIE L. -

The Effect of Temporal Lobectomy Upon Two Cases of an Unusual Form of Mental Deficiency by D

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.17.4.267 on 1 November 1954. Downloaded from J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiat., 1954, 17, 267. THE EFFECT OF TEMPORAL LOBECTOMY UPON TWO CASES OF AN UNUSUAL FORM OF MENTAL DEFICIENCY BY D. W. LIDDELL and D. W. C. NORTHFIELD From Runwtvell Hospital, Wickford, Essex In 1898, when giving the final particulars and the Case Histories necropsy findings of a case of epilepsy which fully Case l.-M. G., aged 18 years, was referred to exemplified dreamy states and automatisms, Hugh- Runwell Hospital from the Royal Eastern Counties lings Jackson (1931a) wrote that there were post- Hospital because of bouts of violent uncontrollable epileptic actions " of a kind which in a man fully behaviour and repeated attempts to abscond. He was himself would be criminal ". But another 25 years the seventh child of healthy working-class parents. were to elapse before Penfield began his studies on There is no family history of epilepsy. His birth was brain-scars (Penfield and Erickson, 1941) which were normal and he was breast fed for nine months. He guest. Protected by copyright. eventually to secure for surgery a began to walk and talk at about 14 months. As a child place in the be was placid but active, easily managed, and there were treatment of epilepsy. At first the operations were no difficulties in toilet training. restricted to those patients resistant to medical At the age of 7 years he fell out of a tree and was treatment in whom there was conclusive evidence of momentarily unconscious. -

The Value of Seizure Semiology in Lateralizing and Localizing Partially Originating Seizures

Review Article The value of seizure semiology in lateralizing and localizing partially originating seizures Mohammed M. Jan, MBChB, FRCP(C). observations help in lateralizing (left versus right) and ABSTRACT localizing (involved brain region) the seizure onset. Therefore, this information is vital not only for seizure Diagnosing epilepsy depends heavily on a detailed, and accurate description of the abnormal transient classification, but more so for identification of surgical neurological manifestations. Observing the candidates. The EEG and neuroimaging, particularly seizures yields important semiologic features that MRI, are needed to identify focal physiological and characterize epilepsy. Video-EEG monitoring allows pathological brain abnormalities.3-5 The development of the identification of important lateralizing (left video-EEG monitoring has allowed careful correlation of versus right), and localizing (involved brain region) semiologic features with simultaneous EEG recordings.6 semiologic features. This information is vital for As a result, clinical semiology gained greater reliability identifying the seizure origin for possible surgical in diagnosing specific seizure types and localizing their interventions. The aim of this review is to present a onset.7 The aim of this review is to present a summary summary of important semiologic characteristics of various seizures that are important for accurate seizure of important semiologic characteristics of various lateralization and localization. This would most seizures that are needed for accurate lateralization likely help during reviewing video-EEG recorded and localization. This would most likely help during seizures of intractable patients for possible epilepsy reviewing video-EEG recorded seizures of intractable surgery. Semiologic features of partial and secondarily patients for possible epilepsy surgery. generalized seizures can be grouped into one of 4 History taking. -

A Rare Case of Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome Development in an Immunocompromised Patient with Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy And

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Case Reports in Neurological Medicine Volume 2013, Article ID 460701, 5 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/460701 Case Report A Rare Case of Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome Development in an Immunocompromised Patient with Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy and Multicentric Castleman’s Disease Mohankumar Kurukumbi,1 Sheldon Steiner,1,2 Shariff Dunlap,1 Sherita Chapman,3 Noha Solieman,1 and Annapurni Jayam-Trouth1 1 Department of Neurology, Howard University Hospital, 2041 Georgia Avenue, Washington, DC 20060, USA 2 Department of Neurology, Howard University College of Medicine, Washington, DC 20060, USA 3 Department of Neurology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22908, USA Correspondence should be addressed to Mohankumar Kurukumbi; [email protected] Received 27 June 2013; Accepted 17 July 2013 AcademicEditors:T.K.Banerjee,J.L.Gonzalez-Guti´ errez,´ R. Hashimoto, J. C. Kattah, and Y. Wakabayashi Copyright © 2013 Mohankumar Kurukumbi et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) development in HIV with preexistent progressive multifocal leukoen- cephalopathy (PML) has been extensively studied. PML-IRIS typically manifests clinically as new or worsening neurologic symptoms in conjunction with enlarging CNS lesions and occurs in approximately 10–20 percent of HIV-infected patients with PML who begin HAART. Likewise, Multicentric Castleman’s Disease (MCD), a rare malignant lymphoproliferative disorder, has a strong and well-known association with HIV. Our case provides a rare instance of PML-IRIS in combination with MCD in an HIV-positive individual. -

Epilepsy Syndromes E9 (1)

EPILEPSY SYNDROMES E9 (1) Epilepsy Syndromes Last updated: September 9, 2021 CLASSIFICATION .......................................................................................................................................... 2 LOCALIZATION-RELATED (FOCAL) EPILEPSY SYNDROMES ........................................................................ 3 TEMPORAL LOBE EPILEPSY (TLE) ............................................................................................................... 3 Epidemiology ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Etiology, Pathology ................................................................................................................................ 3 Clinical Features ..................................................................................................................................... 7 Diagnosis ................................................................................................................................................ 8 Treatment ............................................................................................................................................. 15 EXTRATEMPORAL NEOCORTICAL EPILEPSY ............................................................................................... 16 Etiology ................................................................................................................................................ 16 -

Seizure, New Onset

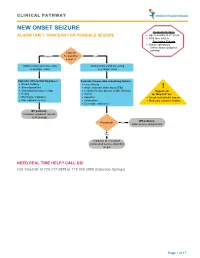

CLINICAL PATHWAY NEW ONSET SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria ALGORITHM 1. CONCERN FOR POSSIBLE SEIZURE • Age 6 months to 21 years • First-time seizure Exclusion Criteria • Status epilepticus (refer to status epilepticus pathway) Concern Unsure for possible Yes seizure? Obtain history and screening Obtain history and screening neurologic exam neurologic exam Consider differential diagnoses: Evaluate for possible provoking factors: • Breath holding • Fever/illness • Stereotypies/tics • Acute traumatic brain injury (TBI) ! • Vasovagal/syncope/vertigo • Central nervous system (CNS) infection Urgent call • Reflux • Tumor to ‘OneCall’ for: • Electrolyte imbalance • Ingestion • Suspected infantile spasm • Non epileptic seizure • Intoxication • Medically complex children • Electrolyte imbalance Off pathway: Consider outpatient referral to Neurology Off pathway: Provoked? Yes Address provoking factors No Continue to new onset unprovoked seizure algorithm on p.2 NEED REAL TIME HELP? CALL US! Call ‘OneCall’ at 720-777-3999 or 719-305-3999 (Colorado Springs) Page 1 of 17 CLINICAL PATHWAY ALGORITHM 2. NEW ONSET UNPROVOKED SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria • Age 6 months to 21 years New onset unprovoked • First-time unprovoked seizure seizure • Newly recognized seizure or epilepsy syndrome Exclusion Criteria • Provoked seizure: any seizure as a symptom of fever/illness, acute traumatic brain injury (TBI), Has central nervous system (CNS) infection, tumor, patient returned ingestion, intoxication, or electrolyte imbalance Consult inpatient • to baseline within No -

Epilepsy After Stroke

Stroke Helpline: 0303 3033 100 Website: stroke.org.uk Epilepsy after stroke In the first few weeks after a stroke some people have a seizure, and a small number go on to develop epilepsy – a tendency to have repeated seizures. These can usually be completely controlled with treatment. This factsheet explains what epilepsy is, the different types of seizures, and how epilepsy is diagnosed and treated. It also includes advice about coping with a seizure, and a glossary. Epilepsy is a tendency to have repeated What causes seizures? seizures – sometimes called ‘fits’ or ‘attacks’. It affects just under one per cent Cells in the brain communicate with one of people in the UK. Stroke is one of many another and with our muscles by passing conditions that can lead to epilepsy. electrical signals along nerve fibres. If you have epilepsy this electrical activity can Around five per cent of people who have a become disordered. A sudden abnormal stroke will have a seizure within the following burst of electrical activity in the brain can few weeks. These are known as acute or lead to a seizure. onset seizures and normally happen within 24 hours of the stroke. You are more likely There are over 40 different types of seizures to have one if you have had a severe stroke, ranging from tingling sensations or ‘going a stroke caused by bleeding in the brain (a blank’ for a few seconds, to shaking and haemorrhagic stroke), or a stroke involving losing consciousness. the part of the brain called the cerebral cortex. If you have an onset seizure, it This can mean that epilepsy is sometimes does not necessarily mean you have or will confused with other conditions, including develop epilepsy. -

Dictionary of Epilepsy

DICTIONARY OF EPILEPSY PART I: DEFINITIONS .· DICTIONARY OF EPILEPSY PART I: DEFINITIONS PROFESSOR H. GASTAUT President, University of Aix-Marseilles, France in collaboration with an international group of experts ~ WORLD HEALTH- ORGANIZATION GENEVA 1973 ©World Health Organization 1973 Publications of the World Health Organization enjoy copyright protection in accord ance with the provisions of Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. For rights of reproduction or translation of WHO publications, in part or in toto, application should be made to the Office of Publications and Translation, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. The World Health Organization welcomes such applications. PRINTED IN SWITZERLAND WHO WORKING GROUP ON THE DICTIONARY OF EPILEPSY1 Professor R. J. Broughton, Montreal Neurological Institute, Canada Professor H. Collomb, Neuropsychiatric Clinic, University of Dakar, Senegal Professor H. Gastaut, Dean, Joint Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, University of Aix-Marseilles, France Professor G. Glaser, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn., USA Professor M. Gozzano, Director, Neuropsychiatric Clinic, Rome, Italy Dr A. M. Lorentz de Haas, Epilepsy Centre "Meer en Bosch", Heemstede, Netherlands Professor P. Juhasz, Rector, University of Medical Science, Debrecen, Hungary Professor A. Jus, Chairman, Psychiatric Department, Academy of Medicine, Warsaw, Poland Professor A. Kreindler, Institute of Neurology, Academy of the People's Republic of Romania, Bucharest, Romania Dr J. Kugler, Department of Psychiatry, University of Munich, Federal Republic of Germany Dr H. Landolt, Medical Director, Swiss Institute for Epileptics, Zurich, Switzerland Dr B. A. Lebedev, Chief, Mental Health, WHO, Geneva, Switzerland Dr R. L. Masland, Department of Neurology, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York, USA Professor F. -

Supplementary Table Term* Revised Term** Focal Seizure Without Impairment of a Subjective Sensory Or Psychic Experience As Part of Migraine Or Epilepsy

Supplementary table Term* Revised term** Focal seizure without impairment of A subjective sensory or psychic experience as part of migraine or epilepsy. In epilepsy it is a focal consciousness or awareness Aura seizure without loss of consciousness (a simple partial seizure). It may or may not be followed by involving subjective sensory or other seizure manifestations. psychic phenomena only Automatic behaviour associated with loss of awareness, such as lip smacking or hand wringing, Automatism Focal dyscognitive seizure occurring as part of a complex partial seizure. Convulsion (previously "grand Tonic-clonic seziure, convulsive Seizure with involuntary, irregular myoclonic, clonic or tonic–clonic movements of one or more mal") seizure limbs. Onset may be focal or primary generalised. Literally ‘already seen’, this refers to a false impression that a present experience is familiar. It is used to refer to something heard, experienced or seen. It can be the aura of a temporal lobe Déjà vu seizure, but also happens in other settings (normal experience, intoxication, migraine, psychiatric). Focal seizure (previously "partial, Focal seizure A seizure originating in a specific cortical location. May be due to a structural lesion. localization related") Literally a ‘blow’. Usually used for an epileptic seizure (but can refer to other paroxysmal events, Ictus such as migraine, transient neurological events and stroke). Similarly pre- and post-ictal are used may for the period before and after a seizure. Idiopathic Genetic In relation to epilepsy, this implies that there is an underlying genetic cause. Literally ‘never seen’, this refers to a false impression that a present experience is unfamiliar. It is Jamais vu used for something seen, heard or experienced. -

Multimodal Longitudinal Imaging of Focal Status Epilepticus

CASE REPORT Multimodal Longitudinal Imaging of Focal Status Epilepticus Colin P. Doherty, Andrew J. Cole, P. Ellen Grant, Alan Fischman, Elizabeth Dooling, Daniel B. Hoch, Tessa Hedley White, G. Rees Cosgrove ABSTRACT: Background: Little is understood about the evolution of structural and functional brain changes during the course of uncontrolled focal status epilepticus in humans. Methods: We serially evaluated and treated a nine-year-old girl with refractory focal status epilepticus. Long-term EEG monitoring, MRI, MRA, SPECT, intraoperative visualization of affected cortex, and neuropathological examination of a biopsy specimen were conducted over a three year time span. Imaging changes were correlated with simultaneous treatment and EEG findings. Results: The EEG monitoring showed almost continuous spike discharges emanating initially from the right frontocentral area. These EEG abnormalities were intermittently suppressed by treatment with anesthetics. Over time, additional brain areas developed epileptiform EEG abnormalities. Serial MRI studies demonstrated an evolution of changes from normal, through increased regional T2 signal to generalized atrophy. An MRAdemonstrated dilatation of the middle cerebral artery stem on the right compared to the left with a broad distribution of flow-related enhancement. An 18FDG-PET scan showed a dramatically abnormal metabolic profile in the same right frontocentral areas, which modulated in response to treatment during the course of the illness. A right frontotemporal craniotomy revealed a markedly hyperemic cortical focus including vascular shunting. A sample of resected cortex showed severe gliosis and neuronal death. Conclusions: The co-registration of structural and functional imaging and its correlation with operative and pathological findings in this case illustrates the relentless progression of regional and generalized abnormalities in intractable focal status epilepticus that were only transiently modified by exhaustive therapeutic interventions. -

Epileptic Psychosis and Insanity: Case Study and Review PATRICK D

Epileptic Psychosis and Insanity: Case Study and Review PATRICK D. BACON, MD ELISSA P. BENEDEK, MD This brief clinical report focuses on a case in which we were ordered by the Wayne County Circuit Court to complete a forensic evaluation of a 26- year-old man facing criminal charges of Felonious Assault and Criminal Sexual Conduct. The patient believed that he had committed the offenses but that his behavior was substantially influenced by a recently diagnosed seizure disorder. After a complete clinical exam, the forensic examiners (Patrick Bacon, MD and Elissa Benedek, MD) reported to the court the defendant was psychotic at the time of the alleged offense and this psychosis was associated with his epileptic disorder but did not represent an epileptic automatism. In the past century, many epileptics charged with a crime have defended themselves by arguing that their alleged criminal behavior was the result of an epileptic automatism. Investigators have delineated research criteria to evaluate the question of whether the behavior of these individuals could have been the result of an automatism.l.2,:l To our knowledge, no epileptic has argued he or she was legally insane at the time ofthe alleged offense and his or her insanity was due to a psychotic episode that occurred as a· concomitant of his or her epileptic disorder. Psychotic episodes that occur in association with various epileptic disorders have been reported by sev eral investigators. 4,5 The characteristics of these psychotic episodes are significantly different from the characteristics of epileptic automatisms. We review the patient we evaluated and discuss the characteristics of au tomatisms and epileptic psychoses that allow each to be recognized as a distinct clinical entity.