Relation of Photosensitivity to Epileptic Syndromes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway

JOHNS HOPKINS ALL CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway 1 Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway Table of Contents 1. Rationale 2. Background 3. Diagnosis 4. Labs 5. Radiologic Studies 6. General Management 7. Status Epilepticus Pathway 8. Pharmacologic Management 9. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring 10. Inpatient Status Admission Criteria a. Admission Pathway 11. Outcome Measures 12. References Last updated: July 7, 2019 Owners: Danielle Hirsch, MD, Emergency Medicine; Jennifer Avallone, DO, Neurology This pathway is intended as a guide for physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners and other healthcare providers. It should be adapted to the care of specific patient based on the patient’s individualized circumstances and the practitioner’s professional judgment. 2 Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway Rationale This clinical pathway was developed by a consensus group of JHACH neurologists/epileptologists, emergency physicians, advanced practice providers, hospitalists, intensivists, nurses, and pharmacists to standardize the management of children treated for status epilepticus. The following clinical issues are addressed: ● When to evaluate for status epilepticus ● When to consider admission for further evaluation and treatment of status epilepticus ● When to consult Neurology, Hospitalists, or Critical Care Team for further management of status epilepticus ● When to obtain further neuroimaging for status epilepticus ● What ongoing therapy patients should receive for status epilepticus Background: Status epilepticus (SE) is the most common neurological emergency in children1 and has the potential to cause substantial morbidity and mortality. Incidence among children ranges from 17 to 23 per 100,000 annually.2 Prevalence is highest in pediatric patients from zero to four years of age.3 Ng3 acknowledges the most current definition of SE as a continuous seizure lasting more than five minutes or two or more distinct seizures without regaining awareness in between. -

Cognitive Impairment: Causes, Diagnosis and Treatment

NEUROLOGY - LABORATORY AND CLINICAL RESEARCH DEVELOPMENTS COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT: CAUSES, DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT No part of this digital document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means. The publisher has taken reasonable care in the preparation of this digital document, but makes no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assumes no responsibility for any errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of information contained herein. This digital document is sold with the clear understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, medical or any other professional services. NEUROLOGY – LABORATORY AND CLINICAL RESEARCH DEVELOPMENTS SERIES Intracranial Hypertension Stefan Mircea Iencean and Alexandru Vladimir Ciurea 2009 ISBN: 978-1-60741-862-7 (Hardcover Book) Intracranial Hypertension Stefan Mircea Iencean and Alexandru Vladimir Ciurea 2009 ISBN: 978-1-60876-549-2 (Online Book) Cerebral Blood Flow Regulation Nodar P. Mitagvaria and Haim (James) I. Bicher 2009 ISBN: 978-1-60692-163-0 Cerebral Ischemia in Young Adults: Pathogenic and Clinical Perspectives Alessandro Pezzini and Alessandro Padovani (Editors) 2009 ISBN: 978-1-60741-627-2 Dizziness: Vertigo, Disequilibrium and Lightheadedness Agnes Lindqvist and Gjord Nyman (Editors) 2009: ISBN 978-1-60741-847-4 Somatosensory Cortex: Roles, Interventions and Traumas Niels Johnsen and Rolf Agerskov (Editors) 2009. ISBN: 978-1-60741-876-4 Cognitive Impairment: Causes, Diagnosis and Treatment Melanie L. Landow (Editor) 2009. ISBN: 978-1-60876-205-7 NEUROLOGY - LABORATORY AND CLINICAL RESEARCH DEVELOPMENTS COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT: CAUSES, DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT MELANIE L. -

A Small Number of People Have What Is Known As Reflex Epilepsy, In

A small number of people have what is known What are the features of reflex epilepsy? as reflex epilepsy, in which seizures are set off There are many different types of reflex by specific stimuli. These can include flashing epilepsy, depending on the area of the brain that lights, a flickering computer “monitor”, sudden is affected. Seizure stimuli may be very specific, noises, a particular piece of music, or the phone or they may be broad categories. They can ringing. Some people even have seizures when include: they think about a particular subject or see their own hand! flashing or flickering lights, including computer monitors or video games. This is What are other terms for reflex epilepsy? called photosensitive epilepsy. It is the most Other terms for reflex epilepsy that you may common childhood form of reflex epilepsy, come across include: and the child may eventually outgrow it. the sight of a particular pattern; this is called epilepsy with reflex seizures visual pattern reflex epilepsy sensory precipitation epilepsy thinking about certain things stimulus sensitive epilepsy performing a certain task, such as typing; this is called praxis-induced epilepsy There are also many terms for specific types of reading reflex epilepsy. language-related stimuli such as writing, listening to speech, singing, or reciting What causes reflex epilepsy? certain passages of music; this is called The seizure stimulus is not the underlying cause musicogenic epilepsy of the epilepsy. Rather, it sends a particular certain sounds; this is called audiogenic message to a sensitive, seizure-prone area of the epilepsy brain, excites the neurons there, and causes a surprises or startles seizure. -

Photosensitive Epilepsy

photosensitive epilepsy factsheet If you have epilepsy you may be able to identify triggers – situations that set off your seizures. Common triggers include stress or tiredness. If seizures are triggered by flashing lights 1 or certain patterns, this is called photosensitive epilepsy. how common is photosensitive epilepsy? how is photosensitive epilepsy treated? Around 1 in 100 people has epilepsy, and of these Photosensitive epilepsy usually responds well to people, around 3% have photosensitive epilepsy. anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) that treat generalised Photosensitive epilepsy is more common in children seizures (seizures that affect both sides of the brain and young people (up to 5%) and is less commonly at once). diagnosed after the age of 20. See our booklet and chart medication for epilepsy for more information. how can I tell if I am photosensitive? Many people know this if they have a seizure Triggers are individual, but the following sources when they are exposed to flashing lights or patterns in themselves are not generally likely to trigger as a photosensitive trigger will usually cause photosensitive seizures. See over the page for a seizure straightaway. possible triggers and what increases the risk. An electroencephalogram (EEG) may include testing • UK TV programme content. Ofcom regulates for photosensitive epilepsy. This involves looking at a material shown on TV in the UK. The regulations light which will flash at different speeds. If this causes restrict the flash rate to three hertz or less, and any changes in brain activity the technician can stop they also restrict the area of screen allowed for the flashing light before a seizure develops. -

A Rare Case of Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome Development in an Immunocompromised Patient with Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy And

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Case Reports in Neurological Medicine Volume 2013, Article ID 460701, 5 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/460701 Case Report A Rare Case of Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome Development in an Immunocompromised Patient with Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy and Multicentric Castleman’s Disease Mohankumar Kurukumbi,1 Sheldon Steiner,1,2 Shariff Dunlap,1 Sherita Chapman,3 Noha Solieman,1 and Annapurni Jayam-Trouth1 1 Department of Neurology, Howard University Hospital, 2041 Georgia Avenue, Washington, DC 20060, USA 2 Department of Neurology, Howard University College of Medicine, Washington, DC 20060, USA 3 Department of Neurology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22908, USA Correspondence should be addressed to Mohankumar Kurukumbi; [email protected] Received 27 June 2013; Accepted 17 July 2013 AcademicEditors:T.K.Banerjee,J.L.Gonzalez-Guti´ errez,´ R. Hashimoto, J. C. Kattah, and Y. Wakabayashi Copyright © 2013 Mohankumar Kurukumbi et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) development in HIV with preexistent progressive multifocal leukoen- cephalopathy (PML) has been extensively studied. PML-IRIS typically manifests clinically as new or worsening neurologic symptoms in conjunction with enlarging CNS lesions and occurs in approximately 10–20 percent of HIV-infected patients with PML who begin HAART. Likewise, Multicentric Castleman’s Disease (MCD), a rare malignant lymphoproliferative disorder, has a strong and well-known association with HIV. Our case provides a rare instance of PML-IRIS in combination with MCD in an HIV-positive individual. -

Epilepsy Syndromes E9 (1)

EPILEPSY SYNDROMES E9 (1) Epilepsy Syndromes Last updated: September 9, 2021 CLASSIFICATION .......................................................................................................................................... 2 LOCALIZATION-RELATED (FOCAL) EPILEPSY SYNDROMES ........................................................................ 3 TEMPORAL LOBE EPILEPSY (TLE) ............................................................................................................... 3 Epidemiology ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Etiology, Pathology ................................................................................................................................ 3 Clinical Features ..................................................................................................................................... 7 Diagnosis ................................................................................................................................................ 8 Treatment ............................................................................................................................................. 15 EXTRATEMPORAL NEOCORTICAL EPILEPSY ............................................................................................... 16 Etiology ................................................................................................................................................ 16 -

Seizure, New Onset

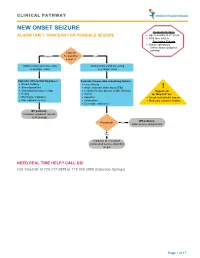

CLINICAL PATHWAY NEW ONSET SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria ALGORITHM 1. CONCERN FOR POSSIBLE SEIZURE • Age 6 months to 21 years • First-time seizure Exclusion Criteria • Status epilepticus (refer to status epilepticus pathway) Concern Unsure for possible Yes seizure? Obtain history and screening Obtain history and screening neurologic exam neurologic exam Consider differential diagnoses: Evaluate for possible provoking factors: • Breath holding • Fever/illness • Stereotypies/tics • Acute traumatic brain injury (TBI) ! • Vasovagal/syncope/vertigo • Central nervous system (CNS) infection Urgent call • Reflux • Tumor to ‘OneCall’ for: • Electrolyte imbalance • Ingestion • Suspected infantile spasm • Non epileptic seizure • Intoxication • Medically complex children • Electrolyte imbalance Off pathway: Consider outpatient referral to Neurology Off pathway: Provoked? Yes Address provoking factors No Continue to new onset unprovoked seizure algorithm on p.2 NEED REAL TIME HELP? CALL US! Call ‘OneCall’ at 720-777-3999 or 719-305-3999 (Colorado Springs) Page 1 of 17 CLINICAL PATHWAY ALGORITHM 2. NEW ONSET UNPROVOKED SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria • Age 6 months to 21 years New onset unprovoked • First-time unprovoked seizure seizure • Newly recognized seizure or epilepsy syndrome Exclusion Criteria • Provoked seizure: any seizure as a symptom of fever/illness, acute traumatic brain injury (TBI), Has central nervous system (CNS) infection, tumor, patient returned ingestion, intoxication, or electrolyte imbalance Consult inpatient • to baseline within No -

Lafora Disease: Molecular Etiology Lafora Hastalığı: Moleküler Etiyoloji S

Epilepsi 2018;24(1):1-7 DOI: 10.14744/epilepsi.2017.48278 REVIEW / DERLEME Lafora Disease: Molecular Etiology Lafora Hastalığı: Moleküler Etiyoloji S. Hande ÇAĞLAYAN1,2 1Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics, Boğaziçi University, İstanbul, Turkey S. Hande CAĞLAYAN, Ph.D. 2International Biomedicine and Genome Center, Dokuz Eylül University, İzmir, Turkey Summary Lafora Disease (LD) is a fatal neurodegenerative condition characterized by the accumulation of abnormal glycogen inclusions known as Lafora bodies (LBs). Patients with LD manifest myoclonus and tonic-clonic seizures, visual hallucinations, and progressive neurological deteri- oration beginning at the age of 8-18 years. Mutations in either EPM2A gene encoding protein phosphatase laforin or NHLRC1 gene encoding ubiquitin-ligase malin cause LD. Approximately, 200 distinct mutations accounting for the disease are listed in the Lafora progressive my- oclonus epilepsy mutation and polymorphism database. In this review, the genotype-phenotype correlations, the genetic diagnosis of LD, the downregulation of glycogen metabolism as the main cause of LD pathogenesis and the regulation of glycogen synthesis as a key target for the treatment of LD are discussed. Key words: EPM2A and NHLRC1 gene mutations; genotype-phenotype relationship; Lafora progressive myoclonus epilepsy; LD pathogenesis. Özet Lafora hastalığı (LD) Lafora cisimleri (LB) olarak bilinen anormal glikojen yapıların birikmesi ile karakterize olan ölümcül bir nörodejeneratif hastalıktır. Lafora hastalarında 8–18 yaş arası başlayan miyoklonik ve tonik-klonik nöbetler, halüsinasyonlar ve ilerleyen nörolojik bozulma görülür. Lafora hastalığı protein fosfataz laforini kodlayan EPM2A geni veya ubikitin ligaz malini kodlayan NHLRC1 geni mutasyonları ile orta- ya çıkar. Hastalığa sebep olan yaklaşık 200 farklı mutasyon “Lafora Progressive Myoclonus Epilepsy Mutation and Polymorphism Database” de listelenmiştir. -

Valproate in Adolescents with Photosensitive Epilepsy with Generalized Tonic-Clonic Seizures Only

european journal of paediatric neurology 18 (2014) 13e18 Official Journal of the European Paediatric Neurology Society Original article Valproate in adolescents with photosensitive epilepsy with generalized toniceclonic seizures only Alberto Verrotti a,g, Salvatore Grosso b, Claudia D’Egidio a, Pasquale Parisi c, Alberto Spalice d, Piero Pavone e, Giuseppe Capovilla f, Sergio Agostinelli a,* a Department of Pediatrics, University of Chieti, Via dei Vestini 5, 66100 Chieti, Italy b Department of Pediatrics, University of Siena, Siena, Italy c Chair of Pediatrics, II Faculty of Medicine, “La Sapienza” University of Rome, Rome, Italy d Department of Pediatrics, I Faculty of Medicine, “La Sapienza” University of Rome, Rome, Italy e Division of Pediatric Neurology, University of Catania, Catania, Italy f Epilepsy Center, Department of Child Neuropsychiatry, C. Poma Hospital, Mantova, Italy g Department of Pediatrics, University of Perugia, Perugia, Italy article info abstract Article history: Aim: To assess the effects of valproate (VPA) on seizure response/control and photo- Received 17 December 2012 sensitivity (PS) in adolescents suffering from photosensitive epilepsy with generalized Received in revised form toniceclonic seizures only (EGTCS). 8 April 2013 Methods: We prospectively evaluated 55 adolescents with newly diagnosed EGTCS and PS at Accepted 29 June 2013 presentation, who received VPA monotherapy. Two phases of the study were defined and analysed separately. In the phase I, the electroclinical data of patients were compared over Keywords: three time points: T1 (at 6 months of treatment); T2 (at 12 months of treatment); and T3 (at Adolescents 36 months of treatment). In the phase II, only patients who stopped VPA were evaluated Valproate over a period of 12 months. -

ILAE Classification and Definition of Epilepsy Syndromes with Onset in Childhood: Position Paper by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions

ILAE Classification and Definition of Epilepsy Syndromes with Onset in Childhood: Position Paper by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions N Specchio1, EC Wirrell2*, IE Scheffer3, R Nabbout4, K Riney5, P Samia6, SM Zuberi7, JM Wilmshurst8, E Yozawitz9, R Pressler10, E Hirsch11, S Wiebe12, JH Cross13, P Tinuper14, S Auvin15 1. Rare and Complex Epilepsy Unit, Department of Neuroscience, Bambino Gesu’ Children’s Hospital, IRCCS, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Rome, Italy 2. Divisions of Child and Adolescent Neurology and Epilepsy, Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester MN, USA. 3. University of Melbourne, Austin Health and Royal Children’s Hospital, Florey Institute, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia. 4. Reference Centre for Rare Epilepsies, Department of Pediatric Neurology, Necker–Enfants Malades Hospital, APHP, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Institut Imagine, INSERM, UMR 1163, Université de Paris, Paris, France. 5. Neurosciences Unit, Queensland Children's Hospital, South Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. Faculty of Medicine, University of Queensland, Queensland, Australia. 6. Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Aga Khan University, East Africa. 7. Paediatric Neurosciences Research Group, Royal Hospital for Children & Institute of Health & Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, Member of European Refence Network EpiCARE, Glasgow, UK. 8. Department of Paediatric Neurology, Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital, Neuroscience Institute, University of Cape Town, South Africa. 9. Isabelle Rapin Division of Child Neurology of the Saul R Korey Department of Neurology, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY USA. 10. Programme of Developmental Neurosciences, UCL NIHR BRC Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, Department of Clinical Neurophysiology, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, London, UK 11. -

Epilepsy After Stroke

Stroke Helpline: 0303 3033 100 Website: stroke.org.uk Epilepsy after stroke In the first few weeks after a stroke some people have a seizure, and a small number go on to develop epilepsy – a tendency to have repeated seizures. These can usually be completely controlled with treatment. This factsheet explains what epilepsy is, the different types of seizures, and how epilepsy is diagnosed and treated. It also includes advice about coping with a seizure, and a glossary. Epilepsy is a tendency to have repeated What causes seizures? seizures – sometimes called ‘fits’ or ‘attacks’. It affects just under one per cent Cells in the brain communicate with one of people in the UK. Stroke is one of many another and with our muscles by passing conditions that can lead to epilepsy. electrical signals along nerve fibres. If you have epilepsy this electrical activity can Around five per cent of people who have a become disordered. A sudden abnormal stroke will have a seizure within the following burst of electrical activity in the brain can few weeks. These are known as acute or lead to a seizure. onset seizures and normally happen within 24 hours of the stroke. You are more likely There are over 40 different types of seizures to have one if you have had a severe stroke, ranging from tingling sensations or ‘going a stroke caused by bleeding in the brain (a blank’ for a few seconds, to shaking and haemorrhagic stroke), or a stroke involving losing consciousness. the part of the brain called the cerebral cortex. If you have an onset seizure, it This can mean that epilepsy is sometimes does not necessarily mean you have or will confused with other conditions, including develop epilepsy. -

Supplementary Table Term* Revised Term** Focal Seizure Without Impairment of a Subjective Sensory Or Psychic Experience As Part of Migraine Or Epilepsy

Supplementary table Term* Revised term** Focal seizure without impairment of A subjective sensory or psychic experience as part of migraine or epilepsy. In epilepsy it is a focal consciousness or awareness Aura seizure without loss of consciousness (a simple partial seizure). It may or may not be followed by involving subjective sensory or other seizure manifestations. psychic phenomena only Automatic behaviour associated with loss of awareness, such as lip smacking or hand wringing, Automatism Focal dyscognitive seizure occurring as part of a complex partial seizure. Convulsion (previously "grand Tonic-clonic seziure, convulsive Seizure with involuntary, irregular myoclonic, clonic or tonic–clonic movements of one or more mal") seizure limbs. Onset may be focal or primary generalised. Literally ‘already seen’, this refers to a false impression that a present experience is familiar. It is used to refer to something heard, experienced or seen. It can be the aura of a temporal lobe Déjà vu seizure, but also happens in other settings (normal experience, intoxication, migraine, psychiatric). Focal seizure (previously "partial, Focal seizure A seizure originating in a specific cortical location. May be due to a structural lesion. localization related") Literally a ‘blow’. Usually used for an epileptic seizure (but can refer to other paroxysmal events, Ictus such as migraine, transient neurological events and stroke). Similarly pre- and post-ictal are used may for the period before and after a seizure. Idiopathic Genetic In relation to epilepsy, this implies that there is an underlying genetic cause. Literally ‘never seen’, this refers to a false impression that a present experience is unfamiliar. It is Jamais vu used for something seen, heard or experienced.