Epileptic Syndromes in Childhood. a Practical Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Use Anti-Epileptic Drugs Wisely ?

When to start and how to select antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) Dr. Chusak Limotai, MD., M.Sc., CSCN(C) Talk overview • When to start treatment ? • Which drug ? • Monotherapy • Combining AEDs (Rational polytherapy) • Old AEDs versus new AEDs • Drug level monitoring • When to discontinue AEDs ? When to start treatment ? • Correct diagnosis • Generally start after the second unprovoked seizure – First unprovoked seizure: A seizure or flurry of seizures or occurring within 24 hrs in the person > 1 month old of age – Epilepsy: 2 or more epileptic seizures occur unprovoked by any immediately identifiable cause ILAE 2014 • A person is considered to have epilepsy if they meet any of the following conditions. 1) At least two unprovoked (or reflex) seizures occurring greater than 24 hours apart. 2) One unprovoked (or reflex) seizure and a probability of further seizures similar to the general recurrence risk (at least 60%) after two unprovoked seizures, occurring over the next 10 years. 3) Diagnosis of an epilepsy syndrome – Epilepsy is considered to be resolved for individuals who had an age- dependent epilepsy syndrome but are now past the applicable age or those who have remained seizure-free for the last 10 years, with no seizure medicines for the last 5 years. Fisher RS et al. A practical clinical definition of epilepsy, Epilepsia 2014; 55:475-482 Cumulative risk of recurrence after a first unprovoked seizure 67% at 1 yr 78% at 3 yrs 44 % at 3 yrs 60% at 6 mo 32% at 3 yrs 17% at 3 yrs Hart YM et.al; The Lancet 1990 Indications to consider antiepileptic drug treatment after the first seizure Pohlmann-Eden B et.al BMJ 2006 Seneviratne U Postgrad Med J 2009 Factors associated with increased/lower risk • Increased risk: • Lower risk: – Adolescence onset – seizure occurred within – associated neurological 3 mo after acute insult deficits e.g. -

A Small Number of People Have What Is Known As Reflex Epilepsy, In

A small number of people have what is known What are the features of reflex epilepsy? as reflex epilepsy, in which seizures are set off There are many different types of reflex by specific stimuli. These can include flashing epilepsy, depending on the area of the brain that lights, a flickering computer “monitor”, sudden is affected. Seizure stimuli may be very specific, noises, a particular piece of music, or the phone or they may be broad categories. They can ringing. Some people even have seizures when include: they think about a particular subject or see their own hand! flashing or flickering lights, including computer monitors or video games. This is What are other terms for reflex epilepsy? called photosensitive epilepsy. It is the most Other terms for reflex epilepsy that you may common childhood form of reflex epilepsy, come across include: and the child may eventually outgrow it. the sight of a particular pattern; this is called epilepsy with reflex seizures visual pattern reflex epilepsy sensory precipitation epilepsy thinking about certain things stimulus sensitive epilepsy performing a certain task, such as typing; this is called praxis-induced epilepsy There are also many terms for specific types of reading reflex epilepsy. language-related stimuli such as writing, listening to speech, singing, or reciting What causes reflex epilepsy? certain passages of music; this is called The seizure stimulus is not the underlying cause musicogenic epilepsy of the epilepsy. Rather, it sends a particular certain sounds; this is called audiogenic message to a sensitive, seizure-prone area of the epilepsy brain, excites the neurons there, and causes a surprises or startles seizure. -

Photosensitive Epilepsy

photosensitive epilepsy factsheet If you have epilepsy you may be able to identify triggers – situations that set off your seizures. Common triggers include stress or tiredness. If seizures are triggered by flashing lights 1 or certain patterns, this is called photosensitive epilepsy. how common is photosensitive epilepsy? how is photosensitive epilepsy treated? Around 1 in 100 people has epilepsy, and of these Photosensitive epilepsy usually responds well to people, around 3% have photosensitive epilepsy. anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) that treat generalised Photosensitive epilepsy is more common in children seizures (seizures that affect both sides of the brain and young people (up to 5%) and is less commonly at once). diagnosed after the age of 20. See our booklet and chart medication for epilepsy for more information. how can I tell if I am photosensitive? Many people know this if they have a seizure Triggers are individual, but the following sources when they are exposed to flashing lights or patterns in themselves are not generally likely to trigger as a photosensitive trigger will usually cause photosensitive seizures. See over the page for a seizure straightaway. possible triggers and what increases the risk. An electroencephalogram (EEG) may include testing • UK TV programme content. Ofcom regulates for photosensitive epilepsy. This involves looking at a material shown on TV in the UK. The regulations light which will flash at different speeds. If this causes restrict the flash rate to three hertz or less, and any changes in brain activity the technician can stop they also restrict the area of screen allowed for the flashing light before a seizure develops. -

Clinicians Using the Classification Will Identify a Seizure As Focal Or Generalized Onset If There Is About an 80% Confidence Level About the Type of Onset

GENERALIZED ONSET SEIZURES Generalized onset seizures are not characterized by level of awareness, because awareness is almost always impaired. Generalized tonic-clonic: Immediate loss of Generalized epileptic spasms: Brief seizures with awareness, with stiffening of all limbs (tonic phase), flexion at the trunk and flexion or extension of the followed by sustained rhythmic jerking of limbs and limbs. Video-EEG recording may be required to face (clonic phase). Duration is typically 1 to 3 minutes. determine focal versus generalized onset. The seizure may produce a cry at the start, falling, tongue biting, and incontinence. Generalized typical absence: Sudden onset when activity stops with a brief pause and staring, Generalized clonic: Rhythmical sustained jerking of sometimes with eye fluttering and head nodding or limbs and/or head with no tonic stiffening phase. other automatic behaviors. If it lasts for more than These seizures most often occur in young children. several seconds, awareness and memory are impaired. Recovery is immediate. The EEG during these seizures Generalized tonic: Stiffening of all limbs, without always shows generalized spike-waves. clonic jerking. Generalized atypical absence: Like typical absence Generalized myoclonic: Irregular, unsustained jerking seizures, but may have slower onset and recovery and of limbs, face, eyes, or eyelids. The jerking of more pronounced changes in tone. Atypical absence generalized myoclonus may not always be left-right seizures can be difficult to distinguish from focal synchronous, but it occurs on both sides. impaired awareness seizures, but absence seizures usually recover more quickly and the EEG patterns are Generalized myoclonic-tonic-clonic: This seizure is like different. -

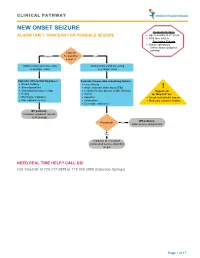

Seizure, New Onset

CLINICAL PATHWAY NEW ONSET SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria ALGORITHM 1. CONCERN FOR POSSIBLE SEIZURE • Age 6 months to 21 years • First-time seizure Exclusion Criteria • Status epilepticus (refer to status epilepticus pathway) Concern Unsure for possible Yes seizure? Obtain history and screening Obtain history and screening neurologic exam neurologic exam Consider differential diagnoses: Evaluate for possible provoking factors: • Breath holding • Fever/illness • Stereotypies/tics • Acute traumatic brain injury (TBI) ! • Vasovagal/syncope/vertigo • Central nervous system (CNS) infection Urgent call • Reflux • Tumor to ‘OneCall’ for: • Electrolyte imbalance • Ingestion • Suspected infantile spasm • Non epileptic seizure • Intoxication • Medically complex children • Electrolyte imbalance Off pathway: Consider outpatient referral to Neurology Off pathway: Provoked? Yes Address provoking factors No Continue to new onset unprovoked seizure algorithm on p.2 NEED REAL TIME HELP? CALL US! Call ‘OneCall’ at 720-777-3999 or 719-305-3999 (Colorado Springs) Page 1 of 17 CLINICAL PATHWAY ALGORITHM 2. NEW ONSET UNPROVOKED SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria • Age 6 months to 21 years New onset unprovoked • First-time unprovoked seizure seizure • Newly recognized seizure or epilepsy syndrome Exclusion Criteria • Provoked seizure: any seizure as a symptom of fever/illness, acute traumatic brain injury (TBI), Has central nervous system (CNS) infection, tumor, patient returned ingestion, intoxication, or electrolyte imbalance Consult inpatient • to baseline within No -

Genetics-Of-Epilepsy.Pdf

logy & N ro eu u r e o N p h f Bamikole, et al., J Neurol Neurophysiol 2019, 10:3 y o s l i o a n l o r g u y o J Journal of Neurology & Neurophysiology ISSN: 2155-9562 Review Open Access Genetics of Epilepsy Oluwayemi Joshua Bamikole *, Miles-Dei Benedict Olufeagba, Samuel Temitope Soge, Noah Olamide Bukoye, Taiwo Habeeb Olajide, Subulade Abigail Ademola, Olukemi Kehinde Amodu Institute of Child Health, University of Ibadan. Nigeria *Corresponding author: Oluwayemi Joshua Bamikole, Institute of Child Health, University of Ibadan, Nigeria, Tel: +2347068505498; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: February 06, 2019; Accepted date: March 27, 2019; Published date: August 09, 2019 Copyright: © 2019 Oluwayemi Joshua Bamikole. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Genetics is a branch of the human biology that provides insights into basic and vital processes which arise from birth till death, development to apoptosis (cell death), and in disease aetiology and therapies, or better methods in use of available treatments to solve human health conditions because genes function in all biological process. Epilepsy is a seizure that occurs without identifiable justification with a great chance of further seizures which is almost the same to the global recurrence risk of 60% after two unjustified seizures, happening over a ten years’ span. Fifty million people globally present with epilepsy ranging from about 20 to 70 cases per 100,000 in a year and Over 85% of the epilepsy cases are present in underdeveloped and even developing countries with low or middle income. -

Valproate in Adolescents with Photosensitive Epilepsy with Generalized Tonic-Clonic Seizures Only

european journal of paediatric neurology 18 (2014) 13e18 Official Journal of the European Paediatric Neurology Society Original article Valproate in adolescents with photosensitive epilepsy with generalized toniceclonic seizures only Alberto Verrotti a,g, Salvatore Grosso b, Claudia D’Egidio a, Pasquale Parisi c, Alberto Spalice d, Piero Pavone e, Giuseppe Capovilla f, Sergio Agostinelli a,* a Department of Pediatrics, University of Chieti, Via dei Vestini 5, 66100 Chieti, Italy b Department of Pediatrics, University of Siena, Siena, Italy c Chair of Pediatrics, II Faculty of Medicine, “La Sapienza” University of Rome, Rome, Italy d Department of Pediatrics, I Faculty of Medicine, “La Sapienza” University of Rome, Rome, Italy e Division of Pediatric Neurology, University of Catania, Catania, Italy f Epilepsy Center, Department of Child Neuropsychiatry, C. Poma Hospital, Mantova, Italy g Department of Pediatrics, University of Perugia, Perugia, Italy article info abstract Article history: Aim: To assess the effects of valproate (VPA) on seizure response/control and photo- Received 17 December 2012 sensitivity (PS) in adolescents suffering from photosensitive epilepsy with generalized Received in revised form toniceclonic seizures only (EGTCS). 8 April 2013 Methods: We prospectively evaluated 55 adolescents with newly diagnosed EGTCS and PS at Accepted 29 June 2013 presentation, who received VPA monotherapy. Two phases of the study were defined and analysed separately. In the phase I, the electroclinical data of patients were compared over Keywords: three time points: T1 (at 6 months of treatment); T2 (at 12 months of treatment); and T3 (at Adolescents 36 months of treatment). In the phase II, only patients who stopped VPA were evaluated Valproate over a period of 12 months. -

The Relationship Between the Components of Idiopathic Focal Epilepsy

Journal of Pediatrics and Neonatal Care Review Article Open Access The relationship between the components of idiopathic focal epilepsy Abstract Volume 8 Issue 3 - 2018 The classification of epileptic syndromes in children is not a simple duty, it requires Cesar Ramon Romero Leguizamon a great clinical ability as well as some degree of experience. Until today there is no Department of Drug Design and Pharmacology, University of international consensus regarding the different diseases that are part of the Idiopathic Copenhagen, Denmark Focal Epilepsies However, these diseases are the most prevalent in children suffering from some type of epilepsy, for this reason it is important to know more about these, Correspondence: Cesar Ramon Romero Leguizamon their clinical characteristics, pathological findings in studies such as encephalogram, M.D., Department of Drug Design and Pharmacology Faculty resonance, polysomnography and others. In the same way, to explore the possible of Health and Medical Science, University of Copenhagen, genetic origins of many of these pathologies, that have been little explored and Denmark, Jagtev 160, 2100 Copenhagen, Denmark, become an important therapeutic goal. A description of the most relevant aspects of Email [email protected] atypical benign partial epilepsy, Landau-Kleffner syndrome, benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes, electrical status epilepticus during sleep and Panayiotopoulos Received: February 17, 2018 | Published: May 14, 2018 syndrome is presented in this review, Allowing physicians and family members of children suffering from these diseases to have a better understanding and establish in this way a better diagnosis and treatment in patients, as well as promote in the scientific community the interest to investigate more about these relevant pathologies in childhood. -

ILAE Classification and Definition of Epilepsy Syndromes with Onset in Childhood: Position Paper by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions

ILAE Classification and Definition of Epilepsy Syndromes with Onset in Childhood: Position Paper by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions N Specchio1, EC Wirrell2*, IE Scheffer3, R Nabbout4, K Riney5, P Samia6, SM Zuberi7, JM Wilmshurst8, E Yozawitz9, R Pressler10, E Hirsch11, S Wiebe12, JH Cross13, P Tinuper14, S Auvin15 1. Rare and Complex Epilepsy Unit, Department of Neuroscience, Bambino Gesu’ Children’s Hospital, IRCCS, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Rome, Italy 2. Divisions of Child and Adolescent Neurology and Epilepsy, Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester MN, USA. 3. University of Melbourne, Austin Health and Royal Children’s Hospital, Florey Institute, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia. 4. Reference Centre for Rare Epilepsies, Department of Pediatric Neurology, Necker–Enfants Malades Hospital, APHP, Member of European Reference Network EpiCARE, Institut Imagine, INSERM, UMR 1163, Université de Paris, Paris, France. 5. Neurosciences Unit, Queensland Children's Hospital, South Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. Faculty of Medicine, University of Queensland, Queensland, Australia. 6. Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Aga Khan University, East Africa. 7. Paediatric Neurosciences Research Group, Royal Hospital for Children & Institute of Health & Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, Member of European Refence Network EpiCARE, Glasgow, UK. 8. Department of Paediatric Neurology, Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital, Neuroscience Institute, University of Cape Town, South Africa. 9. Isabelle Rapin Division of Child Neurology of the Saul R Korey Department of Neurology, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY USA. 10. Programme of Developmental Neurosciences, UCL NIHR BRC Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, Department of Clinical Neurophysiology, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, London, UK 11. -

Therapeutic Class Overview Anticonvulsants

Therapeutic Class Overview Anticonvulsants INTRODUCTION • Epilepsy is a disease of the brain defined by any of the following (Fisher et al 2014): At least 2 unprovoked (or reflex) seizures occurring > 24 hours apart; 1 unprovoked (or reflex) seizure and a probability of further seizures similar to the general recurrence risk (at least ○ 60%) after 2 unprovoked seizures, occurring over the next 10 years; ○ Diagnosis of an epilepsy syndrome. • Types of seizures include generalized seizures, focal (partial) seizures, and status epilepticus (Centers for Disease Control○ and Prevention [CDC] 2018, Epilepsy Foundation Greater Chicago 2020). Generalized seizures affect both sides of the brain and include: . Tonic-clonic (grand mal): begin with stiffening of the limbs, followed by jerking of the limbs and face ○ . Myoclonic: characterized by rapid, brief contractions of body muscles, usually on both sides of the body at the same time . Atonic: characterized by abrupt loss of muscle tone; they are also called drop attacks or akinetic seizures and can result in injury due to falls . Absence (petit mal): characterized by brief lapses of awareness, sometimes with staring, that begin and end abruptly; they are more common in children than adults and may be accompanied by brief myoclonic jerking of the eyelids or facial muscles, a loss of muscle tone, or automatisms. Focal seizures are located in just 1 area of the brain and include: . Simple: affect a small part of the brain; can affect movement, sensations, and emotion, without a loss of ○ consciousness . Complex: affect a larger area of the brain than simple focal seizures and the patient loses awareness; episodes typically begin with a blank stare, followed by chewing movements, picking at or fumbling with clothing, mumbling, and performing repeated unorganized movements or wandering; they may also be called “temporal lobe epilepsy” or “psychomotor epilepsy” . -

Mesial Frontal Epilepsy

Epikpsia, 39(Suppl. 4):S49-S61. 1998 Lippincon-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia 0 International League Against Epilepsy Mesial Frontal Epilepsy Norman K. So Oregon Comprehensive Epilepsy Program, Legacy Portland Hospitals, Portland, Oregon, U.S.A. Summary: The mesiofrontal cortex comprises a number of occur. The task of localization of the epileptogenic zone can be distinct anatomic and functional areas. Structural lesions and challenging, whether EEG or imaging methods are used. Suc- cortical dysgenesis are recognized causes of mesial frontal epi- cessful localization can lead to a rewarding outcome after epi- lepsy, but a specific gene defect may also be important, as seen lepsy surgery, particularly in those with an imaged lesion. in some forms of familial frontal lobe epilepsy. The predomi- Key Words: Mesial frontal epilepsy-cingulate gyrus- nant seizure manifestations, which are not necessarily strictly Supplementary motor area-Absence seizure-Hypermotor correlated with a specific ictal onset zone, are absence, hyper- seizure-Postural tonic seizure-Epilepsy surgery. motor, and postural tonic seizures. Other seizure types also FUNCTIONAL ANATOMY convolution. Traditional cytoarchitectonics have further subdivided this anterior frontal region. The frontal pole The frontal lobe is the largest lobe in the brain, ac- refers to the anterior most portion of the frontal lobe, but counting for one-third to one-half of total brain volume there is little consensus on how far back this extends. and weight. On the medial surface, the most important One or more curved.sulci are seen anterior and inferior to landmark is the cingulate sulcus (Fig. 1). This runs as an the cingulate sulcus, called the superior and inferior ros- inverted “C” following the contour of the corpus callo- tral sulci. -

The Double Generalization Phenomenon in Juvenile Absence Epilepsy

Epilepsy & Behavior 21 (2011) 318–320 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Epilepsy & Behavior journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/yebeh Case Report The double generalization phenomenon in juvenile absence epilepsy Daniel San-Juan a,b,⁎, Adriana Patricia M. Mayorga a, David J. Anschel c, Alvaro Moreno Avellán a, Maricarmen F. González-Aragón a, Andrew J. Cole d a Clinical Neurophysiology Department, National Institute of Neurology, Mexico City, Mexico b Centro Neurológico, Hospital ABC Santa Fe, Mexico City, Mexico c Clinical Neurophysiology Department, Saint Charles Hospital, Port Jefferson, NY, USA d Epilepsy Service, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA article info abstract Article history: The characterization of a seizure as generalized or focal onset depends on a basic knowledge of the underlying Received 12 March 2011 pathophysiology. Recently, an uncommon phenomenon in generalized epilepsy—evolution of seizures Revised 7 April 2011 from generalized to focal followed by secondary generalization—was reported for the first time. We describe a Accepted 8 April 2011 15-year-old boy, initially classified as having partial epilepsy, who had a typical absence seizure that became Available online 14 May 2011 focal with second secondary generalization (double generalization). On the basis of these findings his epilepsy fi Keywords: was classi ed as juvenile absence epilepsy and his treatment was changed, resulting in seizure freedom. This fi Juvenile absence epilepsy is the rst report of this unusual electroclinical evolution in a patient with juvenile absence epilepsy. The Generalized epilepsy recognition of this particular pattern allows correct classification and impacts both treatment and prognosis. Focal findings © 2011 Elsevier Inc.