JAHRBUCH DER GEOLOGISCHEN BUNDESANSTALT Jb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

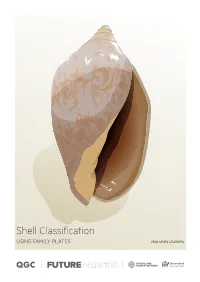

Shell Classification – Using Family Plates

Shell Classification USING FAMILY PLATES YEAR SEVEN STUDENTS Introduction In the following activity you and your class can use the same techniques as Queensland Museum The Queensland Museum Network has about scientists to classify organisms. 2.5 million biological specimens, and these items form the Biodiversity collections. Most specimens are from Activity: Identifying Queensland shells by family. Queensland’s terrestrial and marine provinces, but These 20 plates show common Queensland shells some are from adjacent Indo-Pacific regions. A smaller from 38 different families, and can be used for a range number of exotic species have also been acquired for of activities both in and outside the classroom. comparative purposes. The collection steadily grows Possible uses of this resource include: as our inventory of the region’s natural resources becomes more comprehensive. • students finding shells and identifying what family they belong to This collection helps scientists: • students determining what features shells in each • identify and name species family share • understand biodiversity in Australia and around • students comparing families to see how they differ. the world All shells shown on the following plates are from the • study evolution, connectivity and dispersal Queensland Museum Biodiversity Collection. throughout the Indo-Pacific • keep track of invasive and exotic species. Many of the scientists who work at the Museum specialise in taxonomy, the science of describing and naming species. In fact, Queensland Museum scientists -

Mollusks of Manuel Antonio National Park, Pacific Costa Rica

Rev. Biol. Trop. 49. Supl. 2: 25-36, 2001 www.rbt.ac.cr, www.ucr.ac.cr Mollusks of Manuel Antonio National Park, Pacific Costa Rica Samuel Willis 1 and Jorge Cortés 2-3 1140 East Middle Street, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania 17325, USA. 2Centro de Investigación en Ciencias del Mar y Limnología (CIMAR), Universidad de Costa Rica, 2060 San José, Costa Rica. FAX: (506) 207-3280. E-mail: [email protected] 3Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica, 2060 San José, Costa Rica. (Received 14-VII-2000. Corrected 23-III-2001. Accepted 11-V-2001) Abstract: The mollusks in Manuel Antonio National Park on the central section of the Pacific coast of Costa Rica were studied along thirty-six transects done perpendicular to the shore, and by random sampling of subtidal environments, beaches and mangrove forest. Seventy-four species of mollusks belonging to three classes and 40 families were found: 63 gastropods, 9 bivalves and 2 chitons, during this study in 1995. Of these, 16 species were found only as empty shells (11) or inhabited by hermit crabs (5). Forty-eight species were found at only one locality. Half the species were found at one site, Puerto Escondido. The most diverse habitat was the low rocky intertidal zone. Nodilittorina modesta was present in 34 transects and Nerita scabricosta in 30. Nodilittorina aspera had the highest density of mollusks in the transects. Only four transects did not clustered into the four main groups. The species composition of one cluster of transects is associated with a boulder substrate, while another cluster of transects associates with site. -

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS of the 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project March 2018 DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project Citation: Aguilar, R., García, S., Perry, A.L., Alvarez, H., Blanco, J., Bitar, G. 2018. 2016 Deep-sea Lebanon Expedition: Exploring Submarine Canyons. Oceana, Madrid. 94 p. DOI: 10.31230/osf.io/34cb9 Based on an official request from Lebanon’s Ministry of Environment back in 2013, Oceana has planned and carried out an expedition to survey Lebanese deep-sea canyons and escarpments. Cover: Cerianthus membranaceus © OCEANA All photos are © OCEANA Index 06 Introduction 11 Methods 16 Results 44 Areas 12 Rov surveys 16 Habitat types 44 Tarablus/Batroun 14 Infaunal surveys 16 Coralligenous habitat 44 Jounieh 14 Oceanographic and rhodolith/maërl 45 St. George beds measurements 46 Beirut 19 Sandy bottoms 15 Data analyses 46 Sayniq 15 Collaborations 20 Sandy-muddy bottoms 20 Rocky bottoms 22 Canyon heads 22 Bathyal muds 24 Species 27 Fishes 29 Crustaceans 30 Echinoderms 31 Cnidarians 36 Sponges 38 Molluscs 40 Bryozoans 40 Brachiopods 42 Tunicates 42 Annelids 42 Foraminifera 42 Algae | Deep sea Lebanon OCEANA 47 Human 50 Discussion and 68 Annex 1 85 Annex 2 impacts conclusions 68 Table A1. List of 85 Methodology for 47 Marine litter 51 Main expedition species identified assesing relative 49 Fisheries findings 84 Table A2. List conservation interest of 49 Other observations 52 Key community of threatened types and their species identified survey areas ecological importanc 84 Figure A1. -

COSSMANNIANA Bulletin Du Groupe D'étude Et De Recherche Macrofaune Cénozoïque

COSSMANNIANA Bulletin du Groupe d'Étude et de Recherche Macrofaune Cénozoïque Tome 3, numéro 4 Décembre 1995 ISSN 1157-4402 GROUPE D'ÉTUDE ET DE RECHERCHE MACROFAUNE CÉNOZOïQUE "Maisonpour tous" 26, rue Gérard Philippe 94120 FONTENAY-SOUS-SOIS Président . .. ... Jacques PONS Secrétaire .. PierreLOZOUET Trésorier . .. .. Philippe MAESTRATI Dessins de couverture : Jacques LERENARD Maquette et Édition: Jacques LERENARD [eau-Michel PACAUD Couverture: Campanile (Campanilopa) giganteum, d'après la figure 137-45 de l'tconographie (grossissement 3/8); et individu bréphiqu e (hauteur totale : 2 mm), muni de son périostracum et de sa protoconque (coll. LeRenard) . COSSMANNIANA, Paris, 3 (4), Décembre 1995, pp. 133-150, sans fig. ISSN: 1157-4402 . RÉVISION DES MOLLUSQUES PALÉOGÈNES DU BASSIN DE PARIS III - CHRONOLOGIE DES CRÉATEURS DE RÉFÉRENCES PRIMAIRES par Jacques ·LERENARD Laboratoire de Biologiedes Invertébrés Marins et Malacologie, Muséum.National d'Histoire Naturelle, 55,rue de Buffon- 75005 Paris - FRANCE RÉSUMÉ - La liste des 437 publications dans lesquelles ont été introduites des références primaires figurant dans la partie II (LERENARD & PACAUD, 1995, pp. 65-132) est donnée. Il s'agit de la première liste de l'ensemble des publications concernant des nouveaux noms ou des nouvelles espèces paléogènes de Mollusques du bassin de Paris. TITLE - Revision of the Paris Basin Paleogene MoIlusca. III: Chronological Iist of the authors of primary references. ABSTRACT - The 437 publications, in which the primary references cited in part II (LERENARD & PACAUD, 1995, pp. 65-132) have been introduced, are given. This constitutes the first list of aIl the publications that are conceming new species or new names of Paris Basin Paleogene Molluscan species. -

Synopsis of the Biological Data on the Loggerhead Sea Turtle Caretta Caretta (Linnaeus 1758)

BIOLOGICAL REPORT 88(14) MAY 1988 SYNOPSIS OF THE BIOLOGICAL DATA ON THE LOGGERHEAD SEA TURTLE CARETTA CARETTA (LINNAEUS 1758) Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Department of the Interior Biological Report This publication series of the Fish and Wildlife Service comprises reports on the results of research, developments in technology, and ecological surveys and inventories of effects of land-use changes on fishery and wildlife resources. They may include proceedings of workshops, technical conferences, or symposia; and interpretive bibliographies. They also include resource and wetland inventory maps. Copies of this publication may be obtained from the Publications Unit, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, DC 20240, or may be purchased from the National Technical Information Ser- vice (NTIS), 5285 Port Royal Road, Springfield, VA 22161. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dodd, C. Kenneth. Synopsis of the biological data on the loggerhead sea turtle. (Biological report ; 88(14) (May 1988)) Supt. of Docs. no. : I 49.89/2:88(14) Bibliography: p. 1. Loggerhead turtle. I. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 11. Title. 111. Series: Biological Report (Washington, D.C.) ; 88-14. QL666.C536D63 1988 597.92 88-600 12 1 This report may be cited as follows: Dodd, C. Kenneth, Jr. 1988. Synopsis of the biological data on the Loggerhead Sea Turtle Caretta caretta (Linnaeus 1758). U.S. Fish Wildl. Serv., Biol. Rep. 88(14). 110 pp. Biological Report 88(14) May 1988 Synopsis of the Biological Data on the Loggerhead Sea Turtle Caretta caretta (Linnaeus 1758) C. Kenneth Dodd, Jr. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service National Ecology Research Center 412 N.E. -

Mediterranean Triton Charonia Lampas Lampas (Gastropoda: Caenogastropoda): Report on Captive Breeding

ISSN: 0001-5113 ACTA ADRIAT., ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC PAPER AADRAY 57(2): 263 - 272, 2016 Mediterranean triton Charonia lampas lampas (Gastropoda: Caenogastropoda): report on captive breeding Mauro CAVALLARO*1, Enrico NAVARRA2, Annalisa DANZÉ2, Giuseppa DANZÈ2, Daniele MUSCOLINO1 and Filippo GIARRATANA1 1Department of Veterinary Sciences, University of Messina, Polo Universitario dell’Annunziata, 98168 Messina, Italy 2Associazione KURMA, via Andria 8, c/o Acquario Comunale di Messina-CESPOM, 98123 Messina, Italy *Corresponding author: [email protected] Two females and a male triton of Charonia lampas lampas (Linnaeus, 1758) were collected from March 2010 to September 2012 in S. Raineri peninsula in Messina, (Sicily, Italy). They were reared in a tank at the Aquarium of Messina. Mussels, starfish, and holothurians were provided as feed for the tritons. Spawning occurred in November 2012, lasted for 15 days, yielding a total number of 500 egg capsules, with approximately 2.0-3.0 x 103 eggs/capsule. The snail did not eat during the month, in which spawned. Spawning behaviour and larval development of the triton was described. Key words: Charonia lampas lampas, Gastropod, triton, veliger, reproduction INTRODUCTION in the Western in the Eastern Mediterranean with probable co-occurrence in Malta (BEU, 1985, The triton Charonia seguenzae (ARADAS & 1987, 2010). BENOIT, 1870), in the past reported as Charonia The Gastropod Charonia lampas lampas variegata (CLENCH AND TURNER, 1957) or Cha- (Linnaeus, 1758) is a large Mediterranean Sea ronia tritonis variegata (BEU, 1970), was recently and Eastern Atlantic carnivorous mollusk from classified as a separate species present only in the Ranellidae family, Tonnoidea superfamily, the Eastern Mediterranean Sea (BEU, 2010). -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: PATTERNS IN

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: PATTERNS IN DIVERSITY AND DISTRIBUTION OF BENTHIC MOLLUSCS ALONG A DEPTH GRADIENT IN THE BAHAMAS Michael Joseph Dowgiallo, Doctor of Philosophy, 2004 Dissertation directed by: Professor Marjorie L. Reaka-Kudla Department of Biology, UMCP Species richness and abundance of benthic bivalve and gastropod molluscs was determined over a depth gradient of 5 - 244 m at Lee Stocking Island, Bahamas by deploying replicate benthic collectors at five sites at 5 m, 14 m, 46 m, 153 m, and 244 m for six months beginning in December 1993. A total of 773 individual molluscs comprising at least 72 taxa were retrieved from the collectors. Analysis of the molluscan fauna that colonized the collectors showed overwhelmingly higher abundance and diversity at the 5 m, 14 m, and 46 m sites as compared to the deeper sites at 153 m and 244 m. Irradiance, temperature, and habitat heterogeneity all declined with depth, coincident with declines in the abundance and diversity of the molluscs. Herbivorous modes of feeding predominated (52%) and carnivorous modes of feeding were common (44%) over the range of depths studied at Lee Stocking Island, but mode of feeding did not change significantly over depth. One bivalve and one gastropod species showed a significant decline in body size with increasing depth. Analysis of data for 960 species of gastropod molluscs from the Western Atlantic Gastropod Database of the Academy of Natural Sciences (ANS) that have ranges including the Bahamas showed a positive correlation between body size of species of gastropods and their geographic ranges. There was also a positive correlation between depth range and the size of the geographic range. -

THE LISTING of PHILIPPINE MARINE MOLLUSKS Guido T

August 2017 Guido T. Poppe A LISTING OF PHILIPPINE MARINE MOLLUSKS - V1.00 THE LISTING OF PHILIPPINE MARINE MOLLUSKS Guido T. Poppe INTRODUCTION The publication of Philippine Marine Mollusks, Volumes 1 to 4 has been a revelation to the conchological community. Apart from being the delight of collectors, the PMM started a new way of layout and publishing - followed today by many authors. Internet technology has allowed more than 50 experts worldwide to work on the collection that forms the base of the 4 PMM books. This expertise, together with modern means of identification has allowed a quality in determinations which is unique in books covering a geographical area. Our Volume 1 was published only 9 years ago: in 2008. Since that time “a lot” has changed. Finally, after almost two decades, the digital world has been embraced by the scientific community, and a new generation of young scientists appeared, well acquainted with text processors, internet communication and digital photographic skills. Museums all over the planet start putting the holotypes online – a still ongoing process – which saves taxonomists from huge confusion and “guessing” about how animals look like. Initiatives as Biodiversity Heritage Library made accessible huge libraries to many thousands of biologists who, without that, were not able to publish properly. The process of all these technological revolutions is ongoing and improves taxonomy and nomenclature in a way which is unprecedented. All this caused an acceleration in the nomenclatural field: both in quantity and in quality of expertise and fieldwork. The above changes are not without huge problematics. Many studies are carried out on the wide diversity of these problems and even books are written on the subject. -

Download Full Article 1.6MB .Pdf File

Memoirs of the National Museum of Victoria https://doi.org/10.24199/j.mmv.1962.25.10 ADDITIONS TO MARINE MOLLUSCA 177 1 May 1962 ADDITIONS TO THE MARINE MOLLUSCAN FAUNA OF SOUTH EASTERN AUSTRALIA INCLUDING DESCRIPTIONS OF NEW GENUS PILLARGINELLA, SIX NEW SPECIES AND TWO SUBSPECIES. Charles J. Gabriel, Honorary Associate in Gonchology, National Museum of Victoria. Introduction. It has always been my conviction that the spasmodic and haphazard collecting so far undertaken has not exhausted the molluscan species to be found in the deeper waters of South- eastern Australia. Only two large single collections have been made; first by the vessel " Challenger " in 1874 at Station 162 off East Moncoeur Island in 38 fathoms. These collections were described in the " Challenger " reports by Rev. Boog. Watson (Gastropoda) and E. A. Smith (Pelecypoda). In the latter was included a description of a shell Thracia watsoni not since taken in Victoria though dredged by Mr. David Howlett off St. Francis Island, South Australia. In 1910 the F. I. S. " Endeavour " made a number of hauls both north and south of Gabo Island and off Cape Everard. The u results of this collecting can be found in the Endeavour " reports. T. Iredale, 1924, published the results of shore and dredging collections made by Roy Bell. Since this time continued haphazard collecting has been carried out mostly as a hobby by trawler fishermen either for their own interest or on behalf of interested friends. Although some of this material has reached the hands of competent workers, over the years the recording of new species has probably been delayed. -

Structure of Molluscan Communities in Shallow Subtidal Rocky Bottoms of Acapulco, Mexico

Turkish Journal of Zoology Turk J Zool (2019) 43: 465-479 http://journals.tubitak.gov.tr/zoology/ © TÜBİTAK Research Article doi:10.3906/zoo-1810-2 Structure of molluscan communities in shallow subtidal rocky bottoms of Acapulco, Mexico 1 1 2, José Gabriel KUK DZUL , Jesús Guadalupe PADILLA SERRATO , Carmina TORREBLANCA RAMÍREZ *, 2 2 2 Rafael FLORES GARZA , Pedro FLORES RODRÍGUEZ , Ximena Itzamara MUÑIZ SÁNCHEZ 1 Cátedras CONACYT-Marine Ecology Faculty, Autonomous University of Guerrero, Fraccionamiento Las Playas, Acapulco, Guerrero, Mexico 2 Marine Ecology Faculty, Autonomous University of Guerrero, Fraccionamiento Las Playas, Acapulco, Guerrero, Mexico Received: 02.10.2018 Accepted/Published Online: 10.07.2019 Final Version: 02.09.2019 Abstract: The objective of this study was to determine the structure of molluscan communities in shallow subtidal rocky bottoms of Acapulco, Mexico. Thirteen samplings were performed at 8 stations in 2012 (seven samplings), 2014 (four), and 2015 (two). The collection of the mollusks in each station was done at a maximum depth of 5 m for 1 h by 3 divers. A total of 2086 specimens belonging to 89 species, 36 families, and 3 classes of mollusks were identified. Gastropoda was the most diverse and abundant group. Calyptreaidae, Columbellidae, and Muricidae had >5 species, but Pisaniidae, Conidae, Fasciolariidae, and Muricidae had ≥15% of relative abundance. Most species found in this study were recorded in the rocky intertidal zone, and 10 species were restricted to the rocky subtidal zone. The affinity in the composition of the species during 2012–2015 had a low similarity (25%), but we could differentiate natural and anthropogenic effects according to malacological composition. -

Fossil Flora and Fauna of Bosnia and Herzegovina D Ela

FOSSIL FLORA AND FAUNA OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA D ELA Odjeljenje tehničkih nauka Knjiga 10/1 FOSILNA FLORA I FAUNA BOSNE I HERCEGOVINE Ivan Soklić DOI: 10.5644/D2019.89 MONOGRAPHS VOLUME LXXXIX Department of Technical Sciences Volume 10/1 FOSSIL FLORA AND FAUNA OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA Ivan Soklić Ivan Soklić – Fossil Flora and Fauna of Bosnia and Herzegovina Original title: Fosilna flora i fauna Bosne i Hercegovine, Sarajevo, Akademija nauka i umjetnosti Bosne i Hercegovine, 2001. Publisher Academy of Sciences and Arts of Bosnia and Herzegovina For the Publisher Academician Miloš Trifković Reviewers Dragoljub B. Đorđević Ivan Markešić Editor Enver Mandžić Translation Amra Gadžo Proofreading Amra Gadžo Correction Sabina Vejzagić DTP Zoran Buletić Print Dobra knjiga Sarajevo Circulation 200 Sarajevo 2019 CIP - Katalogizacija u publikaciji Nacionalna i univerzitetska biblioteka Bosne i Hercegovine, Sarajevo 57.07(497.6) SOKLIĆ, Ivan Fossil flora and fauna of Bosnia and Herzegovina / Ivan Soklić ; [translation Amra Gadžo]. - Sarajevo : Academy of Sciences and Arts of Bosnia and Herzegovina = Akademija nauka i umjetnosti Bosne i Hercegovine, 2019. - 861 str. : ilustr. ; 25 cm. - (Monographs / Academy of Sciences and Arts of Bosnia and Herzegovina ; vol. 89. Department of Technical Sciences ; vol. 10/1) Prijevod djela: Fosilna flora i fauna Bosne i Hercegovine. - Na spor. nasl. str.: Fosilna flora i fauna Bosne i Hercegovine. - Bibliografija: str. 711-740. - Registri. ISBN 9958-501-11-2 COBISS/BIH-ID 8839174 CONTENTS FOREWORD ........................................................................................................... -

CONE SHELLS - CONIDAE MNHN Koumac 2018

Living Seashells of the Tropical Indo-Pacific Photographic guide with 1500+ species covered Andrey Ryanskiy INTRODUCTION, COPYRIGHT, ACKNOWLEDGMENTS INTRODUCTION Seashell or sea shells are the hard exoskeleton of mollusks such as snails, clams, chitons. For most people, acquaintance with mollusks began with empty shells. These shells often delight the eye with a variety of shapes and colors. Conchology studies the mollusk shells and this science dates back to the 17th century. However, modern science - malacology is the study of mollusks as whole organisms. Today more and more people are interacting with ocean - divers, snorkelers, beach goers - all of them often find in the seas not empty shells, but live mollusks - living shells, whose appearance is significantly different from museum specimens. This book serves as a tool for identifying such animals. The book covers the region from the Red Sea to Hawaii, Marshall Islands and Guam. Inside the book: • Photographs of 1500+ species, including one hundred cowries (Cypraeidae) and more than one hundred twenty allied cowries (Ovulidae) of the region; • Live photo of hundreds of species have never before appeared in field guides or popular books; • Convenient pictorial guide at the beginning and index at the end of the book ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The significant part of photographs in this book were made by Jeanette Johnson and Scott Johnson during the decades of diving and exploring the beautiful reefs of Indo-Pacific from Indonesia and Philippines to Hawaii and Solomons. They provided to readers not only the great photos but also in-depth knowledge of the fascinating world of living seashells. Sincere thanks to Philippe Bouchet, National Museum of Natural History (Paris), for inviting the author to participate in the La Planete Revisitee expedition program and permission to use some of the NMNH photos.