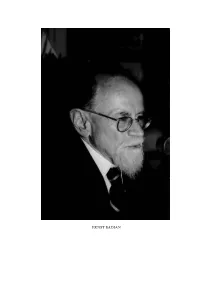

PETER MARSHALL FRASER 135 PETER FRASER Photograph: B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hill View Rare Plants, Summer Catalogue 2011, Australia

Summer 2011/12 Hill View Rare Plants Calochortus luteus Calochortus superbus Susan Jarick Calochortus albidus var. rubellus 400 Huon Road South Hobart Tas 7004 Ph 03 6224 0770 Summer 2011/12 400 Huon Road South Hobart Tasmania, 7004 400 Huon Road South Hobart Tasmania, 7004 Summer 2011/12 Hill View Rare Plants Ph 03 6224 0770 Ph 03 6224 0770 Hill View Rare Plants Marcus Harvey’s Hill View Rare Plants 400 Huon Road South Hobart Tasmania, 7004 Welcome to our 2011/2012 summer catalogue. We have never had so many problems in fitting the range of plants we have “on our books” into the available space! We always try and keep our lists “democratic” and balanced although at times our prejudices show and one or two groups rise to the top. This year we are offering an unprecedented range of calochortus in a multiplicity of sizes, colours and flower shapes from the charming fairy lanterns of C. albidus through to the spectacular, later-flowering mariposas with upward-facing bowl-shaped flowers in a rich tapestry of shades from canary-yellow through to lilac, lavender and purple. Counterpoised to these flashy dandies we are offering an assortment of choice muscari whose quiet charm, softer colours and Tulipa vvedenskyi Tecophilaea cyanocrocus Violacea persistent flowering make them no less effective in the winter and spring garden. Standouts among this group are the deliciously scented duo, M. muscarimi and M. macrocarpum and the striking and little known tassel-hyacith, M. weissii. While it has its devotees, many gardeners are unaware of the qualities of the large and diverse tribe of “onions”, known as alliums. -

Monuments, Materiality, and Meaning in the Classical Archaeology of Anatolia

MONUMENTS, MATERIALITY, AND MEANING IN THE CLASSICAL ARCHAEOLOGY OF ANATOLIA by Daniel David Shoup A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Art and Archaeology) in The University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Professor Elaine K. Gazda, Co-Chair Professor John F. Cherry, Co-Chair, Brown University Professor Fatma Müge Göçek Professor Christopher John Ratté Professor Norman Yoffee Acknowledgments Athena may have sprung from Zeus’ brow alone, but dissertations never have a solitary birth: especially this one, which is largely made up of the voices of others. I have been fortunate to have the support of many friends, colleagues, and mentors, whose ideas and suggestions have fundamentally shaped this work. I would also like to thank the dozens of people who agreed to be interviewed, whose ideas and voices animate this text and the sites where they work. I offer this dissertation in hope that it contributes, in some small way, to a bright future for archaeology in Turkey. My committee members have been unstinting in their support of what has proved to be an unconventional project. John Cherry’s able teaching and broad perspective on archaeology formed the matrix in which the ideas for this dissertation grew; Elaine Gazda’s support, guidance, and advocacy of the project was indispensible to its completion. Norman Yoffee provided ideas and support from the first draft of a very different prospectus – including very necessary encouragement to go out on a limb. Chris Ratté has been a generous host at the site of Aphrodisias and helpful commentator during the writing process. -

The Tomb Architecture of Pisye–Pladasa Koinon

cedrus.akdeniz.edu.tr CEDRUS Cedrus VIII (2020) 351-381 The Journal of MCRI DOI: 10.13113/CEDRUS.202016 THE TOMB ARCHITECTURE OF PISYE – PLADASA KOINON PISYE – PLADASA KOINON’U MEZAR MİMARİSİ UFUK ÇÖRTÜK∗ Abstract: The survey area covers the Yeşilyurt (Pisye) plain Öz: Araştırma alanı, Muğla ili sınırları içinde, kuzeyde Ye- in the north, Sarnıçköy (Pladasa) and Akbük Bay in the şilyurt (Pisye) ovasından, güneyde Sarnıçköy (Pladasa) ve south, within the borders of Muğla. The epigraphic studies Akbük Koyu’nu da içine alan bölgeyi kapsamaktadır. Bu carried out in this area indicate the presence of a koinon alanda yapılan epigrafik araştırmalar bölgenin önemli iki between Pisye and Pladasa, the two significant cities in the kenti olan Pisye ve Pladasa arasında bir koinonun varlığını region. There are also settlements of Londeis (Çiftlikköy), işaret etmektedir. Koinonun territoriumu içinde Londeis Leukoideis (Çıpı), Koloneis (Yeniköy) in the territory of the (Çiftlikköy), Leukoideis (Çırpı), Koloneis (Yeniköy) yerle- koinon. During the surveys, many different types of burial şimleri de bulunmaktadır. Dağınık bir yerleşim modeli structures were encountered within the territory of the koi- sergileyen koinon territoriumunda gerçekleştirilen yüzey non, where a scattered settlement model is visible. This araştırmalarında farklı tiplerde birçok mezar yapıları ile de study particularly focuses on vaulted chamber tombs, karşılaşılmıştır. Bu çalışma ile özellikle territoriumdaki chamber tombs and rock-cut tombs in the territory. As a tonozlu oda mezarlar, oda mezarlar ve kaya oygu mezarlar result of the survey, 6 vaulted chamber tombs, 6 chamber üzerinde durulmuştur. Yapılan araştırmalar sonucunda 6 tombs and 16 rock-cut tombs were evaluated in this study. -

Dissertation Master

APOSTROPHE TO THE GODS IN OVID’S METAMORPHOSES, LUCAN’S PHARSALIA, AND STATIUS’ THEBAID By BRIAN SEBASTIAN A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2013 1 © 2013 Brian Sebastian 2 To my students, for believing in me 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A great many people over a great many years made this possible, more than I could possibly list here. I must first thank my wonderful, ideal dissertation committee chair, Dr. Victoria Pagán, for her sage advice, careful reading, and steadfast encouragement throughout this project. When I grow up, I hope I can become half the scholar she is. For their guidance and input, I also thank the members of my dissertation committee, Drs. Jennifer Rea, Robert Wagman, and Mary Watt. I am very lucky indeed to teach at the Seven Hills School, where the administration has given me generous financial support and where my colleagues and students have cheered me on at every point in this degree program. For putting up with all the hours, days, and weeks that I needed to be away from home in order to indulge this folly, I am endebted to my wife, Kari Olson. I am grateful for the best new friend that I made on this journey, Generosa Sangco-Jackson, who encouraged my enthusiasm for being a Gator and made feel like I was one of the cool kids whenever I was in Gainesville. I thank my parents, Ray and Cindy Sebastian, for without the work ethic they modeled for me, none of the success I have had in my academic life would have been possible. -

La Mythologie De Glaucus Dans L'ode I, 7 D 'Horace

COLLECTION LATOMUS VOL. II HomIDages a""' Joseph Bidez et a""' Franz Culllont LATOMUS REVUE D'ÉTUDES LATINES 214, Avenue Brugmann, BRUXELLES La Mythologie de Glaucus dans l'ode I, 7 d 'Horace On est généralement d'accord pour admettre la vieille scolie de Porphyrion selon laquelle le destinataire de la belle ode 7 du li vre I des Odes d'Horace n'est autre que le célèbre Plancus, géné ral de César, ami de Cicéron, épistolier remarquable (1), pàrtisan d'Antoine et transfuge passé à Octave in extremis non sans avoir été courtisan fort servile de Cléopâtre. Mais, à propos de la même ode, la critique éprouve un certain mal à justifier les allusions my- · thiques qui s'y trouvent et particulièrement l'association d'idées par laquelle Teucer de Salamine est annexé à la conclusion de l'ode. Kiessling-Heinze dans l'édition Weidmann de 1930, estime qu'il ne faut pas chercher d'explication (li). Nous avons, quant à nous, vé rifié maintes fois l'étonnante subtilité du poète lorsqu'il s'agit de sertir son développement de savoureuses allusions - toujours quel- . que peu satiriques au fait qui le préoccupe principalement. Ici nous avons sans trop de pèin'ê été mis sur la voie de l'énigme par une note de Velleius Paterculus (8). Il conviertt d'en donner la tra duction: « Comme ensuite grandissaient en lui (Antoine) la flamme de son amour pour Cléopâtre et l'intensité de ses vices - lesquels sont toujours alimentés par le pouvoir, la licence et les flatteries - il décida de porter la guerre contre sa patrie. -

Lindos, Rhodos Λίνδος, Ρόδος

Lindos, Rhodos Λίνδος, Ρόδος Bouldering around Lindos Λίνδος, Ρόδος Several new bouldering sites near the famous town of Lindos on the beautiful island of Rhodes. The rock can be sharp in places but there is acres of potential. ACROPOLIS VIEW, LINDOS The view from the boulders. Park in the popular photo spot beside the Amphitheatre Club – just north of Lindos. The boulders are below some amazing looking cliffs facing the acropolis of ancient Lindos. The mighty pinnacle. The first climbs are on the tufa-ridden seaward face: 1/ Undercutter 5+ Sit start and undercut past the sharpest holds. 2/ Tufa Tussle 5+ Sit start and wrestle up the tufa. 1 2 Unknown Stones Page 1 Lindos, Rhodos Λίνδος, Ρόδος The next problems all start sat in the cave below the pinnacle: 3/ Apollo’s Bow 6b Sit start. Fight out of the cave and make an exacting leftwards traverse of the break. 4/ Needle of Helios 6a Sit start. The fine face fairly direct. 5/ The Sun’s Tower 6a Sit Start. The right arête. Avoid the adjoining rock. There are tons of other boulders here but the next prizes are on the big cyclopean rock. It all gets a bit highball: 3,4,5 8 9 10 6 7 9/ Cyclopean 3+ (English Hard Severe) The left edge of the cave. 6/ Skull Hole 3+ (English Severe) The right edge of the hole and the capping 10/ Before Tartarus 5 roof. Also serves as a descent. Sit start. Take the wall right of the cave. 7/ Crimps 4+Sit start. -

ERNST BADIAN Ernst Badian 1925–2011

ERNST BADIAN Ernst Badian 1925–2011 THE ANCIENT HISTORIAN ERNST BADIAN was born in Vienna on 8 August 1925 to Josef Badian, a bank employee, and Salka née Horinger, and he died after a fall at his home in Quincy, Massachusetts, on 1 February 2011. He was an only child. The family was Jewish but not Zionist, and not strongly religious. Ernst became more observant in his later years, and received a Jewish funeral. He witnessed his father being maltreated by Nazis on the occasion of the Reichskristallnacht in November 1938; Josef was imprisoned for a time at Dachau. Later, so it appears, two of Ernst’s grandparents perished in the Holocaust, a fact that almost no professional colleague, I believe, ever heard of from Badian himself. Thanks in part, however, to the help of the young Karl Popper, who had moved to New Zealand from Vienna in 1937, Josef Badian and his family had by then migrated to New Zealand too, leaving through Genoa in April 1939.1 This was the first of Ernst’s two great strokes of good fortune. His Viennese schooling evidently served Badian very well. In spite of knowing little English at first, he so much excelled at Christchurch Boys’ High School that he earned a scholarship to Canterbury University College at the age of fifteen. There he took a BA in Classics (1944) and MAs in French and Latin (1945, 1946). After a year’s teaching at Victoria University in Wellington he moved to Oxford (University College), where 1 K. R. Popper, Unended Quest: an Intellectual Autobiography (La Salle, IL, 1976), p. -

The Ancient Water System At

AGRICULTURAL TERRACES AND FARMSTEADS OF BOZBURUN PENINSULA IN ANTIQUITY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF THE MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY VOLKAN DEMİRCİLER IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN DEPARTMENT OF SETTLEMENT ARCHAEOLOGY FEBRUARY 2014 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Meliha ALTUNIŞIK Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dr. D. Burcu ERCİYAS Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dr. Numan TUNA Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Asuman G. TÜRKMENOĞLU (METU, GEOE) Prof. Dr. Numan TUNA (METU, SA) Prof. Dr. Sevgi AKTÜRE (METU, CRP) Prof. Dr. Yaşar E. ERSOY (HİTİT UNIV, ARCHAEO) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Lale ÖZGENEL (METU, ARCH) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last Name: Volkan DEMİRCİLER Signature: iii ABSTRACT AGRICULTURAL TERRACES AND FARMSTEADS OF BOZBURUN PENINSULA IN ANTIQUITY DEMİRCİLER, Volkan Ph.D., Department of Settlement Archaeology Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Numan TUNA February 2014, 158 pages In this thesis, the agricultural terraces and farmsteads lying in a region which encompasses the study area limited with the Turgut Village in the north and beginning of the Loryma territorium in the south, in the modern Bozburun Peninsula (also acknowledged as the Incorporated Peraea in the ancient period) are examined and questioned. -

The Greco-Roman East: Politics, Culture, Society, Volume XXXI - Edited by Stephen Colvin Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521828759 - The Greco-Roman East: Politics, Culture, Society, Volume XXXI - Edited by Stephen Colvin Index More information Index Abydenus 187 Aphrodisias (Caria) Achaean League 146, 148 sympoliteia with Plarasa 162–3, 172, 179 Achaeans Aphrodite in foundation of Soloi 184 Stratonikis 153 Achaios 149 Apollo 167, 173, 226 adlectio 111 Lairbenos 4, Lyrboton 36, Tarsios 5, Tiamos Aelius Ponticus 102, 103, 116 22 Aetolian League 146, 148 Lycian 58–9 Agatharchides (FGrHist 86 F16) Apollodoros Metrophanes (Miletos) 166 Aigai (Cilicia) 206 Apollonia (Crete) 148 Akalissos (Lycia) 171 Apollonis (Lydia) 149 akathartia see purity Apollonos Hieron (Lydia) 4 Akmonia 4 Arados (Phoenicia) 205 Al Mina 186 Aramaic Aleppo/Beroea 124 used (written) in Cilicia 190, 192, 195–6 Alexander the Great 156 Aratus 200, 206 southern Asia Minor, campaign 198 arbitration 32 Alexander Polyhistor 187 archiatros 100, 101, 103, 107 Alexandreia (Troas) 150 architecture alphabet Greek influence at Dura 121 Greek 45; place of adaptation 190–1 Parthian 132 Lycian 45 Argos Phrygian 191 mythological (kinship) ties with Amos (Rhodian Peraia) 177 Cilicia 198–9; Aigai 206; Soloi 195; Amphilochos 183–4, 195 Tarsos 184, 206 Anatolian languages Aristotle, on solecism 181 disappearance 203–4; see individual Arrian (Anab. 1.26–2.5) 197, 202 languages Arsinoe (Cilicia) 199 Anchialos (Cilicia) Artemis 21, 60–61 (?), 166, 226 foundation by ‘Sardanapalus’ 198 Pergaia 41 Antigonos Monophthalmos 150, 162, 171, Arykanda (Lycia) 178 sympoliteia with Tragalassa Antioch -

PETER FRASER Photograph: B

PETER FRASER Photograph: B. J. Harris, Oxford Peter Marshall Fraser 1918–2007 THE SUBJECT OF THIS MEMOIR was for many decades one of the two pre- eminent British historians of the Hellenistic age, which began with Alexander the Great. Whereas the other, F. W. Walbank (1909–2008),1 concentrated on the main literary source for the period, the Greek histor- ian Polybius, Fraser’s main expertise was epigraphic. They both lived to ripe and productive old ages, and both were Fellows of this Academy for an exceptionally long time, both having been elected aged 42 (Walbank was FBA from 1951 to 2008, Fraser from 1960 to 2007). Peter Fraser was a tough, remarkably good-looking man of middle height, with jet-black hair which turned a distinguished white in his 60s, but never disappeared altogether. When he was 77, a Times Higher Education Supplement profile of theLexicon of Greek Personal Names (for which see below, p. 179) described him as ‘a dashing silver-haired don’. He was attract ive to women even at a fairly advanced age and when slightly stout; in youth far more so. The attraction was not merely physical. He was exceptionally charming and amusing company when not in a foul mood, as he not infrequently was. He had led a far more varied and exciting life than most academics, and had a good range of anecdotes, which he told well. He could be kind and generous, but liked to disguise it with gruffness. He could also be cruel. He was, in fact, a bundle of contradictions, and we shall return to this at the end. -

Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 8 | 1995 Varia Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion Angelos Chaniotis and Eftychia Stavrianopoulou Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/605 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.605 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 1995 Number of pages: 205-266 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Angelos Chaniotis and Eftychia Stavrianopoulou, « Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion », Kernos [Online], 8 | 1995, Online since 11 April 2011, connection on 16 September 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/kernos/605 Kernos Kernos, 8 (1995), p, 205-266. EpigrapWc Bulletin for Greek Religion 1991 (EBGR) This fifth issue of BEGR presents the publications of 1991 along with several addenda to BEGR 1987-1990. The division of the work between New York and Heidelberg, for the first time this year, caused certain logistical prablems, which can be seen in several gaps; some publications of 1991 could not be considered for this issue and will be included in the next BEGR, together with the publications of 1992. We are optimistic that in the future we will be able to accelerate the presentation of epigraphic publications. The principles explained in Kernos, 4 (991), p. 287-288 and Kernos, 7 (994), p. 287 apply also to this issue, The abbreviations used are those of L'Année Philologique and the Supplementum Bpigraphicum Graecum. We remind our readers that the bulletin is not a general bibliography on Greek religion; works devoted exclusively to religious matters (marked here with an asterisk) are presented very briefly, even if they make extensive use of inscriptions, In exceptional cases (see n° 87) we include in our bulletin studies on the Linear B tablets. -

The Representation of Populares in the Late Roman Republic

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kent Academic Repository QUA RE QUI POSSUM NON ESSE POPULARIS: THE REPRESENTATION OF POPULARES IN THE LATE ROMAN REPUBLIC. by Michael A. Nash A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Research Department of Classical and Archaeological Studies School of European Culture and Languages University of Kent September 2015 (Thesis word count: 39,688) Abstract The terms popularis and optimate have been employed in both ancient and modern literature to interpret late Roman Republican politics. The purpose of this work is to express the diversity and change of the popularis label from 133 to 88 B.C. as a consequence of developing political practices. A chronological assessment of five key popularis tribunes in this period; Ti. Sempronius Gracchus, G. Sempronius Gracchus, L. Appuleius Saturninus, M. Livius Drusus and P. Sulpicius Rufus determines the variation in political methodologies exploited by these men in response to an optimate opposition. An assessment of Cicero’s works then considers how the discrepancies exhibited by these politicians could be manipulated for oratorical advantage. This subsequently reveals the perception of pre- Sullan populares in the time of Cicero, a generation later. This work ultimately aims to demonstrate the individualistic nature of late Republican politicians, the evolution of political practice in the period and the diverse employment of political labels in contemporary sources. 2 Acknowledgments This dissertation has come to fruition thanks to the assistance provided from numerous individuals. Primarily, I would like to express my gratitude to Professor Ray Laurence for his supervision throughout the year.