The Library of Hélion Jouffroy a Survey and Some Additional Identifications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Two Missals Printed for Wynkyn De Worde

TWO MISSALS PRINTED FOR WYNKYN DE WORDE GEORGE D. PAINTER, DENNIS E. RHODES, AND HOWARD M. NIXON The British Library has recently acquired two important and exceedingly rare editions of the Sarum Missal. These mere produced in Paris m I4gj and i^ii for Wynkyn de Worde and others., and are fully described in the second and third sections of this article. The first section gives a brief general account of the printing of the Sarum Missal for the English market during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. I THE English printers of the fifteenth century seemed curiously reluctant to print the major service-books of their own national liturgy, the rite of Sarum. This apparent disinclination cannot be explained by any lack of a market for such works. The Sarum Missal, above all, was certainly in greater demand than any other single book in pre- Reformation England, for every mass-saying priest and every church or chapel in the land was obliged to own or share a copy for daily use. Yet it is a striking fact that of the twelve known editions of the Sarum Missal during the incunable period all but two were printed abroad, in Paris, Basle, Venice, or Rouen, and imported to England. The cause of this paradoxical abstention was no doubt the inability of English printers to rise to the required magnificence of type-founts and woodcut decoration, and to meet the exceptional technical demands of high-quality red-printing, music printing, and beauty of setting, which were necessary for the chief service-book of the Roman Church in England. -

Latin Books Published in Paris, 1501-1540

Latin Books Published in Paris, 1501-1540 Sophie Mullins This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 6 September 2013 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, Sophie Anne Mullins hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 76,400 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2007 and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in September 2007; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between [2007] and 2013. (If you received assistance in writing from anyone other than your supervisor/s): I, …..., received assistance in the writing of this thesis in respect of [language, grammar, spelling or syntax], which was provided by …… Date 2/5/14 signature of candidate ……… 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. Date 2/5/14 signature of supervisor ……… 3. Permission for electronic publication: (to be signed by both candidate and supervisor) In submitting this thesis to the University of St Andrews I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations of the University Library for the time being in force, subject to any copyright vested in the work not being affected thereby. -

The Printing Revolution in Europe, 1455-1500 Author Index 1

Incunabula: The Printing Revolution in Europe, 1455-1500 Author Index Aaron Hakohen. Abraham ibn Ezra. Orhot Hayyim. Perush ha-Torah. [Spain or Portugal: Printer of Alfasi's Halakhot. [before Naples: Joseph ben Jacob Ashkenazi Gunzenhauser and his 1492?] son [Azriel]. 2 May 1488 ia00000500: GW 486; Offenberg 2; Thesaurus Tipog. ia00009300: H 23; Fava & Bresciano 262; Sander 4; IGI 6 = Hebraicae B37. VI E2; IDL 2448; Sajó-Soltész 1; Voulliéme, Berlin 3178; Fiche: IH 52 Ohly-Sack 4; Madsen 2; Proctor 6729; Cowley p.14; De Rossi (p.58) 21; Encyclopaedia Judaica 122; Freimann p.115; Abbey of the Holy Ghost. Freimann, Frankfurt 1; Goldstein 52; HSTC 73; Jacobs 53; Westminster: Wynkyn de Worde. [about 1497] Marx 1; Offenberg 56; Offenberg, Rosenthal 13; Schwab 46; ia00001500: Duff 1; H 19; STC 13609; Oates 4142; Proctor Steinschneider, Bodley 4221(1); Thesaurus Tipog. Hebraicae 9721; GW 1; Fac: ed. F. Jenkinson, Cambridge, 1907. A60; Wach II 158; Zedner p.22; GW 114. Fiche: EN 129 Fiche: IH 1 Abiosus, Johannes Baptista. Abrégé de la destruction de Troie. Dialogus in astrologiae defensionem cum vaticinio a Paris: Michel Le Noir. 1500 diluvio ad annos 1702. With additions by Domicus Palladius ia00009700: CIBN A-4, GW 119. Soranus. Fiche: RM 78 Venice: Franciscus Lapicida. 20 Oct. 1494 ia00008000: H 24*; GfT 2207; Klebs 1.1; Pellechet 17; CIBN Abstemius, Laurentius. A-2; IGI 2; IBP 1; IBE 2; Essling 756; Sander 1; Walsh Fabulae (Ed: Domicus Palladius Soranus). Aded: Aesopus: 2626A; Sheppard 4581; Proctor 5543; BSB-Ink A-2; GW 6. Fabulae (Tr: Laurentius Valla). -

Printing the Law in the 15Th Century with a Focus on Corpus Iuris Civilis

Printing R-Evolution and Society 1450-1500 Fifty Years that Changed Europe edited by Cristina Dondi chapter 4 Printing the Law in the 15th Century With a Focus on Corpus iuris civilis and the Works of Bartolus de Saxoferrato Maria Alessandra Panzanelli Fratoni 15cBOOKTRADE, University of Oxford, UK Abstract The editions of legal texts are a major and important part of 15th-century book output, amounting to about 15% of the surviving extant editions. The category comprehends two types of work: (a) the collections of Roman and Canon law, with their medieval supplements and commentaries; (b) acts and regulations produced by govern- ments and by local authorities as part of their day-to-day activity. After a general overview, this article focuses on the first group of texts, which offers an opportunity to address some key questions related to the impact of printing in a particular cultural context, that of the university. A study of legal texts printed in the 15th century aims to provide a relevant contribution to a better understanding of the impact of printing by comparing elements of continuity and discontinuity with the manuscript and later printed tradition. Keywords History of the book. Textual transmission. Incunabula. Scholarly book. Law books. Legal texts. Ius commune. Legal history. Corpus iuris civilis. Bartolus de Saxofer- rato. History of Universities. Summary 1 Introduction. – 2 Legal Texts in the Age of Print: An Overview. – 2.1 The Cat- egories of Law; Ius Commune and Iura Propria; Scholarly Production and Current Affairs – 2.2 Civil and Canon law: Scholarly Production. – 2.3 Periodisation of the Texts of Civil and Canon law. -

Antiquarian Books

JUSTIN CROFT Antiquarian Books exhibiting at the New York Antiquarian Book Fair 2016 booth A33 Justin Croft Antiquarian Books Ltd, ABA, ILAB, 7 West Street, Faversham, Kent, ME137JE, UK, [email protected] +44 1795 591111 mobile: +44 7725 845275 ECLIPSE OF THE SUN KING 1. [ALLARD, Carel]. Koninglyke Almanach: beginnende, met den aanvang der oorlogh, van anno 1701... waer in... de loop der zon der ongeregtigheid... door XVIII zinnebeelden in koopere plaaten vertoond word...; Almanach Royal. Commencement avec la guerre de l’an 1701. ‘Paris: Imprimerie Royale’, [but Amsterdam, c. 1706]. $4500 Small folio (319 × 200 mm), engraved title (in Dutch and French) and 18 plates (of which 12 are double page) with engraved or letterpress text, plus 6 additional plates loosely inserted, the called-for plates neatly mounted on guards in early (probably eighteenth-century) marbled wrappers. Former collector’s neat numbering to lower forecorners. Spine defective, a few plates slightly creased or dusty at margins. But overall very crisp and clean. FIRST EDITION of this collection of violently satirical plates directed against Louis XIV, Madame de Maintenon and Philip V of Spain during the War of the Spanish Succession, several linking their fortunes to solar eclipse of 1706. The plates are mostly by Carel Allard (1648-1709) and were etched and published separately as broadsides more or less simultaneously with the depicted contemporary events; and published as a collection c. 1706. Several of the plates have been attributed to Romeyn de Hooghe, though not securely. Both the broadsides and the collection are rare, held by only a few institutions. -

Festschrift HDL.Indd

Downloaded from SAS Space http://www.sas-space.sas.ac.uk Open Access books made available by the School of Advanced Study, University of London Press ***** Publication details: Medieval Londoners: essays to mark the eightieth birthday of Caroline M. Barron Edited by Elizabeth A. New and Christian Steer DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781912702152 ***** This edition published 2019 by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON PRESS SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU, United Kingdom ISBN 978-1-912702-15-2 (PDF edition) This work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses IHR Conference Series Medieval Londoners Essays to mark the eightieth birthday of Caroline Barron Edited by Elizabeth A. New and Christian Steer Medieval Londoners Essays to mark the eightieth birthday of Caroline M. Barron Medieval Londoners Essays to mark the eightieth birthday of Caroline M. Barron Edited by Elizabeth A. New and Christian Steer UNIVERSITY OF LONDON PRESS INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Published by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON PRESS SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU Text © contributors, 2019 Images © contributors and copyright holders named in captions, 2019 The authors have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as authors of this work. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Any third-party material in this book is published under the book’s Creative Commons license unless indicated otherwise in the credit line to the material. -

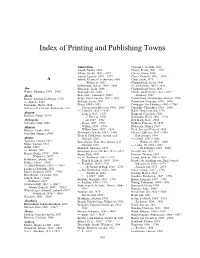

Index of Printing and Publishing Towns

Index of Printing and Publishing Towns Amsterdam Carpentier, Jacobus, 1633 Aboab, Eliahu, 1644 Chayer, Pierre, 1691 ± 1700 Athias, Joseph, 1661 ± 1667 Claesse, Frans, 1654 Autein, Laurens, 1670 ± 1671 Claesz, Cornelis, 1602 ± 1610 A Baardt, Rieuwert Dircksz van, 1644 Claus, Jacob, 1676 —, —, Widow of, 1652 Cloppenburgh, Evert, 1640 Bakkamude, Daniel, 1666 ± 1668 —, Jan Evertsz, 1603 ± 1630 A˚ bo Benjamin, Jacob, 1668 Cloppenburgh Press, 1640 Winter, Johannes, 1689 ± 1692 Benningh, Jan, 1655 Colom, Jacob Aertsz, 1633 ± 1671 Alcalá Benveniste, Immanuel, 1658? —, Johannes, 1648 Brocar, Arnaldo Guillén de, 1516 Berge, Pieter van den, 1661 ± 1665 Commelinus, Hieronymus, Heirs of, 1626 —, Juan de, 1541 Bisterus, Lucas, 1680 Commelyn, Casparus, 1660 ± 1669 Fernández, María, 1646 Blaeu, 1684 ± 1685 Compagnie des Libraires, 1685 ± 1700? Ximenez de Cisneros, Franciscus, 1517 —, Typographia Blaviana, 1663 ± 1693 Cunradus, Christoffel, 1651 ± 1660 —, Cornelis, 1635 ± 1648? Dalen, Daniel van den, 1700 Alençon —, Joan, I, 1635 ± 1675 Dankertz, Cornelius, 1659 Du Bois, Simon, 1530? —, —, I, Heirs of, 1679 Desbordes, Henri, 1683 ± 1700 Alethopolis —, —, II, 1687 ± 1701 Dittelbach, Pierre, 1689 Valerius, Cajus, 1665 —, Pieter, 1687 ± 1701 Du Bois, François, II, 1676 Alkmaar —, Willem, 1633 ± 1688 Du Fresne, Daniel, 1687 Meester, Jacob, 1605 —, Willem Jansz, 1617 ± 1639 Dyck, Jan van, Heirs of, 1685 Oorschot, Joannes, 1605 Blankaart, Cornelis, 1687 ± 1688 Elsevier, Officina, 1637 ± 1680 Blum & Conbalense, (pseud. of S. —, Bonaventure, 1608 Altdorf Mathijs), -

A Census of Print Runs for Fifteenth-Century Books

A Census of Print Runs for Fifteenth-Century Books Many historians seeking to measure the impact of the ‘printing revolution’ in fifteenth- century Europe have taken a quantitiative approach, multiplying the total of all editions by the number of copies in a typical edition. However, whereas the Incunable Short Title Catalog (ISTC) lists more than 28,000 fifteenth-century editions that are represented by surviving specimens, the number of lost editions will always remain indeterminate.1 The second factor in the equation – the typical or ‘average’ fifteenth-century print run – is just as indeterminate as the first, if not more so. Inevitably, the ‘editions × copies’ formula has produced estimates of fifteenth-century press production that range anywhere from eight million to more than twenty million pieces of reading material.2 Such irreconcilable results (in which the margin for error may be larger than the answer itself) only serve to demonstrate that any effort to arrive at a meaningful quantification of fifteenth-century press production will require a much more systematic analysis of the available data on print runs. The present study, a census of print runs for fifteenth-century books, takes a step in that direction by asking a much more basic question: what is the available data? The Problem In a typical example of the quantitative approach to the readership of one fifteenth- century text, Frederick R. Goff once demonstrated the popularity of the Postilla super epistolas et evangelia by Guillermus Parisiensis by noting that more -

Hier Finden Sie Bücherzeichen, Die Auf Die Ewigkeit (Aeternitas) Verweisen: Uroboros, Phönix Und Tempus

Hier finden Sie Bücherzeichen, die auf die Ewigkeit (Aeternitas) verweisen: Uroboros, Phönix und Tempus B41b, 1.2016 Auf die Ewigkeit verweisen die Bücherzeichen der nachstehend aufgeführten Drucker Daniel Bakkamunde Jean Gaudin Graziose Percacino Gimel Bergen (I.), und Blaise Petrail Gimel Bergen (II.) Jacques Gazeau Johannes Rastell und Gimel Bergen (III.) Jan van Ghelen und William Rastell Francesco Bindoni Giulio Guidobono Nicolaus Roth und Gaspare Bindoni und Ottaviano Guidobono Arnold Bon Orazio Gobbi Felix van Sambix d.J. Jean Bonfons d.Ä. Nikolaus Schreiber Henry Bynneman Hendrick Lodewycxsz van Haestens Barentsz Otto Smient David Hauth d.Ä. Abraham Jansz Canin Michel Hillen Jean Temporal Girolamo Cartolari, Jean de Tournes d.Ä. Baldassare Cartolari William Jaggard, und Jean de Tournes d.J. und Francesco Cartolari John Jaggard Matern Cholin und Isaac Jaggard Antoine Vincent d.Ä., und Peter Cholin Peter Jordan Antoine Vincent d.J. Simon de Colines und Barthelemy Vincent Dirck van Kalis Giovanni Dossena und Jacob Braat Jan van Waesberghe d.J. Guillermo Drouy William Williamson Robert le Mangnier Wynkyn de Worde Heinrich Falkenberg Simon Millanges Filoterpsi Filoponi Die Symbole der Ewigkeit: Aeternitas (männlich Aeternus, griech. Aion) war die personifizierte Ewigkeit. Als »Aeternitas Augusti«, als kaiserliche Ewigkeit, erscheint sie seit den Zeiten Kaiser Augustus’ (63 v.Chr.–14 n.Chr.) wird sie auf Inschriften von Münzen abgebildet. Erst unter Kaiser Titus Flavius Vespasian (9–79) wird sie als Frau bildlich dargestellt; hier- bei saß sie auf einem von Löwen oder von Elefanten gezogenen Wagen. Der italienische Dichter Barberino dell’Este beschrieb sie 1324 als Frau, deren Beine als Schlangen ausgebildet sind. -

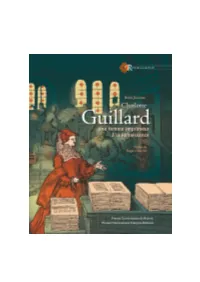

Charlotte Guillard Est Une Figure Exceptionnelle De La Renaissance Française

4 Financement de l’ouvrage Cet ouvrage est diffusé en accès ouvert dans le cadre du projet OpenEdition Books Select. Ce programme de financement participatif, coordonné par OpenEdition en partenariat avec Knowledge Unlatched et le consortium Couperin, permet aux bibliothèques de contribuer à la libération de contenus provenant d'éditeurs majeurs dans le domaine des sciences humaines et sociales. La liste des bibliothèques ayant contribué financièrement à la libération de cet ouvrage se trouve ici : https://www.openedition.org/22515. This book is published open access as part of the OpenEdition Books Select project. This crowdfunding program is coordinated by OpenEdition in partnership with Knowledge Unlatched and the French library consortium Couperin. Thanks to the initiative, libraries can contribute to unlatch content from key publishers in the Humanities and Social Sciences. Discover all the libraries that helped to make this book available open access: https:// www.openedition.org/22515?lang=en. 1 Charlotte Guillard est une figure exceptionnelle de la Renaissance française. Originaire du Maine, elle mène à Paris une carrière brillante dans la typographie. Veuve tour à tour des imprimeurs Berthold Rembolt et Claude Chevallon, elle administre en maîtresse femme l’atelier du Soleil d’Or pendant près de vingt ans, de 1537 à 1557. Sous sa direction, l’entreprise accapare le marché de l’édition juridique et des Pères de l’Église, publiant des éditions savantes préparées par quelques- uns des plus illustres humanistes parisiens (Antoine Macault, Jacques Toussain, Jean Du Tillet, Guillaume Postel…). Associant dans un même projet intellectuel les théologiens les plus conservateurs et les lettrés les plus épris de nouveauté, sa production témoigne de la vivacité des débats qui agitent les milieux intellectuels au siècle des Réformes. -

Wynkyn De Worde and Richard Pynson, and Include Biographical and Bibliographical Surveys, As Well As Case Studies of Each Printer‘S Liturgical Printing

Sarum Liturgical Printing in Tudor London Thesis submitted to Royal Holloway College, University of London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Jenifer Raub 2011 2 DECLARATION OF AUTHORSHIP I, Jenifer Raub, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: ................................................................................. Date: 9th September 2011 3 ABSTRACT This thesis consists of an archival study of early liturgical printing in Tudor London, focusing specifically on contextual and bibliographical examinations of the printed books of the Sarum rite (Use of Salisbury). Chapter 1 provides an introduction and background to Sarum liturgical books and the early book trade. Chapters 2 and 3 examine the work of two early London printers, Wynkyn de Worde and Richard Pynson, and include biographical and bibliographical surveys, as well as case studies of each printer‘s liturgical printing. Chapter 4 presents evidence of individual and institutional ownership of liturgical books and analyzes the market for liturgical books. Chapter 5 considers the last manifestations of Sarum liturgical printing, examining the impact of the liturgical reforms of the late Henrician and Edwardian churches, as well as the re-imposition of Catholicism under Mary I, on the production and provision of Sarum books. The three appendices present a database of printed copies of Sarum liturgical books and the total printed output of Wynkyn de Worde -

E-CATALOGUE 8 European Books, 1470-1817

♦ MUSINSKY RARE BOOKS ♦ 176 West 87th Street New York, New York 10024 E-CATALOGUE 8 No. 4 European books, 1470-1817 telephone: 212 579-2099 email: [email protected] ♦ MUSINSKY RARE BOOKS ♦ All the nutrients 1) MARCHESINUS, Johannes. Mammotrectus super Bibliam. Mainz: Peter Schoeffer, 10 November 1470. Folio (317 x 220 mm). Collation: [1-410 58; 6-710 88 (8-1); 96 10-1110 128 136 1410 154]. 129 leaves (of 130, without fol. 8/8 blank). For contents see Bod-inc M-080. 48 lines, double column. Type: 3:91G. Colophon on 15/3v and Fust- Schoeffer woodcut device printed in red. Six- to two-line initial spaces. Two large illuminated initials on first page, an I in gold with mauve pen- flourishing, and an F in blue with white foliate modelling, white and gold decorative infill, and leafy extenders in green, mauve and blue with four gold buds and one gold disk; rubricated in red: sporadic headlines, marginal chapter numbers in roman minuscules, Lombard initials, some with flourishes or marginal extenders, capital strokes and paragraph signs. Early notes in brown ink in a neat square hand are visible in the gutter between conjugate leaves 9/3 and 9/4. Tiny chip in opening gold initial, else in fine condition. Eighteenth-century German mottled calf, German printed floral-patterned endpapers, edges stained red (rebacked, preserving two 18th-century lettering pieces, corners restored). Provenance: Baron de Bethmann (sale Paris, Part 2, 30 May-2 June 1923, lot 151); extensive pencil notes on front flyleaf; Dr. Detlef Mauss, embossed stamp (with replica of the Fust & Schoeffer device), pencil acquisition date 17.3.1995, and an interlinear pencil note in the 1 ♦ MUSINSKY RARE BOOKS ♦ aforementioned page of notes (”Schrift von Baron Neufforge?! Nein!”); sold Christie’s New York, 24 May 2002, lot 128.