Note of Explanation Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INFORMAÇÃO TURÍSTICA E S R

R. Armando Martino R. Carlos B v . R. Lagoa Azul V . Corr o l R. Nelson u n t eia á A r i V o A . s R. Cel. Mar v R to A d . cílio F R. Dona a C R v ranc P P od. Bandeirantes r o . Gen. Edgard F u d de á z PARQUE SÃO e er t A r v. v. Casa V e M A i C edo Pujol a o R. Alfr i n DOMINGOS ag R. Our r c o de Paula o al ei h ç R. Dr César d ã ãe o R. Itapinima s R. Chic o Gr o m i S u osso R. L u q l to eão XIII SANTANA u Z R. M . Mora . Miguel Conejo r R . Z v A D acó R. Estela B . A élia SANTANA . J v R . C . PARQUE CIDADE Av. Ns. do Ó Z . Angelina Fr . Inajar de Souza a R. Chic v e c ire 1 DE TORONTO 2 3 v 4 5 de 6 7 8 h A i A PIQUERI r er i o o N i i Av. Ns. do Ó l Penitenciária do o P c a g i á R. Balsa r t Estado Carandiru ontes c s M . Casa V h a l v R. Maria Cândida n e i 48 98 i A r Jardim Botânico G7 A7 A 100 Serra da Cantareira 27 b o a Atrativos / Atractivos d t . G v n 49 99 A o Av. -

Sãopaulo Welcome to São Paulo São Paulo Em Números / São Paulo in Numbers

Índice Bem Vindo a São Paulo ................................................ 2 SãoPaulo Welcome to São Paulo São Paulo em números / São Paulo in numbers .................................................. 6 guia do profissional de turismo Acesso / Access .......................................................................................................... 10 Economias criativas / Creative economies ............................................................12 tourism professional guide Conheça São Paulo .................................................... 14 Get to know São Paulo Por que São Paulo é o melhor destino para seus negócios e eventos? .......... 16 Why is São Paulo the best destination for your business and events? A São Paulo Turismo apóia o seu evento .............................................................. 24 São Paulo Tourism supports your event O ponto alto do seu programa de incentivos ...................................................... 26 The highlight of your incentive program São Paulo Por Regiões ............................................... 36 São Paulo by Regions Berrini ........................................................................................................................... 38 Faria Lima & Itaim ......................................................................................................40 Paulista & Jardins ....................................................................................................... 42 Ibirapuera & Moema ..................................................................................................44 -

O Verde Na Metrópole: a Evolução Das Praças E Jardins Em Curitiba (1885-1916)

APARECIDA VAZ DA SILVA BAHLS O VERDE NA METRÓPOLE: A EVOLUÇÃO DAS PRAÇAS E JARDINS EM CURITIBA (1885-1916) Dissertação apresentada como requisito parcial à obtenção do grau de Mestre. Curso de Pós-Graduação em História, Setor de Ciências Humanas, Letras e Artes, Universidade Federal do Paraná. Orientadora: Prof.a Dr.a Maria Luiza Andreazza. Co-orientador: Prof. Dr. Magnus Roberto de Mello Pereira CURITIBA 1998 AGRADECIMENTOS À Fundação Cultural de Curitiba, sem a qual este trabalho não poderia ter se concretizado, em especial à Professora Oksana Boruszenko, Diretora do Patrimônio Histórico-Cultural. Aos professores Etelvina Maria de Castro Trindade, Magnus Roberto de Mello Pereira e Maria Luiza Andreazza, pela orientação e apoio. Aos funcionários dos arquivos pesquisados: Arquivo Público do Paraná, Biblioteca Pública do Paraná, Casa da Memória e, especialmente, a Helena Soares, do Museu Paranaense. A meus pais, pelo incentivo, e aos parentes e amigos: Aarão, Adão, Afonso, André, Antony, Edward, Fernanda, Gabriel, Gisele, Isabel, Marcelo e Solange. Com amor, ao meu marido Allan, pela compreensão, apoio e auxílio nos momentos difíceis. SUMÁRIO INTRODUÇÃO 01 PARTE I - A CIDADE E O VERDE 09 1 O VERDE NO SURGIMENTO DO URBANISMO MODERNO 10 1.1 A FÁBRICA EA CIDADE 11 1.2 A CIDADE E SUAS TRANSFORMAÇÕES NA ERA INDUSTRIAL 14 1.3 MORAR NA CIDADE INDUSTRIAL 17 1.4 0 PODER PÚBLICO E OS PROBLEMAS URBANOS 21 1.5 AS NOVAS CONCEPÇÕES URBANÍSTICAS 30 1.60 VERDE NA METRÓPOLE 37 2 O VERDE E O DESENVOLVIMENTO DO URBANISMO NO BRASIL 49 2.1 AS TRANSFORMAÇÕES URBANAS NO BRASIL OITOCENTISTA... -

CENTRO E BOM RETIRO IMPERDÍVEIS Banco Do Brasil Cultural Center Liberdade Square and Market Doze Edifícios E Espaços Históricos Compõem O Museu

R. Visc onde de T 1 2 3 4 5 6 aunay R. Gen. Flor . Tiradentes R. David Bigio v R. Paulino A 27 R. Barra do Tibaji Av C6 R. Rodolf Guimarães R. Par . Bom Jar Fashion Shopping Brás o Miranda Atrativos / Attractions Monumentos / Monuments es dal dim A 28 v B2 Fashion Center Luz . R. Mamor R. T C é r R. Borac é u R. Pedro Vicente 29 almud Thorá z Ferramentas, máquinas e artigos em borracha / eal e 1 1 i Academia Paulista de Letras C1 E3 “Apóstolo Paulo”, “Garatuja, “Marco Zero”, entre outros R. Mamor r e R. Sólon o R. R R. do Bosque d C3 Tools, machinery and rubber articles - Rua Florêncio de Abreu éia ARMÊNIA odovalho da Fonseca . Santos Dumont o 2 R. Gurantã R. do Ar D3 v Banco de São Paulo Vieira o S A R. Padr R. Luis Pachec u 30 l ecida 3 Fotografia / Photography - Rua Conselheiro Crispiniano D2 R. Con. Vic Batalhão Tobias de Aguiar B3 ente Miguel Marino R. Vitor R. Apar Comércio / Shopping 31 Grandes magazines de artigos para festas Air R. das Olarias R. Imbaúba 4 R. Salvador L osa Biblioteca Mário de Andrade D2 R. da Graça eme e brinquedos (atacado e varejo) / Large stores of party items and toys 5 BM&F Bovespa D3 A ena R. Araguaia en. P eição R. Cachoeira 1 R. Luigi Grego Murtinho (wholesale and retail) - Rua Barão de Duprat C4 R. T R. Joaquim 6 Acessórios automotivos / Automotive Accessories R. Anhaia R. Guarani R. Bandeirantes Caixa Cultural D3 apajós R. -

Revisão Do Plano Diretor

REVISÃO DO PLANO DIRETOR MINUTA DO ANTEPROJETO DE LEI COMPLEMENTAR Revisão 3 (07/12/2020) - conforme Memo GAB nº 4.413/2020. João Eduardo Dado Leite de Carvalho Prefeito Renato Gaspar Martins Vice-Prefeito Tássia Gélio Coleta Nossa Secretária Municipal de Planejamento André Luís Souza Figueiredo Secretário de Direitos Humanos Mônica Pesciotto de Carvalho Presidente do Fundo Social de José Ricardo Rodrigues da Cunha Solidariedade do Município Secretário Municipal de Esporte e Lazer Douglas Lisboa da Silva Mauro Del Álamo Procurador Geral do Município Secretário Municipal de Obras César Fernando Camargo Jair de Oliveira Secretário Municipal de Governo Secretário Municipal de Trânsito, Transporte e Segurança Miguel Maturana Filho Secretário Municipal da Administração Ronaldo Armando de Mattos Secretário Municipal de Transparência e Diogo Mendes Vicentini Controladoria Geral Secretário Municipal da Fazenda. Waldecy Antonio Bortoloti Márcia Cristina Fernandes Prado Reina Superintendente da SAEV Ambiental Secretária Municipal da Saúde Ederson Marcelo Batista Secretário Municipal da Educação Thiago Augusto Francisco Secretário Municipal da Assistência Social José Marcelino Poli Secretário Municipal da Cidade Silvia Brandão Cuenca Stipp Secretária Municipal da Cultura e Turismo. Flávio Augusto Piancenti Junior Secretário Municipal de Desenvolvimento Econômico Equipe de Coordenação da revisão do Plano Representante da Associação dos Engenheiros Diretor Participativo – Equipe PDP Arquitetos e Agrônomos da Região Votuporanga – SEARVO Tássia Gélio -

São Paulo January 4Th to 20Th, 2012

MENTORING AND LANGUAGE ACQUISITION IN BRAZIL (MLAB) São Paulo January 4th to 20th, 2012 Partner Institutions Harvard University David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies (DRCLAS) www.drclas.harvard.edu/brazil/student/mlab Caros participantes (Dear Participants), Sejam bem-vindos! It is a joy to have such a diverse, talented and dedicated group of students together from Harvard and throughout Brazil for the first edition of the Mentoring and Language Acquisition in Brazil (MLAB) program. Parabéns to all of you on your acceptances. The 15 Harvard College mentors in MLAB were selected from over 60 applicants. The 15 Brazilian mentees from Belo Horizonte, MG; Fortaleza, CE; Porto Alegre, RS; Rio de Janeiro, RJ; São José dos Campos, SP and São Paulo, SP join the program after successfully navigating extremely competitive scholarship selection processes in their sponsoring organizations and having interviews in English via Skype from afar. MLAB was inspired by our positive experiences running collaborative Harvard-Brazil programs over the past five years and by the exciting opportunity to help eliminate barriers to internationalization in Brazil and at Harvard. President Dilma Rousseff recently announced the goal of offering 100 thousand scholarships to Brazilians seeking to study in foreign universities. There is a talented pool of young students in Brazil with incredible life stories, overwhelming potential and an admirable eagerness to take advantage of the chance to study abroad. A large percentage of the most talented candidates, however, lack sufficient English-language abilities and direct contact with inspiring role models. Meanwhile, interest in Brazil at Harvard has skyrocketed in recent years. -

Exhibition Guide Silveira June 5, 2019

510 West 26 Street Alexander Gray Associates New York NY 10001 United States Tel: +1 212 399 2636 www.alexandergray.com Model for "Supersonic Goal" (Pacaembu Stadium, São Paulo, Brazil), 2004, enamel, adhesive vinyl, paper, and wood, 10.25h x 33.63w x 21d in (26.04h x 85.41w x 53.34d cm) Regina Silveira: Unrealized / Não feito June 5 – July 12, 2019 Alexander Gray Associates presents an exhibition of ten unrealized projects by multidisciplinary artist Regina Silveira. Emphasizing Silveira’s ongoing formal experimentation and conceptual interventions in architecture, the works on view provide an overview of site-specific installations and public art projects that were never realized in physical space. Regina Silveira: Unrealized / Não feito is the Gallery’s fifth solo presentation of Silveira’s work, and celebrates a decade since her first Gallery exhibition in 2009. A pioneering figure in Brazilian art, for over five decades Silveira has utilized surprise and illusion as methodologies for the destabilization of perspective and reality. Silveira began her career in the 1950s under the tutelage of expressionist Brazilian painter Iberê Camargo, studying lithography and woodcut, as well as painting. In the 1970s, Silveira experimented with printmaking and video, spearheading a movement of radical artistic production during a time of military repression in Brazil. Since the 1980s, Silveira has executed numerous large-scale installations in libraries, public plazas, roadways, parks, museum facades, public transit centers, and other institutional sites. The works on view in Unrealized / Não feito offer a unique glimpse into Silveira’s process and methodology and catalyze possibilities for future experimentation. -

Memoricidade.Pdf

memoricidadeV.1 - N.1 – Dezembro 2020 invisibilidades urbanas memoricidade sumário Revista do Museu da Cidade de São Paulo editorial Uma revista para o Museu da Cidade de São Paulo 6 Conselho editorial Editor Projeto gráfco e diagramação Beatriz Cavalcanti de Arruda Maurício Rafael Fajardo Ranzini Design João de Pontes Junior Arthur Fajardo e Claudia Ranzini ensaio A cidade, as memórias e as vozes rebeldes 8 José Henrique Siqueira Editores associados Alecsandra Matias de Oliveira Luiz Fernando Mizukami João de Pontes Junior Impressão Marcos Cartum Rafael Itsuo Takahashi Imprensa Ofcial do Estado - Imesp Preservação experimental para desinventar a tradição 14 Marília Bonas dossiê Marly Rodrigues Produção editorial Revisão Giselle Beiguelman Maurício Rafael Felipe Garofalo Cavalcanti Renata Lopes Del Nero Natália Godinho João de Pontes Junior O.CU.PAR: invisibilidades LGBTQIA+ na cidade de São Paulo 22 Maurício Rafael Foto de capa Bruno Puccinelli Coordenação Rafael Itsuo Takahashi Crianças em São Paulo, Praça da Sé, 1984 Marcos Cartum Silvia Shimada Borges Rosa Gauditano Museu dos invisíveis 28 Christian Ingo Lenz Dunker Visibilidades da cidade 36 Esta publicação é dedicada a Julio Abe Wakahara, falecido em novembro de 2020, cuja trajetória profssional, de mais de quatro décadas, trouxe notáveis contribuições para a museologia brasileira, tendo sido um dos primeiros a se dedicar ao patrimônio Abílio Ferreira imaterial. Julio Abe foi diretor, no fnal da década de 1970, da Seção Museu Histórico da Imagem Fotográfca da Cidade de São Paulo -

Destination Report

Miami , Flori daBuenos Aires, Argentina Overview Introduction Buenos Aires, Argentina, is a wonderful combination of sleek skyscrapers and past grandeur, a collision of the ultrachic and tumbledown. Still, there has always been an undercurrent of melancholy in B.A. (as it is affectionately known by expats who call Buenos Aires home), which may help explain residents' devotion to that bittersweet expression of popular culture in Argentina, the tango. Still performed—albeit much less frequently now—in the streets and cafes, the tango has a romantic and nostalgic nature that is emblematic of Buenos Aires itself. Travel to Buenos Aires is popular, especially with stops in the neighborhoods of San Telmo, Palermo— and each of its colorful smaller divisions—and the array of plazas that help make up Buenos Aires tours. Highlights Sights—Inspect the art-nouveau and art-deco architecture along Avenida de Mayo; see the "glorious dead" in the Cementerio de la Recoleta and the gorgeously chic at bars and cafes in the same neighborhood; shop for antiques and see the tango dancers at Plaza Dorrego and the San Telmo Street Fair on Sunday; tour the old port district of La Boca and the colorful houses along its Caminito street; cheer at a soccer match between hometown rivals Boca Juniors and River Plate (for the very adventurous only). Museums—Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires (MALBA: Coleccion Costantini); Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes; Museo Municipal de Arte Hispano-Americano Isaac Fernandez Blanco; Museo Historico Nacional; Museo de la Pasion Boquense (Boca football); one of two tango museums: Museo Casa Carlos Gardel or Museo Mundial del Tango. -

São Paulo a Tale of Two Cities

cities & citizens series bridging the urban divide são paulo a tale of two cities Study cities & citizens series bridging the urban divide são paulo a tale of two cities Image: Roberto Rocco - [email protected] iv cities & citizens series - bridging the urban divide Copyright © United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT), 2010 São Paulo: A Tale of Two Cities All rights reserved UNITED NATIONS HUMAN SETTLEMENTS PROGRAMME P.O. Box 30030, GPO, Nairobi, 00100, Kenya Tel.: +254 (20) 762 3120, Fax: +254 (20) 762 4266/4267/4264/3477/4060 E-mail: [email protected] www.unhabitat.org DISCLAIMER The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries or regarding its economic system or degree of development. The analysis, conclusions and recommendations of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT), the Governing Council of UN-HABITAT or its Member States.Excerpts may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. HS Number: HS/103/10E ISBN Number:(Volume) 978-92-1-132214-9 ISBN Number(Series): 978-92-1-132029-9 This book was prepared under the overall guidance of the Director of MRD, Oyebanji Oyeyinka and the direct coordination of Eduardo Moreno, Head of City Monitoring Branch. The book primarily uses data prepared by the São Paulo-based, Fundação Sistema Estadual de Análise de Dados (SEADE) in collaboration with UN-HABITAT under the technical coordination of Gora Mboup, Chief of the Global Urban Observatory . -

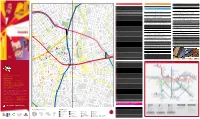

Metro: the Best Way to Know São Paulo

Metro: the best way to know São Paulo There is no better option than the Metro to visit the countless tourist sites in the largest city in Brazil – and one of the largest in the world. Note: many attractions can be reached on a single metro ride. For more distant locations, metro integrated bus lines are available. Running 74.3 kilometers of rail through 64 stations, the São Paulo metro is your best bet for getting to the host of tourist and cultural attractions located throughout this sprawling metropolis. Some of these locations, including Paulista and Liberdade Avenues ("the Eastern district"), can be accessed directly by metro. Other more distant destinations, such as the Zoo and Carmo Park, can be reached by using one of the many metro integrated bus lines. 1 Line-Blue: riders have access to the Imigrantes Expo Center, the Botanic Garde, the São Paulo Cultural Center, the Banco do Brasil Cultural Center, the Sacred Art Museu, the Portuguese Langar Art Museum, 25 de Março Street, the Japanese Immigrant Museum, the São Paulo State Art Gallery São Paulo See Metropolitan Cathedral, the Samba Boulevard and Anhembi Park. 2 Line-Green: visitors can tour the Itaú Cultural Institute, the São Paulo Art Museum (MASP), the Casa das Rosas, the Jewish Cultural Center, Ipiranga Museum, the São Paulo Aquarium and the Football Museum, an annex of Pacaembu Stadium. 3 Line-Red: riders can visit the Latin American Memorial, Água Branca Park, Carmo Park, and the Immigrants Memorial. 5 Line-Violet: the main attraction along this line is Santo Amaro Station, the first metro line station built under a cable stayed bridge, which spans the Pinheiros River. -

O Projeto Paisagístico Dos Jardins Públicos Do Recife De 1872 a 1937

..................................................................... UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE PERNAMBUCO – UFPE CENTRO DE ARTES E COMUNICAÇÃO – CAC DEPARTAMENTO DE ARQUITETURA E URBANISMO – DAU PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM DESENVOLVIMENTO URBANO – MDU O projeto paisagístico dos jardins públicos do Recife de 1872 a 1937 Aline de Figueirôa Silva Recife, abril de 2007. ..................................................................... UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE PERNAMBUCO – UFPE CENTRO DE ARTES E COMUNICAÇÃO – CAC DEPARTAMENTO DE ARQUITETURA E URBANISMO – DAU PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM DESENVOLVIMENTO URBANO – MDU O projeto paisagístico dos jardins públicos do Recife de 1872 a 1937 Aline de Figueirôa Silva Orientadora: Profª Drª Ana Rita Sá Carneiro Co-orientador: Profº Drº Denis Bernardes Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-graduação em Desenvolvimento Urbano da Universidade Federal de Pernambuco (MDU/UFPE) como um dos requisitos para obtenção do título de Mestre em Desenvolvimento Urbano. Recife, abril de 2007. A Iracema (93), Dionéa (57), Amanda (28), e Clara (0), avó, mãe, irmã e sobrinha: quatro gerações que representam de onde aprendi e a quem poderei deixar alguma perspectiva de zelo pelo antigo e amor aos jardins. Agradecimentos Apesar da condição de pesquisa de mestrado, não faltaram a este trabalho razões de ordem pessoal e afetiva, as quais, no entanto, não lhe eximem da busca constante pelo rigor metodológico. Ao contrário, foram (e serão) questões essas que alimentaram a elaboração desta dissertação, por acreditar que a produção verdadeira do conhecimento (e não do conhecimento verdadeiro) se consubstancia na sua capacidade transformadora. O envolvimento com o tema, que se tornou certo compromisso e opção profissional, se iniciou nos tempos de pesquisa no Laboratório da Paisagem/UFPE em fevereiro de 2001, seja como voluntária ou bolsista de iniciação científica do PIBIC/CNPq, seja por ocasião do trabalho de graduação em Arquitetura e Urbanismo, concluído em 2004.