Perception, Misperception and Surprise in the Yom Kippur War: a Look at the New Evidence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Israel: What Went Wrong on October 6?: the Partial Report of the Israeli Commission of Inquiry Into the October War Source: Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol

Israel: What Went Wrong on October 6?: The Partial Report of the Israeli Commission of Inquiry into the October War Source: Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 3, No. 4 (Summer, 1974), pp. 189-207 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the Institute for Palestine Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2535473 . Accessed: 09/03/2015 16:05 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press and Institute for Palestine Studies are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Palestine Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 66.134.128.11 on Mon, 9 Mar 2015 16:05:41 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions SPECIAL DOCUMENT ISRAEL: WHAT WENT WRONG ON OCTOBER 6 ? THE PARTIAL REPORT OF THE ISRAELI COMMISSION OF INQUIRY INTO THE OCTOBER WAR [This was officiallyissued in Israel on April 2, 1974 as a reporton the mostpressing issuesraised duringthe generalinvestigation by the AgranatCommission of the prepared- ness of Israel for the October War. It comprisesa preface on the terms of reference and proceduresof the Committee(below); an account of the evaluationsmade by the Israeli IntelligenceServices up to October 6 (p. -

ISRAEL's TRUTH-TELLING WITHOUT ACCOUNTABILITY Inquest Faults

September 1991 IIISRAEL'''S TTTRUTH---T-TTTELLING WITHOUT AAACCOUNTABILITY Inquest Faults Police in Killings at Jerusalem HolyHoly Site But Judge Orders No Charges Table of Contents I. Introduction........................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 II. The Confrontation: Sequence of Events............................................................................................................................................................ 6 III. Judge Kama's Findings on Police Conduct.................................................................................................................................................... 8 IV. The Case for Prosecution ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 12 I. Introduction Middle East Watch commends the extensive investigation published by Israeli Magistrate Ezra Kama on July 18 into the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif killings. However, Middle East Watch is disturbed that, in light of evidence establishing criminal conduct by identifiable police officers, none of the officers involved in the incident has been prosecuted or disciplined. Middle East Watch also believes that the police's criminal investigation of the incident last fall was grossly negligent and in effect sabotaged the -

The Labor Party and the Peace Camp

The Labor Party and the Peace Camp By Uzi Baram In contemporary Israeli public discourse, the preoccupation with ideology has died down markedly, to the point that even releasing a political platform as part of elections campaigns has become superfluous. Politicians from across the political spectrum are focused on distinguishing themselves from other contenders by labeling themselves and their rivals as right, left and center, while floating around in the air are slogans such as “political left,” social left,” “soft right,” “new right,” and “mainstream right.” Yet what do “left” and “right” mean in Israel, and to what extent do these slogans as well as the political division in today’s Israel correlate with the political traditions of the various parties? Is the Labor Party the obvious and natural heir of The Workers Party of the Land of Israel (Mapai)? Did the historical Mapai under the stewardship of Ben Gurion view itself as a left-wing party? Did Menachem Begin’s Herut Party see itself as a right-wing party? The Zionist Left and the Soviet Union As far-fetched as it may seem in the eyes of today’s onlooker, during the first years after the establishment of the state, the position vis-à-vis the Soviet Union was the litmus test of the left camp, which was then called “the workers’ camp.” This camp viewed the centrist liberal “General Zionists” party, which was identified with European liberal and middle-class beliefs in private property and capitalism, as its chief ideological rival (and with which the heads of major cities such as Tel Aviv and Ramat Gan were affiliated). -

The Development of Security-Military Thinking in The

The Development of Security-Military Thinking in the IDF Gabi Siboni, Yuval Bazak, and Gal Perl Finkel In the seven weeks between August 26 and October 17, 1953, Ben-Gurion spent his vacation holding the “seminar,” 1 following which the State of Israel’s security concept was formulated, along with the key points in the IDF doctrine.2 Ben-Gurion, who had been at the helm of the defense establishment for the Israeli population since the 1930s, argued that he needed to distance himself from routine affairs in order to scrutinize and re-analyze defense strategies. Ben-Gurion understood that Israel would be fighting differently during the next war – against countries, and not against Israeli Arabs 3 – and that the means, the manpower, and the mindset of the Haganah forces did not meet the needs of the future. This prompted him to concentrate on intellectual efforts, which led to the formulation of an approach that could better contend with the challenges of the future. This was only the starting point in the development and establishment of original and effective Israeli military thinking. This thinking was at the core of the building and operation of military and security strength under inferior conditions, and it enabled the establishment of the state and the nation, almost against all odds. The security doctrine that Ben-Gurion devised was based on the idea of achieving military victory in every confrontation. During a time when the Jewish population was 1.2 million and vying against countries whose populations totaled about 30 million, this was a daring approach, bordering on the impossible. -

Hard Lessons in the Holy Land

Hard Lessons in the Holy Land Joint Fire Support in the Yom Kippur War By Jimmy McNulty On October 6 th , 1973, a coalition of Arab states led by Egypt and Syria launched a surprise attack against Israel in the Sinai Peninsula and the Golan Heights. This would spark what would become known as the Yom Kippur War, and would threaten Israel’s very existence. Although it was a brief conflict, the Yom Kippur War would forever transform the Middle East, and would have lasting global impacts. Its military significance is often overshadowed by the concurrent Vietnam War, and is often not afforded the thorough analysis it deserves. The Yom Kippur War would see the introduction of new tactics and technologies that would change how conflicts are fought, and would provide a number of sobering lessons to all participants. The focus of this essay will be on joint fire support, analysing how each of the participants employed their fire support assets, the impact their fire support assets had on operations, and the lessons learned that can be applied to Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) operations. Prior to examining the actual conduct of the Yom Kippur War, it is necessary to outline a number of key concepts regarding joint operations. Joint operations involve two or more military environments (army, navy, air force) working together to plan and execute operations, rather than working separately. 1 Joint operations require interoperability and synchronization between the different military environments under the command of a single Joint Task Force (JTF) commander in order to maximize the effectiveness and efficiency of the force. -

1 Israel Studies, 8:1, Spring 2003 INTERVIEW with ABBA EBAN, 11

1 Israel Studies, 8:1, Spring 2003 INTERVIEW WITH ABBA EBAN, 11 MARCH 1976 Avi Shlaim INTRODUCTION Abba Eban was often referred to as the voice of Israel. He was one of Israel’s most brilliant, eloquent, and skillful representatives abroad in the struggle for independence and in the first 25 years of statehood. He was less effective in the rough and tumble of Israeli domestic politics because he lacked the common touch and, more importantly, because he lacked a power base of his own. Nevertheless, he played a major role in the formulation and conduct of Israel’s foreign policy during a crucial period in the country’s history. Born in South Africa, on 2 February 1915, Eban grew up in London and gained a degree in Oriental languages from Cambridge University. During the Second World War he served with British military intelligence in Cairo and Jerusalem and reached the rank of major. After the war he joined the political department of the Jewish Agency. In 1949 he became head of the Israeli delegation to the United Nations. The following year he was appointed ambassador to the United States and he continued to serve in both posts until 1959. On his return to Israel, Eban was elected to the Knesset on the Mapai list and kept his seat until 1988. He joined the government in 1960 as minister without portfolio and later became minister of education and culture. Three years later he was promoted to the post of deputy by Prime Minister Levi Eshkol. In 1966 Eban became foreign minister and he retained this post after Golda Meir succeeded Levi Eshkol in 1969. -

Palestinian Groups

1 Ron’s Web Site • North Shore Flashpoints • http://northshoreflashpoints.blogspot.com/ 2 Palestinian Groups • 1955-Egypt forms Fedayeem • Official detachment of armed infiltrators from Gaza National Guard • “Those who sacrifice themselves” • Recruited ex-Nazis for training • Fatah created in 1958 • Young Palestinians who had fled Gaza when Israel created • Core group came out of the Palestinian Students League at Cairo University that included Yasser Arafat (related to the Grand Mufti) • Ideology was that liberation of Palestine had to preceed Arab unity 3 Palestinian Groups • PLO created in 1964 by Arab League Summit with Ahmad Shuqueri as leader • Founder (George Habash) of Arab National Movement formed in 1960 forms • Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) in December of 1967 with Ahmad Jibril • Popular Democratic Front for the Liberation (PDFLP) for the Liberation of Democratic Palestine formed in early 1969 by Nayif Hawatmah 4 Palestinian Groups Fatah PFLP PDFLP Founder Arafat Habash Hawatmah Religion Sunni Christian Christian Philosophy Recovery of Palestine Radicalize Arab regimes Marxist Leninist Supporter All regimes Iraq Syria 5 Palestinian Leaders Ahmad Jibril George Habash Nayif Hawatmah 6 Mohammed Yasser Abdel Rahman Abdel Raouf Arafat al-Qudwa • 8/24/1929 - 11/11/2004 • Born in Cairo, Egypt • Father born in Gaza of an Egyptian mother • Mother from Jerusalem • Beaten by father for going into Jewish section of Cairo • Graduated from University of King Faud I (1944-1950) • Fought along side Muslim Brotherhood -

The Mental Cleavage of Israeli Politics

Israel Affairs ISSN: 1353-7121 (Print) 1743-9086 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fisa20 The mental cleavage of Israeli politics Eyal Lewin To cite this article: Eyal Lewin (2016) The mental cleavage of Israeli politics, Israel Affairs, 22:2, 355-378, DOI: 10.1080/13537121.2016.1140352 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13537121.2016.1140352 Published online: 04 Apr 2016. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fisa20 Download by: [Ariel University], [Eyal Lewin] Date: 04 April 2016, At: 22:06 ISRAEL AFFAIRS, 2016 VOL. 22, NO. 2, 355–378 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13537121.2016.1140352 The mental cleavage of Israeli politics Eyal Lewin Department of Middle Eastern Studies and Political Science, Ariel University, Ariel, Israel ABSTRACT In societies marked by numerous diversities, like the Jewish-Israeli one, understanding social cleavages might show a larger picture of the group and form a broader comprehension of its characteristics. Most studies concentrate on somewhat conventional cleavages, such as the socioeconomic cleavage, the ethnic cleavage, the religious or the political one; this article, by contrast, suggests a different point of view for the mapping of social cleavages within Israeli society. It claims that the Jewish population in Israel is split into two competing groups: stakeholders versus deprived. These categories of social identity are psychological states of mind in which no matter how the national resources are distributed, the stakeholders will always act as superiors, even if they are in inferior positions, while the deprived will always take the role of eternal underdog even if all of the major political ranks come under their control. -

Israel's Use of Sports for Nation Branding and Public Diplomacy

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2018 ISRAEL'S USE OF SPORTS FOR NATION BRANDING AND PUBLIC DIPLOMACY Yoav Dubinsky University of Tennessee, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation Dubinsky, Yoav, "ISRAEL'S USE OF SPORTS FOR NATION BRANDING AND PUBLIC DIPLOMACY. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2018. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/4868 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Yoav Dubinsky entitled "ISRAEL'S USE OF SPORTS FOR NATION BRANDING AND PUBLIC DIPLOMACY." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Kinesiology and Sport Studies. Lars Dzikus, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Robin L. Hardin, Sylvia A. Trendafilova, Candace L. White Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) ISRAEL’S USE OF SPORTS FOR NATION BRANDING AND PUBLIC DIPLOMACY A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Yoav Dubinsky May 2018 Copyright © 2018 by Yoav Dubinsky All rights reserved. -

Shamgar Commission Report on the Assassination of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin March 28, 1996 Translation of Commission Findings by Roni Eshel Sources: See Below

Shamgar Commission Report on the Assassination of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin March 28, 1996 Translation of Commission findings by Roni Eshel Sources: see below Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated on November 4, 1995. Four days later the Israeli Government appointed a special Commission of Inquiry to investigate events surrounding the assassination. President of the Supreme Court Meir Shamgar chaired the Commission that also included two other members, General (Res.) Zvi Zamir and Professor Ariel Rosen-Zvi. The Commission started its work on November 19, 1995, finally issuing its conclusions and recommendations on March 28, 1996. Political Background to the Assassination On September 13, 1993, the Oslo Accords were officially signed on the White House lawn with the participation of President Bill Clinton, Yitzhak Rabin and Chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) Yasser Arafat. Rabin, though not enamored with Yasir Arafat or the PLO, believed it was necessary to provide some international support for the PLO in its rising competition with Hamas. Rabin feared that the Palestinians were slowly being influenced by Iran and particularly radical Islamic militancy. He believed that it was better for Israel to reach some kind of accommodation with the secular element of the Palestinian leadership and, if possible, truncate the status of Hamas. The signing of the Accords and subsequent agreements between Israel and the PLO led to heated political debates in Israel about the future of the territories that Israel secured in the June 1967 War. A significant number of Palestinians despised Arafat for signing an agreement with the country that he had vowed to destroy for most of his life; Hamas and others considered Arafat a traitor to their cause to liberate all of Palestine. -

Principles of the Israeli Political-Military Discourse Based on the Recent IDF Strategy Document

Principles of the Israeli Political-Military Discourse Based on the Recent IDF Strategy Document Kobi Michael and Shmuel Even Relations between the military and political echelons in Israel are complex and multifaceted, both in theory and in practice. The problems resulting from the interface between the two have at times resulted in ineffective military deployment or a crisis of expectations. Moreover, as the positions of the political echelon are never unanimous, its directives to the military have not always been aligned with the government’s position, and sometimes even have been nebulous. In August 2015, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) released a document entitled the “IDF Strategy” directly addressing the issue. Signed by the chief of staff, the document is notable in part for its proposal to adjust the discourse between the military and political echelons as well as to clarify the role of the chief of staff and his functional autonomy. In this document, the chief of staff suggests to the political echelon how it should formulate directives to the military so that military action will match the political objective in question, and thereby prevent a crisis of expectations. According to the document, the IDF sees its role of achieving “victory,” which does not necessarily mean defeating the enemy; the political echelon together with the chief of staff must define the concept of victory before the military is deployed. The publication of the “IDF Strategy,” unprecedented in Israel’s civil-military relations, also highlights the chief of staff’s sensitivity to Israeli public opinion. Keywords: IDF, civil-military relations, strategy, discourse space, learning, civil control Dr. -

Missing Signal

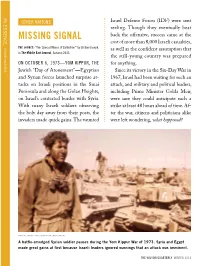

N ESSENCE I OTHER NATIONS Israel Defense Forces (IDF) were sent reeling. Though they eventually beat MISSING SIGNAL back the offensive, success came at the cost of more than 8,000 Israeli casualties, OTHER NATIONS THE SOURCE: “The ‘Special Means of Collection’” by Uri Bar-Joseph, in The Middle East Journal, Autumn 2013. as well as the confident assumption that the still-young country was prepared ON OCTOBER 6, 1973—YOM KIPPUR, THE for anything. Jewish “Day of Atonement”—Egyptian Since its victory in the Six-Day War in and Syrian forces launched surprise at- 1967, Israel had been waiting for such an tacks on Israeli positions in the Sinai attack, and military and political leaders, Peninsula and along the Golan Heights, including Prime Minister Golda Meir, on Israel’s contested border with Syria. were sure they could anticipate such a With many Israeli soldiers observing strike at least 48 hours ahead of time. Af- the holy day away from their posts, the ter the war, citizens and politicians alike invaders made quick gains. The vaunted were left wondering, what happened? MANUEL LITRAN / PARIS MATCH VIA GETTY IMAGES A battle-smudged Syrian soldier pauses during the Yom Kippur War of 1973. Syria and Egypt made great gains at first because Israeli leaders ignored warnings that an attack was imminent. THE WILSON QUARTERLY WINTER 2014 N ESSENCE I an Israeli strike deep into Egypt. The The military intelligence Agranat Commission’s conclusions led chief never informed to the dismissal of the IDF’s chief of staff, David Elazar, and the head of OTHER NATIONS his superiors that he Aman, Major General Eli Zeira.