Chapter I Introduction the Methodology of Starting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ed 393 216 Author Title Report No Pub Date Available From

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 393 216 EA 027 482 AUTHOR Scribner, Jay D., Ed.; Layton, Donald H., Ed. TITLE The Study of Educational Politics. 1994 Commemorative Yearbook of the Politics of Education Association (1969-1994). Education Policy Perspectives Series. REPORT NO ISBN-0-7507-0419-5 PUB DATE 95 NOTE 225p. AVAILABLE FROM Falmer Press, Taylor & Francis, Inc., 1900 Frost Road, Suite 101, Bristol, PA 19007 (paperback: ISBN-0-7507-0419-5; clothbound: ISBN-0-7507-0418-7). PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Educational Principles; Educational Sociology; Elementary Secondary Education; Feminism; Ideology; International Education; *Policy Analysis; *Policy Formation; Political Influences; *Politics of Education; Role of Education; Values ABSTRACT This book surveys major trends in the politics of education over the last 25 years. Chapters synthesize political and policy developments at local, national, and state levels in the United States, as well as in the international arena. The chapters examine the emerging micropolitics of education and policy-analysis, cultural, and feminist studies. The foreword is by Paul E. Peterson and the introduction by Jay D. Scribner and Donald H.Layton. Chapters include:(1) "Values: The 'What?' of the Politics of Education" (Robert T. Stout, Marilyn Tallerico, and Kent Paredes Scribner) ;(2) "The Politics of Education: From Political Science to Interdisciplinary Inquiry" (Kenneth K. Wong);(3) "The Crucible of Democracy: The Local Arena" (Laurence Iannaccone and Frank W.Lutz); (4) "State Policymaking and School Reform: Influences and Influentials" (Tim L. Mazzoni);(5) "Politics of Education at the Federal Level" (Gerald E. Sroufe) ;(6) "The International Arena: The Global Village" (Frances C. -

The Politics of Group Representation Quotas for Women and Minorities Worldwide Mona Lena Krook and Diana Z

The Politics of Group Representation Quotas for Women and Minorities Worldwide Mona Lena Krook and Diana Z. O’Brien In recent years a growing number of countries have established quotas to increase the representation of women and minorities in electoral politics. Policies for women exist in more than one hundred countries. Individual political parties have adopted many of these provisions, but more than half involve legal or constitutional reforms requiring that all parties select a certain proportion of female candidates.1 Policies for minorities are present in more than thirty countries.2 These measures typically set aside seats that other groups are ineligible to contest. Despite parallels in their forms and goals, empirical studies on quotas for each group have developed largely in iso- lation from one another. The absence of comparative analysis is striking, given that many normative arguments address women and minorities together. Further, scholars often generalize from the experiences of one group to make claims about the other. The intuition behind these analogies is that women and minorities have been similarly excluded based on ascriptive characteristics like sex and ethnicity. Concerned that these dynamics undermine basic democratic values of inclusion, many argue that the participation of these groups should be actively promoted as a means to reverse these historical trends. This article examines these assumptions to explore their leverage in explaining the quota policies implemented in national parliaments around the world. It begins by out- lining three normative arguments to justify such measures, which are transformed into three hypotheses for empirical investigation: (1) both women and minorities will re- ceive representational guarantees, (2) women or minorities will receive guarantees, and (3) women will receive guarantees in some countries, while minorities will receive them in others. -

Rethinking Representation Author(S): Jane Mansbridge Source: the American Political Science Review, Vol

Rethinking Representation Author(s): Jane Mansbridge Source: The American Political Science Review, Vol. 97, No. 4 (Nov., 2003), pp. 515-528 Published by: American Political Science Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3593021 . Accessed: 16/08/2013 04:49 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. American Political Science Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The American Political Science Review. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 88.119.17.198 on Fri, 16 Aug 2013 04:49:00 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions American Political Science Review Vol. 97, No. 4 November 2003 Rethinking Representation JANE MANSBRIDGE Harvard University long withthe traditional"promissory" form of representation,empirical political scientists have recently analyzed several new forms, called here "anticipatory,""gyroscopic," and "surrogate" representation. None of these more recently recognized forms meets the criteria for democratic accountability developed for promissory representation, yet each generates a set of normative criteria by which it can be judged. These criteria are systemic, in contrast to the dyadic criteria appropriate for promissory representation. They are deliberative rather than aggregative. -

Nlrcv20201.Pdf

1 2020 Nancy Lipton Rosenblum Senator Joseph S. Clark Professor of Ethics in Politics and Government, Emerita Harvard University Department of Government 1731 Cambridge St. Harvard University Cambridge, MA 02138 [email protected] Educational Background B.A., Radcliffe College, Social Studies, 1969 Ph.D., Harvard University Political Science, 1973 Teaching Positions Chair, Department of Government, Harvard University, 2004-2010 Senator Joseph S. Clark Professor of Ethics in Politics and Government, 2001 to 2016 Faculty Fellow, Safra Center for Ethics, Harvard University, 2003-4 Henry Merritt Wriston Professorship, Brown University, 1997- 2001 Chairperson, Political Science Department, Brown University, 1989-95 Professor, Brown University, 1980-2000 Liberal Arts Fellow, Harvard Law School, 1992-93 Fellow, Bunting Institute, Radcliffe College, 1988-89 Visiting Professor, Harvard University, Department of Government, Fall, 1985 Associate Professor, Department of Government, Harvard University, 1977-80 Henry LaBarre Jayne Assistant Professor, Department of Government, Harvard University, 1973-77 Publications Books A Lot of People are Saying: The New Conspiracism and the Assault on Democracy”, with Russell Muirhead (Princeton University Press, 2019) 2 Good Neighbors: The Democracy of Everyday Life in America (Princeton University Press, 2016) On the Side of the Angels: An Appreciation of Parties and Partisanship (Princeton University Press, 2008) Membership and Morals: The Personal Uses of Pluralism in America (Princeton University -

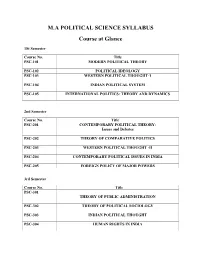

M.A POLITICAL SCIENCE SYLLABUS Course at Glance

M.A POLITICAL SCIENCE SYLLABUS Course at Glance 1St Semester Course No. Title PSC-101 MODERN POLITICAL THEORY PSC-102 POLITICAL IDEOLOGY PSC-103 WESTERN POLITICAL THOUGHT-1 PSC-104 INDIAN POLITICAL SYSTEM PSC-105 INTERNATIONAL POLITICS: THEORY AND DYNAMICS 2nd Semester Course No. Title PSC-201 CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL THEORY: Issues and Debates PSC-202 THEORY OF COMPARATIVE POLITICS PSC-203 WESTERN POLITICAL THOUGHT -II PSC-204 CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL ISSUES IN INDIA PSC-205 FOREIGN POLICY OF MAJOR POWERS 3rd Semester Course No. Title PSC-301 THEORY OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION PSC-302 THEORY OF POLITICAL SOCIOLOGY PSC-303 INDIAN POLITICAL THOUGHT PSC-304 HUMAN RIGHTS IN INDIA PSC-305 INDIA IN WORLD AFFAIRS 4th Semester Course No. Title PSC-401 CHANGING DIMENSIONS OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION IN INDIA PSC-402 INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZIATION AND ADMINISTRIATION PSC-403 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY PSC-404 COMPUTER BASICS: THEORY AND PRACTICE Elective CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL THOUGHT PSC-405 (i) 405 (ii) LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN INDIA 405 (iii) ETHICS AND POLITICS 405 (iv) COMPARATIVE FEDERALISM 405 (v) SOCIAL EXCLUSION IN INDIA Courses of Studies for M.A. in Political Science (Under Semester System of Teaching & Examination Effective from the Academic Session 2016-17) SEMESTER-I Course No. PSC-101 MODERN POLITICAL THEORY Unit-I (i) Political Theory- Evolution, The Traditional Approach; Nature and Scope of Traditional Political Theory; Prime Concerns. (ii) Modern Political Theory- Genesis and Evolution; The Modern Behavioural Approach; Nature and Scope of Modern Political Theory; Prime Concerns. Unit-II (i) Political Decision-making Theory of Harold. D. Laswell – The Concept of Politics as the Societal Decision-making Process; Classification of Societal Values; Role of Elites in the Societal Decision-making Process; Effectiveness and Legitimacy of the Societal Decision-making Structure. -

Political Education in the Elementary School: a Decision-Making Rationale

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 70-6748 COG AN, John Joseph, 1942- POLITICAL EDUCATION IN THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL: A DECISION-MAKING RATIONALE. The Ohio State U niversity, Ph.D., 1969 Education, theory and practice University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan (£) Copyright by John Joseph Cogan ,1970 POLITICAL EDUCATION IN THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL: A DECISION-MAKING RATIONALE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By John Joseph Cogan, B.S., M.A, ****** The Ohio State University 1969 Approved by College of Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This writer would like to extend hiB appreciation to all who provided guidance and help in any manner during the completion of this study. The writer is indebted immeasurably to his adviser, Professor Raymond H. Muessig, whose patient and continuous counsel made the completion of this study possible. Appreciation is also extended to Professors Robert E. Jewett and Alexander Frazier who served as readers of the dissertation. Finally, the writer is especially grateful to his wife, Norma, and hiB daughter, Susan, whose patience and understanding have been unfailing throughout the course of this study. ii VITA May 30, 19^2 . Born - Youngstown, Ohio 1 9 6 3. B.S., Kent State University, Kent, Ohio 1963-1965.... Elementary Teacher, Columbus Public Schools, Columbus, Ohio I965 ............ M.A., The Ohio State University, ColumbuB, Ohio 1965-1966 .... Graduate Assistant, College of Education, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1966-1967 .... United States Office of Education Fellow, Washington, D.C. Summer, 1967 . Acting Director, Consortium of Professional Associations for the Study of Special Teacher Improvement Programs (CONPASS), Washington, D.C. -

Patterns of Democracy This Page Intentionally Left Blank PATTERNS of DEMOCRACY

Patterns of Democracy This page intentionally left blank PATTERNS OF DEMOCRACY Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries SECOND EDITION AREND LIJPHART First edition 1999. Second edition 2012. Copyright © 1999, 2012 by Arend Lijphart. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the US Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected] (US offi ce) or [email protected] (UK offi ce). Set in Melior type by Integrated Publishing Solutions, Grand Rapids, Michigan. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lijphart, Arend. Patterns of democracy : government forms and performance in thirty-six countries / Arend Lijphart. — 2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-17202-7 (paperbound : alk. paper) 1. Democracy. 2. Comparative government. I. Title. JC421.L542 2012 320.3—dc23 2012000704 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992 (Permanence of Paper). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 for Gisela and for our grandchildren, Connor, Aidan, Arel, Caio, Senta, and Dorian, in the hope that the twenty-fi rst century—their century—will yet become more -

SS 12 Paper V Half 1 Topic 1B

Systems Analysis of David Easton 1 Development of the General Systems Theory (GST) • In early 20 th century the Systems Theory was first applied in Biology by Ludwig Von Bertallanfy. • Then in 1920s Anthropologists Bronislaw Malinowski ( Argonauts of the Western Pacific ) and Radcliffe Brown ( Andaman Islanders ) used this as a theoretical tool for analyzing the behavioural patterns of the primitive tribes. For them it was more important to find out what part a pattern of behaviour in a given social system played in maintaining the system as a whole, rather than how the system had originated. • Logical Positivists like Moritz Schilick, Rudolf Carnap, Otto Von Newrath, Victor Kraft and Herbert Feigl, who used to consider empirically observable and verifiable knowledge as the only valid knowledge had influenced the writings of Herbert Simon and other contemporary political thinkers. • Linguistic Philosophers like TD Weldon ( Vocabulary of Politics ) had rejected all philosophical findings that were beyond sensory verification as meaningless. • Sociologists Robert K Merton and Talcott Parsons for the first time had adopted the Systems Theory in their work. All these developments in the first half of the 20 th century had impacted on the application of the Systems Theory to the study of Political Science. David Easton, Gabriel Almond, G C Powell, Morton Kaplan, Karl Deutsch and other behaviouralists were the pioneers to adopt the Systems Theory for analyzing political phenomena and developing theories in Political Science during late 1950s and 1960s. What is a ‘system’? • Ludwig Von Bertallanfy: A system is “a set of elements standing in inter-action.” • Hall and Fagan: A system is “a set of objects together with relationships between the objects and between their attributes.” • Colin Cherry: The system is “a whole which is compounded of many parts .. -

American Political Science Review

AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW AMERICAN https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000060 . POLITICAL SCIENCE https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms REVIEW , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at 08 Oct 2021 at 13:45:36 , on May 2018, Volume 112, Issue 2 112, Volume May 2018, University of Athens . May 2018 Volume 112, Issue 2 Cambridge Core For further information about this journal https://www.cambridge.org/core ISSN: 0003-0554 please go to the journal website at: cambridge.org/apsr Downloaded from 00030554_112-2.indd 1 21/03/18 7:36 AM LEAD EDITOR Jennifer Gandhi Andreas Schedler Thomas König Emory University Centro de Investigación y Docencia University of Mannheim, Germany Claudine Gay Económicas, Mexico Harvard University Frank Schimmelfennig ASSOCIATE EDITORS John Gerring ETH Zürich, Switzerland Kenneth Benoit University of Texas, Austin Carsten Q. Schneider London School of Economics Sona N. Golder Central European University, and Political Science Pennsylvania State University Budapest, Hungary Thomas Bräuninger Ruth W. Grant Sanjay Seth University of Mannheim Duke University Goldsmiths, University of London, UK Sabine Carey Julia Gray Carl K. Y. Shaw University of Mannheim University of Pennsylvania Academia Sinica, Taiwan Leigh Jenco Mary Alice Haddad Betsy Sinclair London School of Economics Wesleyan University Washington University in St. Louis and Political Science Peter A. Hall Beth A. Simmons Benjamin Lauderdale Harvard University University of Pennsylvania London School of Economics Mary Hawkesworth Dan Slater and Political Science Rutgers University University of Chicago Ingo Rohlfi ng Gretchen Helmke Rune Slothuus University of Cologne University of Rochester Aarhus University, Denmark D. -

American Political Science Association

A MERICAN P OLITICAL S CIENCE ASSOCIATION Assessing (In)Security after the Arab Spring John Gledhill, guest editor, April Longley Alley, Brian McQuinn, and Mohammad Ayatollahi Tabaar Misconceptions and Realities of the 2011 Tunisian Election Moez Habadou and Nawel Amrouche Political Science & Politics Katrina Seven Years On PSO CTOBER 2013, V OLUME 46, N UMBER 4 Christine L. Day American Political Science Association Make plans to attend the 2014 APSA Teaching & Learning Conference The 2014 APSA Teaching & Learning Conference theme is “Teaching Inclusively: Inte- grating Multiple Approaches into the Curriculum.” In this unique meeting, APSA strives to promote the greater understanding of cutting- edge approaches, techniques, and methodologies for the political science classroom. Using a working group format, the conference includes plenaries, tracks, and work- shops on topics such as: t Civic Engagement t Integrating Technology in the t Conflict and Conflict Resolution Classroom t Core Curriculum/General t Internationalizing the Curriculum Education t Teaching and Learning at Community t Curricular and Program Assessment Colleges t Distance Learning t Professional Development t Diversity, Inclusiveness, and Equality t Simulations and Role Play t Graduate Education: Teaching and t Teaching Political Theory and Theories Advising Graduate Students t Teaching Research Methods www.apsanet.org/teachingconference 1527 New Hampshire Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20036 | 202.483.2512 | www.apsanet.org ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Hasidic Public Schools in Kiryas Joel

The Draw and Drawbacks of Religious Enclaves in a Constitutional Democracy: Hasidic Public Schools in Kiryas Joel JUDITH LYNN FAILER' INTRODUCTION Recent work in political and constitutional studies has celebrated the salutary effects of robust civil societies for democracies.' Robert Putnam, for example, has described how Italian communities with stronger civic traditions have political leaders who are less "elitist" and are "more enthusiastic supporters of political equality" while their citizens' political involvement is characterized by "greater social trust and greater confidence in the law-abidingness of their fellow citizens than... citizens in the least civic regions."' William Galston makes a case for how civic organizations in civil society can foster the development of liberal virtues Jean L. Cohen and Andrew Arato have argued that civil society is "the primary locus for the potential expansion of democracy under 'really existing' liberal-democratic regimes." 4 * Assistant Professor of Political Science and American Studies, Indiana University-Bloomington. Prepared for presentation at a symposium on Civil Society, Indiana University School of Law, March 29, 1996. Thank you to Fred Aman and Steve Conrad for their generous invitation. I am grateful to Jane Mansbridge for helping me think through the ways by which Kiryas Joel poses particular challenges in democratic theory as an enclave group. Thank you also to Mark Brandon, Dana Chabot, David Orentlicher, and Jean Robinson for helpful conversations in preparation of this article, and to Jeffrey Isaac and Sanford Levinson for their suggestions for revisions. 1. For the purposes of this paper, Iam following John Gray's definition of "civil society" as "that sphere of autonomous institutions, protected by a rule of law, within which individuals and communities possessing divergent values and beliefs may coexist in peace." JOHN GRAY, POST LIBERALISM: STUDIES IN POLITICAL THOUGHT 157 (1993). -

APSA Contributors AS of NOVEMBER 10, 2014

APSA Contributors AS OF NOVEMBER 10, 2014 This list celebrates the generous contributions of our members in Jacobson Paul Allen Beck giving to one or more of the following programs from 1996 through 2014: APSA awards, programs, the Congressional Fellowship Pro- Cynthia McClintock John F. Bibby gram, and the Centennial Campaign. APSA thanks these donors for Ruth P. Morgan Amy B. Bridges ensuring that the benefi ts of membership and the infl uence of the Norman J. Ornstein Michael A. Brintnall profession will extend far into the future. APSA will update and print T.J. Pempel David S. Broder this list annually in the January issue of PS. Dianne M. Pinderhughes Charles S. Bullock III Jewel L. Prestage Margaret Cawley CENTENNIAL CIRCLE Offi ce of the President Lucian W. Pye Philip E. Converse ($25,000+) Policy Studies Organization J. Austin Ranney William J. Daniels Walter E. Beach Robert D. Putnam Ben F. Reeves Christopher J. Deering Doris A. Graber Ronald J Schmidt, Sr. Paul J. Rich Jorge I. Dominguez Pendleton Herring Smith College David B. Robertson Marion E. Doro Chun-tu Hsueh Endowment Janet D. Steiger for International Scholars Catherine E. Rudder Melvin J. Dubnick and Huang Hsing Kay Lehman Schlozman Eastern Michigan University Foundation FOUNDER’S CIRCLE ($5,000+) Eric J. Scott Leon D. Epstein Arend Lijphart Tony Affi gne J. Merrill Shanks Kathleen A. Frankovic Elinor Ostrom Barbara B. Bardes Lee Sigelman John Armando Garcia Beryl A. Radin Lucius J. Barker Howard J. Silver George J. Graham Leo A. Shifrin Robert H. Bates William O. Slayman Virginia H.