PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/206026 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-09-25 and may be subject to change. 18 De Zeventiende Eeuw 31 (2015) 1, pp. 18-54 - eISSN: 2212-7402 - Print ISSN: 0921-142x Coping with crisis Career strategies of Antwerp painters after 1585 David van der Linden David van der Linden is lecturer and nwo Veni postdoctoral fellow at the University of Groningen. He recently published Experiencing Exile. Huguenot Refugees in the Dutch Repu- blic, 1680-1700 (Ashgate, 2015). His current research project explores Protestant and Catholic memories about the French civil wars. [email protected] Abstract This article explores how painters responded to the crisis on the Antwerp art market in the 1580s. Although scholarship has stressed the profound crisis and subsequent emigration wave, prosopographical analysis shows that only a mino- rity of painters left the city. Demand for Counter-Reformation artworks allowed many to pursue their career in Antwerp, while others managed to survive the crisis by relying on cheap apprentices and the export of mass-produced paintings. Emigrant painters, on the other hand, minimised the risk of migration by settling in destinations that already had close artistic ties to Antwerp, such as Middelburg. Prosopographical analysis thus allows for a more nuanced understanding of artistic careers in the Low Countries. Keywords: Antwerp painters, career strategies, art market, guild of St. -

Bruegel Notes Writing of the Novel Began October 20, 1998

Rudy Rucker, Notes for Ortelius and Bruegel, June 17, 2011 The Life of Bruegel Notes Writing of the novel began October 20, 1998. Finished first fully proofed draft on May 20, 2000 at 107,353 words. Did nothing for a year and seven months. Did revisions January 9, 2002 - March 1, 2002. Did additional revisions March 18, 2002. Latest update of the notes, September 7, 2002 64,353 Words. Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................... 1 Timeline .................................................................................................................. 9 Painting List .......................................................................................................... 10 Word Count ........................................................................................................... 12 Title ....................................................................................................................... 13 Chapter Ideas ......................................................................................................... 13 Chapter 1. Bruegel. Alps. May, 1552. Mountain Landscape. ....................... 13 Chapter 2. Bruegel. Rome. July, 1553. The Tower of Babel. ....................... 14 Chapter 3. Ortelius. Antwerp. February, 1556. The Battle Between Carnival and Lent......................................................................................................................... 14 Chapter 4. Bruegel. Antwerp. February, -

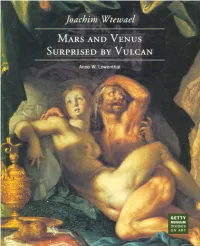

Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan

Joachim Wtewael MARS AND VENUS SURPRISED BY VULCAN Joachim Wtewael MARS AND VENUS SURPRISED BY VULCAN Anne W. Lowenthal GETTY MUSEUM STUDIES ON ART Malibu, California Christopher Hudson, Publisher Cover: Mark Greenberg, Managing Editor Joachim Wtewael (Dutch, 1566-1638). Cynthia Newman Bohn, Editor Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan, Amy Armstrong, Production Coordinator circa 1606-1610 [detail]. Oil on copper, Jeffrey Cohen, Designer 20.25 x 15.5 cm (8 x 6/8 in.). Malibu, J. Paul Getty Museum (83.PC.274). © 1995 The J. Paul Getty Museum 17985 Pacific Coast Highway Frontispiece: Malibu, California 90265-5799 Joachim Wtewael. Self-Portrait, 1601. Oil on panel, 98 x 74 cm (38^ x 29 in.). Utrecht, Mailing address: Centraal Museum (2264). P.O. Box 2112 Santa Monica, California 90407-2112 All works of art are reproduced (and photographs provided) courtesy of the owners unless otherwise Library of Congress indicated. Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lowenthal, Anne W. Typography by G & S Typesetting, Inc., Joachim Wtewael : Mars and Venus Austin, Texas surprised by Vulcan / Anne W. Lowenthal. Printed by C & C Offset Printing Co., Ltd., p. cm. Hong Kong (Getty Museum studies on art) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-89236-304-5 i. Wtewael, Joachim, 1566-1638. Mars and Venus surprised by Vulcan. 2. Wtewael, Joachim, 1566-1638 — Criticism and inter- pretation. 3. Mars (Roman deity)—Art. 4. Venus (Roman deity)—Art. 5. Vulcan (Roman deity)—Art. I. J. Paul Getty Museum. II. Title. III. Series. ND653. W77A72 1995 759-9492-DC20 94-17632 CIP CONTENTS Telling the Tale i The Historical Niche 26 Variations 47 Vicissitudes 66 Notes 74 Selected Bibliography 81 Acknowledgments 88 TELLING THE TALE The Sun's loves we will relate. -

A Landscape with a Convoy on a Wooded Track Under Attack Oil on Panel 44 X 64 Cm (17⅜ X 25¼ In)

Sebastian Vrancx (Antwerp 1573 - Antwerp 1647) A Landscape with a Convoy on a Wooded Track under Attack oil on panel 44 x 64 cm (17⅜ x 25¼ in) Sebastian Vrancx was one of the first artists in the Netherlands to attempt battle scenes and A Landscape with Convoy on a Wooded Track under Attack offers an excellent example of his work. A wagon is under attack from bandits who have been hiding in the undergrowth on the right-hand side of the painting. The wagon has stopped as its driver flees for the safety of the bushes, whilst its occupants are left stranded inside. The wagon is guarded by three soldiers on horseback but in their startled state none have managed to engage their attackers. A line of bandits emerge from their hiding place and circle behind and around their victims, thus adding further to the confusion. Two figures remain in the bushes to provide covering fire and above them, perched in a tree, is one of their companions who has been keeping watch for the convoy and now helps to direct the attack. The scene is set in a softly coloured and brightly-lit landscape, which contrasts with the darker theme of the painting. Attack of Robbers, another scene of conflict, in the Hermitage, also possesses the decorative qualities and Vrancx’s typically poised figures, just as in A Landscape with a Convoy on a Wooded Track under Attack. A clear narrative, with travellers on horses attempting to ward off robbers, creates a personal and absorbing image. It once more reveals Vrancx’s delight in detailing his paintings with the dynamic qualities that make his compositions appealing on both an aesthetic and historical level. -

MARTEN VAN CLEVE I (C. 1527 – Antwerp – Before 1581) a Wedding

VP4739 MARTEN VAN CLEVE I (c. 1527 – Antwerp – before 1581) A Wedding Procession On canvas, 61¼ X 101 ins. (155.3 X 256 cm) PROVENANCE Marchesa de Bermejillo del Rey, by the early 20th century And by descent to the previous owner Private Collection, Spain, until 2015 LITERATURE M. Diaz Padrón, ‘La Obra de Pedro Brueghel el jóven en Espana”, Archivo Espanol de Arte, 1980, p. 309, fig. 18. K. Ertz, Pieter Brueghel der Jüngere, Lingen, 2000, vol. II, p. 702, no. A830. Against a backdrop of rolling farmlands and a giant windmill, a wedding party makes its way along a road from the village on the right, where preparations are being made for the wedding feast, to the church in the upper left-hand corner. As was customary, the bride and groom walk separately, each processed by a man playing a doedelzac (bagpipes). Tall trees single out the groom, who is identified by the wedding crown he wears on top of his bright red cap. He is followed by two older men, probably the fathers of the bridal couple, and the other menfolk of the village. Then comes the plump and solemn-looking bride, wearing a bridal crown and flanked on either side by pages. She is attended by the two mothers and the other female members of the party. Work in the fields has all but stopped: three sacks of flour sit at the foot of the windmill and a cart stands idle. The workers have all turned out to accompany the wedding procession on its way: among the crowd of well-wishers are young men and old, a shepherd, a miller, his face white with flour, and many more besides. -

TRQ Layout Def 1-6 Web.Indd

The 2010 Rubenianum 2 Quarterly Rubenianum Fund gathers momentum Dear Friends of the Rubenianum, In the past few months, the Rubenianum Fund has continued to gather momentum. We are delighted to let you know that the The total amount raised so far already exceeds Euro 1.4 million from donors in results so far of the fundraising initiatives of Belgium, the United States, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, France, Spain the Rubenianum Fund have been immensely and Switzerland. This is especially gratifying in these economically diffi cult times. encouraging. Only three weeks ago, on 21th It signifi es that the fi nal target of Euro 2 million is within reach, although obviously September to be precise, our colleagues of the quite a lot of ground still needs to be covered. Rubenshuis hosted a splendid fundraising dinner for the Dutch community of patrons The next fundraising event will take place in Madrid in the premises of the and collectors living in our country which was Fundacion Carlos de Amberes. This is a most appropriate location, as the Fundacion also attended by the Dutch consul–general. was established at the end of the 16th century by a Flemish merchant who came The benevolent and generous support of a to Madrid. Moreover, it houses an impressive Rubens Altarpiece depicting Saint growing number of international Donors and Andrew in its Chapel of San Andres de los Flamencos. Benefactors made it possible to hire two talented Madrid will also be the venue for the fi rst trip for the donors and benefactors of the junior staff members on a fulltime basis. -

Büttner Antwerpener Maler

Kunstgeschichte. Open Peer Reviewed Journal www.kunstgeschichte-ejournal.net NILS BÜTTNER (STAATLICHE AKADEMIE DER BILDENDEN KÜNSTE STUTTGART ) Antwerpener Maler – zwischen Ordnung der Gilde und Freiheit der 1 Kunst Zusammenfassung Den Antwerpener Malern wurde im Unterschied zu den in anderen Ländern Europas üblichen Standards über die verpflichtenden Ausbildungsjahre hinaus kein Probestück abverlangt. Auch die Satzungen der Gilden in Brügge, Brüssel sowie in den Städten der nördlichen Provinzen sahen kein Meisterstück vor. Dennoch scheint es allgemein nicht unüblich gewesen zu sein, zum Ende der Lehrzeit eine Probe seines Könnens abzulegen oder der im Namen des hl. Lukas zusammengeschlossenen Gemeinschaft zu anderer Gelegenheit ein Gemälde zu dedizieren, das dann in den Gildehäusern seinen Ort fand. Diesen Bildern und den spezifischen Bedingungen, unter denen man die Meisterwürde der Antwerpener Malergilde erwerben konnte, ist der Text gewidmet. <1> Gegen die Anfeindungen, denen Baron Van Ertborn sich ausgesetzt sah, boten weder seine adelige Abstammung noch die Summe der vorgeschobenen Ehrentitel einen wirksamen Schutz. Er hatte den Fehler begangen, nachdem er 1805 zum Ehren-Geheimschreiber der Antwerpener Akademie für Schöne Künste ernannt worden war, seine im Archiv dieser Institution gewonnenen Erkenntnisse der gebildeten Öffentlichkeit zur Kenntnis zu bringen. 2 Die 1663 gegründete Antwerpener Akademie war aus der St. Lukasgilde der Scheldestadt hervorgegangen, deren glorreiche Tradition bis ins ferne Mittelalter zurückreichte. Aus -

On Brabant Rubbish, Economic Competition, Artistic Rivalry, And

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) On Brabant rubbish, economic competition, artistic rivalry and the growth of the market for paintings in the first decades of the seventeenth century Sluijter, E.J. Publication date 2009 Document Version Final published version Published in Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Sluijter, E. J. (2009). On Brabant rubbish, economic competition, artistic rivalry and the growth of the market for paintings in the first decades of the seventeenth century. Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art, 1(2). http://jhna.org/index.php/volume-1-issue-2/72- vol1issue2/109-on-brabant-rubbish-economic-competition-artistic-rivalry-and-the-growth-of- the-market-for-paintings-in-the-first-decades-of-the-seventeenth-century General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:30 Sep 2021 HOME VOLUME 1: ISSUE 2 PAST ISSUES SUBMISSIONS ABOUT JHNA SUPPORT JHNA CONTACT search.. -

Bodies of Knowledge: the Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2015 Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Geoffrey Shamos University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Shamos, Geoffrey, "Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600" (2015). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1128. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Abstract During the second half of the sixteenth century, engraved series of allegorical subjects featuring personified figures flourished for several decades in the Low Countries before falling into disfavor. Designed by the Netherlandsâ?? leading artists and cut by professional engravers, such series were collected primarily by the urban intelligentsia, who appreciated the use of personification for the representation of immaterial concepts and for the transmission of knowledge, both in prints and in public spectacles. The pairing of embodied forms and serial format was particularly well suited to the portrayal of abstract themes with multiple components, such as the Four Elements, Four Seasons, Seven Planets, Five Senses, or Seven Virtues and Seven Vices. While many of the themes had existed prior to their adoption in Netherlandish graphics, their pictorial rendering had rarely been so pervasive or systematic. -

Lucas Van Valckenborch in Wiener Sammlungen

Diplomarbeit Titel der Diplomarbeit Lucas van Valckenborch in Wiener Sammlungen Verfasserin Ulrike Schmidl angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, im November 2010 Matrikel-Nummer: A 0503817 Studienkennzahl: A 315 Studienrichtung: Kunstgeschichte Betreuerin : Ao. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Monika Dachs-Nickel Inhalt I. Einleitung .......................................................................................................... 2 II. Provenienz ........................................................................................................ 4 III. Kostümentwürfe .............................................................................................. 10 1. Entwicklung der Kostümstudie ...................................................................................12 2. Einordnung der Kostümdarstellungen Valckenborchs ................................................13 3. Modische Gewänder in den Gemälden Valckenborchs ..............................................14 IV. Porträts ........................................................................................................... 17 1. Der Stand des Hofmalers im 16. Jahrhundert ............................................................17 2. Entwicklung des höfischen Bildnistypus .....................................................................21 3. Die Porträtliebe des Erzherzogs Matthias ..................................................................28 V. Monatsdarstellungen ..................................................................................... -

Gillis Mostaert Geschilderd in Opdracht Van De Moeten Zijn

1968/6 GILLIS MOST AERT plex was omstreeks het midden van de eeuw zo bouwvallig geworden, - doordat het aan de zuid 1530 1598) (Hulst ca. - Antwerpen zijde tot tegen de rui reikte, maakte waterschade een voortdurende versterking van de grondvesten noodzakelijk, - dat er een zegswijze bestond: beven gelijk het oud stadhuis. Reeds in 1541 be sloot de magistraat een gloednieuw raadhuis te bouwen. Op 27 februari 1561 had de eerste steen legging plaats en vier jaar later, in 1565, kon het imposante, in de 'moderne' renaissancestijl opge trokken gebouw plechtig in gebruik worden ge nomen. Indien we aanvaarden, dat het schilderij Christus door Pilatus aan het volk getoond tot stand kwam vóór de afbraak in 1565 van het oude raadhuis (theoretisch bestaat immers de mo Olieschildering op paneel - 120 x 151 cm gelijkheid dat het nadien werd geschilderd, terug grijpend op een vroegere afbeelding die ons niet Verzameling van het Stadhuls - Antwerpen bekend is), dan bekomen we als terminus ante quem het jaar der afbraak, 1565. In acht genomen echter het feit, dat men reeds in juni 1561 druk werkte aan de nieuwe bouw, waarvan in oktober 1562 het Het schilderij dat ons bezighoudt wordt in de oude houtwerk der eerste verdieping was opgetrokken, re literatuur beschreven als de voorstelling van een zou het schilderij, waarop van die bouwbedrijvig passiespel op de Grote Markt te Antwerpen, door heid geen spoor te merken valt, vóór 1561 ontstaan Gillis Mostaert geschilderd in opdracht van de moeten zijn. stedelijke magistraat, die uit piëteit een konter Ook op het stuk van de auteur worden we klaar en feitsel van het voor de slopershamer bestemde duidelijk door de gravure ingelicht: 'Mostart pin oude stadhuis wilde bewaren. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/206026 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-09-26 and may be subject to change. 18 De Zeventiende Eeuw 31 (2015) 1, pp. 18-54 - eISSN: 2212-7402 - Print ISSN: 0921-142x Coping with crisis Career strategies of Antwerp painters after 1585 David van der Linden David van der Linden is lecturer and nwo Veni postdoctoral fellow at the University of Groningen. He recently published Experiencing Exile. Huguenot Refugees in the Dutch Repu- blic, 1680-1700 (Ashgate, 2015). His current research project explores Protestant and Catholic memories about the French civil wars. [email protected] Abstract This article explores how painters responded to the crisis on the Antwerp art market in the 1580s. Although scholarship has stressed the profound crisis and subsequent emigration wave, prosopographical analysis shows that only a mino- rity of painters left the city. Demand for Counter-Reformation artworks allowed many to pursue their career in Antwerp, while others managed to survive the crisis by relying on cheap apprentices and the export of mass-produced paintings. Emigrant painters, on the other hand, minimised the risk of migration by settling in destinations that already had close artistic ties to Antwerp, such as Middelburg. Prosopographical analysis thus allows for a more nuanced understanding of artistic careers in the Low Countries. Keywords: Antwerp painters, career strategies, art market, guild of St.