British Honduras: the Invention of a Colonial Territory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Update Report

UPDATE REPORT DECEMBER, 2014 Mesoamerican Reef Fund www.marfund.org / [email protected] Picture by Ian Drysdale Dear Friends, We have finished one more productive year and we don’t want to let you go to your Holidays without knowing what progress we have had during the year. Please share among your network! Conservation of Marine Resources in Central America Project, Phase I The four protected areas that are part of Phase I of the Project have almost completed their third year of implementation. During this year, the most relevant advances in the areas, among many others were: the joint work that has begun between administrators, NGOs, stakeholders and coastal communities regarding management and of natural resources, community development and control and surveillance. Alternative productive activities have also started to generate income in some communities. Monitoring and environmental education programs have been consolidated. Because Phase I will end in December, 2016, in October, the areas began with the development of a Biennial Work Plan that will not only include field activities, but also closing activities in each protected area. With a biennial plan, the areas will be able to include sustainability plans towards continuity after the Project ends. The work plans are now being reviewed for approval. The mid-term evaluation of Phase I of the Project was held during the months of September, October and November. Key recommendations from this report are being taken into consideration in the biennial work plans, in order to improve and consolidate conservation actions in the areas. Technical and administrative follow up from our member funds and also our staff has been a key ingredient in the development of the field activities. -

The Song of Kriol: a Grammar of the Kriol Language of Belize

The Song of Kriol: A Grammar of the Kriol Language of Belize Ken Decker THE SONG OF KRIOL: A GRAMMAR OF THE KRIOL LANGUAGE OF BELIZE Ken Decker SIL International DIS DA FI WI LANGWIJ Belize Kriol Project This is a publication of the Belize Kriol Project, the language and literacy arm of the National Kriol Council No part of this publication may be altered, and no part may be reproduced in any form without the express permission of the author or of the Belize Kriol Project, with the exception of brief excerpts in articles or reviews or for educational purposes. Please send any comments to: Ken Decker SIL International 7500 West Camp Wisdom Rd. Dallas, TX 75236 e-mail: [email protected] or Belize Kriol Project P.O. Box 2120 Belize City, Belize c/o e-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] Copies of this and other publications of the Belize Kriol Project may be obtained through the publisher or the Bible Society Bookstore 33 Central American Blvd. Belize City, Belize e-mail: [email protected] © Belize Kriol Project 2005 ISBN # 978-976-95215-2-0 First Published 2005 2nd Edition 2009 Electronic Edition 2013 CONTENTS 1. LANGUAGE IN BELIZE ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 AN INTRODUCTION TO LANGUAGE ........................................................................................................ 1 1.2 DEFINING BELIZE KRIOL AND BELIZE CREOLE ...................................................................................... 2 1.3 -

Fronts in the World Ocean's Large Marine Ecosystems. ICES CM 2007

- 1 - This paper can be freely cited without prior reference to the authors International Council ICES CM 2007/D:21 for the Exploration Theme Session D: Comparative Marine Ecosystem of the Sea (ICES) Structure and Function: Descriptors and Characteristics Fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems Igor M. Belkin and Peter C. Cornillon Abstract. Oceanic fronts shape marine ecosystems; therefore front mapping and characterization is one of the most important aspects of physical oceanography. Here we report on the first effort to map and describe all major fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs). Apart from a geographical review, these fronts are classified according to their origin and physical mechanisms that maintain them. This first-ever zero-order pattern of the LME fronts is based on a unique global frontal data base assembled at the University of Rhode Island. Thermal fronts were automatically derived from 12 years (1985-1996) of twice-daily satellite 9-km resolution global AVHRR SST fields with the Cayula-Cornillon front detection algorithm. These frontal maps serve as guidance in using hydrographic data to explore subsurface thermohaline fronts, whose surface thermal signatures have been mapped from space. Our most recent study of chlorophyll fronts in the Northwest Atlantic from high-resolution 1-km data (Belkin and O’Reilly, 2007) revealed a close spatial association between chlorophyll fronts and SST fronts, suggesting causative links between these two types of fronts. Keywords: Fronts; Large Marine Ecosystems; World Ocean; sea surface temperature. Igor M. Belkin: Graduate School of Oceanography, University of Rhode Island, 215 South Ferry Road, Narragansett, Rhode Island 02882, USA [tel.: +1 401 874 6533, fax: +1 874 6728, email: [email protected]]. -

The Political Economy of Linguistic and Social Exchange Among The

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 Mayas, Markets, and Multilingualism: The Political Economy of Linguistic and Social Exchange in Cobá, Quintana Roo, Mexico Stephanie Joann Litka Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES MAYAS, MARKETS, AND MULTILINGUALISM: THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF LINGUISTIC AND SOCIAL EXCHANGE IN COBÁ, QUINTANA ROO, MEXICO By STEPHANIE JOANN LITKA A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Anthropology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Copyright 2012 Stephanie JoAnn Litka All Rights Reserved Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Stephanie JoAnn Litka defended this dissertation on October 28, 2011 . The members of the supervisory committee were: Michael Uzendoski Professor Directing Dissertation Robinson Herrera University Representative Joseph Hellweg Committee Member Mary Pohl Committee Member Gretchen Sunderman Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the [thesis/treatise/dissertation] has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For the people of Cobá, Mexico Who opened their homes, jobs, and hearts to me iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My fieldwork in Cobá was generously funded by the National Science Foundation, the Florida State University Center for Creative Research, and the Tinker Field Grant. I extend heartfelt gratitude to each organization for their support. In Mexico, I thank first and foremost the people of Cobá who welcomed me into their community over twelve years ago. I consider this town my second home and cherish the life-long friendships that have developed during this time. -

The Value of Turneffe Atoll Mangrove Forests, Seagrass Beds and Coral Reefs in Protecting Belize City from Storms

The Value of Turneffe Atoll Mangrove Forests, Seagrass Beds and Coral Reefs in Protecting Belize City from Storms Prepared by: Dr. Tony Fedler Gainesville, FL Prepared for: Turneffe Atoll Trust Belize City, Belize August 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. iii List of Tables……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. iv Ecosystem Services Provided by Coral Reefs, Mangrove Forests and Seagrass Beds………………………… 1 Measuring the Value of Shoreline Protection…………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Shoreline Protection Valuation Studies……………………………………………………………………………………………. 4 The Value of Shoreline Protection for Turneffe Atoll and Belize……………………………………………………….. 8 World Resources Institute Project……………………………………………………………………………………………… 8 Belize Coastal Zone Management Plan………………………………………………………………………………………. 10 Summary of Other Economic Benefits from Coral Reefs, Mangrove Forests and Seagrass Beds………. 14 Discussion and Conclusions……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 15 References………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 17 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project was initiated with funding from the Mesoamerican Reef Fund (MAR Fund) and Turneffe Atoll Trust. It was aided considerably by several congenial staff members of the Coastal Zone Management Authority & Institute (CZMAI). Ms. Andria Rosado, CZMAI GIS Technician, was very instrumental in providing valuable information for the Storm Mitigation Project. She generated ecosystems maps displaying three main ecosystems (i.e. seagrass, mangrove -

No. 10232 MULTILATERAL Agreement Establishing The

No. 10232 MULTILATERAL Agreement establishing the Caribbean Development Bank (with annexes, Protocol to provide for procedure for amendment of article 36 of the Agreement and Final Act of the Conference of Plenipotentiaries on the Caribbean Development Bank). Done at Kingston, Jamaica, on 18 October 1969 Authentic text: English. Registered ex officio on 26 January 1970. MULTILATÉRAL Accord portant création de la Banque de développement des Caraïbes (avec annexes, Protocole établissant la procé dure de modification de l'article 36 de l'Accord et Acte final de la Conférence de plénipotentiaires sur la Ban que de développement des Caraïbes). Fait à Kingston (Jamaïque), le 18 octobre 1969 Texte authentique: anglais. Enregistr d©office le 26 janvier 1970. 218 United Nations Treaty Series 1970 AGREEMENT 1 ESTABLISHING THE CARIBBEAN DEVEL OPMENT BANK The Contracting Parties, CONSCIOUS of the need to accelerate the economic development of States and Territories of the Caribbean and to improve the standards of living of their peoples; RECOGNIZING the resolve of these States and Territories to intensify economic co-operation and promote economic integration in the Caribbean; AWARE of the desire of other countries outside the region to contribute to the economic development of the region; CONSIDERING that such regional economic development urgently requires the mobilization of additional financial and other resources; and CONVINCED that the establishment of a regional financial institution with the broadest possible participation will facilitate -

Supreme Court Claim No. 376 of 2005

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF BELIZE, A.D. 2005 CLAIM NO. 376 SAID MUSA Claimant BETWEEN AND ANNMARIE WILLIAMS HARRY LAWRENCE REPORTER PRESS LIMITED Defendants __ BEFORE the Honourable Abdulai Conteh, Chief Justice. Mr. Kareem Musa for the claimant. Mr. Dean Barrow S.C. for the defendants. __ JUDGMENT Introduction Given the dramatis personae in this case which, by any account, contains an unusual cast, I had during the hearing constantly to remind myself that this was a trial of a claim in a court of law and not a political trial, whatever this may mean. On the one hand, is arrayed the Prime Minister and leader of one of the political parties (the PUP), who has his son as his attorney. Ranged on the other side is the Leader of the Opposition and the leader of the other main political party (the UDP) as the attorney for the defendants of whom the second defendant, Mr. H. 1 Lawrence admitted, albeit, under cross examination, that he was a founding member of the UDP. Mr. Lawrence who struck me as an honest witness now says his newspaper, The Reporter, supports no political party and has no partisan agenda. However, given the persons involved in this case, the political overtones of the case could not be missed. However, I need hardly say that this is a court of law and the issues joined between the parties are to be decided only in accordance with the law and evidence, and nothing more and nothing less. 2. Mr. Said Musa, the claimant in this case, is the Prime Minister of Belize, the Area Representative of the Fort George Division in the House of Representatives, leader of the People’s United Party (PUP), one of the two main political parties in the country, as well as a member of the bar with the rank of a Senior Counsel. -

Ongoing Struggles: Mayas and Immigrants in Tourist Era Tulum

Ongoing Struggles: Mayas and Immigrants in Tourist Era Tulum Tulum-an important Maya sea-trade center during the 13k, 14th, and 1 5 th centuries-now neighbors Mexico's most fashionable beach resort (Cancun) and has become the country's most popular archeological site. Since the 1970s, tourism, centerecL in the planned resort of Cancun, has over-shad- owed all other cultural and economic activities in the northern zone of Quintana Roo, Mexico. The tourism industry, including multinational capi- talist and national and international government agents, was designed to strengthen Mexico's abstract economy and alleviate its . ~~~~~~~unemployment and na- In Quintana Roo, Mexico, an area once con- uneloyent andena- trolled by Maya descendants of the mid-19d'-cen- tional debt payments tury Caste Wars of the Yucatan, the global tourist (Cardiel 1989; Garcia economyhas led to radical changes. This study ana- Villa 1992; Clancy lyzes relations between local'Mayas andYucatec and 1998). In the process, Mexican immigrants in Talum Pueblo, located tourism led to radical de- south of Cancun and just outside a popular archeo- mographic changes and logical site. Struggles between Mayas and immi- gave a special character grants have centered on cultural, marital and reli- to Quintana Roo's cul- gious practices and physical control of the town's ture and economy. Al- central church and plaza, eventually resulting in though a group ofMayas the establishment of dual, competing town centers. and mestizos known as Questions of cultural politics and the control o the Cruzoob once con- space continue to be central to contemporary po- troled the area, practic- litical movements around tde world. -

Table 1 Comprehensive International Points List

Table 1 Comprehensive International Points List FCC ITU-T Country Region Dialing FIPS Comments, including other 1 Code Plan Code names commonly used Abu Dhabi 5 971 TC include with United Arab Emirates Aden 5 967 YE include with Yemen Admiralty Islands 7 675 PP include with Papua New Guinea (Bismarck Arch'p'go.) Afars and Assas 1 253 DJ Report as 'Djibouti' Afghanistan 2 93 AF Ajman 5 971 TC include with United Arab Emirates Akrotiri Sovereign Base Area 9 44 AX include with United Kingdom Al Fujayrah 5 971 TC include with United Arab Emirates Aland 9 358 FI Report as 'Finland' Albania 4 355 AL Alderney 9 44 GK Guernsey (Channel Islands) Algeria 1 213 AG Almahrah 5 967 YE include with Yemen Andaman Islands 2 91 IN include with India Andorra 9 376 AN Anegada Islands 3 1 VI include with Virgin Islands, British Angola 1 244 AO Anguilla 3 1 AV Dependent territory of United Kingdom Antarctica 10 672 AY Includes Scott & Casey U.S. bases Antigua 3 1 AC Report as 'Antigua and Barbuda' Antigua and Barbuda 3 1 AC Antipodes Islands 7 64 NZ include with New Zealand Argentina 8 54 AR Armenia 4 374 AM Aruba 3 297 AA Part of the Netherlands realm Ascension Island 1 247 SH Ashmore and Cartier Islands 7 61 AT include with Australia Atafu Atoll 7 690 TL include with New Zealand (Tokelau) Auckland Islands 7 64 NZ include with New Zealand Australia 7 61 AS Australian External Territories 7 672 AS include with Australia Austria 9 43 AU Azerbaijan 4 994 AJ Azores 9 351 PO include with Portugal Bahamas, The 3 1 BF Bahrain 5 973 BA Balearic Islands 9 34 SP include -

302232 Travelguide

302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.1> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 INTRODUCTION 5 WELCOME 6 GENERAL VISITOR INFORMATION 8 GETTING TO BELIZE 9 TRAVELING WITHIN BELIZE 10 CALENDAR OF EVENTS 14 CRUISE PASSENGER ADVENTURES Half Day Cultural and Historical Tours Full Day Adventure Tours 16 SUGGESTED OVERNIGHT ADVENTURES Four-Day Itinerary Five-Day Itinerary Six-Day Itinerary Seven-Day Itinerary 25 ISLANDS, BEACHES AND REEF 32 MAYA CITIES AND MYSTIC CAVES 42 PEOPLE AND CULTURE 50 SPECIAL INTERESTS 57 NORTHERN BELIZE 65 NORTH ISLANDS 71 CENTRAL COAST 77 WESTERN BELIZE 87 SOUTHEAST COAST 93 SOUTHERN BELIZE 99 BELIZE REEF 104 HOTEL DIRECTORY 120 TOUR GUIDE DIRECTORY 302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.2> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.3> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 The variety of activities is matched by the variety of our people. You will meet Belizeans from many cultural traditions: Mestizo, Creole, Maya and Garifuna. You can sample their varied cuisines and enjoy their music and Belize is one of the few unspoiled places left on Earth, their company. and has something to appeal to everyone. It offers rainforests, ancient Maya cities, tropical islands and the Since we are a small country you will be able to travel longest barrier reef in the Western Hemisphere. from East to West in just two hours. Or from North to South in only a little over that time. Imagine... your Visit our rainforest to see exotic plants, animals and birds, possible destinations are so accessible that you will get climb to the top of temples where the Maya celebrated the most out of your valuable vacation time. -

The Geography of Fishing in British Honduras and Adjacent Coastal Areas

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1966 The Geography of Fishing in British Honduras and Adjacent Coastal Areas. Alan Knowlton Craig Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Craig, Alan Knowlton, "The Geography of Fishing in British Honduras and Adjacent Coastal Areas." (1966). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1117. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1117 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been „ . „ i i>i j ■ m 66—6437 microfilmed exactly as received CRAIG, Alan Knowlton, 1930— THE GEOGRAPHY OF FISHING IN BRITISH HONDURAS AND ADJACENT COASTAL AREAS. Louisiana State University, Ph.D., 1966 G eo g rap h y University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE GEOGRAPHY OP FISHING IN BRITISH HONDURAS AND ADJACENT COASTAL AREAS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State university and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by Alan Knowlton Craig B.S., Louisiana State university, 1958 January, 1966 PLEASE NOTE* Map pages and Plate pages are not original copy. They tend to "curl". Filmed in the best way possible. University Microfilms, Inc. AC KNQWLEDGMENTS The extent to which the objectives of this study have been acomplished is due in large part to the faithful work of Tiburcio Badillo, fisherman and carpenter of Cay Caulker Village, British Honduras. -

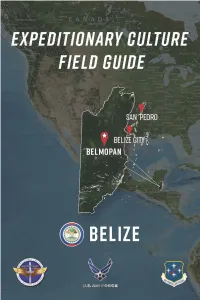

ECFG-Belize-2020R.Pdf

ECFG: Central America Central ECFG: About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo: US Marine shows members of Belize Defense Force how to load ammunition into weapons). The guide consists of 2 E parts: CFG Part 1 “Culture General” provides the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment with a focus on Central America (CENTAM). Part 2 “Culture Specific” describes unique cultural features of Belize Belizean society. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location. This section is designed to complement other pre- deployment training (Photo: USAF medic checks a Belizean patient’s vision during a medical readiness event). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact the AFCLC Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the express permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments.