Beyond the Bounds of Revolutions: Chinese in Transnational Anarchist Networks from the 1920S to the 1950S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Cross Bulletin

Black Cross Bulletin A Los Angeles Anarchist Black Cross Federation Publication SUMMER 2019 "The work isn’t done for the glory, but because we believe in Mutual Aid.” - Boris Yelensky Vol. 2 Issue 1 Janet, Janine and Eddie Freed After 40 Years On May 24, 2019, Janet Holloway Africa and Janine Phillips Africa of the MOVE 9 were released from state custody after more than forty years of incarceration. On June 21st, Eddie Africa was also released from prison. Imprisoned since 1978, these MOVE members have been battling for their freedom after being con - sistently denied parole for over a decade despite an impeccable disciplinary record and extensive record of mentorship and community service during their time in prison. They, along with the rest of the MOVE 9, were arrested after clash with the Philadelphia police department on August 8, 1978. The Move Organization owned a large twin house on the corner at 33rd and Pearl Street in the Powelton Village neigh - borhood of Philadelphia. Tensions began to increase between the city government and the MOVE organization due to a combina - destroying most of the evidence. On May 4, However, the rest of the MOVE members tion of neighborhood complaints and con - 1980, a judge pronounced the nine mem - were denied parole in 2018. After the frontations with government agencies. The bers of MOVE (the MOVE 9) guilty and denials, attorneys from Abolitionist Law MOVE organization, believing they were sentenced them to 30-100 years for the Center and People’s Law Office filed peti - going to be attacked by the police, began to third-degree murder of the police officer. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/04/2021 08:07:20AM This Is an Open Access Chapter Distributed Under the Terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR HISTORY, CULTURE AND MODERNITY www.history-culture-modernity.org Published by: Uopen Journals Copyright: © The Author(s). Content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence eISSN: 2213-0624 L’Art pour l’Art or L’Art pour Tous? The Tension Between Artistic Autonomy and Social Engagement in Les Temps Nouveaux, 1896–1903 Laura Prins HCM 4 (1): 92–126 DOI: 10.18352/hcm.505 Abstract Between 1896 and 1903, Jean Grave, editor of the anarchist journal Les Temps Nouveaux, published an artistic album of original prints, with the collaboration of (avant-garde) artists and illustrators. While anar- chist theorists, including Grave, summoned artists to create social art, which had to be didactic and accessible to the working classes, artists wished to emphasize their autonomous position instead. Even though Grave requested ‘absolutely artistic’ prints in the case of this album, artists had difficulties with creating something for him, trying to com- bine their social engagement with their artistic autonomy. The artistic album appears to have become a compromise of the debate between the anarchist theorists and artists with anarchist sympathies. Keywords: anarchism, France, Neo-Impressionism, nineteenth century, original print Introduction While the Neo-Impressionist painter Paul Signac (1863–1935) was preparing for a lecture in 1902, he wrote, ‘Justice in sociology, har- mony in art: same thing’.1 Although Signac never officially published the lecture, his words have frequently been cited by scholars since the 1960s, who claim that they illustrate the widespread modern idea that any revolutionary avant-garde artist automatically was revolutionary in 92 HCM 2016, VOL. -

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926 Hongkong Workers in an Anti-Imperialist Movement Robert JamesHorrocks Submitted in accordancewith the requirementsfor the degreeof PhD The University of Leeds Departmentof East Asian Studies October 1994 The candidateconfirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where referencehas been made to the work of others. 11 Abstract In this thesis, I study the Guangzhou-Hongkong strike of 1925-1926. My analysis differs from past studies' suggestions that the strike was a libertarian eruption of mass protest against British imperialism and the Hongkong Government, which, according to these studies, exploited and oppressed Chinese in Guangdong and Hongkong. I argue that a political party, the CCP, led, organised, and nurtured the strike. It centralised political power in its hands and tried to impose its revolutionary visions on those under its control. First, I describe how foreign trade enriched many people outside the state. I go on to describe how Chinese-run institutions governed Hongkong's increasingly settled non-elite Chinese population. I reject ideas that Hongkong's mixed-class unions exploited workers and suggest that revolutionaries failed to transform Hongkong society either before or during the strike. My thesis shows that the strike bureaucracy was an authoritarian power structure; the strike's unprecedented political demands reflected the CCP's revolutionary political platform, which was sometimes incompatible with the interests of Hongkong's unions. I suggestthat the revolutionary elite's goals were not identical to those of the unions it claimed to represent: Hongkong unions preserved their autonomy in the face of revolutionaries' attempts to control Hongkong workers. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 159 2nd International Conference on Judicial, Administrative and Humanitarian Problems of State Structures and Economical Subjects (JAHP 2017) Modern Chinese Students Studying in Japan and Xiangshan Society Peng Jiao College of Humanities Jinan University Zhuhai, China Abstract—The defeat of the Sino-Japanese war in 1894 country. China signed Treaty of Shimonoseki. We ceded greatly changed the Chinese people's ideas and thoughts. territory and paid indemnities to Japan. It greatly shocked Chinese people realize that Japan has developed because of Chinese and aroused our reflection. This kind of reflection is sending students abroad. Domestic media called on the based on the re-examination of Japan, which greatly changed government to send students abroad. In 1902, the Qing our people's ideas and thoughts. Chinese have come to realize government implemented a new policy requiring all localities to that the development of Japan in just a few decades was due send students to Japan. The number of students going to Japan to sending students to study abroad. Therefore, domestic had soared. In this trend, a large number of Xiangshan media called on the government to send students to study in students followed it and also went to Japan. After the students Japan. Governors including Zhang Zhidong advocated returned to their hometown, they ran a newspaper and sending students to study abroad. He vigorously advocated organized societies for revolutionary propaganda, and also managed education business in hometown to expand Esperanto; sending students to study abroad in his Encourage to Study these activities have affected the changes of modern Xiangshan Abroad published in April 1898. -

De AS 104/105

anarchistisch tijdschrift Een en twintigste jaargang, nr. 104, najaar 1993 / Twee en twintigste jaargang, nr. 105, winter 1994. De AS verschijnt vier maal per jaar en is een uitgave van Stichting De AS, Moerkapelle. ISSN-nummer 0920-3257. Bestelling: door storting op postgiro 4460315 van de AS te Moerkapelle. Jaarabonnement: ƒ28,-; buiten Benelux f34,- Druk: Macula, Boskoop. Zetwerk: Stichting Rode Emma, Amsterdam. Adreswijzigingen: bij voorkeur per briefkaart, of per giro (verbeter het adres op de kaart) graag met vermelding van de postcode. Reklamering: met vermelding van de laatste betaaldatum, als aangegeven in uw giro- administratie. Nieuwe abonnementen: gaan in met het eerste nummer van de jaargang, tenzij anders aangegeven bij bestelling. Zonder opzegging worden abonnementen verlengd. Redactie-adres: postbus 35061, 3005 DB Rotterdam. Administratie-adres: postbus 43,2750 AA Moerkapelle. Redactie: Cees Bronsveld, Marius de Geus, Thom Holterman, Rudolf de Jong, Jaap van der Laan, Wim de Lobel, Bas Moreel, Simon Radius, Hans Ramaer. Omslagontwerp: Detlef Greinert. Verder werkten mee: Machteld Bakker, Aat Brand, Francis Faes, Eric Goeman, Marli Huijer, Roger Jacobs, Jan Moulaert, André de Raaij, Hein Westerouen van Meeteren, Dick de Winter. EEN WITLOFMONARCHIE IN DE GREEP VAN HET POPULISME Eric Goeman "La Belgique qu'elle créve" riep Vlaams Blok volksvertegenwoordiger Joris Van Hauthem tijdens het debat over de staatshervorming in het parlement. "Leve de republiek. Vive Julien Lahaut" riep ex-beursgoeroe, Ferrarimaniak en volksvertegenwoordiger Jean-Pierre van Rossem tijdens de kroningsplechtigheid van Albert II in het parlement. (Julien Lahaut was een communistisch voorman en volksvertegenwoordiger die tijdens de eedaflegging in 1951 van Boudewijn I "Vive la république" riep. -

ABOR and the ~EW Peal: the CASE - - of the ~OS ~NGELES J~~~Y

~ABOR AND THE ~EW pEAL: THE CASE - - OF THE ~OS ~NGELES J~~~y By ISAIAS JAMES MCCAFFERY '\ Bachelor of Arts Missouri Southern State College Joplin, Missouri 1987 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of Oklahoma Siate University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS December, 1989 { Oklahoma ~tate univ •.1...u..1u.Lu..1.; LABOR AND THE NEW DEAL: THE CASE OF THE LOS ANGELES ILGWC Thesis Approved: Dean of the Graduate College 1.i PREFACE This project examines the experience of a single labor union, the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union (ILGWU), in Los Angeles during the New Deal era. Comparisons are drawn between local and national developments within the ILGWU and the American labor movement in general. Surprisingly little effort has been made to test prevailing historical interpretations within specific cities-- especially those lying outside of the industrial northeast. Until more localized research is undertaken, the unique organizational struggles of thousands of working men and women will remain ill-understood. Differences in regional politics, economics, ethnicity, and leadership defy the application of broad-based generalizations. The Los Angeles ILGWU offers an excellent example of a group that did not conform to national trends. While the labor movement experienced remarkable success throughout much of the United States, the Los Angeles garment locals failed to achieve their basic goals. Although eastern clothing workers won every important dispute with owners and bargained from a position of strength, their disunited southern Californian counterparts languished under the counterattacks of business interests. No significant gains in ILGWU membership occurred in Los Angeles after 1933, and the open shop survived well iii into the following decade. -

Esperanto and Chinese Anarchism in the 1920S and 1930S

The Anarchist Library (Mirror) Anti-Copyright Esperanto and Chinese anarchism in the 1920s and 1930s Gotelind Müller and Gregor Benton Gotelind Müller and Gregor Benton Esperanto and Chinese anarchism in the 1920s and 1930s 2006 Retrieved on 22nd April 2021 from archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de usa.anarchistlibraries.net 2006 Zhou Enlai Zhou Zuoren Ziyou shudian Contents Introduction ..................... 5 Xuehui and Erošenko ................ 7 Anarchism and Esperanto in the late 1920s . 16 Anarchism and Esperanto in China in the 1930s 17 Conclusions ...................... 21 Bibliography ..................... 23 Glossary ........................ 25 30 3 “Wang xiangcun qu” wanguo xinyu “Wanguo xinyu”“Wo de shehui geming de yi- jian” Wu Jingheng (= Wu Zhihui) Wu Zhihui Wuxu Wuzhengfu gongchan zhuyi she “Xiandai xiju yishu zai Zhongguo de jianzhi” Xianmin Xin qingnian Xin she Xin shiji “Xinyu wenti zhi zada” Xing Xiwangzhe Xuantian Xuehui Xu Anzhen “Xu ‘Haogu zhi chengjian’” Xu Lunbo “Xu Lunbo xiansheng” “Xu ‘Pi miu’” Xu Shanguang / Liu Jianping / Xu Shanshu “Xu wanguo xinyu zhi jinbu” “Xu xinyu wenti zhi zada” Yamaga Taiji Ye Laishi Yuan Shikai “Zenyang xuanchuan zhuyi” Zhang Binglin Zhang Jiang (= Zhang Binglin) Zhang Jingjiang Zhang Qicheng Zheng Bi’an Zheng Chaolin Zheng Peigang Zheng Taipu “Zhishi jieji de shiming” “Zhongguo gudai wuzhengfuzhuyi chao zhi yipie” Zhongguo puluo shijieyuzhe lianmeng Zhongguo wuzhengfuzhuyi he Zhongguo shehuidang 29 Min Esperanto in China and among the Chinese diaspora was for Minbao long periods closely linked with anarchism. This article looks Ming Minguo ribao at the history of the Chinese Esperanto movement after the Minsheng repatriation of anarchism to China in the 1910s. It examines Minshengshe jishilu Esperanto’s political connections in the Chinese setting and Miyamoto Masao the arguments used by its supporters to promote the language. -

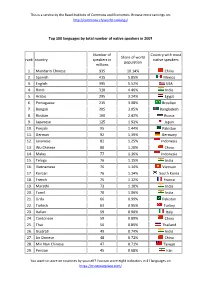

Top 100 Languages by Total Number of Native Speakers in 2007 Rank

This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. Browse more rankings on: http://commons.ch/world-rankings/ Top 100 languages by total number of native speakers in 2007 Number of Country with most Share of world rank country speakers in native speakers population millions 1. Mandarin Chinese 935 10.14% China 2. Spanish 415 5.85% Mexico 3. English 395 5.52% USA 4. Hindi 310 4.46% India 5. Arabic 295 3.24% Egypt 6. Portuguese 215 3.08% Brasilien 7. Bengali 205 3.05% Bangladesh 8. Russian 160 2.42% Russia 9. Japanese 125 1.92% Japan 10. Punjabi 95 1.44% Pakistan 11. German 92 1.39% Germany 12. Javanese 82 1.25% Indonesia 13. Wu Chinese 80 1.20% China 14. Malay 77 1.16% Indonesia 15. Telugu 76 1.15% India 16. Vietnamese 76 1.14% Vietnam 17. Korean 76 1.14% South Korea 18. French 75 1.12% France 19. Marathi 73 1.10% India 20. Tamil 70 1.06% India 21. Urdu 66 0.99% Pakistan 22. Turkish 63 0.95% Turkey 23. Italian 59 0.90% Italy 24. Cantonese 59 0.89% China 25. Thai 56 0.85% Thailand 26. Gujarati 49 0.74% India 27. Jin Chinese 48 0.72% China 28. Min Nan Chinese 47 0.71% Taiwan 29. Persian 45 0.68% Iran You want to score on countries by yourself? You can score eight indicators in 41 languages on https://trustyourplace.com/ This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. -

Anarchism in the Chinese Revolution Was Also a Radical Educational Institution Modeled After Socialist 1991 36 for This Information, See Ibid., 58

only by rephrasing earlier problems in a new discourse that is unmistakably modern in its premises and sensibilities; even where the answers are old, the questions that produced them have been phrased in the problematic of a new historical situation. The problem was especially acute for the first generation of intellec- Anarchism in the Chinese tuals to become conscious of this new historical situation, who, Revolution as products of a received ethos, had to remake themselves in the very process of reconstituting the problematic of Chinese thought. Anarchism, as we shall see, was a product of this situation. The answers it offered to this new problematic were not just social Arif Dirlik and political but sought to confront in novel ways its demands in their existential totality. At the same time, especially in the case of the first generation of anarchists, these answers were couched in a moral language that rephrased received ethical concepts in a new discourse of modernity. Although this new intellectual problematique is not to be reduced to the problem of national consciousness, that problem was important in its formulation, in two ways. First, essential to the new problematic is the question of China’s place in the world and its relationship to the past, which found expression most concretely in problems created by the new national consciousness. Second, national consciousness raised questions about social relationships, ultimately at the level of the relationship between the individual and society, which were to provide the framework for, and in some ways also contained, the redefinition of even existential questions. -

Women and the Law Reprinted Congressional

WOMEN AND THE LAW REPRINTED FROM THE 2007 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2007 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 40–784 PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 13:14 Feb 20, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\40784.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate SANDER LEVIN, Michigan, Chairman BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota, Co-Chairman MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio MAX BAUCUS, Montana MICHAEL M. HONDA, California CARL LEVIN, Michigan TOM UDALL, New Mexico DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TIMOTHY J. WALZ, Minnesota SHERROD BROWN, Ohio DONALD A. MANZULLO, Illinois SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas JOSEPH R. PITTS, Pennsylvania CHUCK HAGEL, Nebraska EDWARD R. ROYCE, California GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey MEL MARTINEZ, Florida EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS PAULA DOBRIANSKY, Department of State CHRISTOPHER R. HILL, Department of State HOWARD M. RADZELY, Department of Labor DOUGLAS GROB, Staff Director MURRAY SCOT TANNER, Deputy Staff Director (II) VerDate 0ct 09 2002 13:14 Feb 20, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 U:\DOCS\40784.TXT DEIDRE C O N T E N T S Page Status of Women ............................................................................................. -

Anarchist Cybernetics Control and Communication in Radical Left Social Movements

ANARCHIST CYBERNETICS CONTROL AND COMMUNICATION IN RADICAL LEFT SOCIAL MOVEMENTS Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester by Thomas Swann MA (University of Glasgow), MA (Radboud University Nijmegen) School of Management University of Leicester September 2015 Thesis Abstract Anarchist Cybernetics Control and Communication in Radical Left Social Movements by Thomas Swann This thesis develops the concept of anarchist cybernetics in an attempt to elaborate an understanding of the participatory and democratic forms of organisation that have characterised radical left-wing social movements in recent years. Bringing together Stafford Beer’s organisational cybernetics and the organisational approaches of both classical and contemporary anarchism, an argument is made for the value of an anarchist cybernetic perspective that goes beyond the managerialism cybernetics has long been associated with. Drawing on theoretical reflection and an empirical strategy of participatory political philosophy, the thesis examines contemporary social movement organisational practices through two lenses: control and communication. Articulating control as self-organisation, in line with cybernetic thought, an argument is made for finding a balance between, on the one hand, strategic identity and cohesion and, on the other, tactical autonomy. While anarchist and radical left activism often privileges individual autonomy, it is suggested here that too much autonomy or tactical flexibility can be as damaging to a social movement organisation as over-centralisation. Turning to communication, the thesis looks at social media, the focus of another kind of hype in recent activism, and identifies both the potentials and the problems of using social media platforms in anarchist and radical left organisation. -

The Rise of Ethical Anarchism in Britain, 1885-1900

1 e[/]pater 2 sie[\]cle THE RISE OF ETHICAL ANARCHISM IN BRITAIN 1885-1900 By Mark Bevir Department of Politics Newcastle University Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 7RU U.K. ABSTRACT In the nineteenth century, anarchists were strict individualists favouring clandestine organisation and violent revolution: in the twentieth century, they have been romantic communalists favouring moral experiments and sexual liberation. This essay examines the growth of this ethical anarchism in Britain in the late nineteenth century, as exemplified by the Freedom Group and the Tolstoyans. These anarchists adopted the moral and even religious concerns of groups such as the Fellowship of the New Life. Their anarchist theory resembled the beliefs of counter-cultural groups such as the aesthetes more closely than it did earlier forms of anarchism. And this theory led them into the movements for sex reform and communal living. 1 THE RISE OF ETHICAL ANARCHISM IN BRITAIN 1885-1900 Art for art's sake had come to its logical conclusion in decadence . More recent devotees have adopted the expressive phase: art for life's sake. It is probable that the decadents meant much the same thing, but they saw life as intensive and individual, whereas the later view is universal in scope. It roams extensively over humanity, realising the collective soul. [Holbrook Jackson, The Eighteen Nineties (London: G. Richards, 1913), p. 196] To the Victorians, anarchism was an individualist doctrine found in clandestine organisations of violent revolutionaries. By the outbreak of the First World War, another very different type of anarchism was becoming equally well recognised. The new anarchists still opposed the very idea of the state, but they were communalists not individualists, and they sought to realise their ideal peacefully through personal example and moral education, not violently through acts of terror and a general uprising.