B Forecasts of Aviation Activity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sacramento International Airport Airline Passenger Statistics July 2011

Sacramento International Airport Airline Passenger Statistics July 2011 CURRENT MONTH FISCAL YEAR TO DATE CALENDAR YEAR TO DATE THIS YEAR LAST YEAR % + / ( - ) 2011/12 2010/11 % + / ( - ) 2011 2010 % + / ( - ) Enplaned Domestic Alaska Airlines 25,451 25,519 (0.3%) 25,451 25,519 (0.3%) 137,442 123,342 11.4% American Airlines 21,359 16,593 28.7% 21,359 16,593 28.7% 125,549 107,297 17.0% Continental Airlines 13,524 14,658 (7.7%) 13,524 14,658 (7.7%) 91,916 94,379 (2.6%) Delta Airlines 34,719 36,317 (4.4%) 34,719 36,317 (4.4%) 165,845 184,669 (10.2%) Frontier Airlines 14,565 15,931 (8.6%) 14,565 15,931 (8.6%) 75,597 84,949 (11.0%) Hawaiian Airlines 7,573 7,536 0.5% 7,573 7,536 0.5% 50,427 49,307 2.3% Horizon Air 11,316 13,753 (17.7%) 11,316 13,753 (17.7%) 69,346 81,296 (14.7%) Jet Blue 11,909 10,453 13.9% 11,909 10,453 13.9% 67,313 64,002 5.2% Mesa/US Airways Express/YV - 753 (100.0%) - 753 (100.0%) 3,472 2,821 23.1% Skywest/Delta Connection 11,149 5,818 91.6% 11,149 5,818 91.6% 57,907 31,982 81.1% Skywest/United Express 13,461 15,635 (13.9%) 13,461 15,635 (13.9%) 97,706 107,786 (9.4%) Southwest 192,922 205,786 (6.3%) 192,922 205,786 (6.3%) 1,328,959 1,380,693 (3.7%) United Airlines 28,903 29,249 (1.2%) 28,903 29,249 (1.2%) 171,877 173,518 (0.9%) US Airways 25,959 25,755 0.8% 25,959 25,755 0.8% 129,707 129,309 0.3% CHARTER - - - - - - 412,810 423,756 (2.6%) 412,810 423,756 (2.6%) 2,573,063 2,615,350 (1.6%) International AeroMexico 1,583 - 1,583 - 1,583 - Alaska Airlines 1,665 - 1,665 - 12,220 - Mexicana - 5,303 (100.0%) - 5,303 (100.0%) - -

Forecasts of Aviation Activity

CHAPTER B Forecasts of Aviation Activity: Forecasting is a key element in any airport master planning process. The forecast process is essential for analyzing existing airport facilities and identifying further needs and requirements of the facilities that may arise over the next 20 years. The relationship between aviation activity and projected demand is an indicator as to the type, timing, and allocation of future airport infrastructure, equipment, and service needs. For the purposes of this Airport Master Plan, the most important element of the forecasts chapter is the documentation of existing aircraft operations by type and size of aircraft as well as the future projections of operations by type and size of aircraft. One of the assumed outcomes of this planning process was that the type and size of aircraft using the Airport on a regular basis are larger than what RNT was originally designed for. The trend of more operations by larger design aircraft is forecast to continue and warrants a design standard change for RNT. This change in design standards is further discussed starting on Page B.37 with the conclusion being that the Airport is, in fact, in need of a design standards upgrade in accordance with FAA guidance. Introduction. The RNT aviation activity forecasts in this chapter are developed for a 20-year planning period and are based on historic activity, industry trends, local socioeconomic data, and changes at RNT since the completion of previous planning studies. The forecasts utilize FY2015 (October 2014 through September 2015) as the base year and project future activity through 2035, identified in 5-year increments. -

(Asos) Implementation Plan

AUTOMATED SURFACE OBSERVING SYSTEM (ASOS) IMPLEMENTATION PLAN VAISALA CEILOMETER - CL31 November 14, 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Weather Service / Office of Operational Systems/Observing Systems Branch National Weather Service / Office of Science and Technology/Development Branch Table of Contents Section Page Executive Summary............................................................................ iii 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................... 1 1.1 Background.......................................................................... 1 1.2 Purpose................................................................................. 2 1.3 Scope.................................................................................... 2 1.4 Applicable Documents......................................................... 2 1.5 Points of Contact.................................................................. 4 2.0 Pre-Operational Implementation Activities ............................ 6 3.0 Operational Implementation Planning Activities ................... 6 3.1 Planning/Decision Activities ............................................... 7 3.2 Logistic Support Activities .................................................. 11 3.3 Configuration Management (CM) Activities....................... 12 3.4 Operational Support Activities ............................................ 12 4.0 Operational Implementation (OI) Activities ......................... -

Integrated Report 2020 Index

INTEGRATED REPORT 2020 INDEX 4 28 70 92 320 PRESENTATION CORPORATE GOVERNANCE SECURITY METHODOLOGY SWORN STATEMENT 29 Policies and practices 71 Everyone’s commitment 93 Construction of the report 31 Governance structure 96 GRI content index 35 Ownership structure 102 Global Compact 5 38 Policies 103 External assurance 321 HIGHLIGHTS 74 104 Glossary CORPORATE STRUCTURE LATAM GROUP EMPLOYEES 42 75 Joint challenge OUR BUSINESS 78 Who makes up LATAM group 105 12 81 Team safety APPENDICES 322 LETTER FROM THE CEO 43 Industry context CREDITS 44 Financial results 47 Stock information 48 Risk management 83 50 Investment plan LATAM GROUP CUSTOMERS 179 14 FINANCIAL INFORMATION INT020 PROFILE 84 Connecting people This is a 86 More digital travel experience 180 Financial statements 2020 navigable PDF. 15 Who we are 51 270 Affiliates and subsidiaries Click on the 17 Value generation model SUSTAINABILITY 312 Rationale buttons. 18 Timeline 21 Fleet 52 Strategy and commitments 88 23 Passenger operation 57 Solidary Plane program LATAM GROUP SUPPLIERS 25 LATAM Cargo 62 Climate change 89 Partner network 27 Awards and recognition 67 Environmental management and eco-efficiency Presentation Highlights Letter from the CEO Profile Corporate governance Our business Sustainability Integrated Report 2020 3 Security Employees Customers Suppliers Methodology Appendices Financial information Credits translated at the exchange rate of each transaction date, • Unless the context otherwise requires, references to “TAM” although a monthly rate may also be used if exchange rates are to TAM S.A., and its consolidated affiliates, including do not vary widely. TAM Linhas Aereas S.A. (“TLA”), which operates under the name “LATAM Airlines Brazil”, Fidelidade Viagens e Turismo Conventions adopted Limited (“TAM Viagens”), and Transportes Aéreos Del * Unless the context otherwise requires, references to Mercosur S.A. -

13 November 2019 (Revised) Mr. Alex Wilcox, CEO JSX

The Leader in Scientific Consulting and Research… SAN DIEGO CORPORATE OFFICE P.O. Box 488, Ramona, CA 92065 Phone: 760-787-0016 www.ise.us 13 November 2019 (Revised) Mr. Alex Wilcox, CEO JSX 1341 W. Mockingbird Ln. Suite 600E Dallas, TX 75247 RE: ACOUSTICAL COMPLIANCE MONITORING & VALIDATION TESTING JSX AIRLINES OVERFLIGHT ACTIVITIES – NEWPORT BEACH, CA ISE PROJECT #19-012 Dear Alex: At your request, Investigative Science and Engineering, Inc. (ISE) has been retained to perform acoustical compliance monitoring and validation testing of existing overflight activities from John Wayne Airport (JWA), and their effects on the coastal Newport Beach / Balboa Island area. Our findings are presented in this summary letter report. Background and Need John Wayne Airport (FAA Airport Code SNA) is owned and operated by the County of Orange, and is the only commercial service airport in the county that provides commercial passenger and air-cargo service as well as being the primary provider of general aviation services. JWA’s location with respect to the subject study/testing area, and respective coastal overflight path (red dashed arrow), are shown in Figures 1 and 2 starting on the following page. Ongoing public concerns regarding general aircraft overflight noise from JWA has prompted JSX to explore modified flight operations to determine their efficacy in reducing overall noise exposure to the Newport Beach coastal area. Currently departing aircraft from JWA assume an approximate steady (linear) climb rate towards the coast, the so-called NextGen route, as shown in Figures 1 and 2. JSX is proposing a ‘modified’ flight path, which follows the same horizontal alignment as the NextGen path, but modifies the climb-rate to achieve a higher altitude earlier along the flight path, with the hope that this produces a smaller overall acoustical signature. -

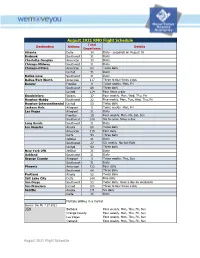

JSX August 2021 RNO Flight Schedule

August 2021 RNO Flight Schedule Total Destination Airlines Details Departures Atlanta Delta 14 Daily - suspends on August 16 Burbank Southwest 31 Daily Charlotte-Douglas American 30 Daily Chicago-Midway Southwest 31 Daily Chicago-O'Hare American 60 Twice daily United 31 Daily Dallas-Love Southwest 31 Daily Dallas/Fort Worth American 117 Three to four times a day Denver Frontier 9 Twice weekly. Mon, Fri Southwest 89 Three daily United 124 Four times a day Guadalajara Volaris 17 Four weekly. Mon, Wed, Thu, Fri Houston-Hobby Southwest 22 Five weekly. Mon, Tue, Wed, Thu, Fri Houston-Intercontinental United 53 Twice daily Jackson Hole Allegiant 5 Twice weekly. Mon, Fri Las Vegas Allegiant 31 Daily Frontier 19 Four weekly. Mon, Fri, Sat, Sun Southwest 204 Six to seven times a day Long Beach Southwest 31 Daily Los Angeles Alaska 60 Twice daily American 119 Four daily Delta 93 Three daily JetBlue 31 Daily Southwest 27 Six weekly. No Sat flight United 93 Three daily New York-JFK JetBlue 31 Daily Oakland Southwest 31 Daily Orange County Allegiant 9 Twice weekly. Thu, Sun Southwest 31 Daily Phoenix American 122 Four daily Southwest 84 Three daily Portland Alaska 52 Twice daily Salt Lake City Delta 144 Five daily San Diego Southwest 53 Twice daily. Once a day on weekends San Francisco United 105 Three to four times a day Seattle Alaska 171 Six daily Delta 35 Daily Multiple airlines in a market Source: Diio Mi, 7.27.2021 JSX Burbank Four weekly. Mon, Thu, Fri, Sun Orange County Four weekly. Mon, Thu, Fri, Sun Las Vegas Four weekly. -

JSX RNO Route Relaunch Fall 2020.Pdf

JSX LAUNCHES HOP-ON FLIGHTS TO RENO–TAHOE FROM BURBANK In Tandem With Reno-Tahoe Airport Authority and Regional Air Service Corporation, The Pioneering Hop- On Jet Service Introduces Hassle-Free Flights Between Southern California and "The Biggest Little City in the World" (DALLAS, Texas) – September 4, 2020 – This Fall, JSX––the revolutionary hop-on jet service dedicated to making short-haul air travel simple and joyful––launches service to "The Biggest Little City in the World" with roundtrip flights to and from Burbank. Air travelers can book online starting today at www.jsx.com for flights beginning on Thursday, September 24, 2020. Tickets start at $89 each way to/from Burbank. In collaboration with the Reno-Tahoe Airport Authority (RTAA) and Regional Air Service Corporation (RASC), JSX is introducing service with four new round-trip flights per week between Reno and Burbank on Monday, Thursday, Friday, and Sunday. The flights will operate between private terminals at Reno-Tahoe International Airport (RNO) and Hollywood Burbank International Airport (BUR). In partnership with the prominent tourism entities promoting air travel to Reno, JSX will provide a safe, worry-free flight experience for those seeking weekend getaways or essential business trips to the stunning Sierra Nevada mountain region. “We are excited to partner with RTAA and RASC to offer new service between Burbank and Reno, and provide the region with our innovative, simple and safe point-to-point service,” states JSX CEO, Alex Wilcox. “I’m very pleased with this collaboration and want to thank both the Airport Authority and the Regional Air Service Corporation for making this a reality. -

Pierce County Public Works and Utilities Brian J

Pierce County Public Works and Utilities Brian J. Ziegler, P.E. 2702 South 42nd Street, Suite 201 Director Tacoma, Washington 98409-7322 [email protected] piercecountywa.org/pwu TO: Dan Roach, Chair Pierce County Council FROM: Deb Wallace, Airport and Ferry Administrator DATE: October 28, 2014 SUBJECT: Airport Security The purpose of this briefing paper is to provide an update to Council on the status of security upgrades at Pierce County's airports. Current Situation: The Pierce County Airport and Ferry division is in the process of upgrading gate access, fencing, and security lighting at both airports. In 2015 the division will implement an Airport Watch program to increase the safety and security at each facility. The improvements are being made due to incidents which have occurred at the airports over the last several years and at the request of airport tenants. Currently both airports are fenced with restricted access gates to enhance security, although there are gaps in the fencing allowing unauthorized pedestrian entry. These gaps will be addressed in early 2015. An electronic gate is being added to the north gate at Tacoma Narrows Airport (TIW) and the south gate is being outfitted with a mechanism to allow its use by those who are hearing impaired. Once that improvement is completed, 24 hour security will be implemented at TIW. Thun Field currently operates with 24 hour gate security. Prior to implementation, the airport commissions at each airport discussed airport security measures during the preceding year and staff coordinated the implementation of the security measures with airport tenants. -

Confidential Position Specification Reno-Tahoe Airport Authority

CONFIDENTIAL DRAFT Confidential Position Specification Reno-Tahoe Airport Authority President & Chief Executive Officer March 2020 CONFIDENTIAL POSITION SPECIFICATION Position President & Chief Executive Officer Company Reno-Tahoe Airport Authority Location Reno, Nevada Reporting Relationship Reports to the Board of Trustees Website https://www.renoairport.com COMPANY BACKGROUND The Reno-Tahoe Airport Authority (“the Authority”, “RTAA”, or “the airport”) is the owner and operator of Reno-Tahoe International Airport (RNO) and Reno-Stead Airport (RTS), a general aviation facility. The RTAA is an independent entity that is not part of any other unit of local government and does not use local property or sales tax revenue to fund its operation. The Authority is governed by a nine-member Board of Trustees, operates as a business, and receives no local tax dollars. The Reno-Tahoe International Airport is a very important asset to the region, with the 4.4 million passengers going through the airport in 2019 (66th busiest in the United States), bringing $3.2 billion in economic impact to the region. The Authority employs approximately 280 direct airport staff and over 2,400 other staff work on airport premises for various tenants and other companies. RNO is located just five minutes from downtown Reno, therefore, it is literally and figuratively at the heart of the community and only 40 minutes from some of the finest ski resorts and outdoor recreation in the world. The airport makes the all-important first and last impression on passengers coming and going from the region. The Airport truly plays a vital role for the hotel casinos, ski resorts, golf courses, the University of Nevada, and a growing restaurant scene and high-tech business district. -

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE on AIR LAW (Montréal, 20 April to 2

DCCD Doc No. 28 28/4/09 (English only) INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON AIR LAW (Montréal, 20 April to 2 May 2009) CONVENTION ON COMPENSATION FOR DAMAGE CAUSED BY AIRCRAFT TO THIRD PARTIES AND CONVENTION ON COMPENSATION FOR DAMAGE TO THIRD PARTIES, RESULTING FROM ACTS OF UNLAWFUL INTERFERENCE INVOLVING AIRCRAFT (Presented by the Air Crash Victims Families Group) 1. INTRODUCTION – SUPPLEMENTAL AND OTHER COMPENSATIONS 1.1 The apocalyptic terrorist attack by the means of four hi-jacked planes committed against the World Trade Center in New York, NY , the Pentagon in Arlington, VA and the aborted flight ending in a crash in the rural area in Shankville, PA ON September 11th, 2001 is the only real time example that triggered this proposed Convention on Compensation for Damage to Third Parties from Acts of Unlawful Interference Involving Aircraft. 1.2 It is therefore important to look towards the post incident resolution of this tragedy in order to adequately and pro actively complete ONE new General Risk Convention (including compensation for ALL catastrophic damages) for the twenty first century. 2. DISCUSSION 2.1 Immediately after September 11th, 2001 – the Government and Congress met with all affected and interested parties resulting in the “Air Transportation Safety and System Stabilization Act” (Public Law 107-42-Sept. 22,2001). 2.2 This Law provided the basis for Rules and Regulations for: a) Airline Stabilization; b) Aviation Insurance; c) Tax Provisions; d) Victims Compensation; and e) Air Transportation Safety. DCCD Doc No. 28 - 2 - 2.3 The Airline Stabilization Act created the legislative vehicle needed to reimburse the air transport industry for their losses of income as a result of the flight interruption due to the 911 attack. -

PORTLAND INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT (PDX) Monthly Traffic Report August, 2008

PORTLAND INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT (PDX) Monthly Traffic Report August, 2008 This Month Calendar Year to Date 2008 2007 %Chg 2008 2007 %Chg Total PDX Flight Operations * 23,458 24,228 -3.2% 175,619 177,612 -1.1% Military 596 304 96.1% 2,797 2,844 -1.7% General Aviation 2,680 3,064 -12.5% 18,010 19,240 -6.4% Hillsboro Airport Operations 24,518 25,136 -2.5% 187,925 161,528 16.3% Troutdale Airport Operations 9,785 10,907 -10.3% 70,577 62,419 13.1% Total System Operations 57,761 60,271 -4.2% 434,121 401,559 8.1% PDX Commercial Flight Operations ** 19,084 19,960 -4.4% 147,954 149,334 -0.9% Cargo 2,464 2,974 -17.1% 20,448 22,322 -8.4% Charter 0 0 44 30 46.7% Major 8,452 8,672 -2.5% 62,830 63,264 -0.7% National 424 372 14.0% 3,060 2,708 13.0% Regional 7,744 7,942 -2.5% 61,572 61,010 0.9% Domestic 18,332 19,190 -4.5% 142,360 143,690 -0.9% International 752 770 -2.3% 5,594 5,644 -0.9% Total Enplaned & Deplaned Passengers 1,433,616 1,460,804 -1.9% 9,991,327 9,776,078 2.2% Charter 0 0 3,271 1,920 70.4% Major 1,017,802 1,077,496 -5.5% 6,955,783 7,067,583 -1.6% National 62,497 59,692 4.7% 454,539 414,932 9.5% Regional 353,317 323,616 9.2% 2,577,734 2,291,643 12.5% Total Enplaned Passengers 716,454 732,664 -2.2% 4,981,517 4,880,384 2.1% Total Deplaned Passengers 717,162 728,140 -1.5% 5,009,810 4,895,694 2.3% Total Domestic Passengers 1,366,154 1,404,415 -2.7% 9,537,487 9,390,729 1.6% Total Enplaned Passengers 683,255 704,644 -3.0% 4,757,367 4,689,043 1.5% Total Deplaned Passengers 682,899 699,771 -2.4% 4,780,120 4,701,686 1.7% Total International Passengers -

Sacramento International Airport Airline Passenger Statistics July 2010

Sacramento International Airport Airline Passenger Statistics July 2010 CURRENT MONTH FISCAL YEAR TO DATE CALENDAR YEAR TO DATE THIS YEAR LAST YEAR % + / ( - ) 2010/11 2009/10 % + / ( - ) 2010 2009 % + / ( - ) Enplaned Domestic Alaska Airlines 25,519 19,792 28.9% 25,519 19,792 28.9% 123,342 106,591 15.7% American Airlines 16,593 16,140 2.8% 16,593 16,140 2.8% 107,297 86,244 24.4% Continental Airlines 14,658 14,288 2.6% 14,658 14,288 2.6% 94,379 98,856 (4.5%) Delta Airlines 36,317 19,603 85.3% 36,317 19,603 85.3% 184,669 117,759 56.8% Frontier Airlines 15,931 12,687 25.6% 15,931 12,687 25.6% 84,949 73,540 15.5% Hawaiian Airlines 7,536 7,616 (1.1%) 7,536 7,616 (1.1%) 49,307 50,683 (2.7%) Horizon Air 13,753 12,058 14.1% 13,753 12,058 14.1% 81,296 71,717 13.4% Jet Blue 10,453 10,669 (2.0%) 10,453 10,669 (2.0%) 64,002 53,048 20.6% Mesa/US Airways Express/YV 753 - 753 - 2,821 - Northwest - 13,184 (100.0%) - 13,184 (100.0%) - 66,533 (100.0%) Skywest/Delta Connection 5,818 5,689 2.3% 5,818 5,689 2.3% 31,982 30,524 4.8% Skywest/United Express 15,635 13,611 14.9% 15,635 13,611 14.9% 107,786 92,425 16.6% Southwest 205,786 214,471 (4.0%) 205,786 214,471 (4.0%) 1,380,693 1,410,965 (2.1%) United Airlines 29,249 32,626 (10.4%) 29,249 32,626 (10.4%) 173,518 199,056 (12.8%) US Airways 25,755 29,462 (12.6%) 25,755 29,462 (12.6%) 129,309 166,358 (22.3%) CHARTER - - - - - - 423,756 421,896 0.4% 423,756 421,896 0.4% 2,615,350 2,624,299 (0.3%) International Mexicana 5,303 6,524 (18.7%) 5,303 6,524 (18.7%) 33,480 32,327 3.6% 5,303 6,524 (18.7%) 5,303 6,524