Coping with Disaster Through Technology: Goodbye

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irish Children's Literature and the Poetics of Memory, 1892-2016

Irish Children’s Literature and the Poetics of Memory, 1892-2016 A Thesis submitted to the School of English at the University of Dublin, Trinity College, for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. February 2019 Rebecca Ann Long I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is entirely my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the Library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library conditions of use and acknowledgement. _________________________________ Rebecca Long February 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY………………………………………………………………………………..i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………....iii INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………....4 CHAPTER ONE: RETRIEVING……………………………………………………………………………29 CHAPTER TWO: RE- TELLING……………………………………………………………………………...…64 CHAPTER THREE: REMEMBERING……………………………………………………………………....106 CHAPTER FOUR: RE- IMAGINING………………………………………………………………………........158 CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………………..……..210 WORKS CITED………………………….…………………………………………………….....226 Summary This thesis explores the recurring patterns of Irish mythological narratives that influence literature produced for children in Ireland following the Celtic Revival and into the twenty- first century. A selection of children’s books published between 1892 and 2016 are discussed with the aim of demonstrating the development of a pattern of retrieving, re-telling, remembering and re-imagining myths -

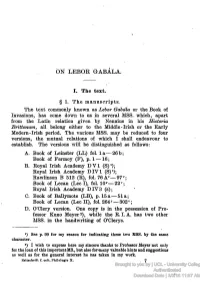

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. the Text

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. The text. § 1. The manuscripts. The text commonly known as Lebor Gabala or the Book of Invasions, has come down to us in several MSS. which, apart from the Latin relation given by Nennius in his Historia Brittomim, all belong either to the Middle-Irish or the Early Modern-Irish period. The various MSS. may be reduced to four versions, the mutual relations of which I shall endeavour to establish. The versions will be distinguished as follows: A. Book of Leinster (LL) fol. la—26b; Book of Fermoy (F), p. 1 —16; B. Royal Irish Academy DVI (S)1); Royal Irish Academy DIV1 (S)1); Rawlinson B 512 (R), fol. 76 Av— 97v; Book of Lecan (Lee I), fol. 10r—22v; Royal Irish Academy DIV3 (s); C. Book of Ballymote (LB), p. 15a—51 a; Book of Lecan (Lee H), fol. 264r—302v; D. OOlery version. One copy is in the possession of Pro- fessor Kuno Meyer2), while the R.I. A. has two other MSS. in the handwriting of O'Clerys. *) See p. 99 for my reason for indicating these two MSS. by the same character. 2) I wish to express here my sincere thanks to Professor Meyer not only for the loan of this important MS., but also formany valuable hints and suggestions as well as for the general interest he has taken in my work. Zeitschrift f. celt. Philologie X. 7 Brought to you by | UCL - University College London Authenticated Download Date | 3/3/16 11:57 AM OS A. G. VAN HAMEL, § 2. -

View / Open Hirao Oregon 0171N 11721.Pdf

BINDING A UNIVERSE: THE FORMATION AND TRANSMUTATIONS OF THE BEST JAPANESE SF (NENKAN NIHON SF KESSAKUSEN) ANTHOLOGY SERIES by AKIKO HIRAO A THESIS Presented to the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts September 2016 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Akiko Hirao Title: Binding a Universe: The Formation and Transmutations of the Best Japanese SF (Nenkan Nihon SF Kessakusen) Anthology Series This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures by: Alisa Freedman Chairperson Glynne Walley Member and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2016. ii © 2016 Akiko Hirao This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (United States) License. iii THESIS ABSTRACT Akiko Hirao Master of Arts Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures September 2016 Title: Binding a Universe: The Formation and Transmutations of the Best Japanese SF (Nenkan Nihon SF Kessakusen) Anthology Series The annual science fiction anthology series The Best Japanese SF started publication in 2009 and showcases domestic writers old and new and from a wide range of publishing backgrounds. Although representative of the second golden era of Japanese science fiction in print in its diversity and with an emphasis on that year in science fiction, as the volumes progress the editors’ unspoken agenda has become more pronounced, which is to create a set of expectations for the genre and to uphold writers Project Itoh and EnJoe Toh as exemplary of this current golden era. -

Working Introduction

University of Pardubice Faculty of Humanities Department of English and American Studies The Influence of the Irish Folk Tales on the Notion of Irishness Thesis Author: Bc. Soň a Šamalíková Supervisor: Mgr. Olga Zderadič ková, M. Litt 2002 Univerzita Pardubice Fakulta humanitních studií Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Vliv irských lidových příběhů na irství Diplomová práce Autor: Bc. Soň a Šamalíková Vedoucí: Mgr. Olga Zderadič ková, M. Litt 2002 Contents Introduction 1 Irishness 3 History 6 Folk tales and the oral tradition in Ireland 15 Fairy tale, myth, legend 17 Irish myths 19 Some Irish myths in detail 23 Irish legends 37 Irish fairy tales 43 Irish folk tales and nationalism 46 Folk tales and Irishness outside Ireland 53 Conclusion 57 Résumé (in Czech) 59 Bibliography 64 Introduction The Irish of the twentieth century are a complex, scattered nation, living not only in Ireland, but also in a part of the United Kingdom--Northern Ireland, as well as in the rest of the country. In large numbers, they can be found in many 0 other countries of the world, mostly the United States of America. The Irish have a long history. Originally a specific Celtic people with a distinctive culture, for many centuries they were exposed to the cultures of numerous invaders, for many centuries they suffered oppression--most painfully under the English overrule. As Professor Falaky Nagy comments, the Irish are ”a people who, for centuries, have been told that their language, their culture, and their religion were worthless and that they should try to be more like the English” [Tay]. -

Kotatsu Japanese Animation Film Festival 2017 in Partnership with the Japan Foundation

Kotatsu Japanese Animation Film Festival 2017 In partnership with the Japan Foundation Chapter - September 29th - October 1st, 2017 Aberystwyth Arts Centre – October 28th, 2017 The Largest Festival of Japanese Animation in Wales Announces Dates, Locations and Films for 2017 The Kotatsu Japanese Animation Festival returns to Wales for another edition in 2017 with audiences able to enjoy a whole host of Welsh premieres, a Japanese marketplace, and a Q&A and special film screening hosted by an important figure from the Japanese animation industry. The festival begins in Cardiff at Chapter Arts on the evening of Friday, September 29th with a screening of Masaaki Yuasa’s film The Night is Short, Walk on Girl (2017), a charming romantic romp featuring a love-sick student chasing a girl through the streets of Kyoto, encountering magic and weird situations as he does so. Festival head, Eiko Ishii Meredith will be on hand to host the opening ceremony and a party to celebrate the start of the festival which will last until October 01st and include a diverse array of films from near-future tales Napping Princess (2017) to the internationally famous mega-hit Your Name (2016). The Cardiff portion of the festival ends with a screening of another Yuasa film, the much-requested Mind Game (2004), a film definitely sure to please fans of surreal and adventurous animation. This is the perfect chance for people to see it on the big-screen since it is rarely screened. A selection of these films will then be screened at the Aberystywth Arts Centre on October 28th as Kotatsu helps to widen access to Japanese animated films to audiences in different locations. -

Espelhos Distorcidos: O Romance at Swim- Two-Birds De Flann O'brien E a Tradição Literária Irlandesa

Universidade de Brasília Instituto de Letras Departamento de Teoria Literária e Literaturas Paweł Hejmanowski Espelhos Distorcidos: o Romance At Swim- Two-Birds de Flann O'Brien e a Tradição Literária Irlandesa Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Literatura para obtenção do título de Doutor, elaborada sob orientação da Profa. Dra. Cristina Stevens. Brasília 2011 IN MEMORIAM PROFESSOR ANDRZEJ KOPCEWICZ 2 Agradeço a minha colega Professora Doutora Cristina Stevens. A conclusão do presente estudo não teria sido possível sem sua gentileza e generosidade. 3 RESUMO Esta tese tem como objeto de análise o romance At Swim-Two-Birds (1939) do escritor irlandês Flann O’Brien (1911-1966). O romance pode ser visto, na perspectiva de hoje, como uma das primeiras tentativas de se implementar a poética de ficção autoconsciente e metaficção na literatura ocidental. Publicado na véspera da 2ª Guerra, o livro caiu no esquecimento até ser re-editado em 1960. A partir dessa data, At Swim-Two-Birds foi adquirindo uma reputação cult entre leitores e despertando o interesse crítico. Ao lançar mão do conceito mise en abyme de André Gide, o presente estudo procura mapear os textos dos quais At Swim-Two-Birds se apropria para refletí-los de forma distorcida dentro de sua própria narrativa. Estes textos vão desde narrativas míticas e históricas, passam pela poesia medieval e vão até os meados do século XX. Palavras-chave: Intertextualidade, Mis en abyme, Literatura e História, Romance Irlandês do séc. XX, Flann O’Brien. ABSTRACT The present thesis analyzes At Swim-Two-Birds, the first novel of the Irish author Flann O´Brien (1911-1966). -

Historias Misteriosas De Los Celtas

Historias misteriosas de los celtas Run Futthark HISTORIAS MISTERIOSAS DE LOS CELTAS A pesar de haber puesto el máximo cuidado en la redacción de esta obra, el autor o el editor no pueden en modo alguno res- ponsabilizarse por las informaciones (fórmulas, recetas, técnicas, etc.) vertidas en el texto. Se aconseja, en el caso de proble- mas específicos —a menudo únicos— de cada lector en particular, que se consulte con una persona cualificada para obtener las informaciones más completas, más exactas y lo más actualizadas posible. DE VECCHI EDICIONES, S. A. Traducción de Nieves Nueno Cobas. Fotografías de la cubierta: arriba, Tumulus gravinis © S. Rasmussen/Diaporama; abajo, Menhir de Poulnabrone, Burren, Irlanda © A. Lorgnier/Diaporama. © De Vecchi Ediciones, S. A. 2012 Diagonal 519-521, 2º - 08029 Barcelona Depósito Legal: B. 15.000-2012 ISBN: 978-17-816-0434-2 Editorial De Vecchi, S. A. de C. V. Nogal, 16 Col. Sta. María Ribera 06400 Delegación Cuauhtémoc México Reservados todos los derechos. Ni la totalidad ni parte de este libro puede reproducirse o trasmitirse por ningún procedimiento electrónico o mecánico, incluyendo fotocopia, grabación magnética o cualquier almacenamiento de información y sistema de recuperación, sin permiso es- crito de DE VECCHI EDICIONES. ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN . 11 LOS ORÍGENES DE LOS CELTAS . 13 Los ligures . 13 Aparición de los celtas . 15 LAS MISTERIOSAS TRIBUS DE LA DIOSA DANA . 19 Los luchrupans . 19 Los fomorianos . 20 Desembarco en Irlanda, «tierra de cólera» . 23 Contra los curiosos fomorianos . 24 Segunda batalla de Mag Tured . 25 Grandeza y decadencia . 27 La presencia de Lug . 29 El misterio de los druidas. -

Downloaded on 2017-02-12T04:28:54Z Mícheál Coimín Agus a Shaothar

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Cork Open Research Archive Title Mícheál Coimín agus a shaothar Author(s) Newman, Stephen Patrick Publication date 2013 Original citation Newman, S. P. 2013. Mícheál Coimín agus a shaothar. PhD Thesis, University College Cork. Type of publication Doctoral thesis Rights © 2013, Stephen P. Newman http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Embargo information No embargo required Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/1461 from Downloaded on 2017-02-12T04:28:54Z Mícheál Coimín agus a Shaothar Stephen Newman Tráchtas PhD Coláiste na hOllscoile, Corcaigh Roinn na Nua-Ghaeilge Iúil 2013 Ceann Roinne: An tOllamh Pádraig Ó Macháin Stiúrthóir Inmheánach: Liam P. Ó Murchú MA 1 Clár Buíochas 4 Réamhrá 5 1 Beatha an Choimínigh 7 2 Saothrú an Phróis san Ochtú hAois Déag 23 3 Eachtra Thoroilbh Mhic Stairn (ETS): Foinsí agus Traidisiún 31 4 Eachtra a Thriúr Mac (ETM) agus Béaloideas an Chláir 57 5 ETS agus ETM: Traidisiún na Lámhscríbhinní 79 Modh Eagarthóireachta 101 Nótaí ar an Teanga 104 ETS agus ETM: Téacs Normálaithe 110 6 Forbhreathnú ar Chorpas Filíochta an Choimínigh 180 7 Filíocht an Choimínigh: Anailís Théamúil agus Stíle 200 Modh Eagarthóireachta 212 ‘A Ainnir mhiochair bhláith’ 214 ‘Sealad dá rabhas a’ taisteal chois abhann’ 216 ‘Idir Sráid Inse is Cluain Ineach’ 218 ‘Dob aisling dom tríom néalta go bhfaca mise an spéirbhean’ 220 ‘Araic gan chrith tugas ar Bhrighid go Boireann ó Chinn Leime’ 222 ‘Bhí bruinneall tséimh is mé i ngrádh’ 226 ‘Aréir tríom néalta is tríom aisling bhréagach’ 228 ‘Cá bhfuil siúd an t-ughdar glic’ 231 ‘Mo chumha is mo chreachsa fear na seanaoise’ 234 Foinsí 236 2 Dearbhú: Dearbhaím gur liom féin an saothar seo agus go bhfuil tagairt cheart chuí déanta agam d’ábhar ar bith a d’úsáid mé as foinsí eile. -

Ashley Woods Art of Metal Gear Solid Free

FREE ASHLEY WOODS ART OF METAL GEAR SOLID PDF Ashley Wood | 120 pages | 21 Apr 2009 | Idea & Design Works | 9781600103629 | English | San Diego, United States Book Review: Ashley Wood's Art of Metal Gear Solid ( edition) | Parka Blogs Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge Ashley Woods Art of Metal Gear Solid. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. From gaming consoles to comic books, Metal Gear Solid has captured the imagination of millions of fans worldwide. And it's little wonder why. The story follows infiltration expert Solid Snake as he attempts to save the world. In addition to showcasing art from Ashley Wood's graphic Ashley Woods Art of Metal Gear Solid adaptations of Metal Gear Solid and Metal Gear Solid: Sons of Liberty, this all- new col From gaming consoles to comic books, Metal Gear Solid has captured the imagination of millions of fans worldwide. Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. More Details Original Title. Other Editions 1. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. Lists with This Book. This book is not yet featured on Listopia. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 4. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. Nov 15, Parka rated it really liked it Shelves: art-books. Ashley Woods Art of Metal Gear Solid pictures at parkablogs. The book I have is a white paperback cover instead of the brown one shown on Amazon left imagenot that it makes any difference. -

IRELAND: a GATHERING of STORIES • Section 1 • the White Trout

Ireland: A Gathering of Sto ries AWAKIN.COM DIGITAL PUBLISHING IRELAND: A GATHERING OF STORIES • Section 1 • The White Trout Story By: A strange thing happened to me when I was in California telling stories in school, way up in Liz Weir, Storyteller Northern California. A woman there told me she had Irish relatives and when I asked her she said and Author she was related to Samuel Lover. I went out and got a copy of my CD, the Glen of Stories and showed her on the notes where it said that The White Trout was collected by Samuel Lover! That’s one of those amazing stories that shows the power of the original world wide web - Storytelling! One of my favourite tales is the White Trout, it’s a legend from County Mayo from Cong which most people know about from The Quiet Man film. It was collected by a man called Samuel Lover in the 1830’s and I first heard it from the telling of Alice Kane. Alice was originally from Belfast and went to Toronto where she became a children’s librarian and then a very well known storyteller. 2 the water and popped it into a pan He cooked it The White Trout . and he cooked it and he cooked it until he thought one side would be done. But when he turned it over, There once was a beautiful lady who lived in a castle there was not a mark on it. He tried the other side. beside a lake. She was engaged to be married to a He cooked it and he cooked it but again there was king’s son, but a month before the wedding her no mark or burn. -

Dieux Celtes Pour Les Assimiler Et Cette Assimilation Nous Est Parvenue

MAJ 26/06/2002 Imprimé le jj/12/a LES DIEUX, LA MYTHOLOGIE ET LA RELIGION CELTE (celte, gaulois, irlandais, gallois) Sommaire Mythologie celte________________________ 6 Andarta (gaule) ________________________9 Introduction ____________________________ 6 Andrasta (gaule)________________________9 L'Origine de la mythologie Celte ___________ 6 Andraste (breto-celte)___________________10 Transmission des mythes__________________ 6 Anextiomarus (breto-celte) ______________10 Textes mythologiques Irlandais ________________6 Angus (irlande) _______________________10 Abandinus (romano-celte)________________ 7 Angus of the brugh (irlande)_____________10 Abarta (irlande) ________________________ 7 Annwn (galles) ________________________10 Abelio (gaule)__________________________ 7 Anu (irlande) _________________________10 Abnoba (romano-celte) __________________ 7 Aobh (irlande) ________________________10 Adraste (breto-celte)_____________________ 7 Aoi Mac Ollamain (irlande) _____________10 Adsullata (celte) ________________________ 8 Aoibhell (irlande) ______________________10 Aed (irlande) __________________________ 8 Aonghus (irlande) _____________________10 Aenghus (irlande) ______________________ 8 Aranrhod (galles) ______________________10 Aengus (irlande) _______________________ 8 Arawn (galles) ________________________10 Aericura (romano-celte) _________________ 8 Arduinna (gaule) ______________________10 Aes Sidhe (irlande)______________________ 8 Arianrhod (galles) _____________________10 Afagddu (galles)________________________ 8 Arnemetia -

Encyclopedia of CELTIC MYTHOLOGY and FOLKLORE

the encyclopedia of CELTIC MYTHOLOGY AND FOLKLORE Patricia Monaghan The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore Copyright © 2004 by Patricia Monaghan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Monaghan, Patricia. The encyclopedia of Celtic mythology and folklore / Patricia Monaghan. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-4524-0 (alk. paper) 1. Mythology, Celtic—Encyclopedias. 2. Celts—Folklore—Encyclopedias. 3. Legends—Europe—Encyclopedias. I. Title. BL900.M66 2003 299'.16—dc21 2003044944 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by Erika K. Arroyo Cover design by Cathy Rincon Printed in the United States of America VB Hermitage 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. CONTENTS 6 INTRODUCTION iv A TO Z ENTRIES 1 BIBLIOGRAPHY 479 INDEX 486 INTRODUCTION 6 Who Were the Celts? tribal names, used by other Europeans as a The terms Celt and Celtic seem familiar today— generic term for the whole people.