The Emancipation of South America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

San Martín: Argentine Patriot, American Liberator

UNIVERSITY OF LONDON INSTITUTE OF LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES OCCASIONAL PAPERS No. 25 San Martín: Argentine Patriot, American Liberator John Lynch SAN MARTíN: ARGENTINE PATRIOT, AMERICAN LIBERATOR John Lynch Institute of Latin American Studies 31 Tavistock Square London WC1H 9HA The Institute of Latin American Studies publishes as Occasional Papers selected seminar and conference papers and public lectures delivered at the Institute or by scholars associated with the work of the Institute. John Lynch is Emeritus Professor of Latin American History in the University of London, where he has spent most of his academic career, first at University College, then from 1974 to 1987 as Director of the Institute of Latin American Studies. The main focus of his work has been Spanish America in the period 1750–1850. Occasional Papers, New Series 1992– ISSN 0953 6825 © Institute of Latin American Studies University of London, 2001 San Martín: Argentine Patriot, American Liberator 1 José de San Martín, one of the founding fathers of Latin America, comparable in his military and political achievements with Simón Bolívar, and arguably incomparable as a model of disinterested leadership, is known to history as the hombre necesario of the American revolution. There are those, it is true, who question the importance of his career and reject the cult of the hero. For them the meaning of liberation is to be found in the study of economic struc- tures, social classes and the international conjuncture, not in military actions and the lives of liberators. In this view Carlyle’s discourse on heroes is a mu- seum piece and his elevation of heroes as the prime subject of history a misconception. -

Rc: 79917 - Issn: 2448-0959

Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento - RC: 79917 - ISSN: 2448-0959 https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/sem-categoria/the-reason The reason for the state ARTÍCULO ORIGINAL PEDROSO, Nilda Da Conceição [1] PEDROSO, Nilda Da Conceição. The reason for the state. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 05, Ed. 10, Vol. 15, 18-33. October 2020. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/historia-es/la-razon, DOI: 10.32749/nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/history-is/la-reason Summary With this work we intend to study the Folders of the historical collection of the national archive. They contain the Captainular Acts of the Meetings of the National Assumption Lobby in the period 1805 and 1806. Our intention is to demonstrate, through these demands, and to expose an insipient and colonized Assumption, but hardworking, politicized and developing. Demonstrate the same, the activity of a state apparatus that in the past played an important role together with the people: the Cabildo. On the other hand we intend to contribute to clarify points of questions taken to centuries and that with this monographic work are alls of the past and brought to the historical present. Key words: Folders, chapter minutes, lobbying, Assumption. 1. INTRODUCTION To the team of students of the ONE Master's Course, it was given to present a work, that of doing a study of the Chapter Acts contained in a folder corresponding to the period of a full decade: from 1801 to 1811. These are the years that anticipated the most important event for the Republic of Paraguay: its Independence.From these years it was up to us to do the study of the years 1805 and 1806. -

The Translation Process Series Multiple Perspectives from Teaching to Professional Practice

The Translation Process Series Multiple perspectives from teaching to professional practice Mariona Sabaté-Carrové and Lorena Baudo (Eds.) Volume 1 The Translation Process Series Multiple perspectives from teaching to professional practice Mariona Sabaté-Carrové and Lorena Baudo (Eds.) Edicions de la Universitat de Lleida Lleida, 2021 Edited by: Edicions de la Universitat de Lleida, 2021 Layout: Edicions i Publicacions de la Universitat de Lleida Cover photo: Leone, Ulrike (2017). Gear. Pixabay. https://pixabay.com/es/users/ ulleo-1834854/. Date of last visit: May 7th, 2021 ISBN 978-84-9144-281-3 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommer- cial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, DOI 10.21001/translation_process_series_volume1.2021 visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/. Table of contents Foreword ...................................................................................................................7 The editors PAPERS Two teaching experiences in translation: Aiming to enrich differing university programs through an integrated and cross-cultural project ..............19 Lorena Guadalupe Baudo and Mariona Sabaté-Carrové Everyday language in Harold Pinter’s The Applicant. Theatrical translation challenges in online classroom teaching ............................................................29 Mariazell-Eugènia Bosch Fábregas Preconceptions from pre-professionals about MTPE ...............................................41 Laura Bruno, Antonio -

The Mexican General Officer Corps in the US

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Latin American Studies ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-1-2011 Valor Wrought Asunder: The exM ican General Officer Corps in the U.S.-Mexican War, 1846-1847. Javier Ernesto Sanchez Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ltam_etds Recommended Citation Sanchez, Javier Ernesto. "Valor Wrought Asunder: The exM ican General Officer Corps in the U.S.-Mexican War, 1846-1847.." (2011). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ltam_etds/3 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Latin American Studies ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Javier E. Sánchez Candidate Latin-American Studies Department This thesis is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Thesis Committee: L.M. García y Griego, Chairperson Teresa Córdova Barbara Reyes i VALOR WROUGHT ASUNDER: THE MEXICAN GENERAL OFFICER CORPS IN THE U.S.-MEXICAN WAR, 1846 -1847 by JAVIER E. SANCHEZ B.B.A., BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, UNIVERSITY OF NEW MEXICO 2009 THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December 2011 ii VALOR WROUGHT ASUNDER: THE MEXICAN GENERAL OFFICER CORPS IN THE U.S.-MEXICAN WAR, 1846-1847 By Javier E. Sánchez B.A., Business Administration, University of New Mexico, 2008 ABSTRACT This thesis presents a reappraisal of the performance of the Mexican general officer corps during the U.S.-Mexican War, 1846-1847. -

Proceedings First Annual Palo Alto Conference

PROCEEDINGS OF THE FIRST ANNUAL PALO ALTO CONFERENCE An International Conference on the Mexican-American War and its Causes and Consequences with Participants from Mexico and the United States. Brownsville, Texas, May 6-9, 1993 Palo Alto Battlefield National Historic Site Southwest Region National Park Service I Cover Illustration: "Plan of the Country to the North East of the City of Matamoros, 1846" in Albert I C. Ramsey, trans., The Other Side: Or, Notes for the History of the War Between Mexico and the I United States (New York: John Wiley, 1850). 1i L9 37 PROCEEDINGS OF THE FIRST ANNUAL PALO ALTO CONFERENCE Edited by Aaron P. Mahr Yafiez National Park Service Palo Alto Battlefield National Historic Site P.O. Box 1832 Brownsville, Texas 78522 United States Department of the Interior 1994 In order to meet the challenges of the future, human understanding, cooperation, and respect must transcend aggression. We cannot learn from the future, we can only learn from the past and the present. I feel the proceedings of this conference illustrate that a step has been taken in the right direction. John E. Cook Regional Director Southwest Region National Park Service TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction. A.N. Zavaleta vii General Mariano Arista at the Battle of Palo Alto, Texas, 1846: Military Realist or Failure? Joseph P. Sanchez 1 A Fanatical Patriot With Good Intentions: Reflections on the Activities of Valentin GOmez Farfas During the Mexican-American War. Pedro Santoni 19 El contexto mexicano: angulo desconocido de la guerra. Josefina Zoraida Vazquez 29 Could the Mexican-American War Have Been Avoided? Miguel Soto 35 Confederate Imperial Designs on Northwestern Mexico. -

A Tribute to "La Capitana", the Afro-Argentine Who Fought for Independence

HISTORY A TRIBUTE TO "LA CAPITANA", THE AFRO-ARGENTINE WHO FOUGHT FOR INDEPENDENCE María Remedios del Valle, called "La Capitana" and "The Mother of the Nation". Illustration by Eleonora Kortsarz. The new century was just beginning and the According to the census data carried out by Juan atmosphere in the homeland was one of José de Vértiz y Salcedo in 1778, Afro- independence. She, "La Capitana", did not descendants in the city of Buenos Aires made up hesitate to defend her land in 1807, when the 30% of the total population, that barely exceeded English invaded the coasts of Buenos Aires for 24,000 inhabitants. Most of them were the second time. That was when María Remedios concentrated in the neighborhoods of San Telmo del Valle began to write her own story of liberation and Monserrat, where they created handicrafts and bravery. for sale. The rest of this population was registered mainly in the provinces with high Registered in the parish records as "parda" agricultural production, such as Santiago del (brown-skinned), as established by the colonial Estero, Catamarca, Córdoba and Salta, among caste system, this woman defied a destiny of others. humiliation, misery and oppression, to become an Independence heroine. She was born in the city of María Remedios del Valle was part of a group in Buenos Aires in 1766 or 1767, and according to which many were reduced to servitude, while documents, she had dark skin, her origins were others managed to buy their freedom or escaped. African, and, in addition, she was a woman. Many played an active part against the English 1 HISTORY city, until her luck turned in the mid-1820s, when THE MAJORITY OF AFRO- General Juan José Viamonte recognized her begging in the streets. -

Tyranny Or Victory! Simón Bolívar's South American Revolt

ODUMUNC 2018 Issue Brief Tyranny or Victory! Simón Bolívar’s South American Revolt by Jackson Harris Old Dominion University Model United Nations Society of the committee, as well as research, all intricacies involved in the committee will be discussed in this outline. The following sections of this issue brief will contain a topical overview of the relevant history of Gran Colombia, Simón Bolívar, and Spanish-American colonial relations, as well as an explanation of the characters that delegates will be playing. This guide is not meant to provide a complete understanding of the history leading up to the committee, rather to provide a platform that will be supplemented by personal research. While there are a number of available online sources the Crisis Director has provided the information for a group of helpful books to use at the delegate’s discretion. The legacy of Simón Bolívar, the George Washington of South America, is anything but historical. His life stands at the center of contemporary South America.1 Any doubt about his relevance was eliminated on 16 July 2010 when Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez presided at the exhumation of Bolívar’s remains.2 Pieces of the skeleton were El Libertador en traje de campaña, by Arturo Michelena 1985, Galería de Arte Nacional 1 Gerhard Straussmann Masur, ‘Simón Bolívar: Venezuelan soldier and statesman’, Encyclopædia Britannica, n.d., https://www.britannica.com/biography/Simo n-Bolivar ; and Christopher Minster, FORWARD ‘Biography of Simon Bolivar: Liberator of ¡Bienvenidos delegados! Welcome to the South America’, ThoughtCo., 8 September Tyranny or Victory! Simón Bolívar’s 2017, South American Revolt crisis committee! https://www.thoughtco.com/biography-of- In order to allow delegates to familiarize simon-bolivar-2136407 2 Thor Halvorssen, ‘Behind exhumation of themselves with the rules and procedures Simon Bolivar is Hugo Chavez's warped Tyranny or Victory! Simón Bolívar’s South American Revolt removed for testing. -

The Diary of Heinrich Witt

The Diary of Heinrich Witt Volume 9 Edited by Ulrich Mücke LEIDEN | BOSTON Ulrich Muecke - 9789004307247 Downloaded from Brill.com10/10/2021 05:09:24AM via free access [1] Volume IX. [2] Commenced in Lima, on the 26th April 1880, by Mr. Neat Ladd Residence in Lima. Thursday, 13th of March 1879. A few days back I lent Alejandro, of my own funds, S15,000, at 1% monthly, upon some ground in Miraflores, measuring 54,000 square varas, which some time ago he had bought from Domingo Porta. At 2 o’clock I went by the Oroya train to Callao; when there, accompanied by Mr. Higginson, to the store of Grace Brothers & Co., to purchase some duck, “lona”, which I required for the curtains, or “velas”, in my Chorrillos rancho, those which I had bought several years back, at the same time as the rancho itself, having become torn and useless; various samples were shewn me, however I made no purchase, because, as the salesman told me, of the quality best adapted, they had several bales aboard a vessel in the bay, from which they could not be landed for eight or ten days. Enriqueta was again ill with migraine, and kept her bed; neither did I go in the evening to the salita, where Garland played rocambor with his friends. Friday, 14th of March 1879. Ricardo read me an article from the Cologne Gazette which said that the plague which had committed great ravages mostly in the vicinity of Astrakhan, owed its origin to the clothes and other articles, which, torn off on the field of battle from half putrefied corpses, had been carried by the Cossacks to their homes on their return from the late Turco- Russian war. -

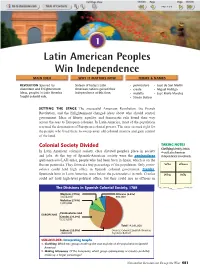

Latin American Peoples Win Independence MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES

1 Latin American Peoples Win Independence MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES REVOLUTION Spurred by Sixteen of today’s Latin • peninsulare •José de San Martín discontent and Enlightenment American nations gained their • creole •Miguel Hidalgo ideas, peoples in Latin America independence at this time. •mulatto •José María Morelos fought colonial rule. • Simón Bolívar SETTING THE STAGE The successful American Revolution, the French Revolution, and the Enlightenment changed ideas about who should control government. Ideas of liberty, equality, and democratic rule found their way across the seas to European colonies. In Latin America, most of the population resented the domination of European colonial powers. The time seemed right for the people who lived there to sweep away old colonial masters and gain control of the land. Colonial Society Divided TAKING NOTES Clarifying Identify details In Latin American colonial society, class dictated people’s place in society about Latin American and jobs. At the top of Spanish-American society were the peninsulares independence movements. (peh•neen•soo•LAH•rehs), people who had been born in Spain, which is on the Iberian peninsula. They formed a tiny percentage of the population. Only penin- WhoWh WhereWh sulares could hold high office in Spanish colonial government. Creoles, Spaniards born in Latin America, were below the peninsulares in rank. Creoles When Why could not hold high-level political office, but they could rise as officers in The Divisions in Spanish Colonial Society, 1789 Mestizos (7.3%) Africans (6.4%) 1,034,000 902,000 Mulattos (7.6%) 1,072,000 Peninsulares and EUROPEANS Creoles (22.9%) {3,223,000 Total 14,091,000 Indians (55.8%) Source: Colonial Spanish America, 7,860,000 by Leslie Bethell SKILLBUILDER: Interpreting Graphs 1. -

The Role of Science in Latin American Independence Revolution

The Role of Science in Latin American Independence Revolution Song xia [email protected] Institute of Latin American Studies Chinese Academy of Social Sciences Abstract In the past, historians tended to think that the Latin American independence revolution was just a political revolution or political struggle. But to my opinion, the independent revolution in Latin America is above all a revolution about scientific thoughts and knowledge. Along with the armed revolution, another revolution took place in the heart of Latin American society. This revolution was intellectual in nature and led to the conception of the full sovereignty of nations. But this great role science played in the independence revolution was little known until now. Since the 17th century, especially from the 18th century on, scientists and historians of science started to use the concept of revolution to describe the progress of science. Just as Joseph Priestley pointed out, when referring to the times of his life (18th century), that it was both a time of a philosophy or scientific revolution and also a national revolution age. It was clearly a period of crisis and instability in the 17th and 18th centuries, and there seemed a universal revolution, and events in different regions are only particular manifestation of this revolution. Occurred in the late 18th and early 19th century, American War of Independence, the French Revolution and the independence of Iberian-America's revolutionary war was precisely accompanied by a second scientific revolution. I divide this article into three parts. In the first part I mainly discuss the historical background of science in Spanish America. -

An Introduction to Contemporary Latin America Flores, Fernando

From Las Casas to Che : An Introduction to Contemporary Latin America Flores, Fernando 2007 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Flores, F. (2007). From Las Casas to Che : An Introduction to Contemporary Latin America. Lund University. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 From Las Casas to Che Omslagsbild: Las, Casas/Che Guevara © Maria Crossa, 2007 From Las Casas to Che An Introduction to Contemporary Latin America Fernando Flores Morador Lund University 2007 Department of History of Science and Ideas at Lund University, Biskopsgatan -

Socio-Racial Sensibilities Towards Coloured Subaltern Sectors in the Spanish Atlantic

Culture & History Digital Journal 4(2) December 2015, e011 eISSN 2253-797X doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3989/chdj.2015.011 Socio-Racial Sensibilities towards coloured subaltern sectors in the Spanish Atlantic Alejandro E. Gómez Maître de conferences Université Lille 3, 3 Rue du Barreau, 59650 Villeneuve-d’Ascq, France e-mail: [email protected] Submitted: 2 January 2015. Accepted: 28 February 2015 ABSTRACT: This article studies from a longue durée perspective the articulation of anti-slavery sentiments and other socio-racial sensibilities within the Spanish Atlantic, from the first theological criticisms of the 16th century to the efforts to abolish slavery in Cuba, Puerto Rico and Spain, in the second half of the 19th century. We focus on the most significant cases of individuals who shared a white identity and who advocated against slavery, slave trade and socio-racial discrimination of Free Coloureds. We argue that the many egalitarian proposals made during the Spanish American revolutions and at the Cortes of Cádiz represent a second golden moment (after the ‘Mulatto Affaire’ dur- ing the French Revolution) in the struggle for the granting of political equality to subaltern sectors the Atlantic World. In the end, we expect to provide a clearer picture of how the socio-racial sensibilities contributed to acceler- ate, or to postpone, the introduction of abolitionist or equalitarian measures vis-à-vis the coloured subaltern sectors in the Spanish Atlantic in the Late Modern Age. KEYWORDS: Abolitionism; slavery; citizenship; race; revolutions; liberalism; emotions; Atlantic World. Citation / Cómo citar este artículo: Gómez, Alejandro E. (2015). “Socio-Racial Sensibilities towards coloured subaltern sectors in the Spanish Atlantic”.