Independence Movements in the Americas During the Age of Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brown, M. D. (2015). the Global History of Latin America. Journal of Global History, 10(3), 365-386

Brown, M. D. (2015). The global history of Latin America. Journal of Global History, 10(3), 365-386. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1740022815000182 Peer reviewed version Link to published version (if available): 10.1017/S1740022815000182 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ The Global History of Latin America Submission to Journal of Global History, 30 October 2014, revised 1 June 2015 [12,500 words] Dr. Matthew Brown Reader in Latin American Studies, University of Bristol 15 Woodland Road, Bristol, BS8 1TE [email protected] Abstract [164 words] The global history of Latin America This article explains why historians of Latin America have been disinclined to engage with global history, and how global history has yet to successfully integrate Latin America into its debates. It analyses research patterns and identifies instances of parallel developments in the two fields, which have operated until recently in relative isolation from one another, shrouded and disconnected. It outlines a framework for engagement between Latin American history and global history, focusing particularly on the significant transformations of the understudied nineteenth-century. It suggests that both global history and Latin American history will benefit from recognition of the existing work that has pioneered a path between the two, and from enhanced and sustained dialogue. -

The Challenges of Cultural Relations Between the European Union and Latin America and the Caribbean

The challenges of cultural relations between the European Union and Latin America and the Caribbean Lluís Bonet and Héctor Schargorodsky (Eds.) The challenges of cultural relations between the European Union and Latin America and the Caribbean Lluís Bonet and Héctor Schargorodsky (Eds.) Title: The Challenges of Cultural Relations between the European Union and Latin America and the Caribbean Editors: Lluís Bonet and Héctor Schargorodsky Publisher: Quaderns Gescènic. Col·lecció Quaderns de Cultura n. 5 1st Edition: August 2019 ISBN: 978-84-938519-4-1 Editorial coordination: Giada Calvano and Anna Villarroya Design and editing: Sistemes d’Edició Printing: Rey center Translations: María Fernanda Rosales, Alba Sala Bellfort, Debbie Smirthwaite Pictures by Lluís Bonet (pages 12, 22, 50, 132, 258, 282, 320 and 338), by Shutterstock.com, acquired by OEI, original photos by A. Horulko, Delpixel, V. Cvorovic, Ch. Wollertz, G. C. Tognoni, LucVi and J. Lund (pages 84, 114, 134, 162, 196, 208, 232 and 364) and by www.pixnio.com, original photo by pics_pd (page 386). Front cover: Watercolor by Lluís Bonet EULAC Focus has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 693781. Giving focus to the Cultural, Scientific and Social Dimension of EU - CELAC relations (EULAC Focus) is a research project, funded under the EU’s Horizon 2020 programme, coordinated by the University of Barcelona and integrated by 18 research centers from Europe and Latin America and the Caribbean. Its main objective is that of «giving focus» to the Cultural, Scientific and Social dimension of EU- CELAC relations, with a view to determining synergies and cross-fertilization, as well as identifying asymmetries in bi-lateral and bi-regional relations. -

US Historians of Latin America and the Colonial Question

UC Santa Barbara Journal of Transnational American Studies Title Imperial Revisionism: US Historians of Latin America and the Spanish Colonial Empire (ca. 1915–1945) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/30m769ph Journal Journal of Transnational American Studies, 5(1) Author Salvatore, Ricardo D. Publication Date 2013 DOI 10.5070/T851011618 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/30m769ph#supplemental Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Imperial Revisionism: US Historians of Latin America and the Spanish Colonial Empire (ca. 1915–1945) RICARDO D. SALVATORE Since its inception, the discipline of Hispanic American history has been overshadowed by a dominant curiosity about the Spanish colonial empire and its legacy in Latin America. Carrying a tradition established in the mid-nineteenth century, the pioneers of the field (Bernard Moses and Edward G. Bourne) wrote mainly about the experience of Spanish colonialism in the Americas. The generation that followed continued with this line of inquiry, generating an increasing number of publications about the colonial period.1 The duration, organization, and principal institutions of the Spanish empire have drawn the attention of many historians who did their archival work during the early twentieth century and joined history departments of major US universities after the outbreak of World War I. The histories they wrote contributed to consolidating the field of Hispanic American history in the United States, producing important findings in a variety of themes related to the Spanish empire. It is my contention that this historiography was greatly influenced by the need to understand the role of the United States’ policies in the hemisphere. -

1 LAH 6934: Colonial Spanish America Ida Altman T 8-10

LAH 6934: Colonial Spanish America Ida Altman T 8-10 (3-6 p.m.), Keene-Flint 13 Office: Grinter Rm. 339 Email: [email protected] Hours: Th 10-12 The objective of the seminar is to become familiar with trends and topics in the history and historiography of early Spanish America. The field has grown rapidly in recent years, and earlier pioneering work has not been superseded. Our approach will take into account the development of the scholarship and changing emphases in topics, sources and methodology. For each session there are readings for discussion, listed under the weekly topic. These are mostly journal articles or book chapters. You will write short (2-3 pages) response papers on assigned readings as well as introducing them and suggesting questions for discussion. For each week’s topic a number of books are listed. You should become familiar with most of this literature if colonial Spanish America is a field for your qualifying exams. Each student will write two book reviews during the semester, to be chosen from among the books on the syllabus (or you may suggest one). The final paper (12-15 pages in length) is due on the last day of class. If you write a historiographical paper it should focus on the most important work on the topic rather than being bibliographic. You are encouraged to read in Spanish as well as English. For a fairly recent example of a historiographical essay, see R. Douglas Cope, “Indigenous Agency in Colonial Spanish America,” Latin American Research Review 45:1 (2010). You also may write a research paper. -

History - Latin America & Caribbean (Hisl)

2021-2022 1 HISTORY - LATIN AMERICA & CARIBBEAN (HISL) HISL 1140 Freshman Seminar-Lat Amr (3) Freshman Seminar in Latin American History. HISL 1500 Special Topics (3) Courses offered by visiting professors or permanent faculty. For description, consult the department. Notes: For special offering, see the Schedule of Classes. HISL 1710 Intro Latin Americn Hist (3) Main currents of Latin American civilization from the European conquest to the present, with special attention to the historical background of present controversies. HISL 1720 Intro Caribbean History (3) This course provides a survey introduction to the history of the Caribbean basin including the island territories located in the Caribbean Sea as well as those Atlantic islands and regions of mainland Central and South America which have shared similar historical experience with the Caribbean basin. The course covers the period from the mid fifteenth century immediately before European arrival up to the present day. Major themes will include European conquest and colonialism, African enslavement, East Asian immigration, the development of multi ethnic societies, U.S. relations with the Caribbean region, and the role of tourism in recent Caribbean history. HISL 1890 Service Learning (0-1) Maximum Hours: 99 HISL 1910 Special Topics (3) Courses offered by visiting professors or permanent faculty. For description, consult the department. Notes: For special offering, see the Schedule of Classes. Course may be repeated unlimited times for credit. Course Limit: 99 HISL 2100 Latin Am Independence Movement (3) Independence movements swept the Americas in an age of radical social and political transformations. New ideas about individual rights, democracy, the public sphere, and equality shaped debates across the region. -

The Invention of Latin America: a Transnational History of Anti-Imperialism, Democracy, and Race

The Invention of Latin America: A Transnational History of Anti-Imperialism, Democracy, and Race MICHEL GOBAT WITH THE PUBLICATION OF Benedict Anderson’s Imagined Communities in 1983, it has become commonplace among scholars to view nations no longer as things natural but as historical inventions.1 Far less ink has been spilled concerning the formation of larger geopolitical entities such as continents. Many still take their origins for granted. Yet as some scholars have shown, the terms “Africa,” “America,” “Asia,” and “Europe” resulted from complex historical processes.2 The concept of the con- tinent emerged in ancient Greece and guided Europeans in their efforts to dominate other areas of the world, especially from the fourteenth century onward. Non-Eu- ropean societies certainly conceptualized their own geopolitical spaces, but the mas- sive spread of European imperialism in the nineteenth century ensured that the European schema of dividing the world into continents would predominate by the twentieth century.3 The invention of “Latin America” nevertheless reveals that contemporary con- tinental constructs were not always imperial products. True, many scholars assume that French imperialists invented “Latin America” in order to justify their country’s occupation of Mexico (1862–1867).4 And the idea did stem from the French concept of a “Latin race,” which Latin American e´migre´s in Europe helped spread to the other side of the Atlantic. But as Arturo Ardao, Miguel Rojas Mix, and Aims IamverygratefultoVı´ctor Hugo Acun˜a Ortega, Laura Gotkowitz, Agnes Lugo-Ortiz, Diane Miliotes, Jennifer Sessions, the AHR editors, and the anonymous reviewers for their extremely helpful comments. -

Tyranny Or Victory! Simón Bolívar's South American Revolt

ODUMUNC 2018 Issue Brief Tyranny or Victory! Simón Bolívar’s South American Revolt by Jackson Harris Old Dominion University Model United Nations Society of the committee, as well as research, all intricacies involved in the committee will be discussed in this outline. The following sections of this issue brief will contain a topical overview of the relevant history of Gran Colombia, Simón Bolívar, and Spanish-American colonial relations, as well as an explanation of the characters that delegates will be playing. This guide is not meant to provide a complete understanding of the history leading up to the committee, rather to provide a platform that will be supplemented by personal research. While there are a number of available online sources the Crisis Director has provided the information for a group of helpful books to use at the delegate’s discretion. The legacy of Simón Bolívar, the George Washington of South America, is anything but historical. His life stands at the center of contemporary South America.1 Any doubt about his relevance was eliminated on 16 July 2010 when Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez presided at the exhumation of Bolívar’s remains.2 Pieces of the skeleton were El Libertador en traje de campaña, by Arturo Michelena 1985, Galería de Arte Nacional 1 Gerhard Straussmann Masur, ‘Simón Bolívar: Venezuelan soldier and statesman’, Encyclopædia Britannica, n.d., https://www.britannica.com/biography/Simo n-Bolivar ; and Christopher Minster, FORWARD ‘Biography of Simon Bolivar: Liberator of ¡Bienvenidos delegados! Welcome to the South America’, ThoughtCo., 8 September Tyranny or Victory! Simón Bolívar’s 2017, South American Revolt crisis committee! https://www.thoughtco.com/biography-of- In order to allow delegates to familiarize simon-bolivar-2136407 2 Thor Halvorssen, ‘Behind exhumation of themselves with the rules and procedures Simon Bolivar is Hugo Chavez's warped Tyranny or Victory! Simón Bolívar’s South American Revolt removed for testing. -

The Diary of Heinrich Witt

The Diary of Heinrich Witt Volume 9 Edited by Ulrich Mücke LEIDEN | BOSTON Ulrich Muecke - 9789004307247 Downloaded from Brill.com10/10/2021 05:09:24AM via free access [1] Volume IX. [2] Commenced in Lima, on the 26th April 1880, by Mr. Neat Ladd Residence in Lima. Thursday, 13th of March 1879. A few days back I lent Alejandro, of my own funds, S15,000, at 1% monthly, upon some ground in Miraflores, measuring 54,000 square varas, which some time ago he had bought from Domingo Porta. At 2 o’clock I went by the Oroya train to Callao; when there, accompanied by Mr. Higginson, to the store of Grace Brothers & Co., to purchase some duck, “lona”, which I required for the curtains, or “velas”, in my Chorrillos rancho, those which I had bought several years back, at the same time as the rancho itself, having become torn and useless; various samples were shewn me, however I made no purchase, because, as the salesman told me, of the quality best adapted, they had several bales aboard a vessel in the bay, from which they could not be landed for eight or ten days. Enriqueta was again ill with migraine, and kept her bed; neither did I go in the evening to the salita, where Garland played rocambor with his friends. Friday, 14th of March 1879. Ricardo read me an article from the Cologne Gazette which said that the plague which had committed great ravages mostly in the vicinity of Astrakhan, owed its origin to the clothes and other articles, which, torn off on the field of battle from half putrefied corpses, had been carried by the Cossacks to their homes on their return from the late Turco- Russian war. -

Development of the Latin American Feeling of Distrust Toward

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1947 Development of the Latin American Feeling of Distrust Toward the United States, as Exemplified By the Works of Latin American Essayists Ann Parker Loyola University Chicago Recommended Citation Parker, Ann, "Development of the Latin American Feeling of Distrust Toward the United States, as Exemplified By the Works of Latin American Essayists" (1947). Master's Theses. Paper 313. http://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/313 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1947 Ann Parker f I DEVELOP!SN'I' OF T!Li: LATIN M!illRIC.ilN FE:ELING OF DISTmJST TOWARD THE UNITED STl1.Tl!S, AS EXEI'Il'TLIFIED EY ·THE WORKS OF LATIN s~ICAN ESSAYISTS By ANN PA:RR:ER A TID!SIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQ,UIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN LOYO)A UNIVERSITY • JUNE 1947 V I T A Ann Parker was born in Chicago, Illinois, January 14, 1917. Shere ceived a teachers certificate from Chicago Normal College, Chicago, Illin ois, June, 1937. The Bachelor of Philosophy degree was conferred by De Paul University, Chicago, Illinois, June, 1941. Since March, 1942, the writer has been a student in the Department of Spanish at Loyola Universi ty. -

Latin American Peoples Win Independence MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES

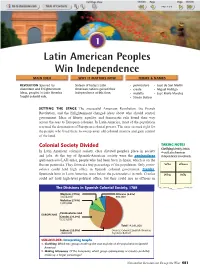

1 Latin American Peoples Win Independence MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES REVOLUTION Spurred by Sixteen of today’s Latin • peninsulare •José de San Martín discontent and Enlightenment American nations gained their • creole •Miguel Hidalgo ideas, peoples in Latin America independence at this time. •mulatto •José María Morelos fought colonial rule. • Simón Bolívar SETTING THE STAGE The successful American Revolution, the French Revolution, and the Enlightenment changed ideas about who should control government. Ideas of liberty, equality, and democratic rule found their way across the seas to European colonies. In Latin America, most of the population resented the domination of European colonial powers. The time seemed right for the people who lived there to sweep away old colonial masters and gain control of the land. Colonial Society Divided TAKING NOTES Clarifying Identify details In Latin American colonial society, class dictated people’s place in society about Latin American and jobs. At the top of Spanish-American society were the peninsulares independence movements. (peh•neen•soo•LAH•rehs), people who had been born in Spain, which is on the Iberian peninsula. They formed a tiny percentage of the population. Only penin- WhoWh WhereWh sulares could hold high office in Spanish colonial government. Creoles, Spaniards born in Latin America, were below the peninsulares in rank. Creoles When Why could not hold high-level political office, but they could rise as officers in The Divisions in Spanish Colonial Society, 1789 Mestizos (7.3%) Africans (6.4%) 1,034,000 902,000 Mulattos (7.6%) 1,072,000 Peninsulares and EUROPEANS Creoles (22.9%) {3,223,000 Total 14,091,000 Indians (55.8%) Source: Colonial Spanish America, 7,860,000 by Leslie Bethell SKILLBUILDER: Interpreting Graphs 1. -

An Overview of the Economy of the Viceroyalty of Peru, 1542-1600

1 | Ezra’s Archives Spanish Colonial Economies: An Overview of the Economy of the Viceroyalty of Peru, 1542-1600 Denis Hurley The consolidation of Spanish geopolitical and military preeminence in Central and South America (despite Portuguese pretensions in Brazil) during the 16th century coincided with a period of rapid economic growth in Spain’s colonies. The Viceroyalty of Peru,1 established in 1542, was an exceptional example of Spanish colonial economic dynamism. From the region’s initial settlement, the mining of precious metals, the encomienda system, and the enslavement and exploitation of Native peoples, provided a solid, if somewhat undiversified, foundation for the young Peruvian economy. The Spanish crown’s jealous possession of the mineral wealth in the New World colonies engendered a singularly invasive and mercantilist colonial economic policy. As a result, Spanish policy profoundly influenced the development of the Peruvian economy, molding its construction to maximize the colony’s utility to the mother country. Spanish policy rarely exerted the full and intended impact envisaged by Spanish administrators, but the effects were sufficient to leave a debilitating legacy of dependence on primary product export, vastly unequal land distribution, and significant socio-economic stratification, often along racial lines. Eventually, the inflexibility of the Peruvian economy, finite amounts of precious metals, and stifling Spanish policy brought economic stagnation and discontent to the colony while bullion imports 1 Note: when I refer to “Peru” I am referring to the geographical region known as the Viceroyalty of Peru during the 16th century not the contemporary state named Peru. I will use Peru and Viceroyalty of Peru interchangeably. -

History of Modern Latin America

History of Modern Latin America Monday 6:00PM-9:00PM Hill 102 Course Number: 21:510:208 Index Number: 15351 Instructor: William Kelly Email: [email protected] Course Description: This course will explore the history of Latin America (defined here as Mexico, South America, the Spanish Caribbean, and Haiti) from the beginning of the independence era in the early 1800s until the present day. We will examine concepts such as violence, race, slavery, religion, poverty, governance, and revolution, and how these social processes have shaped the lives of Latin Americans over the course of the last two and a half centuries. We will explore questions such as: how was colonial Latin American society structured, and how did it change following independence? Why did independence happen early in some places (Haiti, Mexico, Colombia) and late in others (Cuba, Puerto Rico)? How has racial ideology developed in Latin America, and how have Latin Americans historically understood the concept of “race”? Why have Latin Americans structured their governments in particular ways, and how have ideas of governance changed over time? How has the cultural and linguistic diversity in Latin America shaped its history, and how have the experiences of different cultural, linguistic, ethnic, or racial groups differed from one another? We will consult a variety of written and visual forms of media, including books, visual art, published speeches, music, films, and other types of sources in order to explore these and other questions to gain a greater understanding of the historical forces that have shaped Latin American society. Required Text: Cheryl E.