H-France Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uncertainty and Hyperinflation: European Inflation Dynamics After World War I

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF SAN FRANCISCO WORKING PAPER SERIES Uncertainty and Hyperinflation: European Inflation Dynamics after World War I Jose A. Lopez Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Kris James Mitchener Santa Clara University CAGE, CEPR, CES-ifo & NBER June 2018 Working Paper 2018-06 https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/working-papers/2018/06/ Suggested citation: Lopez, Jose A., Kris James Mitchener. 2018. “Uncertainty and Hyperinflation: European Inflation Dynamics after World War I,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Working Paper 2018-06. https://doi.org/10.24148/wp2018-06 The views in this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Uncertainty and Hyperinflation: European Inflation Dynamics after World War I Jose A. Lopez Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Kris James Mitchener Santa Clara University CAGE, CEPR, CES-ifo & NBER* May 9, 2018 ABSTRACT. Fiscal deficits, elevated debt-to-GDP ratios, and high inflation rates suggest hyperinflation could have potentially emerged in many European countries after World War I. We demonstrate that economic policy uncertainty was instrumental in pushing a subset of European countries into hyperinflation shortly after the end of the war. Germany, Austria, Poland, and Hungary (GAPH) suffered from frequent uncertainty shocks – and correspondingly high levels of uncertainty – caused by protracted political negotiations over reparations payments, the apportionment of the Austro-Hungarian debt, and border disputes. In contrast, other European countries exhibited lower levels of measured uncertainty between 1919 and 1925, allowing them more capacity with which to implement credible commitments to their fiscal and monetary policies. -

Southwestern Journal of International Law

\\jciprod01\productn\s\swt\24-1\toc241.txt unknown Seq: 1 9-MAR-18 8:49 SOUTHWESTERN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW VOLUME XXIV 2018 NUMBER 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS SYMPOSIUM FREEDOM OF INFORMATION LAW S O N T H E GLOBAL STAGE: PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE JOHN MOSS AND THE ROOTS OF THE FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ACT: WORLDWIDE IMPLICATIONS .................................... 1 Michael R. Lemov & Nate Jones RALPH NADER, LONE CRUSADER? THE ROLE OF CONSUMER AND PUBLIC INTEREST ADVOCATES IN THE HISTORY OF FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ....................................................... 41 Tom McClean Articles ARGENTINA’S SOLUTION TO THE MICHAEL BROWN TRAVESTY: A ROLE FOR THE COMPLAINANT VICTIM IN CRIMINAL PROCEEDINGS ... 73 Federico S. Efron MARTIAL LAW IN INDIA: THE DEPLOYMENT OF MILITARY UNDER THE ARMED FORCES SPECIAL POWERS ACT, 1958 ................... 117 Khagesh Gautam © 2018 by Southwestern Law School \\jciprod01\productn\s\swt\24-1\toc241.txt unknown Seq: 2 9-MAR-18 8:49 Notes & Comments A CRITIQUE OF PERINCEK ¸ V. SWITZERLAND: INCORPORATING AN INTERNATIONAL AND HISTORICAL CONTEXT IS THE MORE PRUDENT APPROACH TO GENOCIDE DENIAL CASES ........................... 147 Shant N. Nashalian A CUTE COWBOY STOLE OUR MONEY: APPLE, IRELAND, AND WHY THE COURT OF JUSTICE OF THE EUROPEAN UNION SHOULD REVERSE THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION’S DECISION .................. 177 Chantal C. Renta Review BOOK REVIEW PHILIPPE SANDS, EAST WEST STREET: ON THE ORIGINS OF “GENOCIDE” AND “CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY” (ALFRED A. KNOPF ED., 2016) ...................................... 209 Vik Kanwar \\jciprod01\productn\s\swt\24-1\boe241.txt unknown Seq: 3 9-MAR-18 8:49 SOUTHWESTERN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW VOLUME XXIV 2018 NUMBER 1 Editor-in-Chief SHANT N. -

Yesterday's News: Media Framing of Hitler's Early Years, 1923-1924

92 — The Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications, Vol. 6, No. 1 • Spring 2015 Yesterday’s News: Media Framing of Hitler’s Early Years, 1923-1924 Katherine Blunt Journalism and History Elon University Abstract This research used media framing theory to assess newspaper coverage of Hitler published in The New York Times, The Christian Science Monitor, and The Washington Post between 1923 and 1924. An analysis of about 200 articles revealed “credible” and “non-credible” frames relating to his political influence. Prior to Hitler’s trial for treason in 1924, the credible frame was slightly more prevalent. Following his subsequent conviction, the non-credible frame dominated coverage, with reports often presenting Hitler’s failure to over- throw the Bavarian government as evidence of his lack of political skill. This research provides insight into the way American media cover foreign leaders before and after a tipping point—one or more events that call into question their political efficacy. I. Introduction The resentment, suspicion, and chaos that defined global politics during the Great arW continued into the 1920s. Germany plunged into a state of political and economic turmoil following the ratification of the punitive Treaty of Versailles, and the Allies watched with trepidation as it struggled to make reparations pay- ments. The bill — equivalent to 33 billion dollars then and more than 400 billion dollars today — grew increas- ingly daunting as the value of the mark fell from 400 to the dollar in 1922 to 7,000 to the dollar at the start of 1923, when Bavaria witnessed the improbable rise of an Austrian-born artist-turned-politician who channeled German outrage into a nationalistic, anti-Semitic movement that came to be known as the Nazi Party.1 Ameri- can media outlets, intent on documenting the chaotic state of post-war Europe, took notice of Adolf Hitler as he attracted a following and, through their coverage, essentially introduced him to the American public. -

(Swabian Alb) Biosphere Reserve

A Case in Point eco.mont - Volume 5, Number 1, June 2013 ISSN 2073-106X print version 43 ISSN 2073-1558 online version: http://epub.oeaw.ac.at/eco.mont Schwäbische Alb (Swabian Alb) Biosphere Reserve Rüdiger Jooß Abstract Profile On 22 March 2008, the Schwäbische Alb Biosphere Reserve (BR) was founded and Protected area designated by UNESCO in May 2009. It was the 15th BR in Germany and the first of its kind in the Land of Baden-Württemberg. UNESCO BR Schwäbische Alb After a brief preparatory process of just three years, there are now 29 towns and municipalities, three administrative districts, two government regions, as well as Mountain range the federal republic of Germany (Bundesanstalt für Immobilienaufgaben) as owner of the former army training ground in Münsingen involved in the BR, which covers Low mountain range 850 km2 and has a population of ca. 150 000. Country Germany Location The low mountain range of the Swabian Alb be- longs to one of the largest karst areas in Germany. In the northeast it continues in the Franconian Alb and towards the southwest in the Swiss Jura. In Baden- Württemberg the Swabian Alb is a characteristic major landscape. For around 100 km, a steep escarpment of the Swabian Alb, the so-called Albtrauf, rises 300 – 400 metres above the foothills in the north. The Albtrauf links into the plateau of the Swabian Alb, which pre- sents a highly varied, crested relief in the north, while mild undulations dominate in the southern part. The Swabian Alb forms the European watershed between Rhine and Danube. -

Use of 238U-234U Activity Ratio As an Hydrological Tracer: Clues from the Study of Upper Rhine Watersheds F

Geophysical Research Abstracts, Vol. 8, 05694, 2006 SRef-ID: 1607-7962/gra/EGU06-A-05694 © European Geosciences Union 2006 Use of 238U-234U activity ratio as an hydrological tracer: clues from the study of Upper Rhine watersheds F. Chabaux1, M.-C. Pierret1, J. Prunier1, J. Riotte2, B. Ambroise3, Ph. Elsass4 (1) CGS-EOST, University of Strasbourg, France (2) LMTG-IRD, Toulouse, France (3) IMFS, University of Starsbourg, France (4) BRGM, Lingolsheim, France ([email protected], [email protected]) The recognition of the different hydrological compartments controlling the chemi- cal fluxes exported by rivers from watersheds and the determination of their respec- tive contribution, require to define geochimical tracers specific of the chemical fluxes coming from these compartments. Here we show that (234U/238U) activity ratio might become in the future a very helpful tracer to quantify the input of deepwaters into the surface waters. This conclusion relies on the detailed study of U activity ratio variations in surface waters collected on different watersheds of the Upper-Rhine Hydrosystem: (1) study of U activity ratios in spring waters collected in two small experimental watersheds developed on granitic bedrocks, i.e., the Strengbach hydro- geochemical observatory (http://ohge.u-strasbg.fr) and the Ringelbach watershed (2) study of U activity ratios along some Rhine tributaries, flowing on the Vosges Massif (i.e., the Lauter , Sauer and Strengbach streams). All these studies point out that U activity ratios in spring waters of the experimental watersheds as well as in stream waters of Rhine tributaries, can be explained by mixing between surface waters with U activity ratios closed to one, and deeper waters with higher activity ratios. -

202.1017 Fld Riwa River Without

VISION FOR THE FUTURE THE QUALITY OF DRINKING WATER IN EUROPE MORE INFORMATION: How far are we? REQUIRES PREVENTIVE PROTECTION OF THE WATER Cooperation is the key word in the activities RESOURCES: of the Association of River Waterworks The Rhine (RIWA) and the International Association The most important of Waterworks in the Rhine Catchment aim of water pollution (IAWR). control is to enable the Cooperation is necessary to achieve waterworks in the structural, lasting solutions. Rhine river basin to Cooperation forges links between produce quality people and cultures. drinking water at any river time. Strong together without And that is one of the primary merits of this association of waterworks. Respect for the insights and efforts of the RIWA Associations of River other parties in this association is growing Waterworks borders because of the cooperation. This is a good basis for successful The high standards for IAWR International Association activities in coming years. the drinking water of Waterworks in the Rhine quality in Europe catchment area Some common activities of the associations ask for preventive of waterworks: protection of the water • a homgeneous international monitoring resources. Phone: +31 (0) 30 600 90 30 network in the Rhine basin, from the Alps Fax: +31 (0) 30 600 90 39 to the North Sea, • scientific studies on substance and parasites Priority must be given E-mail: [email protected] which are relevant for to protecting water [email protected] drinking water production, resources against publication of monitoring pollutants that can The prevention of Internet: www.riwa.org • results and scientific studie get into the drinking water pollution www.iawr.org in annual reports and other water supply. -

The Rise of the Nazis Revision Guide

Rise of the Nazis Revision Guide Name: Key Topics 1. The Nazis in the 1920s 2. Hitler becomes Chancellor, 1933 3. Hitler becomes Dictator, 1934 @mrthorntonteach Hitler and the early Nazi Party The roots of the Nazi party start in 1889, with the birth of Adolf Hitler but the political beginnings of the party start in 1919 with the set up of the German Workers Party, the DAP. This party was one of the many new parties that set up in the political chaos after the First World War and it was the joining of Adolf Hitler that changed Germanys future forever. The early life of Hitler Hitler wanted to In 1913, he moved to Hitler was shocked by become an artists but Munich and became Germanys defeat in WWI was rejected by the obsessed with all things and blamed the Weimar Vienna Art School German Republic Hitler was born Between 1908- He fought in the First In 1919, Hitler begins to spy in Austria in 13, he was World War, winning the on the German Workers 1889 to an homeless and Iron Cross but was Party (DAP) but then joins abusive father. sold paintings wounded by gas in 1918 the party, soon taking over. Who were the DAP? The DAP were national socialists: The German Workers Party Nationalists – believed that all policies should should (DAP) was set up by Anton be organised to make the nation stronger Drexler in 1919 in Munich. Socialists – believed that the country's land, industry At first there were only a small and wealth should below to the workers. -

Themenliste GN Isenach-Eckbach

Themenliste GN Isenach-Eckbach GN Jahr Ort Schwerpunktthema Referat 1 Referat 2 Referat 3 Referat 4 Referat 5 Exkursion 2019 Das neue Naturnahe Bäche in Ortslagen sowie Die Renaturierung des Der neue Landesnaturschutzgesetz Neurungen zum Ökologische Mindestanforderungen Besichtigung der GN Rehbach/Speyerbach, GN Neustadt an der Speyerbachs im „Grünzug Böbig“ Gewässerentwicklungsplan für Rheinland-Pfalz (LNatSchG) – 2018 Landesnaturschutzgesetz an die Gewässerentwicklung und Speyerbachrenaturierung in Stadtgebiet Isenach/Eckbach Weinstraße in Neustadt/W. – Planung und den Rehbach in der Germarkung Auswirkungen auf die (LNatSchG RLP) und Auswirkungen –unterhaltung in Ortslagen von Neustadt/Weinstraße Umsetzung Neustadt und Haßloch Wasserwirtschaft und erste auf die Wasserwirtschaft Erfahrungen Vorstellung des "alla hopp"- Gewässerentwicklung in der Verwendung von Besichtigung der Alla hopp Anlage am Gewässerentwicklung am rojektes am Triefenbach in Gebeitsfremde Pflanzen GN Rehbach/Speyerbach, GN Verbandsgemeinde Edenkoben – gebietseigenem Wildsaatgut – Triefenbach und andere Maßnahmen im 2017 Edenkoben Triefenbach, Edenkoben - Planungsprämissen (Neophyten) an Fliegwässern – Isenach/Eckbach Erfahrungen, Planungen und Chancen für den Gebiet der Verbandsgemeinde Wildsaatgut und Neophyten und Erfahrungen bei der Planung Wie gehen wir damit um? Perspektiven Grünlandartenschutz Edenkoben und Umsetzung Vorstellung des NABU- Projektes: Wiederbelebung Die lineare Durchgängigkeit des Herstellung der linearen Herstellung der Durchgängigkeit ehemaliger -

Council CNL(14)23 Annual Progress Report on Actions Taken

Agenda Item 6.1 For Information Council CNL(14)23 Annual Progress Report on Actions Taken Under Implementation Plans for the Calendar Year 2013 EU – Germany CNL(14)23 Annual Progress Report on Actions taken under Implementation Plans for the Calendar Year 2013 The primary purposes of the Annual Progress Reports are to provide details of: • any changes to the management regime for salmon and consequent changes to the Implementation Plan; • actions that have been taken under the Implementation Plan in the previous year; • significant changes to the status of stocks, and a report on catches; and • actions taken in accordance with the provisions of the Convention These reports will be reviewed by the Council. Please complete this form and return it to the Secretariat by 1 April 2014. The annual report 2013 is structured according to the catchments of the rivers Rhine, Ems, Weser and Elbe. Party: European Union Jurisdiction/Region: Germany 1: Changes to the Implementation Plan 1.1 Describe any proposed revisions to the Implementation Plan and, where appropriate, provide a revised plan. Item 3.3 - Provide an update on progress against actions relating to Aquaculture, Introductions and Transfers and Transgenics (section 4.8 of the Implementation Plan) - has been supplemented by a new measure (A2). 1.2 Describe any major new initiatives or achievements for salmon conservation and management that you wish to highlight. Rhine ICPR The 15th Conference of Rhine Ministers held on 28th October 2013 in Basel has agreed on the following points for the rebuilding of a self-sustainable salmon population in the Rhine system in its Communiqué of Ministers (www.iksr.org / International Cooperation / Conferences of Ministers): - Salmon stocking can be reduced step by step in parts of the River Sieg system in the lower reaches of the Rhine, even though such stocking measures on the long run remain absolutely essential in the upper reaches of the Rhine, in order to increase the number of returnees and to enhance the carefully starting natural reproduction. -

Proof of Reproduction of Salmon Returned to the Rhine System

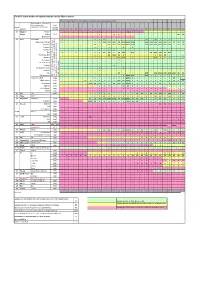

Proof of reproduction of salmon returned to the Rhine system Year of spawning proof (reproduction during the preceding autumn/winter) Project water - Selection of the most important First Countr tributaries (* no stocking) salmon y System stocking 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 D Wupper- Wupper / / / / / / / / 0 / / / / / (X) / / / / / / / / / / X Dhünn Dhünn 1993 / / / / / / / / 0 / / X X / / / / / / / / / / / XX XX Eifgenbach / / / / / / / / / / / / 0 / / / / / / / / / / / / / D Sieg Sieg NRW X / / / / / / X 0 XX / / / / / / / / XX / XX 0 0 0 / / / Agger (lower 30 km) X / / / / / / 0 0 XXX XXX XXX XX XXXX XXXX XXXX / / XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XX XX XX XX Naafbach / / / / / / / XX 0 / XXX XXX XXX XXXX XXXX XXXX / / XXX XXX XXX XXXX XXX XXX 0 XX XX Pleisbach / / / / / / / 0 / / 0 / / X / X / / / / / / / / / / Hanfbach / / / / / / / / 0 / 0 X / / / / / / / / / / / / / / Bröl X / / X / / / 0 0 XX XX 0 XX XXX / XXX / / / XX XXX XXX XX XXX / / Homburger Bröl / / / / / / / 0 0 / XX XXX XX X / / / / / / 0 XX XX 0 / / 0 Waldbröl / / / / / / / 0 0 / 0 0 XXX XXX / 0 / / / / XXX 0 0 0 / / 0 Derenbach / / / / / / / / / / / / 0 / / / / / / / / / / / / / Steinchesbach / / / / / / / / / / / / 0 / / / / / / / / / / / / / Krabach / / / / / / / / / / / X / / / / / / / / / / / / / / Gierzhagener Bach / / / / / / / / 0 / / / / X / / / / / / / / / / / / Irsenbach / / / / / / / / 0 / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / Sülz / / / / / / / 0 0 / / / XX / / / / / -

Rare Earth Elements As Emerging Contaminants in the Rhine River, Germany and Its Tributaries

Rare earth elements as emerging contaminants in the Rhine River, Germany and its tributaries by Serkan Kulaksız A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geochemistry Approved, Thesis Committee _____________________________________ Prof. Dr. Michael Bau, Chair Jacobs University Bremen _____________________________________ Prof. Dr. Andrea Koschinsky Jacobs University Bremen _____________________________________ Dr. Dieter Garbe-Schönberg Universität Kiel Date of Defense: June 7th, 2012 _____________________________________ School of Engineering and Science TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I – INTRODUCTION 1 1. Outline 1 2. Research Goals 4 3. Geochemistry of the Rare Earth Elements 6 3.1 Controls on Rare Earth Elements in River Waters 6 3.2 Rare Earth Elements in Estuaries and Seawater 8 3.3 Anthropogenic Gadolinium 9 3.3.1 Controls on Anthropogenic Gadolinium 10 4. Demand for Rare Earth Elements 12 5 Rare Earth Element Toxicity 16 6. Study Area 17 7. References 19 Acknowledgements 28 CHAPTER II – SAMPLING AND METHODS 31 1. Sample Preparation 31 1.1 Pre‐concentration 32 2. Methods 34 2.1 HCO3 titration 34 2.2 Ion Chromatography 34 2.3 Inductively Coupled Plasma – Optical Emission Spectrometer 35 2.4 Inductively Coupled Plasma – Mass Spectrometer 35 2.4.1 Method reliability 36 3. References 41 CHAPTER III – RARE EARTH ELEMENTS IN THE RHINE RIVER, GERMANY: FIRST CASE OF ANTHROPOGENIC LANTHANUM AS A DISSOLVED MICROCONTAMINANT IN THE HYDROSPHERE 43 Abstract 44 1. Introduction 44 2. Sampling sites and Methods 46 2.1 Samples 46 2.2 Methods 46 2.3 Quantification of REE anomalies 47 3. Results and Discussion 48 4. -

Weimar and Nazi Germany P1 KO

Weimar and Nazi Germany, 1819-1939 PART ONE: The Weimar Republic 1918-29 The origins of the Republic 1918 – 19 Early challenges to the Republic, 1919 - 23 Left Wing Right Wing ● The German Kaiser aBdicated Treaty of Versailles: Opposed Capitalism, Supported Land: Germany lost 10% of it’s population, 50% iron and 15% coal due to the failure of WW1. wanted Germany to Capitalism, wanted a resources. ● Friedrich EBert Became the first Army: Cut to 100,000 men, no air force, small navy be controlled by the strong government, chancellor of the new repuBlic. Money: 6.6 Billion marks had to Be paid to the allies. people. army and Kaiser. Strengths of Weimar Constitution: Blame: Germany had to take the Blame for causing the war. • Germany Became more French Occupation of the Ruhr 1923: democratic. Stab in the Back: Some German people think that the army was • Germany had no money and count not pay • Germans had the right to elect their betrayed by German politicians as they signed the Treaty of the reparations. leaders Versailles. • This made France angry so they invaded • Women could vote for the first time the Ruhr and took control of 80% of • All Germans over 21 could vote November Criminals: German people who were angry with the Germany’s coal, iron and steel. • Checks and Balances prevented any leaders of the new repuBlic who surrendered in NovemBer 1918. • In protest, German workers went on strike. one person having too much power. This is known as passive resistance. Spartacist Revolt 1919: Left wing uprising, supported By communists.