Rhumb Lines and Map Wars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mollweide Projection and the ICA Logo Cartotalk, October 21, 2011 Institute of Geoinformation and Cartography, Research Group Cartography (Draft Paper)

Mollweide Projection and the ICA Logo CartoTalk, October 21, 2011 Institute of Geoinformation and Cartography, Research Group Cartography (Draft paper) Miljenko Lapaine University of Zagreb, Faculty of Geodesy, [email protected] Abstract The paper starts with the description of Mollweide's life and work. The formula or equation in mathematics known after him as Mollweide's formula is shown, as well as its proof "without words". Then, the Mollweide map projection is defined and formulas derived in different ways to show several possibilities that lead to the same result. A generalization of Mollweide projection is derived enabling to obtain a pseudocylindrical equal-area projection having the overall shape of an ellipse with any prescribed ratio of its semiaxes. The inverse equations of Mollweide projection has been derived, as well. The most important part in research of any map projection is distortion distribution. That means that the paper continues with the formulas and images enabling us to get some filling about the liner and angular distortion of the Mollweide projection. Finally, the ICA logo is used as an example of nice application of the Mollweide projection. A small warning is put on the map painted on the ICA flag. It seams that the map is not produced according to the Mollweide projection and is different from the ICA logo map. Keywords: Mollweide, Mollweide's formula, Mollweide map projection, ICA logo 1. Introduction Pseudocylindrical map projections have in common straight parallel lines of latitude and curved meridians. Until the 19th century the only pseudocylindrical projection with important properties was the sinusoidal or Sanson-Flamsteed. -

Map Projections--A Working Manual

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com 7 I- , t 7 < ?1 > I Map Projections — A Working Manual By JOHN P. SNYDER U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1395 _ i UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFIGE, WASHINGTON: 1987 no U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Gordon P. Eaton, Director First printing 1987 Second printing 1989 Third printing 1994 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Snyder, John Parr, 1926— Map projections — a working manual. (U.S. Geological Survey professional paper ; 1395) Bibliography: p. Supt. of Docs. No.: I 19.16:1395 1. Map-projection — Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. Title. II. Series: Geological Survey professional paper : 1395. GA110.S577 1987 526.8 87-600250 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, DC 20402 PREFACE This publication is a major revision of USGS Bulletin 1532, which is titled Map Projections Used by the U.S. Geological Survey. Although several portions are essentially unchanged except for corrections and clarification, there is consider able revision in the early general discussion, and the scope of the book, originally limited to map projections used by the U.S. Geological Survey, now extends to include several other popular or useful projections. These and dozens of other projections are described with less detail in the forthcoming USGS publication An Album of Map Projections. As before, this study of map projections is intended to be useful to both the reader interested in the philosophy or history of the projections and the reader desiring the mathematics. -

An Efficient Technique for Creating a Continuum of Equal-Area Map Projections

Cartography and Geographic Information Science ISSN: 1523-0406 (Print) 1545-0465 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tcag20 An efficient technique for creating a continuum of equal-area map projections Daniel “daan” Strebe To cite this article: Daniel “daan” Strebe (2017): An efficient technique for creating a continuum of equal-area map projections, Cartography and Geographic Information Science, DOI: 10.1080/15230406.2017.1405285 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/15230406.2017.1405285 View supplementary material Published online: 05 Dec 2017. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tcag20 Download by: [4.14.242.133] Date: 05 December 2017, At: 13:13 CARTOGRAPHY AND GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION SCIENCE, 2017 https://doi.org/10.1080/15230406.2017.1405285 ARTICLE An efficient technique for creating a continuum of equal-area map projections Daniel “daan” Strebe Mapthematics LLC, Seattle, WA, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Equivalence (the equal-area property of a map projection) is important to some categories of Received 4 July 2017 maps. However, unlike for conformal projections, completely general techniques have not been Accepted 11 November developed for creating new, computationally reasonable equal-area projections. The literature 2017 describes many specific equal-area projections and a few equal-area projections that are more or KEYWORDS less configurable, but flexibility is still sparse. This work develops a tractable technique for Map projection; dynamic generating a continuum of equal-area projections between two chosen equal-area projections. -

![Rcosmo: R Package for Analysis of Spherical, Healpix and Cosmological Data Arxiv:1907.05648V1 [Stat.CO] 12 Jul 2019](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0993/rcosmo-r-package-for-analysis-of-spherical-healpix-and-cosmological-data-arxiv-1907-05648v1-stat-co-12-jul-2019-240993.webp)

Rcosmo: R Package for Analysis of Spherical, Healpix and Cosmological Data Arxiv:1907.05648V1 [Stat.CO] 12 Jul 2019

CONTRIBUTED RESEARCH ARTICLE 1 rcosmo: R Package for Analysis of Spherical, HEALPix and Cosmological Data Daniel Fryer, Ming Li, Andriy Olenko Abstract The analysis of spatial observations on a sphere is important in areas such as geosciences, physics and embryo research, just to name a few. The purpose of the package rcosmo is to conduct efficient information processing, visualisation, manipulation and spatial statistical analysis of Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) radiation and other spherical data. The package was developed for spherical data stored in the Hierarchical Equal Area isoLatitude Pixelation (Healpix) representation. rcosmo has more than 100 different functions. Most of them initially were developed for CMB, but also can be used for other spherical data as rcosmo contains tools for transforming spherical data in cartesian and geographic coordinates into the HEALPix representation. We give a general description of the package and illustrate some important functionalities and benchmarks. Introduction Directional statistics deals with data observed at a set of spatial directions, which are usually positioned on the surface of the unit sphere or star-shaped random particles. Spherical methods are important research tools in geospatial, biological, palaeomagnetic and astrostatistical analysis, just to name a few. The books (Fisher et al., 1987; Mardia and Jupp, 2009) provide comprehensive overviews of classical practical spherical statistical methods. Various stochastic and statistical inference modelling issues are covered in (Yadrenko, 1983; Marinucci and Peccati, 2011). The CRAN Task View Spatial shows several packages for Earth-referenced data mapping and analysis. All currently available R packages for spherical data can be classified in three broad groups. The first group provides various functions for working with geographic and spherical coordinate systems and their visualizations. -

![Arxiv:1811.01571V2 [Cs.CV] 24 Jan 2019 Many Traditional Cnns on 3D Data Simply Extend the 2D Convolutional Op- Erations to 3D, for Example, the Work of Wu Et Al](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4678/arxiv-1811-01571v2-cs-cv-24-jan-2019-many-traditional-cnns-on-3d-data-simply-extend-the-2d-convolutional-op-erations-to-3d-for-example-the-work-of-wu-et-al-314678.webp)

Arxiv:1811.01571V2 [Cs.CV] 24 Jan 2019 Many Traditional Cnns on 3D Data Simply Extend the 2D Convolutional Op- Erations to 3D, for Example, the Work of Wu Et Al

SPNet: Deep 3D Object Classification and Retrieval using Stereographic Projection Mohsen Yavartanoo1[0000−0002−0109−1202], Eu Young Kim1[0000−0003−0528−6557], and Kyoung Mu Lee1[0000−0001−7210−1036] Department of ECE, ASRI, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea https://cv.snu.ac.kr/ fmyavartanoo, shreka116, [email protected] Abstract. We propose an efficient Stereographic Projection Neural Net- work (SPNet) for learning representations of 3D objects. We first trans- form a 3D input volume into a 2D planar image using stereographic projection. We then present a shallow 2D convolutional neural network (CNN) to estimate the object category followed by view ensemble, which combines the responses from multiple views of the object to further en- hance the predictions. Specifically, the proposed approach consists of four stages: (1) Stereographic projection of a 3D object, (2) view-specific fea- ture learning, (3) view selection and (4) view ensemble. The proposed ap- proach performs comparably to the state-of-the-art methods while having substantially lower GPU memory as well as network parameters. Despite its lightness, the experiments on 3D object classification and shape re- trievals demonstrate the high performance of the proposed method. Keywords: 3D object classification · 3D object retrieval · Stereographic Projection · Convolutional Neural Network · View Ensemble · View Se- lection. 1 Introduction In recent years, success of deep learning methods, in particular, convolutional neural network (CNN), has urged rapid development in various computer vision applications such as image classification, object detection, and super-resolution. Along with the drastic advances in 2D computer vision, understanding 3D shapes and environment have also attracted great attention. -

Visio-MERCATOR ENG2.Vsd

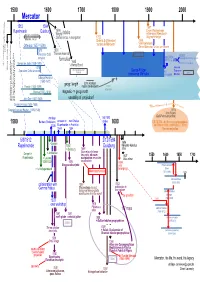

1500 1600 1700 1800 1900 2000 Mercator 1512 1594 1897 Rupelmonde Duisburg 1599 tables Lt-gen Wauwermans Italian composite Wright tables article about Mercator in Certain erros in navigation 1752 Biographie belge atlases IATO 1869 middle 15th Century Diderot & d’Alembert “cartes de Mercator” Van Raemdonck Ortelius (1527-1598) Gérard Mercator, sa vie, son oeuvre printing 1570 1600 Theatrum Orbis Thomas Harrriot projection MGRS terrarum 1772 1825 1914 post WWI military grid reference system formulas Johan Lambert Carl Friedrich Gauss Johann Krüger NATO UTM Gerard de Jode (1509-1591) 1645 transverse Mercator transverse Mercator transverse Mercator civil reference system fall of Constantinople Henry Bond 1578 (sphere) (ellipsoid) (ellipsoid) Universal 1492 end of Reconquista Mercatorprojection Transverse Speculum Orbis terrarum formula Gauss-Krüger 1942 grid transverse Mercator developped Mercator Judocus Hondius (1563-1612) + geogr. length John Harrison Plantijn (1520-1589) marine timekeepers use of projection Moretus (1543-1610) magnetic <> geogr north John Dee (1527-1608) useability of projection? 1488 Bartholomeus Dias rounded Cape of Good Hope 1492 Columbus ‘America’ discovered 1498 Vasco da Gama reached India via Africa 1519 – 1522 Magellan around the world Gemma Frisius (1508-1555) 1904 criticism + -- Gaspard van der Heyden (1496-1549) 1974 Arne Peters (Gall-Peters-projection) mariage 5/5/1590 1500 Barbara Shellekens arrested in met Ortelius stroke 1600 CRITICISM - but from non-cartographers - 1536 Rupelmonde in Frankfurt on ethnocentrism, -

A Unified Plane Coordinate Reference System

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received COLVOCORESSES, Alden Partridge, 1918- A UNIFIED PLANE COORDINATE REFERENCE SYSTEM. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1965 Geography University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan A UNIFIED PLANE COORDINATE REFERENCE SYSTEM DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University Alden P. Colvocoresses, B.S., M.Sc. Lieutenant Colonel, Corps of Engineers United States Army * * * * * The Ohio State University 1965 Approved by Adviser Department of Geodetic Science PREFACE This dissertation was prepared while the author was pursuing graduate studies at The Ohio State University. Although attending school under order of the United States Army, the views and opinions expressed herein represent solely those of the writer. A list of individuals and agencies contributing to this paper is presented as Appendix B. The author is particularly indebted to two organizations, The Ohio State University and the Army Map Service. Without the combined facilities of these two organizations the preparation of this paper could not have been accomplished. Dr. Ivan Mueller of the Geodetic Science Department of The Ohio State University served as adviser and provided essential guidance and counsel. ii VITA September 23, 1918 Born - Humboldt, Arizona 1941 oo.oo.o BoS. in Mining Engineering, University of Arizona 1941-1945 .... Military Service, European Theatre 1946-1950 o . o Mining Engineer, Magma Copper -

Uon Digital Repository Home

University of Nairobi School of Engineering Building a QGIS Helper Application to Overcome the Challenges of Cassini to UTM Coordinate System Conversions in Kenya BY Ajanga Dissent Ingati F56/81982/2015 A Project submitted in partial fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Science in Geographical Information Systems, in the Department of Geospatial & Space Technology of the University of Nairobi October 2017 I Declaration I, Ajanga Dissent Ingati, hereby declare that this project is my original work. To the best of my knowledge, the work presented here has not been presented for a degree in any other Institution of Higher Learning. ……………………………………. ……………………… .……..……… Name of student Signature Date This project has been submitted for examination with my approval as university supervisor. ……………………………………. ……………………… .……..……… Name of Supervisor Signature Date I Dedication I dedicate this work to my family for their support throughout the entire process of pursuing this degree and to the completion of the project. Your encouragement has been instrumental in ensuring the success of this project; may God truly bless you. II Acknowledgement I would like to show my heartfelt appreciation to all the people who saw me through the process of preparing this report. These thanks go to all those who provided technical support, talked through the issues I studied, read, wrote, gave comments, and also those who assisted in editing and proof reading of this project report before submission. I would like to thank Steve Firsake for his technical support through Python Programing. Special thanks also go to Dr.-Ing. Musyoka for his technical advice and support for the entire project. -

Bucky Fuller & Spaceship Earth

Ivorypress Art + Books presents BUCKY FULLER & SPACESHIP EARTH © RIBA Library Photographs Collection BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD BUCKMINSTER FULLER Born in 1895 into a distinguished family of Massachusetts, which included his great aunt Margaret Fuller, a feminist and writer linked with the transcendentalist circles of Emerson and Thoreau, Richard Buckminster Fuller Jr left Harvard University, where all the Fuller men had studied since 1740, to become an autodidact and get by doing odd jobs. After marrying Anne Hewlett and serving in the Navy during World War I, he worked for his architect father-in-law at a company that manufactured reinforced bricks. The company went under in 1927, and Fuller set out on a year of isolation and solitude, during which time he nurtured many of his ideas—such as four-dimensional thinking (including time), which he dubbed ‘4D’—and the search for maximum human benefit with minimum use of energy and materials using design. He also pondered inventing light, portable towers that could be moved with airships anywhere on the planet, which he was already beginning to refer to as ‘Spaceship Earth’. Dymaxion Universe Prefabrication and the pursuit of lightness through cables were the main characteristics of 4D towers, just like the module of which they were made, a dwelling supported by a central mast whose model was presented as a single- family house and was displayed in 1929 at the Marshall Field’s department store in Chicago and called ‘Dymaxion House’. The name was coined by the store’s public relations team by joining the words that most often appeared in Fuller’s eloquent explanations: dynamics, maximum, and tension, and which the visionary designer would later use for other inventions like the car, also called Dymaxion. -

Early & Rare World Maps, Atlases & Rare Books

19219a_cover.qxp:Layout 1 5/10/11 12:48 AM Page 1 EARLY & RARE WORLD MAPS, ATLASES & RARE BOOKS Mainly from a Private Collection MARTAYAN LAN CATALOGUE 70 EAST 55TH STREET • NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10022 45 To Order or Inquire: Telephone: 800-423-3741 or 212-308-0018 Fax: 212-308-0074 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.martayanlan.com Gallery Hours: Monday through Friday 9:30 to 5:30 Saturday and Evening Hours by Appointment. We welcome any questions you might have regarding items in the catalogue. Please let us know of specific items you are seeking. We are also happy to discuss with you any aspect of map collecting. Robert Augustyn Richard Lan Seyla Martayan James Roy Terms of Sale: All items are sent subject to approval and can be returned for any reason within a week of receipt. All items are original engrav- ings, woodcuts or manuscripts and guaranteed as described. New York State residents add 8.875 % sales tax. Personal checks, Visa, MasterCard, American Express, and wire transfers are accepted. To receive periodic updates of recent acquisitions, please contact us or register on our website. Catalogue 45 Important World Maps, Atlases & Geographic Books Mainly from a Private Collection the heron tower 70 east 55th street new york, new york 10022 Contents Item 1. Isidore of Seville, 1472 p. 4 Item 2. C. Ptolemy, 1478 p. 7 Item 3. Pomponius Mela, 1482 p. 9 Item 4. Mer des hystoires, 1491 p. 11 Item 5. H. Schedel, 1493, Nuremberg Chronicle p. 14 Item 6. Bergomensis, 1502, Supplementum Chronicum p. -

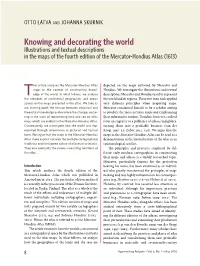

Knowing and Decorating the World Illustrations and Textual Descriptions in the Maps of the Fourth Edition of the Mercator-Hondius Atlas (1613)

OTTO LATVA AND JOHANNA SKURNIK Knowing and decorating the world Illustrations and textual descriptions in the maps of the fourth edition of the Mercator-Hondius Atlas (1613) his article analyses the Mercator-Hondius Atlas depicted on the maps authored by Mercator and maps in the context of constructing knowl- Hondius. We investigate the illustrations and textual Tedge of the world. In what follows, we analyse descriptions Mercator and Hondius used to represent the elem ents of continental geographies and ocean the world and its regions. These two men each applied spaces on the maps presented in the atlas. We take as very different principles when preparing maps: our starting point the tension between empirical and Mercator considered himself to be a scholar aiming theoretical knowledge and examine the changes occur- to produce the most accurate maps and emphasizing ring in the ways of representing land and sea on atlas their informative content. Hondius, however, evolved maps which are evident in the Mercator-Hondius Atlas. from an engraver to a publisher of atlases and globes, Consequently, we investigate how the world was rep- turning them into a profitable business (van der resented through information in pictorial and textual Krogt 1997: 35; Zuber 2011: 516). We argue that the form. We argue that the maps in the Mercator-Hondius maps in the Mercator-Hondius Atlas can be read as a Atlas make explicit not only the multiple cartographical demonstration of the layered nature of the atlas as an trad itions and the layered nature of atlases as artefacts. epistemological artefact. They also exemplify the various coexisting functions of The principles and practices employed by dif- the atlas. -

Brochure Exhibition Texts

BROCHURE EXHIBITION TEXTS “TO CHANGE SOMETHING, BUILD A NEW MODEL THAT MAKES THE EXISTING MODEL OBSOLETE” Radical Curiosity. In the Orbit of Buckminster Fuller September 16, 2020 - March 14, 2021 COVER Buckminster Fuller in his class at Black Mountain College, summer of 1948. Courtesy The Estate of Hazel Larsen Archer / Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center. RADICAL CURIOSITY. IN THE ORBIT OF BUCKMINSTER FULLER IN THE ORBIT OF BUCKMINSTER RADICAL CURIOSITY. Hazel Larsen Archer. “Radical Curiosity. In the Orbit of Buckminster Fuller” is a journey through the universe of an unclassifiable investigator and visionary who, throughout the 20th century, foresaw the major crises of the 21st century. Creator of a fascinating body of work, which crossed fields such as architecture, engineering, metaphysics, mathematics and education, Richard Buckminster Fuller (Milton, 1895 - Los Angeles, 1983) plotted a new approach to combine design and science with the revolutionary potential to change the world. Buckminster Fuller with the Dymaxion Car and the Fly´s Eye Dome, at his 85th birthday in Aspen, 1980 © Roger White Stoller The exhibition peeps into Fuller’s kaleidoscope from the global state of emergency of year 2020, a time of upheaval and uncertainty that sees us subject to multiple systemic crises – inequality, massive urbanisation, extreme geopolitical tension, ecological crisis – in which Fuller worked tirelessly. By presenting this exhibition in the midst of a pandemic, the collective perspective on the context is consequently sharpened and we can therefore approach Fuller’s ideas from the core of a collapsing system with the conviction that it must be transformed. In order to break down the barriers between the different fields of knowledge and creation, Buckminster Fuller defined himself as a “Comprehensive Anticipatory Design Scientist,” a scientific designer (and vice versa) able to formulate solutions based on his comprehensive knowledge of universe.