China, People's Republic of | Grove Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yuan Muzhi Y La Comedia Modernista De Shanghai

Yuan Muzhi y la comedia modernista de Shanghai Ricard Planas Penadés ------------------------------------------------------------------ TESIS DOCTORAL UPF / Año 2019 Director de tesis Dr. Manel Ollé Rodríguez Departamento de Humanidades Als meus pares, en Francesc i la Fina. A la meva companya, Zhang Yajing. Per la seva ajuda i comprensió. AGRADECIMIENTOS Quisiera dar mis agradecimientos al Dr. Manel Ollé. Su apoyo en todo momento ha sido crucial para llevar a cabo esta tesis doctoral. Del mismo modo, a mis padres, Francesc y Fina y a mi esposa, Zhang Yajing, por su comprensión y logística. Ellos han hecho que los días tuvieran más de veinticuatro horas. Igualmente, a mi hermano Roger, que ha solventado más de una duda técnica en clave informática. Y como no, a mi hijo, Eric, que ha sido un gran obstáculo a la hora de redactar este trabajo, pero también la mayor motivación. Un especial reconocimiento a Zheng Liuyi, mi contacto en Beijing. Fue mi ángel de la guarda cuando viví en aquella ciudad y siempre que charlamos me ofrece una versión interesante sobre la actualidad académica china. Por otro lado, agradecer al grupo de los “Aspasians” aquellos descansos entra página y página, aquellos menús que hicieron más llevadero el trabajo solitario de investigación y redacción: Xavier Ortells, Roberto Figliulo, Manuel Pavón, Rafa Caro y Sergio Sánchez. v RESUMEN En esta tesis se analizará la obra de Yuan Muzhi, especialmente los filmes que dirigió, su debut, Scenes of City Life (都市風光,1935) y su segunda y última obra Street Angel ( 马路天使, 1937). Para ello se propone el concepto comedia modernista de Shanghai, como una perspectiva alternativa a las que se han mantenido tanto en la academia china como en la anglosajona. -

Kūnqǔ in Practice: a Case Study

KŪNQǓ IN PRACTICE: A CASE STUDY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THEATRE OCTOBER 2019 By Ju-Hua Wei Dissertation Committee: Elizabeth A. Wichmann-Walczak, Chairperson Lurana Donnels O’Malley Kirstin A. Pauka Cathryn H. Clayton Shana J. Brown Keywords: kunqu, kunju, opera, performance, text, music, creation, practice, Wei Liangfu © 2019, Ju-Hua Wei ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my gratitude to the individuals who helped me in completion of my dissertation and on my journey of exploring the world of theatre and music: Shén Fúqìng 沈福庆 (1933-2013), for being a thoughtful teacher and a father figure. He taught me the spirit of jīngjù and demonstrated the ultimate fine art of jīngjù music and singing. He was an inspiration to all of us who learned from him. And to his spouse, Zhāng Qìnglán 张庆兰, for her motherly love during my jīngjù research in Nánjīng 南京. Sūn Jiàn’ān 孙建安, for being a great mentor to me, bringing me along on all occasions, introducing me to the production team which initiated the project for my dissertation, attending the kūnqǔ performances in which he was involved, meeting his kūnqǔ expert friends, listening to his music lessons, and more; anything which he thought might benefit my understanding of all aspects of kūnqǔ. I am grateful for all his support and his profound knowledge of kūnqǔ music composition. Wichmann-Walczak, Elizabeth, for her years of endeavor producing jīngjù productions in the US. -

Mr Chen Jiulin's Speech for Global Entropolis Singapore

Mr Chen Jiulin's Speech for Global Entropolis Singapore 29/10/03 Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. It is a great honor and privilege for me to address this distinguished gathering. I would like to thank the Economic Development Board of Singapore for giving me the opportunity to share my thoughts with you today. I have been invited to discuss the recent deregulations in China and the opportunities they present. First of all, please allow me to give a few statistics to show the results of these efforts: - Chinese GDP grew at an annual average rate of 9.4% between 1978 and 2002. Third-quarter 2003 GDP growth was 9.1% year-on-year, and full-year estimates are for at least 8.5% growth. - Exports grew at a 22% rate in 2002 and are estimated by the Asian Development Bank to rise 25% in 2003. Imports, meanwhile, were up 21% in 2002, and ADB forecasts as much as 36% growth in 2003. - Foreign direct investment reached US$52.7 billion in 2002 and is expected to reach US$60 billion in 2003. There have been many efforts at reform and deregulation in China, corresponding with its reform and open-door policies. For example, since China entered into WTO, China has lowered import duties on over 5,000 goods and allowed the average tariff to drop from 15.3% to 12%. China's legal system is also undergoing rapid change, with some 2,300 legal documents having been reviewed since reform started, including 830 cancelled outright and 325 revised. Among the biggest deregulations are those in financial services, telecommunications, utilities, state-owned enterprises and civil aviation. -

The Chinese Phonetic Transcriptions of Old Turkish Words in the Chinese Sources from 6Th -9Th Century Focused on the Original Word Transcribed As Tujue 突厥*

The Chinese Phonetic Transcriptions of Old Title Turkish Words in the Chinese Sources from 6th - 9th Century : Focused on the Original Word Transcribed as Tujue 突厥 Author(s) Kasai, Yukiyo Citation 内陸アジア言語の研究. 29 P.57-P.135 Issue Date 2014-08-17 Text Version publisher URL http://hdl.handle.net/11094/69762 DOI rights Note Osaka University Knowledge Archive : OUKA https://ir.library.osaka-u.ac.jp/ Osaka University 57 The Chinese Phonetic Transcriptions of Old Turkish Words in the Chinese Sources from 6th -9th Century Focused on the Original Word Transcribed as Tujue 突厥* Yukiyo KASAI 0. Introduction The Turkish tribes which originated from Mongolia contacted since time immemorial with their various neighbours. Amongst those neighbours China, one of the most influential countries in East Asia, took note of their activities for reasons of its national security on the border areas to the North of its territory. Especially after an political unit of Turkish tribes called Tujue 突厥 had emerged in the middle of the 6th c. as the first Turkish Kaganate in Mongolia and become threateningly powerful, the Chinese dynasties at that time followed the Turks’ every move with great interest. The first Turkish Kaganate broke down in the first half of the 7th c. and came under the rule of the Chinese Tang 唐–dynasty, but * I would like first to express my sincere thanks to Prof. Dr. DESMOND DURKIN-MEISTERERNST who gave me useful advice about the contents of this article and corrected my English, too. My gratitude also goes to Prof. TAKAO MORIYASU and Prof. -

Dancing with China: (In a Psyche of Adaptability, Adjustment, and Cooperation)

Comparative Connections A Quarterly E-Journal on East Asian Bilateral Relations China-Southeast Asia Relations: Dancing with China: (In a Psyche of Adaptability, Adjustment, And Cooperation) Ronald N. Montaperto East Carolina University Syntax and usage aside, the language of the subtitle of this analysis (paraphrased from an article in People’s Daily) captures fully the thrust and character of Beijing’s relations with Southeast Asia during the second quarter of 2005. Buoyed by a swift international response, a high level of assistance, and the success of their own hard work, the nations of Southeast Asia threw off the torpor induced by the tsunami of December 2004 and returned to business as usual. Beijing seized the opportunity and immediately reenergized plans placed in temporary, forced abeyance in the wake of the disaster. The result was yet another series of apparent Chinese successes in Beijing’s continuing drive to gain acceptance as a good neighbor and further enhance its regional status. The good neighbor I: the travels of Hu Jintao During the quarter, China’s highest leadership made its presence felt in five of the six longest-standing members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Australia and New Zealand, both of which seek a larger measure of economic interaction with Southeast Asia, also received attention. On April 20, President Hu Jintao began an eight-day journey that took him to Indonesia, Brunei, and the Philippines. Later, on May 19 National Peoples’ Congress (NPC) Chair Wu Bangguo began a four-nation tour that included Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, and Malaysia. Regional media outlets gave both missions high marks. -

Voyager's Gold Record

Voyager's Gold Record https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voyager_Golden_Record #14 score, next page. YouTube (Perlman): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aVzIfSsskM0 Each Voyager space probe carries a gold-plated audio-visual disc in the event that the spacecraft is ever found by intelligent life forms from other planetary systems.[83] The disc carries photos of the Earth and its lifeforms, a range of scientific information, spoken greetings from people such as the Secretary- General of the United Nations and the President of the United States and a medley, "Sounds of Earth," that includes the sounds of whales, a baby crying, waves breaking on a shore, and a collection of music, including works by Mozart, Blind Willie Johnson, Chuck Berry, and Valya Balkanska. Other Eastern and Western classics are included, as well as various performances of indigenous music from around the world. The record also contains greetings in 55 different languages.[84] Track listing The track listing is as it appears on the 2017 reissue by ozmarecords. No. Title Length "Greeting from Kurt Waldheim, Secretary-General of the United Nations" (by Various 1. 0:44 Artists) 2. "Greetings in 55 Languages" (by Various Artists) 3:46 3. "United Nations Greetings/Whale Songs" (by Various Artists) 4:04 4. "The Sounds of Earth" (by Various Artists) 12:19 "Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F Major, BWV 1047: I. Allegro (Johann Sebastian 5. 4:44 Bach)" (by Munich Bach Orchestra/Karl Richter) "Ketawang: Puspåwårnå (Kinds of Flowers)" (by Pura Paku Alaman Palace 6. 4:47 Orchestra/K.R.T. Wasitodipuro) 7. -

A List of Qin Recordings with a Spring Theme

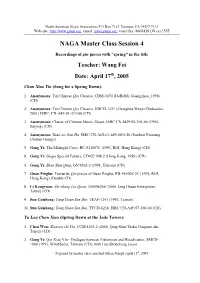

North American Guqin Association, P O Box 7113, Fremont, CA 94537-7113 Web site: http://www.guqin.org, email: [email protected], voice/fax: 8668419139 ext 1555 NAGA Master Class Session 4 Recordings of qin pieces with “spring” in the title Teacher: Wang Fei Date: April 17th, 2005 Chun Xiao Yin (Song for a Spring Dawn): 1. Anonymous: Ten Chinese Qin Classics, CDM-1074 (DoReMi, Guangzhou, 1998) (CD) 2. Anonymous: Ten Chinese Qin Classics, HDCD-1121 (Zhonghua Wenyi Chubanshe, 2001) ISRC: CN-A49-01-313-00 (CD) 3. Anonymous: Classic of Chinese Music: Guqin, ISRC CN-M29-94-306-00 (1994, Beijing) (CD) 4. Anonymous: Xiao’ao Jian Hu, ISRC CN-A65-01-649-00/A.J6 (Jiuzhou Yinxiang Chuban Gongsi) 5. Gong Yi: The Midnight Crow, RC-931007C (1993, ROI, Hong Kong) (CD) 8. Gong Yi: Guqin Special Feature, CD422 998-2 (Hong Kong, 1989) (CD) 6. Gong Yi: Shan Shui Qing, GN 9202-2 (1991, Taiwan) (CD) 7. Guan Pinghu: Favourite Qin pieces of Guan Pinghu, RB-951005-2C (1995, ROI, Hong Kong) (Double CD) 8. Li Kongyuan: Shi-shang Liu Quan, 200098268 (2000, Ling Hsuan Enterprises, Taibei) (CD) 9. Sun Guisheng: Yang Guan San Die, JRAF-1241 (1992, Taiwan) 10. Sun Guisheng: Yang Guan San Die, TYCD-0238, ISRC CN-A49-97-360-00 (CD) Yu Lou Chun Xiao (Spring Dawn at the Jade Tower): 1. Chen Wen: Xianwai zhi Yin, CCM 8103-2 (2000, Qing Shan Yishu Gongzuo-shi, Taipei) (CD) 2. Gong Yi: Qin Xiao Yin - Dialogue between Fisherman and Wood-cutter, SMCD- 1008 (1995, Wind/Solar, Taiwan) (CD); with Luo Shoucheng (xiao) Prepared by master class assistant Julian Joseph April 15th, 2005 North American Guqin Association, P O Box 7113, Fremont, CA 94537-7113 Web site: http://www.guqin.org, email: [email protected], voice/fax: 8668419139 ext 1555 3. -

Historical and Contemporary Development of the Chinese Zheng

Historical and Contemporary Development of the Chinese Zheng by Han Mei MA, The Music Research Institute of Chinese Arts Academy Beijing, People's Republic of China, 1995 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (School of Music) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October, 2000 ©HanMei 2000 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada DE-6 (2/88) ABSTRACT The zheng is a plucked, half-tube Chinese zither with a history of over two and a half millennia. During this time, the zheng, as one of the principal Chinese instruments, was used in both ensemble and solo performances, playing an important role in Chinese music history. Throughout its history, the zheng underwent several major changes in terms of construction, performance practice, and musical style. Social changes, political policies, and Western musical influences also significantly affected the development of the instrument in the twentieth century; thus the zheng and its music have been brought to a new stage through forces of modernization and standardization. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Date: 18 September 2018

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Date: 18 September 2018 Long March Symphony and Butterfly Lovers Violin Concerto - A National Day Celebration with Signature Chinese Symphonic Works (28 & 29 Sep) [18 September 2018, Hong Kong] Under the baton of Huang Yi, one of the brightest young conductors in China, the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra (HK Phil) will celebrate the National Day on 28 & 29 September 2018 with two great Chinese symphonic works - the romantic Butterfly Lovers Violin Concerto by Chen Gang and He Zhanhao featuring violinist Wang Zhijong, and the heroic Long March Symphony by Ding Shande, the former mentor of Chen and He - in the Hong Kong Cultural Centre Concert Hall. “The Long March Symphony is a piece representing the epoch of China.” - Yu Long The Long March Symphony by the legendary Chinese composer Ding Shande is one of his best known orchestral compositions. Taking the gallant story of the Chinese Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army marching over a distance of 25,000 miles, the Symphony is a deeply moving powerful piece. Under the baton of Huang Yi, the HK Phil ends the concert by revisiting this historic event. The Butterfly Lovers Violin Concerto is Chen Gang and He Zhanhao’s recreation of the romantic love story between Liang Shanbo and Zhu Yingtai. The Butterfly Lovers was hailed at its premiere as “a breakthrough in China’s symphonic music”. The piece incorporates Chinese elements and melodic phrases using western instrumentation. After 60 years since its premiere, “The Tchaikovsky Concerto of the East” will showcase the elegance of Chinese symphonic music through the sensitive representation of the sorrows of Zhu Yingtai. -

Preliminary Pages

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Ascending the Hall of Great Elegance: the Emergence of Drama Research in Modern China A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Hsiao-Chun Wu 2016 © Copyright by Hsiao-Chun Wu 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Ascending the Hall of Great Elegance: the Emergence of Drama Research in Modern China by Hsiao-Chun Wu Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2016, Professor Andrea Sue Goldman, Chair This dissertation captures a critical moment in China’s history when the interest in opera transformed from literati divertissement into an emerging field of scholarly inquiry. Centering around the activities and writings of Qi Rushan (1870-1962), who played a key role both in reshaping the modes of elite involvement in opera and in systematic knowledge production about opera, this dissertation explores this transformation from a transitional generation of theatrical connoisseurs and researchers in early twentieth-century China. It examines the many conditions and contexts in the making of opera—and especially Peking opera—as a discipline of modern humanistic research in China: the transnational emergence of Sinology, the vibrant urban entertainment market, the literary and material resources from the past, and the bodies and !ii identities of performers. This dissertation presents a critical chronology of the early history of drama study in modern China, beginning from the emerging terminology of genre to the theorization and the making of a formal academic discipline. Chapter One examines the genre-making of Peking Opera in three overlapping but not identical categories: temporal, geographical-political, and aesthetic. -

![[Ton]Spurensuche : Ernst Bloch Und Die Musik](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5658/ton-spurensuche-ernst-bloch-und-die-musik-1175658.webp)

[Ton]Spurensuche : Ernst Bloch Und Die Musik

Klappe hinten U4 U4 Buchrücken U1 U1 Klappe vorne KOLLEKTION MUSIKWISSENSCHAFT KOLLEKTION MUSIKWISSENSCHAFT MATTHIAS HENKE KOLLEKTION MUSIKWISSENSCHAFT HERAUSGEGEBEN VON MATTHIAS HENKE HERAUSGEGEBEN VON MATTHIAS HENKE HERAUSGEGEBEN VON MATTHIAS HENKE BAND 1 FRANCESCA VIDAL (HG.) BAND 1 MATTHIAS HENKE, FRANCESCA VIDAL (HG.) Matthias Henke, Francesca Vidal (Hg.) TON SPURENSUCHE Si! – das Motto der Kollektion Musikwissen- [Ton]Spurensuche [ ] ERNST BLOCH UND DIE MUSIK [TON]SPURENSUCHE schaft ist vielfältig. Zunächst spielt es auf Ernst Bloch und die Musik die Basis der Buchreihe an, den Universi- tätsverlag Siegen. Si! meint aber auch ein musikalisches Phänomen, heißt so doch der Spuren – so ist nicht nur ein Band mit den poetisch ver- Leitton einer Durskala. Last, not least will Ankündigung: trackten Erzählungen von Ernst Bloch überschrieben. FRANCESCA (HG.) VIDAL | Si! sich als Imperativ verstanden wissen, als [Ton]Spuren durchwirken vielmehr sein gesamtes Werk. ERNST BLOCH BAND 2 ein vernehmbares Ja zu einer Musikwissen- Demnach erstaunt es nicht, wenn des Philosophen Ver- Sara Beimdieke schaft, die sich zu dem ihr eigenen Potential hältnis zur Musik vielfach Gegenstand wissenschaftlicher „Der große Reiz des Kamera-Mediums“ UND DIE MUSIK bekennt, zu einer selbstbewussten Diszipli- Erörterungen war. Allerdings näherte man sich diesem Ernst Kreneks Fernsehoper Ausgerech- narität, die wirkliche Trans- oder Interdiszip- fast immer auf Metaebenen. Philologische Detailarbeit, net und Verspielt linarität erst ermöglicht. die etwa die Genesis -

China and the West: Music, Representation, and Reception

Revised Pages China and the West Revised Pages Wanguo Quantu [A Map of the Myriad Countries of the World] was made in the 1620s by Guilio Aleni, whose Chinese name 艾儒略 appears in the last column of the text (first on the left) above the Jesuit symbol IHS. Aleni’s map was based on Matteo Ricci’s earlier map of 1602. Revised Pages China and the West Music, Representation, and Reception Edited by Hon- Lun Yang and Michael Saffle University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Revised Pages Copyright © 2017 by Hon- Lun Yang and Michael Saffle All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2020 2019 2018 2017 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Yang, Hon- Lun, editor. | Saffle, Michael, 1946– editor. Title: China and the West : music, representation, and reception / edited by Hon- Lun Yang and Michael Saffle. Description: Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016045491| ISBN 9780472130313 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780472122714 (e- book) Subjects: LCSH: Music—Chinese influences. | Music—China— Western influences. | Exoticism in music.