On the Emergence of Tragedy in Kannada Literature T.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa Bk. 4

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa Bk. 4 Kisari Mohan Ganguli The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa Bk. 4, by Kisari Mohan Ganguli This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa Bk. 4 Author: Kisari Mohan Ganguli Release Date: April 16, 2004 [EBook #12058] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MAHABHARATAM, BK. 4 *** Produced by John B. Hare, Juliet Sutherland, David King, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa BOOK 4 VIRATA PARVA Translated into English Prose from the Original Sanskrit Text by Kisari Mohan Ganguli [1883-1896] Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. THE MAHABHARATA VIRATA PARVA SECTION I (_Pandava-Pravesa Parva_) OM! Having bowed down to Narayana, and Nara, the most exalted of male beings, and also to the goddess Saraswati, must the word _Jaya_ be uttered. Janamejaya said, "How did my great-grandfathers, afflicted with the fear of Duryodhana, pass their days undiscovered in the city of Virata? And, O Brahman, how did the highly blessed Draupadi, stricken with woe, devoted to her lords, and ever adoring the Deity[1], spend her days unrecognised?" [1] _Brahma Vadini_--Nilakantha explains this as _Krishna-kirtanasila._ Vaisampayana said, "Listen, O lord of men, how thy great grandfathers passed the period of unrecognition in the city of Virata. -

Transition Into Kaliyuga: Tossups on Kurukshetra

Transition Into Kaliyuga: Tossups On Kurukshetra 1. On the fifteenth day of the Kurukshetra War, Krishna came up with a plan to kill this character. The previous night, this character retracted his Brahmastra [Bruh-mah-struh] when he was reprimanded for using a divine weapon on ordinary soldiers. After Bharadwaja ejaculated into a vessel when he saw a bathing Apsara, this character was born from the preserved semen. Because he promised that Arjuna would be the greatest archer in the world, this character demanded that (*) Ekalavya give him his right thumb. This character lays down his arms when Yudhishtira [Yoo-dhish-ti-ruh] lied to him that his son is dead, when in fact it was an elephant named Ashwatthama that was dead.. For 10 points, name this character who taught the Pandavas and Kauravas military arts. ANSWER: Dronacharya 2. On the second day of the Kurukshetra war, this character rescues Dhristadyumna [Dhrish-ta-dyoom-nuh] from Drona. After that, the forces of Kalinga attack this character, and they are almost all killed by this character, before Bhishma [Bhee-shmuh] rallies them. This character assumes the identity Vallabha when working as a cook in the Matsya kingdom during his 13th year of exile. During that year, this character ground the general (*) Kichaka’s body into a ball of flesh as revenge for him assaulting Draupadi. When they were kids, Arjuna was inspired to practice archery at night after seeing his brother, this character, eating in the dark. For 10 points, name the second-oldest Pandava. ANSWER: Bhima [Accept Vallabha before mention] 3. -

Rajaji-Mahabharata.Pdf

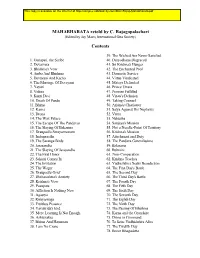

MAHABHARATA retold by C. Rajagopalachari (Edited by Jay Mazo, International Gita Society) Contents 39. The Wicked Are Never Satisfied 1. Ganapati, the Scribe 40. Duryodhana Disgraced 2. Devavrata 41. Sri Krishna's Hunger 3. Bhishma's Vow 42. The Enchanted Pool 4. Amba And Bhishma 43. Domestic Service 5. Devayani And Kacha 44. Virtue Vindicated 6. The Marriage Of Devayani 45. Matsya Defended 7. Yayati 46. Prince Uttara 8. Vidura 47. Promise Fulfilled 9. Kunti Devi 48. Virata's Delusion 10. Death Of Pandu 49. Taking Counsel 11. Bhima 50. Arjuna's Charioteer 12. Karna 51. Salya Against His Nephews 13. Drona 52. Vritra 14. The Wax Palace 53. Nahusha 15. The Escape Of The Pandavas 54. Sanjaya's Mission 16. The Slaying Of Bakasura 55. Not a Needle-Point Of Territory 17. Draupadi's Swayamvaram 56. Krishna's Mission 18. Indraprastha 57. Attachment and Duty 19. The Saranga Birds 58. The Pandava Generalissimo 20. Jarasandha 59. Balarama 21. The Slaying Of Jarasandha 60. Rukmini 22. The First Honor 61. Non-Cooperation 23. Sakuni Comes In 62. Krishna Teaches 24. The Invitation 63. Yudhishthira Seeks Benediction 25. The Wager 64. The First Day's Battle 26. Draupadi's Grief 65. The Second Day 27. Dhritarashtra's Anxiety 66. The Third Day's Battle 28. Krishna's Vow 67. The Fourth Day 29. Pasupata 68. The Fifth Day 30. Affliction Is Nothing New 69. The Sixth Day 31. Agastya 70. The Seventh Day 32. Rishyasringa 71. The Eighth Day 33. Fruitless Penance 72. The Ninth Day 34. Yavakrida's End 73. -

The Role of Women in the Mahabharata

THE ROLE OF WOMEN IN THE MAHABHARATA The role of women in the Mahabharata makes an interesting study providing insight into the strengths and weaknesses of their character. In this epic, four women play crucial parts in the course of events. The first is Satyavati who was the daughter of the chieftain of fishermen. As a young maiden, while ferrying sage Parasara across a river, he fell in love with her. She bore him a son, Vyasa. He was brought up as an ascetic sage, but before he returned to forest life, he promised his mother he would come and help her whenever she faced difficulty. Later, the emperor Santanu fell in love with her. Her father consented to the marriage only on condition that her children would inherit the throne. Santanu’s older son, the crown prince Bhishma, not only voluntarily relinquished his right but also took the vow that he would remain celibate so that he could not have any children who might lay claim to the throne in the future. After Santanu passed away, Satyavati’s two sons died young. The older one was unmarried, and the younger had two wives, Ambika and Ambalika, who were childless. This created a crisis for there was no legal heir to the Kuru throne. Bhishma did not relent from his vow because he considered it sacred. At this juncture, Satyavati sent for her son Vyasa, who promptly responded per his earlier promise. Satyavati said the problem could be solved by his fathering a child through each of the two young widows. -

Unit 10 Emergence of Rashtrakutas*

History of India from C. 300 C.E. to 1206 UNIT 10 EMERGENCE OF RASHTRAKUTAS* Structure 10.0 Objectives 10.1 Introduction 10.2 Historical Backgrounds of the Empire 10.3 The Rashtrakuta Empire 10.4 Disintegration of the Empire 10.5 Administration 10.6 Polity, Society, Religion, Literature 10.7 Summary 10.8 Key Words 10.9 Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises 10.10 Suggested Readings 10.0 OBJECTIVES In this Unit, we will discuss about the origin and emergence of the Rashtrakutas and the formation of Rashtrakuta empire. Later, we will also explore the organization and nature of Rashtrakuta state with social, religious, educational, cultural achievements during the Rashtrakutas. After studying the Unit, you will be able to learn about: major and minor kingdoms that were ruling over different territories of south India between 8th and 11th centuries; emergence of the Rashtrakutas as a dominant power in Deccan; the process of the formation of Rashtrakuta empire and contributions of different kings; the nature of early medieval polity and administration in the Deccan; significant components of the feudal political structure such as ideological bases, bureaucracy, military, control mechanism, villages etc.; and social, religious, educational, architectural and cultural developments within the Rashtrakuta empire. 10.1 INTRODUCTION India witnessed three powerful kingdoms between c. 750 and 1000 CE: Pala empire, Pratihara empire and Rashtrakuta empire in south India. These kingdoms fought each other to establish their respective hegemony which was the trend of early medieval India. Historian Noboru Karashima treats the empire as a new type of state, i.e. -

Pattadakal Text 3

1 ŚAIVA MONUMENTS at PAṬṬ ADAKAL Vasundhara Filliozat architecture by Pierre-Sylvain Filliozat 2 Scheme of transliteration from n āgar ī and kanna ḍa scripts Special n āgar ī letters ° ā £ ī • ū ¶ ṛ ṝ ḷ ṅ ñ ṭ ṭh – ḍ — ḍh “ ṇ ś ṣ Special kanna ḍa letters K ē N ō ¼ ḷ 3 S TABLE OF CONTENTS List of figures Introduction I. History History and chronology of Calukya kings Pulike śin II (A.D. 610-642) Vikram āditya II II. Architecture The site of Pa ṭṭ adakal The Karn āṭa-Nāgara temples at Pa ṭṭ adakal The temple of K āḍasiddhe śvara The temple of Jambuli ṅge śvara The temple of K āśī vi śvan ātha The temple of Galagan ātha The temple of P āpan ātha (M ūlasth ānamah ādeva) Miniature temples at Pa ṭṭ adakal The Candra śekhara temple The Karn āṭa-Dr āvi ḍa monuments at Pa ṭṭ adakal The temple of Vijaye śvara (Sa ṃgame śvara) The temple of Loke śvara (Vir ūpākṣa) Pr āsāda Interior Pr āsāda Exterior The Temple of Trailokye śvara (Mallik ārjuna) III. Iconography The temple of Vijaye śvara The Temple of Loke śvara External façades Loke śvara Temple, interior The temple of Trailokye śvara The temple of K āśī vi śve śvara The temple of P āpan ātha The temple of K āḍasiddhe śvara The temple of Jambuli ṅge śvara The temple of Galagan ātha IV. Epigraphy V. Conclusion Works referred to Glossary Glossary of special words in inscriptions Index 4 List of figures Photographs are by the authors assisted by Shalva Pillai Iyengar, unless otherwise stated. -

1 Component-I (A) – Personal Details

Component-I (A) – Personal details: 1 Component-I (B) – Description of module: Subject Name Indian Culture Paper Name Outlines of Indian History Module Name/Title Major dynasties of south India (753 – 1300 ce) Module Id I C/ OIH/ 17 Pre requisites Knowledge in the political history of South India Objectives To study the history of major dynasties of South India and their contribution to Indian Culture Keywords Rashtrakutas / Chalukyas of Kalyani / Yadavas/ Kakatiya / Hoysala/ Pandya E-text (Quadrant-I) 1. Introduction The Political History of Deccan between 753 – 1300 CE was marked by the ascendency of the Rashtrakutas of Manyaketa, emergence of Chola power, the Chalukyas of Kalyani and their subordinates. One of the kingdoms that rose to power on the ruins of the Chaluykas of Badami was the Rashtrakutas. Later, the country south of Tungabhadra was united as one state for nearly two centuries under Cholas of Tanjore and Chalukyas of Kalyani. Towards the close of the twelfth century, the two major powers-the Cholas and Chalukyas of Kalyani had became thoroughly exhausted by their conflicts and were on their decline. Their subordinate powers were started to show their new vigor and were ready to take advantage of the weakening of their suzerains and proclaimed independence. The Yadavas of Devagiri, the Kakatiyas of Warangal, the Hoysalas of Dwarasamudra and the Pandyas of Madurai constitute important political forces during 12th and 13th Centuries. 2. Topic I : Rashtrakutas (753 to 973 CE) Rashtrakutas were the important dynasty ruling over large parts of the Indian Subcontinent for 220 years from 753 to 973 CE with their capital from Manyakheta (Malkhed in Gulbarga district). -

Draupadi and Dhrishtadyumna

דראופדי http://img2.tapuz.co.il/CommunaFiles/34934883.pdf دراوبادي دروپدی द्रौपदी د ر وپد ی http://uh.learnpunjabi.org/default.aspx द्रौपदी ਦਰੋਪਤੀ http://h2p.learnpunjabi.org/default.aspx دروپتی فرشتہ ਦਰੋਪਤੀ ਫ਼ਰਰਸ਼ਤਾ http://g2s.learnpunjabi.org/default.aspx DRUPADA… Means "wooden pillar" or "firm footed" in Sanskrit. In the Hindu epic the 'Mahabharata' this is the name of a king of Panchala, the father of Draupadi and Dhrishtadyumna http://www.behindthename.com/name/drupada DRAUPADI Means "daughter of DRUPADA" in Sanskrit. http://www.behindthename.com/name/draupadi Draupadi - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Draupadi Draupadi From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Draupadi (Sanskrit: 6ौपदी , draupad ī, Sanskrit pronunciation: [d ̪ rəʊ pəd̪ i]) is described as the chief female Draupadi protagonist or heroine in the Hindu epic, Mahabharata .[1] According to the epic, she is the "fire born" daughter of Drupada, King of Panchala and also became the common wife of the five Pandavas. She was the most beautiful woman of her time. Draupadi had five sons; one by each of the Pandavas: Prativindhya from Yudhishthira, Sutasoma from Bheema, Srutakarma from Arjuna, Satanika from Nakula, and Srutasena from Sahadeva. Some people say that she too had two daughters after the Upapandavas, Shutanu from Yudhishthira and Pragiti from Arjuna although this is a debatable concept in the Mahabharata. Draupadi is considered as one of the Panch-Kanyas or Five Virgins. [2] She is also venerated as a village goddess Draupadi Amman. Draupadi, -

Mahabharatha Tatparya Nirnaya Agnatavasa of Pandavas the Events

Mahabharatha Tatparya Nirnaya Agnatavasa of Pandavas The events of Virataparva that relate to the agnatavasa of Pandavas are described in 23rd chapter. After completing the twelve years period of Vanavasa Pandavas took leave of Dhaumya, other sages and Brahman’s and made up their mind to undergo agnatavasa. They went to capital city of Virata. Before they entered the city they hid their weapons on a Sami tree in the outskirts of the city. The five Pandavas assumed the form of an ascetic, a cook, a eunuch, a charioteer, and a cowherd respectively. Draupadi assumed the form of Sairandhri i.e. a female artisan. Bhima assumed the form of cook for two reasons i) He never took food prepared by others ii) He did not want to reveal his great knowledge by assuming a Brahmana form. During their Agnatavasa they did not serve Virata or any other person. The younger brothers of Yudhishtira served Lord Hari and their eldest brother Yudhishtira in whom also God was present by the name of Yudhishtira One day a wrestler who had become invincible by the boon of Siva came to Virata's city. The wrestlers maintained by Virata were not able to meet his challenge. The ascetic i.e.Yudhishtira suggested to king Virata that the cook who had the skill in wrestling well could be asked to wrestle with him. The cook i.e., Bhima, wrestled with him and killed. Kichaka is Killed Ten months after Pandava's stay at Virata's palace, Kichaka, the brother of Queen Sudesna came. He was away to conquer the neighboring kings. -

The Mahabharata

BHAGAVAD GITA The Global Dharma for the Third Millennium Appendix Translations and commentaries by Parama Karuna Devi Copyright © 2015 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved. ISBN-13: 978-1517677428 ISBN-10: 1517677424 published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center phone: +91 94373 00906 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com © 2015 PAVAN Correspondence address: PAVAN House Siddha Mahavira patana, Puri 752002 Orissa Gita mahatmya by Adi Shankara VERSE 1 gita: Bhagavad gita; sastram: the holy scripture; idam: this; punyam: accruing religious and karmic merits; yah: one who; pathet: reads; prayatah: when departed; puman: a human being; visnoh: of Vishnu; padam: the feet; avapnoti: attains; bhaya: fear; soka adi: sadness etc; varjitah: completely free. This holy scripture called Bhagavad gita is (the source of) great religious and karmic merits. One who reads it leaves (the materialistic delusion, the imprisonment of samsara, etc)/ after leaving (this body, at the time of death) attains the abode of Vishnu, free from fear and sadness. Parama Karuna Devi VERSE 2 gita adhyayana: by systematic study of Bhagavad gita; silasya: by one who is well behaved; pranayama: controlling the life energy; parasya: of the Supreme; ca: and; na eva: certainly not; santi: there will be; hi: indeed; papani: bad actions; purva: previous; janma: lifetimes; krtani: performed; ca: even. By systematically studying the Bhagavad gita, chapter after chapter, one who is well behaved and controls his/ her life energy is engaged in the Supreme. Certainly such a person becomes free from all bad activities, including those developed in previous lifetimes. VERSE 3 malanih: from impurities; mocanam: liberation; pumsam: a human being; jala: water; snanam: taking bath; dine dine: every day; 4 Appendix sakrid: once only; gita ambhasi: in the waters of the Bhagavad gita; snanam: taking bath; samsara: the cycle of conditioned life; mala: contamination; nasanam: is destroyed. -

Manu V. Devadevan a Prehistory of Hinduism

Manu V. Devadevan A Prehistory of Hinduism Manu V. Devadevan A Prehistory of Hinduism Managing Editor: Katarzyna Tempczyk Series Editor: Ishita Banerjee-Dube Language Editor: Wayne Smith Open Access Hinduism ISBN: 978-3-11-051736-1 e-ISBN: 978-3-11-051737-8 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. © 2016 Manu V. Devadevan Published by De Gruyter Open Ltd, Warsaw/Berlin Part of Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Managing Editor: Katarzyna Tempczyk Series Editor:Ishita Banerjee-Dube Language Editor: Wayne Smith www.degruyteropen.com Cover illustration: © Manu V. Devadevan In memory of U. R. Ananthamurthy Contents Acknowledgements VIII A Guide to Pronunciation of Diacritical Marks XI 1 Introduction 1 2 Indumauḷi’s Grief and the Making of Religious Identities 13 3 Forests of Learning and the Invention of Religious Traditions 43 4 Heredity, Genealogies, and the Advent of the New Monastery 80 5 Miracles, Ethicality, and the Great Divergence 112 6 Sainthood in Transition and the Crisis of Alienation 145 7 Epilogue 174 Bibliography 184 List of Tables 196 Index 197 Acknowledgements My parents, Kanakambika Antherjanam and Vishnu Namboodiri, were my first teachers. From them, I learnt to persevere, and to stay detached. This book would not have been possible without these fundamental lessons. -

Lights Camera Pack Up

SON-IN-LAW OF NCP CORONA CATASTROPHE LEADER HELD BY ED INDIA UP Mumbai: The Enforcement Direc- torate (ED) on Wednesday arrested Girish Chaudhri, son-in-law of NCP 43,733 120 leader Eknath Khadse, in connec- new cases new cases tion with a case pertaining to a 2016 land deal in Pune. He was LUCKNOW l THURSDAY, JULY 8, 2021 l Pages 12 l 3.00 RNI NO. UPENG/2020/04393 l Vol 1 l Issue No. 207 11 930 new fatalities sent to ED custody till July 12. OUR EDITIONS: JAIPUR, AHMEDABAD & LUCKNOW www.fi rstindia.co.in I www.fi rstindia.co.in/epaper/ I twitter.com/thefi rstindia I facebook.com/thefi rstindia I instagram.com/thefi rstindia new fatalities I congratulate all the colleagues who have taken oath today and wish them the very best for their ministerial tenure. We will continue working to fulfi l aspirations of the people and build a strong and prosperous India, tweeted Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Wednesday. In a major overhaul of Cabinet FAB 4 & MORE THAT WENT DOWN 1 Sonowal, Scindia brought in as 12 ministers exit This is the first reshuffle in the 2 Council of Ministers by Prime PM’s MODIFIED Minister Modi since he assumed charge 43 ministers take oath for a second term in May 2019 in a bid to revamp Ahead of the oath-taking ceremony of new Kiren Rijiju, R K Singh, Hardeep Singh administration inductees into the Union cabinet, a total of 12 3 Puri, Mansukh Mandaviya, Parshottam CABINET ministers submitted their resignation, including New Delhi: In a major FIRST MEET TODAY AMIT SHAH MADE MINISTER Union Health Minister Harsh Vardhan, Minister Rupala, G Kishan Reddy and Anurag Thakur overhaul, Prime Minister for Law and Electronics and IT Ravi Shankar Narendra Modi on Wednes- New Delhi: The fi rst meeting OF CO-OPERATION, MANSUKH were elevated to the Cabinet level of the renewed Union Prasad and Education Minister Ramesh day brought in Sarbananda MANDAVIYA IS HEALTH MIN Pokhriyal.