Pattadakal Text 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karnataka Tourism Vision Group 2014 Report

Karnataka Tourism Vision group 2014 report KARNATAKA TOURISM VISION GROUP (KTVG) Recommendations to the GoK: Jan 2014 Task force KTVG Karnataka Tourism Vision Group 2014 Report 1 FOREWORD Tourism matters. As highlighted in the UN WTO 2013 report, Tourism can account for 9% of GDP (direct, indirect and induced), 1 in 11 jobs and 6% of world exports. We are all aware of amazing tourist experiences globally and the impact of the sector on the economy of countries. Karnataka needs to think big, think like a Nation-State if it is to forge ahead to realise its immense tourism potential. The State is blessed with natural and historical advantage, which coupled with a strong arts and culture ethos, can be leveraged to great advantage. If Karnataka can get its Tourism strategy (and brand promise) right and focus on promotion and excellence in providing a wholesome tourist experience, we believe that it can be among the best destinations in the world. The impact on job creation (we estimate 4.3 million over the next decade) and economic gain (Rs. 85,000 crores) is reason enough for us to pay serious attention to focus on the Tourism sector. The Government of Karnataka had set up a Tourism Vision group in Oct 2013 consisting of eminent citizens and domain specialists to advise the government on the way ahead for the Tourism sector. In this exercise, we had active cooperation from the Hon. Minister of Tourism, Mr. R.V. Deshpande; Tourism Secretary, Mr. Arvind Jadhav; Tourism Director, Ms. Satyavathi and their team. The Vision group of over 50 individuals met jointly in over 7 sessions during Oct-Dec 2013. -

Linguistic Ecology of Karnataka (A State in the Union of India)

================================================================= Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 19:7 July 2019 ================================================================ Linguistic Ecology of Karnataka (A State in the Union of India) Prof. B. Mallikarjun Former Director Centre for Classical Kannada Central University of Karnataka Kadaganchi, Aland Road, Kalaburagi District - 585311. KARNATAKA, INDIA [email protected] ================================================================= Introduction First let us look at two concepts. Landscape is ‘all the visible features of an area of land, often considered in terms of their aesthetic appeal.’ Ecology ‘is the relationships between the air, land, water, animals, plants etc., usually of a particular area, or the scientific study of this.’ It takes hundred or thousand or more years to bring changes in the grammatical structure of a language. Even after that time the change may remain incomplete. This refers to the internal changes in a language. But the economic, social and political and policy decisions in a country do not need more time to modify the linguistic demography. This reflects the external changes relating to a language. India became independent in 1947, conducted its first census after independence in 1951. It reorganised its administrative units on linguistic lines in 1956 and conducted the first census after reorganisation in 1961. The census data of 2011 helps us to understand the changes that have taken place in fifty years since 1971. This paper explores the linguistic demography of Karnataka, one of the states in India in terms of its landscape and ecology using the census data of 50 years from 1971 to 2011. Karnataka Karnataka is one of the states and union territories in southern part of India. -

91 44 2744 2160 Email: [email protected] Web: (Formerly Hi Tours Mamallapuram Pvt Ltd)

Tel: + 91 44 2744 3260 / 2744 3360 / 2744 2460 Fax: 91 44 2744 2160 Email: [email protected] Web: www.travelxs.in (Formerly Hi Tours Mamallapuram Pvt Ltd) TOUR NAME: CENTRAL INDIA TOUR TOUR DAYS: 28 NIGHTS, 29 DAYS ROUTE : DELHI (ARRIVAL) – AGRA – ORCHHA – KHAJURAHO –SANCHI - UJJAIN - MANDU - MAHESHWAR – OMKARESHWAR - AJANTA - AURANGABAD - HYDERABAD – BIJAPUR – BADAMI – HAMPI – CHITRADURGA - SHARAVANBELAGOLA – BANGALORE TOUR LODGING INFO: 27 Nights Hotels, 01 Overnight Trains Accommodation will be provided on room with breakfast basis. For Lunch and dinner there would be an additional supplement. Our aforementioned quoted tour cost is based on Standard Category. Hotel list is as follows:- PLACES COVERED NUMBER OF NIGHTS STANDARD HOTELS DELHI 02 NIGHTS ASTER INN AGRA 02 NIGHTS ROYALE RESIDENCY ORCHHA 02 NIGHT SHEESH MAHAL KHAJURAHO 02 NIGHTS USHA BUNDELA SANCHI 02 NIGHTS GATEWAY RETREAT (MPTDC HOTEL) UJJAIN 02 NIGHTS SHIPRA RESIDENCY (MPTDC HOTEL) MANDU 03 NIGHTS MALWA RESORT (MPTDC HOTEL) MAHESHWAR 01 NIGHT NARMADA RESORT (MPTDC HOTEL) OMKARESHWAR 01 NIGHT NARMADA RESORT (MPTDC HOTEL) AJANTA 01 NIGHT FARDAPUR (MTDC HOTEL) AURANGABAD 01 NIGHT NEW BHARATI OVERNIGHT TRAIN 01 NIGHT HYDERABAD 02 NIGHTS HOTEL GOLKONDA BIJAPUR 01 NIGHT MADHUVAN INTERNATIONAL BADAMI 02 NIGHTS BADAMI COURT HAMPI 01 NIGHT HAMPI BOULDERS CHITRADURGA 01 NIGHT NAVEEN RESIDENCY SHARAVANBELAGOLA 01 NIGHT HOTEL RAGHU TOUR PACKAGE INCLUDES: - Accommodation on twin sharing basis. - Daily Buffet Breakfast. - All transfers / tours and excursions by AC chauffeur driven vehicle. - 2nd AC Sleeper Class Train ticket from Aurangabad - Hyderabad - All currently applicable taxes. TOUR PACKAGE DOES NOT INCLUDE: - Meals at hotels except those listed in above inclusions. - Entrances at all sight seeing spots. -

Nanjanagud Bar Association : Nanjanagud Taluk : Nanjanagud District : Mysuru

3/17/2018 KARNATAKA STATE BAR COUNCIL, OLD KGID BUILDING, BENGALURU VOTER LIST POLING BOOTH/PLACE OF VOTING : NANJANAGUD BAR ASSOCIATION : NANJANAGUD TALUK : NANJANAGUD DISTRICT : MYSURU SL.NO. NAME SIGNATURE K S Jayadevappa PLD/1/58 1 S/O K S Basavaiah 12th Cross, R P Road Extension, Najnjanagud NANJANAGUD MYSURU 571301 MUNISUVRATHA C P MYS/621/62 S/O PADMANABHAIAH 2 15TH CROSS 3RD MAIN ROAD NANJANGUD MYSURU NANJANAGUD MYSURU 571301 YOGESH B. KAR/23/77 3 S/O BASAVARAJAPPA M S K S R T C BUS STAND NANJUNGUD MYSURU NANJANAGUD MYSURU 571 301 SETHU RAO M.J. KAR/352/77 4 S/O M.JAGANNATH 3324 12TH CROSS, SRIKANTAPURI NANJANAGUD MYSURU 571 301 1/26 3/17/2018 VENKAPPA GOWDA M KAR/475/79 5 S/O M.ANNAPPA GOWDA MYSURU CITY NANJANAGUD MYSURU 570005 SHANKARAPPA C M KAR/576/79 6 S/O B MUDDUMALLAPPA GEJJIGANAHALLI POST NANJANAGUD MYSURU PALANETRA KAR/333/80 S/O LATE BASAVARAJAPPA 7 1424 S-3, SUNRISE APARTMENT, 7TH CROSS, K.M PURAM NANJANAGUD MYSURU 571301 SRIKANTA PRASAD N KAR/164/81 8 S/O NAGARAJ P (LATE) R P ROAD , NANJANAGUD TOWN NANJANAGUD MYSURU 571 301 VRUSHOBHENDRA PRASAD K KAR/233/81 S/O KUMARASWAMY SWAMY 9 20/1 7TH MAIN SWIMMING POOL ROAD SARASWATHI PURAM NANJANAGUD MYSURU 2/26 3/17/2018 BASAVANNA S KAR/182/82 10 S/O SOMAPPA UMMATHUR, CHAMARAJANAGAR NANJANAGUD MYSURU 571301 MAHADEVA KUMAR E KAR/427/83 S/O EREGOWDA 11 NO 3385 ,'ISHANI NILAY' ,13TH CROSS, B V PANDITH ROAD, R P MAIN ROAD NANJANAGUD MYSURU 571 301 GIRIRAJA S KAR/165/85 12 S/O SUBRAYAPPA HULLAHALLI NANJANAGUD MYSURU 571 301 GANESH MURTHY. -

Shiva's Waterfront Temples

Shiva’s Waterfront Temples: Reimagining the Sacred Architecture of India’s Deccan Region Subhashini Kaligotla Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 © 2015 Subhashini Kaligotla All rights reserved ABSTRACT Shiva’s Waterfront Temples: Reimagining the Sacred Architecture of India’s Deccan Region Subhashini Kaligotla This dissertation examines Deccan India’s earliest surviving stone constructions, which were founded during the 6th through the 8th centuries and are known for their unparalleled formal eclecticism. Whereas past scholarship explains their heterogeneous formal character as an organic outcome of the Deccan’s “borderland” location between north India and south India, my study challenges the very conceptualization of the Deccan temple within a binary taxonomy that recognizes only northern and southern temple types. Rejecting the passivity implied by the borderland metaphor, I emphasize the role of human agents—particularly architects and makers—in establishing a dialectic between the north Indian and the south Indian architectural systems in the Deccan’s built worlds and built spaces. Secondly, by adopting the Deccan temple cluster as an analytical category in its own right, the present work contributes to the still developing field of landscape studies of the premodern Deccan. I read traditional art-historical evidence—the built environment, sculpture, and stone and copperplate inscriptions—alongside discursive treatments of landscape cultures and phenomenological and experiential perspectives. As a result, I am able to present hitherto unexamined aspects of the cluster’s spatial arrangement: the interrelationships between structures and the ways those relationships influence ritual and processional movements, as well as the symbolic, locative, and organizing role played by water bodies. -

Jakanachari: an Artisan Or a Collective Genius?

Jakanachari: An artisan or a collective genius? deccanherald.com/spectrum/jakanachari-an-artisan-or-a-collective-genius-862581.html July 18, 2020 1/10 2/10 3/10 4/10 5/10 6/10 Myths about legendary artisans who built spectacular temples abound in many parts of India. Those mysterious, faceless personalities who built the considerable architectural wealth of the Indian subcontinent have always fascinated us lucky inheritors of this treasure. In Kerala, we have the legendary Peruntacchan, to whom many a temple has been attributed, and everyone in Odisha is familiar with Dharmapada, the young son of the chief architect of the Sun Temple at Konark, who solved the puzzle of the crowning stone of the temple shikhara. And in Karnataka, we have the legendary Jakanachari, whose chisel is said to have given form to innumerable temples of this land. Most of these artisan-myths appear to have the same plot, with more than a whiff of tragedy. Peruntacchan, supposedly jealous of the rising talents of his own son, accidentally drops a chisel while the duo was working on the timber roof of a temple, killing the son. Dharmapada, who solves the riddle which allowed the completion of the tower of the Konark Temple, which had vexed twelve thousand artisans, sacrifices himself so that their honour is not diminished in the eyes of the King. There are other myths in other lands which echo this tragic course of events. In Tamil country, the unfinished state of the rock-cut temple called Vettuvan Kovil is believed to be the consequence of the architect of this structure striking his son dead, because the son had boasted upon finishing his own temple project ahead of the father. -

Hoysala King Ballala Iii (1291-1342 A.D)

FINAL REPORT UGC MINOR RESEARCH PROJECT on LIFE AND ACHIEVEMENTS: HOYSALA KING BALLALA III (1291-1342 A.D) Submitted by DR.N.SAVITHRI Associate Professor Department of History Mallamma Marimallappa Women’s Arts and Commerce College, Mysore-24 Submitted to UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION South Western Regional Office P.K.Block, Gandhinagar, Bangalore-560009 2017 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First of all, I would like to Express My Gratitude and Indebtedness to University Grants Commission, New Delhi for awarding Minor Research Project in History. My Sincere thanks are due to Sri.Paramashivaiah.S, President of Marimallappa Educational Institutions. I am Grateful to Prof.Panchaksharaswamy.K.N, Honorary Secretary of Marimallappa Educational Institutions. I owe special thanks to Principal Sri.Dhananjaya.Y.D., Vice Principal Prapulla Chandra Kumar.S., Dr.Saraswathi.N., Sri Purushothama.K, Teaching and Non-Teaching Staff, members of Mallamma Marimallappa Women’s College, Mysore. I also thank K.B.Communications, Mysore has taken a lot of strain in computerszing my project work. I am Thankful to the Authorizes of the libraries in Karnataka for giving me permission to consult the necessary documents and books, pertaining to my project work. I thank all the temple guides and curators of minor Hoysala temples like Belur, Halebidu. Somanathapura, Thalkad, Melkote, Hosaholalu, kikkeri, Govindahalli, Nuggehalli, ext…. Several individuals and institution have helped me during the course of this study by generously sharing documents and other reference materials. I am thankful to all of them. Dr.N.Savithri Place: Date: 2 CERTIFICATE I Dr.N. Savithri Certify that the project entitled “LIFE AND ACHIEVEMENTS: HOYSALA KING BALLALA iii (1299-1342 A.D)” sponsored by University Grants Commission New Delhi under Minor Research Project is successfully completed by me. -

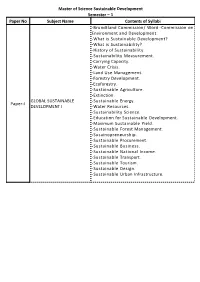

Master of Science Sustainable Development Semester – 1 Paper

Master of Science Sustainable Development Semester – 1 Paper No Subject Name Contents of Syllabi -Brundtland Commission/ Word -Commission on Environment and Development. -What is Sustainable Development? -What is Sustainability? -History of Sustainability. -Sustainability Measurement. -Carrying Capacity. -Water Crisis. -Land Use Management. -Forestry Development. -Ecoforestry. -Sustainable Agriculture. -Extinction. GLOBAL SUSTAINABLE -Sustainable Energy. Paper-I DEVELOPMENT I -Water Resources. -Sustainability Science. -Education for Sustainable Development. -Maximum Sustainable Yield. -Sustainable Forest Management. -Susainopreneurship. -Sustainable Procurement. -Sustainable Business. -Sustainable National Income. -Sustainable Transport. -Sustainable Tourism. -Sustainable Design. -Sustainable Urban Infrastructure. Master of Science Sustainable Development -What is Biodiversity? -Measurement of Biodiversity. -Species Richness. -Shannon Index. -2010 Biodiversity Indicators- Partnership. -Evolution. -Evolutionary Thought. -How does Evolution Occur? -Timeline of Evolution. BIODIVERSITY -Social Effect of Evolutionary Theory. Paper-II CONSERVATION & -Objections of Evolution. MANAGEMENT I -Population Genetics. -Genetics. -Heredity. -Mutation. -Molecular Evolution. -Genetic Recombination. -Sexual Reproduction. -Gene Flow. -Hybrid. -What is Energy? -History of Energy. -Timeline of Thermodynamics. -Units of Energy. -Potential Energy. -Elastic Energy. -Kinetic Energy. -Internal Energy. -Electromagnetism. -Electricity. GLOBAL ENERGY POLICIES Paper-III -

GONE to the DOGS in ANCIENT INDIA Willem Bollée

GONE TO THE DOGS IN ANCIENT INDIA Willem Bollée Gone to the Dogs in ancient India Willem Bollée Published at CrossAsia-Repository, Heidelberg University Library 2020 Second, revised edition. This book is published under the license “Free access – all rights reserved”. The electronic Open Access version of this work is permanently available on CrossAsia- Repository: http://crossasia-repository.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/ urn: urn:nbn:de:bsz:16-crossasiarep-42439 url: http://crossasia-repository.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/4243 doi: http://doi.org/10.11588/xarep.00004243 Text Willem Bollée 2020 Cover illustration: Jodhpur, Dog. Image available at https://pxfuel.com under Creative Commons Zero – CC0 1 Gone to the Dogs in ancient India . Chienne de vie ?* For Johanna and Natascha Wothke In memoriam Kitty and Volpo Homage to you, dogs (TS IV 5,4,r [= 17]) Ο , , ! " #$ s &, ' ( )Plato , * + , 3.50.1 CONTENTS 1. DOGS IN THE INDUS CIVILISATION 2. DOGS IN INDIA IN HISTORICAL TIMES 2.1 Designation 2.2 Kinds of dogs 2.3 Colour of fur 2.4 The parts of the body and their use 2.5 BODILY FUNCTIONS 2.5.1 Nutrition 2.5.2 Excreted substances 2.5.3 Diseases 2.6 Nature and behaviour ( śauvana ; P āli kukkur âkappa, kukkur āna ṃ gaman âkāra ) 2.7 Dogs and other animals 3. CYNANTHROPIC RELATIONS 3.1 General relation 3.1.1 Treatment of dogs by humans 3.1.2 Use of dogs 3.1.2.1 Utensils 3.1.3 Names of dogs 2 3.1.4 Dogs in human names 3.1.5 Dogs in names of other animals 3.1.6 Dogs in place names 3.1.7 Treatment of humans by dogs 3.2 Similes -

The Evolution of the Temple Plan in Karnataka with Respect to Contemporaneous Religious and Political Factors

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 22, Issue 7, Ver. 1 (July. 2017) PP 44-53 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org The Evolution of the Temple Plan in Karnataka with respect to Contemporaneous Religious and Political Factors Shilpa Sharma 1, Shireesh Deshpande 2 1(Associate Professor, IES College of Architecture, Mumbai University, India) 2(Professor Emeritus, RTMNU University, Nagpur, India) Abstract : This study explores the evolution of the plan of the Hindu temples in Karnatak, from a single-celled shrine in the 6th century to an elaborate walled complex in the 16th. In addition to the physical factors of the material and method of construction used, the changes in the temple architecture were closely linked to contemporary religious beliefs, rituals of worship and the patronage extended by the ruling dynasties. This paper examines the correspondence between these factors and the changes in the temple plan. Keywords: Hindu temples, Karnataka, evolution, temple plan, contemporary beliefs, religious, political I. INTRODUCTION 1. Background The purpose of the Hindu temple is shown by its form. (Kramrisch, 1996, p. vii) The architecture of any region is born out of various factors, both tangible and intangible. The tangible factors can be studied through the material used and the methods of construction used. The other factors which contribute to the temple architecture are the ways in which people perceive it and use it, to fulfil the contemporary prescribed rituals of worship. The religious purpose of temples has been discussed by several authors. Geva [1] explains that a temple is the place which represents the meeting of the divine and earthly realms. -

Outline Itinerary

About the tour: This historic tour begins in I Tech city Bangalore and proceed to the former princely state Mysore rich in Imperial heritage. Visit intrinsically Hindu collection of temples at Belure, Halebidu, Hampi, Badami, Aihole & Pattadakal, to see some of India's most intricate historical stone carvings. At the end unwind yourself in Goa, renowned for its endless beaches, places of worship & world heritage architecture. Outline Itinerary Day 01; Arrive Bangalore Day 02: Bangalore - Mysore (145kms/ 3hrs approx) Day 03: Mysore - Srirangapatna - Shravanabelagola - Hassan (140kms/ 3hrs approx) Day 04; Hassan – Belur – Halebidu – Hospet/ Hampi (310kms – 6-7hrs approx) Day 05; Hospet & Hampi Day 06; Hospet - Lakkundi – Gadag – Badami (130kms/ 3hrs approx) Day 07; Badami – Aihole – Pattadakal – Badami (80kms/ round) Day 08; Badami – Goa (250kms/ 5hrs approx) Day 09; Goa Day 10; Goa Day 11; Goa – Departure House No. 1/18, Top Floor, DDA Flats, Madangir, New Delhi 110062 Mob +91-9810491508 | Email- [email protected] | Web- www.agoravoyages.com Price details: Price using 3 star hotels valid from 1st October 2018 till 31st March 2019 (5% Summer discount available from 1st April till travel being completed before 30th September 2018 on 3star hotels price) Per person price sharing DOUBLE/ Per person price sharing TRIPLE (room Per person price staying in SINGLE Particular TWIN rooms with extra bed) rooms rooms Currency INR Euro USD INR Euro USD INR Euro USD 1 person N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A ₹180,797 € 2,260 $2,825 2 person ₹96,680 € 1,208 -

Kannada Literature Syllabus

Kannada Literature Syllabus UPSC Civil Services Mains Exam is of Optional Subject and consists of 2 papers. Each paper is of 250 marks with a total of 500 marks. KANNADA PAPER-I (Answers must be written in Kannada) Section-A History of Kannada Language What is Language? General charecteristics of Language. Dravidian Family of Languages and its specific features, Antiquity of Kannada Language, Different Phases of its Development. Dialects of Kannada Language : Regional and Social Various aspects of development of Kannada Language : phonological and Semantic changes. Language borrowing. History of Kannada Literature Ancient Kannada literature : Influence and Trends. Poets for study : Specified poets from Pampa to Ratnakara Varni are to be studied in the light of contents, form and expression : Pampa, Janna, Nagachandra. Medieval Kannada literature : Influence and Trends. Vachana literature : Basavanna, Akka Mahadevi. Medieval Poets : Harihara, Ragha-vanka, Kumar-Vyasa. Dasa literature : Purandra and Kanaka. Sangataya : Ratnakaravarni Modern Kannada literature : Influence, trends and idealogies, Navodaya, Pragatishila, Navya, Dalita and Bandaya. Section-B Poetics and literary criticism : Definition and concepts of poetry : Word, Meaning, Alankara, Reeti, Rasa, Dhwani, Auchitya. Interpretations of Rasa Sutra. Modern Trends of literary criticism : Formalist, Historical, Marxist, Feminist, Post-colonial criticism. Cultural History of Karnataka Contribution of Dynasties to the culture of Karnataka : Chalukyas of Badami and Kalyani, Rashtrakutas, Hoysalas, Vijayanagara rulers, in literary context. Major religions of Karnataka and their cultural contributions. Arts of Karnataka : Sculpture, Architecture, Painting, Music, Dance-in the literary context. Unification of Karnataka and its impact on Kannada literature. PAPER-II (Answers must be written in Kannada) The paper will require first-hand reading of the Texts prescribed and will be designed to test the critical ability of the candidates.