Out of Tibet—Highlights of the Yak's Journey to the New World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wild Yak Bos Mutus in Nepal: Rediscovery of a Flagship Species

Mammalia 2015; aop Raju Acharya, Yadav Ghimirey*, Geraldine Werhahn, Naresh Kusi, Bidhan Adhikary and Binod Kunwar Wild yak Bos mutus in Nepal: rediscovery of a flagship species DOI 10.1515/mammalia-2015-0066 2009). It has also been believed to inhabit the lower eleva- Received April 15, 2015; accepted July 21, 2015 tion Altai ranges in Mongolia (Olsen 1990). The possible fossil of wild yak discovered in Nepal (Olsen 1990) provided historical evidence of the species’ Abstract: Wild yak Bos mutus is believed to have gone presence in the country. Schaller and Liu (1996) also extinct from Nepal. Various searches in the last decade stated the occurrence of the wild yak in Nepal. Wild failed to document its presence. In Humla district, far- yak is said to inhabit the areas north of the Himalayas western Nepal, we used observation from transects and (Jerdon 1874, Hinton and Fry 1923), which also include vantage points, sign survey on trails, and informal dis- Limi Valley. Skins and horns were sporadically discov- cussions to ascertain the presence of wild yak in 2013 ered by explorers in the Himalayan and trans-Himala- (May–June) and 2014 (June–July). Direct sightings of two yan region of the country. These include evidence of individuals and hoof marks, dung piles, pelts, and head three horns of the species (around four decades old) of an individual killed in 2012 confirmed its presence. that can still be found in Lo Manthang (two pairs of The wild yak has an uncertain national status with con- horn) and Tsaile (one pair of horns) of Upper Mustang firmed records only from Humla district. -

Phylogeographical Analyses of Domestic and Wild Yaks

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital.CSIC RIGIN AL Phylogeographical analyses of domestic AR TI C L E and wild yaks based on mitochondrial DNA: new data and reappraisal Zhaofeng Wang1†, Xin Shen2†, Bin Liu2†, Jianping Su3†, Takahiro Yonezawa4, Yun Yu2, Songchang Guo3, Simon Y. W. Ho5, Carles Vila` 6, Masami Hasegawa4 and Jianquan Liu1* 1Molecular Ecology Group, Key Laboratory of AB STRACT Arid and Grassland Ecology, School of Life Science, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, Aim We aimed to examine the phylogeographical structure and demographic 2 history of domestic and wild yaks ( ) based on a wide range of Gansu, China, Beijing Genomics Institute, Bos grunniens Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 101300, samples and complete mitochondrial genomic sequences. 3 China, Key Laboratory of Evolution and Location The Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau (QTP) of western China. Adaptation of Plateau Biota, Northwest Plateau Institute of Biology, Chinese Academy Methods All available D-loop sequences for 405 domesticated yaks and 47 wild of Sciences, Xining 810001, Qinghai, China, yaks were examined, including new sequences from 96 domestic and 34 wild yaks. 4School of Life Sciences, Fudan University, We further sequenced the complete mitochondrial genomes of 48 domesticated Shanghai 200433, China, 5Centre for and 21 wild yaks. Phylogeographical analyses were performed using the Macroevolution and Macroecology, Research mitochondrial D-loop and the total genome datasets. School of Biology, Australian National Results We recovered a total of 123 haplotypes based on the D-loop sequences University, Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia, in wild and domestic yaks. -

Structural Characterisation of Toll-Like Receptor 1 (TLR1) and Toll-Like

RVC OPEN ACCESS REPOSITORY – COPYRIGHT NOTICE This is the peer-reviewed, manuscript version of the following article: Woodman, S., Gibson, A. J., García, A. R., Contreras, G. S., Rossen, J. W., Werling, D. and Offord, V. (2016) 'Structural characterisation of Toll-like receptor 1 (TLR1) and Toll-like receptor 6 (TLR6) in elephant and harbor seals', Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology, 169, 10-14. The final version is available online via http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetimm.2015.11.006. © 2016. This manuscript version is made available under the CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The full details of the published version of the article are as follows: TITLE: Structural characterisation of Toll-like receptor 1 (TLR1) and Toll-like receptor 6 (TLR6) in elephant and harbor seals AUTHORS: Woodman, S., Gibson, A. J., García, A. R., Contreras, G. S., Rossen, J. W., Werling, D. and Offord, V. JOURNAL TITLE: Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology VOLUME: 169 PUBLISHER: Elsevier PUBLICATION DATE: January 2016 DOI: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2015.11.006 1 Structural characterisation of Toll-like receptor 1 (TLR1) and Toll-like receptor 6 (TLR6) in 2 elephant and harbor seals 3 4 Sally Woodman1,Amanda J. Gibson1, Ana Rubio García2, Guillermo Sanchez Contreras2, John W. 5 Rossen3, Dirk Werling1, Victoria Offord1,* 6 7 1Molecular Immunology Group, Department of Pathology and Pathogen Biology, Royal Veterinary 8 College, Hawkshead Lane, Hatfield, AL9 7TA, UK; 9 2Veterinary Department, Seal Rehabilitation and Research Centre (SRRC), Pieterburen, The 10 Netherlands; 11 3Department of Medical Microbiology, University of Groningen, University Medical Center 12 Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands; 13 * Corresponding author at the Research Support Office, Royal Veterinary College, Hawkshead Lane, 14 Hatfield, AL9 7TA, UK Tel: ++44 1707 667038; E-Mail: [email protected] 15 16 1 1 Abstract 2 Pinnipeds are a diverse clade of semi-aquatic mammals, which act as key indicators of ecosystem health. -

Genetic Variation of Mitochondrial DNA Within Domestic Yak Populations J.F

Genetic variation of mitochondrial DNA within domestic yak populations J.F. Bailey,1 B. Healy,1 H. Jianlin,2 L. Sherchand,3 S.L. Pradhan,4 T. Tsendsuren,5 J.M. Foggin,6 C. Gaillard,7 D. Steane,8 I. Zakharov 9 and D.G. Bradley1 1. Department of Genetics, Trinity College, Dublin 2, Ireland 2. Department of Animal Science, Gansu Agricultural University, Lanzhou 730070, Gansu, P.R. China 3. Livestock Production Division, Department of Livestock Services, Harihar Bhawan, Pulchowk, Nepal 4. Resource Development Advisor, Nepal–Australia Community Resource Management Project, Kathmandu, Nepal 5. Institute of Biology, Academy of Sciences of Mongolia, Ulaan Baatar, Mongolia 6. Department of Biology, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287–1501 USA 7. Institute of Animal Breeding, University of Berne, Bremgarten-strasse 109a, CH-3012 Berne, Switzerland 8. FAO (Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations) Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific, 39 Phra Atit Road, Bangkok 10200, Thailand 9. Vavilov Institute of General Genetics Russian Academy of Sciences, Gubkin str., 3, 117809 GSP-1, Moscow B-333, Russia Summary Yak (Bos grunniens) are members of the Artiodactyla, family Bovidae, genus Bos. Wild yak are first observed at Pleistocene levels of the fossil record. We believed that they, together with the closely related species of Bos taurus, B. indicus and Bison bison, resulted from a rapid radiation of the genus towards the end of the Miocene. Today domestic yak live a fragile existence in a harsh environment. Their fitness for this environment is vital to their survival and to the millions of pastoralists who depend upon them. -

Kekexili Student Activity Booklet

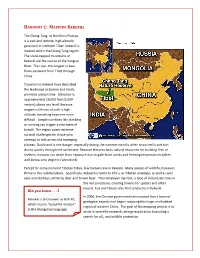

HANDOUT 1: MAPPING KEKEXILI The Chang Tang, or Northern Plateau, is a vast and remote, high altitude grassland in northern Tibet. Kekexili is located within the Chang Tang region. The snow‐capped mountains of Kekexili are the source of the Yangtze River. The river, the longest in Asia, flows eastward from Tibet through China. Travelers to Kekexili have described the landscape as barren and harsh, primitive and pristine. Elevation is approximately 16,000 feet (5,000 meters) above sea level. Because oxygen is thinner at such a high altitude, breathing becomes more difficult. Simple exertions like climbing or running can trigger a shortness of breath. The region poses extreme survival challenges for those who attempt to trek across the sweeping plateau. Quicksand is one danger, especially during the summer months when snow melts and rain drains quickly through the sandstone. Because the area lacks natural resources for building fires or shelters, humans risk death from exposure due to gale‐force winds and freezing temperatures (often well below zero degrees Fahrenheit). Except for some nomadic Tibetan tribes, few humans live in Kekexili. Many species of wildlife, however, thrive in this isolated place. Specifically, Kekexili is home to Chiru, or Tibetan antelope, as well as wild yaks and donkeys, white lip deer and brown bear. The Himalayan marmot, a type of rodent, burrows in the red sandstone, creating havens for spiders and other insects. Fox and falcons also find sanctuary in Kekexili. Did you know . .? In 2006, the Chinese government announced that a team of Kekexili is also known as Hoh Xil, geological experts had begun mapping this large uninhabited which means “beautiful maiden” region of western China. -

Summer Food Habits of Brown Bears in Kekexili Nature Reserve, Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau, China

Summer food habits of brown bears in Kekexili Nature Reserve, Qinghai–Tibetan plateau, China Xu Aichun1,2,5, Jiang Zhigang2,6, Li Chunwang2, Guo Jixun1,7, Wu Guosheng3, and Cai Ping4 1Key Laboratory of Vegetation Ecology, Ministry of Education, Northeast Normal University, Changchun, China 130024 2Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China 100080 3Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau Wildlife Rescue Center, Xining, China 810029 4Qinghai Province Wildlife and Nature Reserve Management Bureau, Xining, China 810029 Abstract: We documented food habits of brown bear (Ursus arctos) during summer 2005 in an important calving area for Tibetan antelope (Pantholops hodgsonii) in the Kekexili Nature Reserve, Qinghai province, China. Fecal analysis (n ¼ 83) revealed that the plateau pika (Ochotona curzoniae) was the primary prey (78% occurrence, 46% dry weight), and that wild yak (Bos grunniens;39%, 31%) and Tibetan antelope (35%, 17%) were important alternative prey. Vegetation also occurred in bear feces (17% occurrence). Brown bears in this region were evidently primarily carnivorous, a survival tactic adapted to the special environment of Qinghai–Tibetan plateau. Key words: Bos grunniens, brown bear, diet, Ochotona curzoniae, Pantholops hodgsonii, pika, scavenge, Tibetan antelope, Ursus arctos, wild yak Ursus 17(2):132–137 (2006) The brown bear (Ursus arctos) has a Holarctic growing season of vegetation, lack of protective cover, distribution that stretches from Eurasia to North and extremes in weather. They may be particularly America. With such a wide geographic distribution, vulnerable to changes in food availability because of the food habits of brown bears differ substantially in short time they have to acquire energy necessary for different geographic areas, and seasonal variation in maintenance, growth, and reproduction prior to winter food selection is common (Welch et al. -

The Yak Second Edition

THE YAK SECOND EDITION RAP publication 2003/06 RAP publication 2003/06 THE YAK SECOND EDITION REVISED AND ENLARGED By GERALD WIENER HAN JIANLIN LONG RUIJUN Published by the Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Bangkok, Thailand Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific Bangkok, Thailand This publication is produced by FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific Research funded by FAO Regional Project "Conservation and Use of Animal Genetic Resources in Asia and the Pacific" (GCP/RAS/144/JPN) The Government of Japan Jacket design and illustration and frontispiece by John Frisby, RIAS © FAO 2003 RAP Publication 2003/06 ISBN 92-5-104965-3 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific (RAP), Maliwan Mansion, 39 Phra Atit Road, Bangkok 10200 Thailand. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries For copies write to: The Animal Production Officer FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific 39 Phra Atit Road Bangkok 10200 Thailand Tel : +66 (0)2 697-4000 Fax : +66 (0)2 697 4445 Email: [email protected] ii THE YAK SECOND EDITION -o- FIRST EDITION CAI LI B.Sc. -

Ethnic and Cultural Diversity Amongst Yak Herding Communities in the Asian Highlands

sustainability Review Ethnic and Cultural Diversity amongst Yak Herding Communities in the Asian Highlands Srijana Joshi 1,* , Lily Shrestha 1, Neha Bisht 1, Ning Wu 2, Muhammad Ismail 1, Tashi Dorji 1, Gauri Dangol 1 and Ruijun Long 1,3,* 1 International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), G.P.O. Box 3226, Kathmandu 44700, Nepal; [email protected] (L.S.); [email protected] (N.B.); [email protected] (M.I.); [email protected] (T.D.); [email protected] (G.D.) 2 Chengdu Institute of Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), No.9 Section 4, Renmin Nan Road, Chengdu 610041, China; [email protected] 3 State Key Laboratory of Grassland and Agro-Ecosystems, International Centre for Tibetan Plateau Ecosystem Management, School of Life Sciences, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, Gansu, China * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.J.); [email protected] (R.L.) Received: 29 November 2019; Accepted: 18 January 2020; Published: 28 January 2020 Abstract: Yak (Bos grunniens L.) herding plays an important role in the domestic economy throughout much of the Asian highlands. Yak represents a major mammal species of the rangelands found across the Asian highlands from Russia and Kyrgyzstan in the west to the Hengduan Mountains of China in the east. Yak also has great cultural significance to the people of the Asian highlands and is closely interlinked to the traditions, cultures, and rituals of the herding communities. However, increasing issues like poverty, environmental degradation, and climate change have changed the traditional practices of pastoralism, isolating and fragmenting herders and the pastures they have been using for many years. -

List of Taxa for Which MIL Has Images

LIST OF 27 ORDERS, 163 FAMILIES, 887 GENERA, AND 2064 SPECIES IN MAMMAL IMAGES LIBRARY 31 JULY 2021 AFROSORICIDA (9 genera, 12 species) CHRYSOCHLORIDAE - golden moles 1. Amblysomus hottentotus - Hottentot Golden Mole 2. Chrysospalax villosus - Rough-haired Golden Mole 3. Eremitalpa granti - Grant’s Golden Mole TENRECIDAE - tenrecs 1. Echinops telfairi - Lesser Hedgehog Tenrec 2. Hemicentetes semispinosus - Lowland Streaked Tenrec 3. Microgale cf. longicaudata - Lesser Long-tailed Shrew Tenrec 4. Microgale cowani - Cowan’s Shrew Tenrec 5. Microgale mergulus - Web-footed Tenrec 6. Nesogale cf. talazaci - Talazac’s Shrew Tenrec 7. Nesogale dobsoni - Dobson’s Shrew Tenrec 8. Setifer setosus - Greater Hedgehog Tenrec 9. Tenrec ecaudatus - Tailless Tenrec ARTIODACTYLA (127 genera, 308 species) ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BALAENIDAE - bowheads and right whales 1. Balaena mysticetus – Bowhead Whale 2. Eubalaena australis - Southern Right Whale 3. Eubalaena glacialis – North Atlantic Right Whale 4. Eubalaena japonica - North Pacific Right Whale BALAENOPTERIDAE -rorqual whales 1. Balaenoptera acutorostrata – Common Minke Whale 2. Balaenoptera borealis - Sei Whale 3. Balaenoptera brydei – Bryde’s Whale 4. Balaenoptera musculus - Blue Whale 5. Balaenoptera physalus - Fin Whale 6. Balaenoptera ricei - Rice’s Whale 7. Eschrichtius robustus - Gray Whale 8. Megaptera novaeangliae - Humpback Whale BOVIDAE (54 genera) - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Addax nasomaculatus - Addax 2. Aepyceros melampus - Common Impala 3. Aepyceros petersi - Black-faced Impala 4. Alcelaphus caama - Red Hartebeest 5. Alcelaphus cokii - Kongoni (Coke’s Hartebeest) 6. Alcelaphus lelwel - Lelwel Hartebeest 7. Alcelaphus swaynei - Swayne’s Hartebeest 8. Ammelaphus australis - Southern Lesser Kudu 9. Ammelaphus imberbis - Northern Lesser Kudu 10. Ammodorcas clarkei - Dibatag 11. Ammotragus lervia - Aoudad (Barbary Sheep) 12. -

The Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972 ______

THE WILD LIFE (PROTECTION) ACT, 1972 ____________ ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS ____________ CHAPTER I PRELIMINARY SECTIONS 1. Short title, extent and commencement. 2. Definitions. CHAPTER II AUTHORITIES TO BE APPOINTED OR CONSTITUTES UNDER THE ACT 3. Appointment of Director and other officers. 4. Appointment of Life Warden and other officers. 5. Power to delegate. 5A. Constitution of the National Board for Wild Life. 5B. Standing Committee of the National Board. 5C. Functions of the National Board. 6. Constitution of State Board for Wild Life. 7. Procedure to be followed by the Board. 8. Duties of State Board for Wild Life. CHAPTER III HUNTING OF WILD ANIMALS 9. Prohibition of hunting. 10. [Omitted.] 11. Hunting of wild animals to be permitted in certain cases. 12. Grant of permit for special purposes. 13. [Omitted.] 14. [Omitted.] 15. [Omitted.] 16. [Omitted.] 17. [Omitted.] CHAPTER IIIA PROTECTION OF SPECIFIED PLANTS 17A. Prohibition of picking, uprooting, etc. of specified plant. 17B. Grants of permit for special purposes. 17C. Cultivation of specified plants without licence prohibited. 17D. Dealing in specified plants without licence prohibited. 17E. Declaration of stock. 17F. Possession, etc., of plants by licensee. 17G. Purchase, etc., of specified plants. 1 SECTIONS 17H. Plants to be Government property. CHAPTER IV PROTECTED AREAS Sanctuaries 18. Declaration of sanctuary. 18A. Protection to sanctuaries. 18B. Appointment of Collectors. 19. Collector to determine rights. 20. Bar of accrual of rights. 21. Proclamation by Collector. 22. Inquiry by Collector. 23. Powers of Collector. 24. Acquisition of rights. 25. Acquisition proceedings. 25A. Time-limit for completion of acquisition proceedings. 26. Delegation of Collector’s powers. -

The Endangered Mammals of Tibet

The Endangered Mammals of Tibet DIIR Publications Copyright March 2005, Environment and Development Desk, DIIR, CTA ISBN 81-86627-44-8 Environment and Development Desk Department of Information and International Relations Central Tibetan Administration Dharamshala - 176 215 H.P., India Tel: +91-1892-222457, 222510 Fax: +91-1892-224957 Email: [email protected], [email protected] & [email protected] Website: www.tibet.net Printed at Narthang Press, Dharamshala, H.P. FOREWORD The Environment and Development Desk is releasing an updated version of the book The Endangered Mammals of Tibet. This book contains description of mammals found in Tibet, whose existence on this planet is threatened or who are on the verge of extinction, as observed under the relevant international conventions and Chinese laws. The book provides background information about the habitat, behaviour, and threats to survival for each of these mammals. The discovery of the alarming and increasing trade in animal and animal parts in Asia, particularly in India and China, with Tibet being an important trade link between the supply and demand markets in these two countries, makes the release of this book timely and much needed. Environmental protection is now regarded as a priority in China, but China faces a huge uphill task in protecting the environment. This book is aimed at informing both Tibetan and non-Tibetan readers of the serious risks currently faced by wild animals, which have same rights as humans to live freely and in harmony with their surroundings on this planet. There have been a few isolated cases of Tibetans being involved in the international trade in animal and animal parts. -

Schedules I to VI of Wildlife Protection Act, 1972

SCHEDULE I (Sections 2, 8,9,11, 40,41, 48,51, 61 & 62) PART I MAMMALS [1. Andaman Wild pig (Sus sorofa andamanensis)] 2[1-A. Bharal (Ovisnahura)] 2[1 -B. Binturong (Arctictis Binturong)] 2. Black Buck (Antelope cervicapra) 2[2-A. •*•] 3. Brow-antlered Deer or Thamin (Cervus eldi) 3[3-A. Himalayan Brown bear (Ursus Arctos)] 3[3-B. Capped Langur (Presbytis pileatus)] 4. Caracal (Felis caracal) [4-A. Catecean specials] 5. Cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) 4[5-A. Chinese Pangolin (Mainis pentadactyla)] '[5-B. Chinkara or India Gazelle (Gazella gazella bennetti)] 6. Clouded Leopard (Neofelis nebulosa) 2[6-A. Crab-eating Macaque (Macaca irus umbrosa)] 2[6-B. Desert Cat (Felis libyca)] 3[6-C Desert fox (Vulpes bucapus)] 7. Dugong (Dugong dugon) 2[7-A Ermine (Mustele erminea)] 8. Fishing Cat (Felis viverrina) a[8-A Four-horned antelope (Tetraceros quadricomis)] 2[8-B. *••] 3[8-C ***] 3[8-D. Gangetic dolphin (Platanista gangetica)] 3[8-E. Gaur or Indian bison (Bos gaurus)] 9. Golden Cat (Felis temmincki) 10. Golden Langur (Presbytis geei) 3[10-A. Giant squirrel (Ratufa macroura)] [10-B. Himalayan Ibex (Capra ibex)] ' [10-C. Himalayan Tahr (Hemitragus jemlahicus)] 11. Hispid Hare (Caprolagus hispidus) 3[11-A. Hog badgar (Arconyx collaris)] 12. Hoolock (Hyloba tes hoolock) 1 Vide Notification No. FJ11012/31/76 FRY(WL), dt. 5-10-1977. 2 Vide Notification No. Fl-28/78 FRY(WL), dt. 9-9-1980. 3 Vide Notification No. S.O. 859(E), dt. 24-11-1986. 4 Vide Notification No. F] 11012/31 FRY(WL), dt.