Wild Yak Bos Mutus in Nepal: Rediscovery of a Flagship Species

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pro-Poor Tourism Case Study from Humla District, West

48 6. Appendices 6.1 Data on tourist numbers in Humla Table A1 Number of trekking permits issued16 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 28 209 191 462 404 558 949 595 Table A2 Nationality of tourists registering at Simikot Police Station 1996-2000 (top ten nationalities account for 97% of visitors ) % of total tourists SN Country over 4 years 1 Germany 27.13 2 Australia/Austria 13.65 3 Switzerland 11.61 4 USA 11.45 5 France 9.36 6 UK 7.76 7 Italy 5.12 8 Spain 2.64 9 Netherlands 2.20 10 Japan 1.65 16 Source: Paudyal & Sharma 2000 49 6.2 Background information on SNV’s programmes in Humla preceding the DPP sustainable tourism programme 1985-1992 A Trail and Bridge Building Project was run to improve infrastructure in the Karnali Zone because this was seen to be a pre-requisite for developing the area generally. The project completed a total of 21 bridges, 2 trails and 10 drinking water schemes covering several Karnali Zone districts. In Humla, work on trails, 7 bridges, and several drinking water projects were completed. On the Simikot - Hilsa trail a suspension bridge crossing the Karnali River at Yalbang and a section of trail called ‘Salli-Salla’ were constructed. 1993 – September 1999 The Karnali Local Development Programme was run to further develop infrastructural improvements and to integrate these with social development by building capacity at community and local NGO levels. The district level activities included • District Development Committee (DDC) (i.e. local government) capacity building in participatory planning; • Improvement of intra-district infrastructure; and • Support of NGOs committed to work in the Karnali Zone. -

Feasibility Study of Kailash Sacred Landscape

Kailash Sacred Landscape Conservation Initiative Feasability Assessment Report - Nepal Central Department of Botany Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, Nepal June 2010 Contributors, Advisors, Consultants Core group contributors • Chaudhary, Ram P., Professor, Central Department of Botany, Tribhuvan University; National Coordinator, KSLCI-Nepal • Shrestha, Krishna K., Head, Central Department of Botany • Jha, Pramod K., Professor, Central Department of Botany • Bhatta, Kuber P., Consultant, Kailash Sacred Landscape Project, Nepal Contributors • Acharya, M., Department of Forest, Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation (MFSC) • Bajracharya, B., International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) • Basnet, G., Independent Consultant, Environmental Anthropologist • Basnet, T., Tribhuvan University • Belbase, N., Legal expert • Bhatta, S., Department of National Park and Wildlife Conservation • Bhusal, Y. R. Secretary, Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Das, A. N., Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Ghimire, S. K., Tribhuvan University • Joshi, S. P., Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Khanal, S., Independent Contributor • Maharjan, R., Department of Forest • Paudel, K. C., Department of Plant Resources • Rajbhandari, K.R., Expert, Plant Biodiversity • Rimal, S., Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Sah, R.N., Department of Forest • Sharma, K., Department of Hydrology • Shrestha, S. M., Department of Forest • Siwakoti, M., Tribhuvan University • Upadhyaya, M.P., National Agricultural Research Council -

Phylogeographical Analyses of Domestic and Wild Yaks

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital.CSIC RIGIN AL Phylogeographical analyses of domestic AR TI C L E and wild yaks based on mitochondrial DNA: new data and reappraisal Zhaofeng Wang1†, Xin Shen2†, Bin Liu2†, Jianping Su3†, Takahiro Yonezawa4, Yun Yu2, Songchang Guo3, Simon Y. W. Ho5, Carles Vila` 6, Masami Hasegawa4 and Jianquan Liu1* 1Molecular Ecology Group, Key Laboratory of AB STRACT Arid and Grassland Ecology, School of Life Science, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, Aim We aimed to examine the phylogeographical structure and demographic 2 history of domestic and wild yaks ( ) based on a wide range of Gansu, China, Beijing Genomics Institute, Bos grunniens Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 101300, samples and complete mitochondrial genomic sequences. 3 China, Key Laboratory of Evolution and Location The Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau (QTP) of western China. Adaptation of Plateau Biota, Northwest Plateau Institute of Biology, Chinese Academy Methods All available D-loop sequences for 405 domesticated yaks and 47 wild of Sciences, Xining 810001, Qinghai, China, yaks were examined, including new sequences from 96 domestic and 34 wild yaks. 4School of Life Sciences, Fudan University, We further sequenced the complete mitochondrial genomes of 48 domesticated Shanghai 200433, China, 5Centre for and 21 wild yaks. Phylogeographical analyses were performed using the Macroevolution and Macroecology, Research mitochondrial D-loop and the total genome datasets. School of Biology, Australian National Results We recovered a total of 123 haplotypes based on the D-loop sequences University, Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia, in wild and domestic yaks. -

Structural Characterisation of Toll-Like Receptor 1 (TLR1) and Toll-Like

RVC OPEN ACCESS REPOSITORY – COPYRIGHT NOTICE This is the peer-reviewed, manuscript version of the following article: Woodman, S., Gibson, A. J., García, A. R., Contreras, G. S., Rossen, J. W., Werling, D. and Offord, V. (2016) 'Structural characterisation of Toll-like receptor 1 (TLR1) and Toll-like receptor 6 (TLR6) in elephant and harbor seals', Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology, 169, 10-14. The final version is available online via http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetimm.2015.11.006. © 2016. This manuscript version is made available under the CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The full details of the published version of the article are as follows: TITLE: Structural characterisation of Toll-like receptor 1 (TLR1) and Toll-like receptor 6 (TLR6) in elephant and harbor seals AUTHORS: Woodman, S., Gibson, A. J., García, A. R., Contreras, G. S., Rossen, J. W., Werling, D. and Offord, V. JOURNAL TITLE: Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology VOLUME: 169 PUBLISHER: Elsevier PUBLICATION DATE: January 2016 DOI: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2015.11.006 1 Structural characterisation of Toll-like receptor 1 (TLR1) and Toll-like receptor 6 (TLR6) in 2 elephant and harbor seals 3 4 Sally Woodman1,Amanda J. Gibson1, Ana Rubio García2, Guillermo Sanchez Contreras2, John W. 5 Rossen3, Dirk Werling1, Victoria Offord1,* 6 7 1Molecular Immunology Group, Department of Pathology and Pathogen Biology, Royal Veterinary 8 College, Hawkshead Lane, Hatfield, AL9 7TA, UK; 9 2Veterinary Department, Seal Rehabilitation and Research Centre (SRRC), Pieterburen, The 10 Netherlands; 11 3Department of Medical Microbiology, University of Groningen, University Medical Center 12 Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands; 13 * Corresponding author at the Research Support Office, Royal Veterinary College, Hawkshead Lane, 14 Hatfield, AL9 7TA, UK Tel: ++44 1707 667038; E-Mail: [email protected] 15 16 1 1 Abstract 2 Pinnipeds are a diverse clade of semi-aquatic mammals, which act as key indicators of ecosystem health. -

Genetic Variation of Mitochondrial DNA Within Domestic Yak Populations J.F

Genetic variation of mitochondrial DNA within domestic yak populations J.F. Bailey,1 B. Healy,1 H. Jianlin,2 L. Sherchand,3 S.L. Pradhan,4 T. Tsendsuren,5 J.M. Foggin,6 C. Gaillard,7 D. Steane,8 I. Zakharov 9 and D.G. Bradley1 1. Department of Genetics, Trinity College, Dublin 2, Ireland 2. Department of Animal Science, Gansu Agricultural University, Lanzhou 730070, Gansu, P.R. China 3. Livestock Production Division, Department of Livestock Services, Harihar Bhawan, Pulchowk, Nepal 4. Resource Development Advisor, Nepal–Australia Community Resource Management Project, Kathmandu, Nepal 5. Institute of Biology, Academy of Sciences of Mongolia, Ulaan Baatar, Mongolia 6. Department of Biology, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287–1501 USA 7. Institute of Animal Breeding, University of Berne, Bremgarten-strasse 109a, CH-3012 Berne, Switzerland 8. FAO (Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations) Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific, 39 Phra Atit Road, Bangkok 10200, Thailand 9. Vavilov Institute of General Genetics Russian Academy of Sciences, Gubkin str., 3, 117809 GSP-1, Moscow B-333, Russia Summary Yak (Bos grunniens) are members of the Artiodactyla, family Bovidae, genus Bos. Wild yak are first observed at Pleistocene levels of the fossil record. We believed that they, together with the closely related species of Bos taurus, B. indicus and Bison bison, resulted from a rapid radiation of the genus towards the end of the Miocene. Today domestic yak live a fragile existence in a harsh environment. Their fitness for this environment is vital to their survival and to the millions of pastoralists who depend upon them. -

SNV in Humla District, West Nepal

PPT Working Paper No. 3 Practical strategies for pro-poor tourism: case study of pro-poor tourism and SNV in Humla District, West Nepal Naomi M. Saville April 2001 Preface This case study was written as a contribution to a project on ‘pro-poor tourism strategies.’ The pro-poor tourism project is collaborative research involving the Overseas Development Institute (ODI), the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), the Centre for Responsible Tourism at the University of Greenwich (CRT), together with in-country case study collaborators. It is funded by the Economic and Social Research Unit (ESCOR) of the UK Department for International Development (DFID). The project reviewed the experience of pro-poor tourism strategies based on six commissioned case studies. These studies used a common methodology developed within this project. The case study work was undertaken mainly between September and December 2000. Findings have been synthesised into a research report and a policy briefing, while the 6 case studies are all available as Working Papers. The outputs of the project are: Pro-poor tourism strategies: Making tourism work for the poor. Pro-poor Tourism Report No 1. (60pp) by Caroline Ashley, Dilys Roe and Harold Goodwin, April 2001. Pro-poor tourism: Expanding opportunities for the poor. PPT Policy Briefing No 1. (4pp). By Caroline Ashley, Harold Goodwin and Dilys Roe, April 2001. Pro poor Tourism Working Papers: No 1 Practical strategies for pro-poor tourism, Wilderness Safaris South Africa: Rocktail Bay and Ndumu Lodge. Clive Poultney and Anna Spenceley No 2 Practical strategies for pro-poor tourism. Case studies of Makuleke and Manyeleti tourism initiatives: South Africa. -

Kekexili Student Activity Booklet

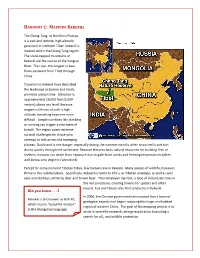

HANDOUT 1: MAPPING KEKEXILI The Chang Tang, or Northern Plateau, is a vast and remote, high altitude grassland in northern Tibet. Kekexili is located within the Chang Tang region. The snow‐capped mountains of Kekexili are the source of the Yangtze River. The river, the longest in Asia, flows eastward from Tibet through China. Travelers to Kekexili have described the landscape as barren and harsh, primitive and pristine. Elevation is approximately 16,000 feet (5,000 meters) above sea level. Because oxygen is thinner at such a high altitude, breathing becomes more difficult. Simple exertions like climbing or running can trigger a shortness of breath. The region poses extreme survival challenges for those who attempt to trek across the sweeping plateau. Quicksand is one danger, especially during the summer months when snow melts and rain drains quickly through the sandstone. Because the area lacks natural resources for building fires or shelters, humans risk death from exposure due to gale‐force winds and freezing temperatures (often well below zero degrees Fahrenheit). Except for some nomadic Tibetan tribes, few humans live in Kekexili. Many species of wildlife, however, thrive in this isolated place. Specifically, Kekexili is home to Chiru, or Tibetan antelope, as well as wild yaks and donkeys, white lip deer and brown bear. The Himalayan marmot, a type of rodent, burrows in the red sandstone, creating havens for spiders and other insects. Fox and falcons also find sanctuary in Kekexili. Did you know . .? In 2006, the Chinese government announced that a team of Kekexili is also known as Hoh Xil, geological experts had begun mapping this large uninhabited which means “beautiful maiden” region of western China. -

Beekeeping in Humla District West Nepal

Beekeeping in Humla district West Nepal: a field study Commissioned by the District Partner Programme (DPP) - SNV Nepal With extra results from a study commissioned by ApTibeT Conducted and written by Naomi M. Saville and Narayan Prasad Acharya Final Draft submitted 15 May 2001 1 Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the District Partner Programme (DPP) of SNV for commissioning and funding this study and Appropriate Technology for Tibetans (ApTibeT) for allowing us to share our findings from the study commissioned by them. Thanks to all the field staff of DPP in Humla who welcomed us and made us so much at home in their guesthouse. An especial 'thank you' to Tschering Dorje who guided us, carried our pack and helped us in every way in the field. We could not have hoped for a more cooperative and easy assistant. Thanks to staff of the Village Development Programme (VDP), especially Phunjok Lama and Ram Chandra Jaisi, who assisted us in the field. A very big 'thank you' to the staff of Humla Conservation and Development Association (HCDA) for their excellent management and exceedingly warm welcome in the field. Thanks especially to HCDA field motivators Sunita Budha, Hira Rokaya, Dharma Bahadur Shahi and Prayag Bahadur Shahi for their enthusiastic assistance in working with Melchham communities and in making us welcome and comfortable. Thanks to HCDA runner Kara Siraha for assistance and Sunam Budha and Gorkha Budha for accompanying and guiding us over Margole Lekh. Thanks also to Sonam Lama of Bargaun for guide-porter assistance and Khadka Chatyel who guided us over Muniya Lekh in April 2000 during the ApTibeT study. -

Summer Food Habits of Brown Bears in Kekexili Nature Reserve, Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau, China

Summer food habits of brown bears in Kekexili Nature Reserve, Qinghai–Tibetan plateau, China Xu Aichun1,2,5, Jiang Zhigang2,6, Li Chunwang2, Guo Jixun1,7, Wu Guosheng3, and Cai Ping4 1Key Laboratory of Vegetation Ecology, Ministry of Education, Northeast Normal University, Changchun, China 130024 2Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China 100080 3Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau Wildlife Rescue Center, Xining, China 810029 4Qinghai Province Wildlife and Nature Reserve Management Bureau, Xining, China 810029 Abstract: We documented food habits of brown bear (Ursus arctos) during summer 2005 in an important calving area for Tibetan antelope (Pantholops hodgsonii) in the Kekexili Nature Reserve, Qinghai province, China. Fecal analysis (n ¼ 83) revealed that the plateau pika (Ochotona curzoniae) was the primary prey (78% occurrence, 46% dry weight), and that wild yak (Bos grunniens;39%, 31%) and Tibetan antelope (35%, 17%) were important alternative prey. Vegetation also occurred in bear feces (17% occurrence). Brown bears in this region were evidently primarily carnivorous, a survival tactic adapted to the special environment of Qinghai–Tibetan plateau. Key words: Bos grunniens, brown bear, diet, Ochotona curzoniae, Pantholops hodgsonii, pika, scavenge, Tibetan antelope, Ursus arctos, wild yak Ursus 17(2):132–137 (2006) The brown bear (Ursus arctos) has a Holarctic growing season of vegetation, lack of protective cover, distribution that stretches from Eurasia to North and extremes in weather. They may be particularly America. With such a wide geographic distribution, vulnerable to changes in food availability because of the food habits of brown bears differ substantially in short time they have to acquire energy necessary for different geographic areas, and seasonal variation in maintenance, growth, and reproduction prior to winter food selection is common (Welch et al. -

The Yak Second Edition

THE YAK SECOND EDITION RAP publication 2003/06 RAP publication 2003/06 THE YAK SECOND EDITION REVISED AND ENLARGED By GERALD WIENER HAN JIANLIN LONG RUIJUN Published by the Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Bangkok, Thailand Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific Bangkok, Thailand This publication is produced by FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific Research funded by FAO Regional Project "Conservation and Use of Animal Genetic Resources in Asia and the Pacific" (GCP/RAS/144/JPN) The Government of Japan Jacket design and illustration and frontispiece by John Frisby, RIAS © FAO 2003 RAP Publication 2003/06 ISBN 92-5-104965-3 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific (RAP), Maliwan Mansion, 39 Phra Atit Road, Bangkok 10200 Thailand. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries For copies write to: The Animal Production Officer FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific 39 Phra Atit Road Bangkok 10200 Thailand Tel : +66 (0)2 697-4000 Fax : +66 (0)2 697 4445 Email: [email protected] ii THE YAK SECOND EDITION -o- FIRST EDITION CAI LI B.Sc. -

Ethnic and Cultural Diversity Amongst Yak Herding Communities in the Asian Highlands

sustainability Review Ethnic and Cultural Diversity amongst Yak Herding Communities in the Asian Highlands Srijana Joshi 1,* , Lily Shrestha 1, Neha Bisht 1, Ning Wu 2, Muhammad Ismail 1, Tashi Dorji 1, Gauri Dangol 1 and Ruijun Long 1,3,* 1 International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), G.P.O. Box 3226, Kathmandu 44700, Nepal; [email protected] (L.S.); [email protected] (N.B.); [email protected] (M.I.); [email protected] (T.D.); [email protected] (G.D.) 2 Chengdu Institute of Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), No.9 Section 4, Renmin Nan Road, Chengdu 610041, China; [email protected] 3 State Key Laboratory of Grassland and Agro-Ecosystems, International Centre for Tibetan Plateau Ecosystem Management, School of Life Sciences, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, Gansu, China * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.J.); [email protected] (R.L.) Received: 29 November 2019; Accepted: 18 January 2020; Published: 28 January 2020 Abstract: Yak (Bos grunniens L.) herding plays an important role in the domestic economy throughout much of the Asian highlands. Yak represents a major mammal species of the rangelands found across the Asian highlands from Russia and Kyrgyzstan in the west to the Hengduan Mountains of China in the east. Yak also has great cultural significance to the people of the Asian highlands and is closely interlinked to the traditions, cultures, and rituals of the herding communities. However, increasing issues like poverty, environmental degradation, and climate change have changed the traditional practices of pastoralism, isolating and fragmenting herders and the pastures they have been using for many years. -

List of Taxa for Which MIL Has Images

LIST OF 27 ORDERS, 163 FAMILIES, 887 GENERA, AND 2064 SPECIES IN MAMMAL IMAGES LIBRARY 31 JULY 2021 AFROSORICIDA (9 genera, 12 species) CHRYSOCHLORIDAE - golden moles 1. Amblysomus hottentotus - Hottentot Golden Mole 2. Chrysospalax villosus - Rough-haired Golden Mole 3. Eremitalpa granti - Grant’s Golden Mole TENRECIDAE - tenrecs 1. Echinops telfairi - Lesser Hedgehog Tenrec 2. Hemicentetes semispinosus - Lowland Streaked Tenrec 3. Microgale cf. longicaudata - Lesser Long-tailed Shrew Tenrec 4. Microgale cowani - Cowan’s Shrew Tenrec 5. Microgale mergulus - Web-footed Tenrec 6. Nesogale cf. talazaci - Talazac’s Shrew Tenrec 7. Nesogale dobsoni - Dobson’s Shrew Tenrec 8. Setifer setosus - Greater Hedgehog Tenrec 9. Tenrec ecaudatus - Tailless Tenrec ARTIODACTYLA (127 genera, 308 species) ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BALAENIDAE - bowheads and right whales 1. Balaena mysticetus – Bowhead Whale 2. Eubalaena australis - Southern Right Whale 3. Eubalaena glacialis – North Atlantic Right Whale 4. Eubalaena japonica - North Pacific Right Whale BALAENOPTERIDAE -rorqual whales 1. Balaenoptera acutorostrata – Common Minke Whale 2. Balaenoptera borealis - Sei Whale 3. Balaenoptera brydei – Bryde’s Whale 4. Balaenoptera musculus - Blue Whale 5. Balaenoptera physalus - Fin Whale 6. Balaenoptera ricei - Rice’s Whale 7. Eschrichtius robustus - Gray Whale 8. Megaptera novaeangliae - Humpback Whale BOVIDAE (54 genera) - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Addax nasomaculatus - Addax 2. Aepyceros melampus - Common Impala 3. Aepyceros petersi - Black-faced Impala 4. Alcelaphus caama - Red Hartebeest 5. Alcelaphus cokii - Kongoni (Coke’s Hartebeest) 6. Alcelaphus lelwel - Lelwel Hartebeest 7. Alcelaphus swaynei - Swayne’s Hartebeest 8. Ammelaphus australis - Southern Lesser Kudu 9. Ammelaphus imberbis - Northern Lesser Kudu 10. Ammodorcas clarkei - Dibatag 11. Ammotragus lervia - Aoudad (Barbary Sheep) 12.