History of the English Concept of Poetic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Creativity and Originality in Verse Discourses

On Creativity and Originalityin Ve rse Discourses MILOSAV Ż. ĆARKIĆ (Belgrade) O.O. In verse discourses, as probably in2 no others, there is a large number of ste reotypes 1 ( canons, conventions, norms ) impo sed by a specific period of time, a specific genre, a specific literary movement (school), specific literature, the struc- The concept of stereotype. which is defined asa tri te. banał, fixed expression or act. is most often felt as if conveying a negative connotalion, and directly associa1ed with cliche (routine s1ylistic and structural ac1s which have łosi their anistic significance and expressiveness. but are stili used like a mechanical pattern: in linguis1ics, cliches include: idioms. all ossified phrases, sayings, proverbs (Petkovic 1995: 95) and platitudes (unchangeable, ready-made pauems which many ad here to blindly, a 1rite. banał phrase or such a way ofthinking and expression). Contrary Io such at titudes, there are other opinions a1 least as regards the scholarly style (Kouorova 1 998). 1t is 1he refore thai in this case, especially regarding literary-artis1ic style, the concept of stereotype conveys posi1ive conno1ations and is to a cenain extent equa1ed with canon (as a se1 of aesthetic rules, pauerns dominating poetic s1ructures). convention (deriving from the long-standing tradi tion of a melhod of literary creation offering its expressive potentials even to la1er anisls) and norm (as a prese1 rule or a set of rules commining the anis1 10 cenain li1erary methods. but not re s1raining poetic personali ty development. since a poe1ic work emerges either in compliance with a norm or in depanure from it. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles a Statistical Analysis of The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles A Statistical Analysis of the Metrics of the Classic French Decasyllable and Classic Alexandrine A dissertation submitted in partial satistfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Romance Linguistics and Literature by Henry Parkman Biggs 1996 TABLE OF CONTENTS 0. Introduction....................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 Metrics ..........................................................................................................3 1.2 French Metrics...............................................................................................8 1.2.2 The Classic French Decasyllable...................................................................10 1.2.2.1 Syllable Count................................................................................................10 1.2.2.2 Stress Requirements.......................................................................................12 1.2.2.3 The Caesura...................................................................................................14 1.2.2.4 Proposed Bans on Hemistich-Penultimate Stress ..........................................16 1.2.3 The Classic French Alexandrine....................................................................18 1.2.4 Generative French Metrics.............................................................................21 1.3 French Prosodic Phonology...........................................................................23 -

Tesi Di Laurea

Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Scienze del Linguaggio D.M. 270/2004 Tesi di Laurea The Contribution of Germanic Sources in the Textual Reconstruction of the Chanson de Roland Relatrice Prof.ssa Marina Buzzoni Correlatore Prof. Marco Infurna Laureando Lorenzo Trevisan Matricola 860930 Anno Accademico 2018 / 2019 The importance of the Germanic sources in the Chanson de Roland 2 Introduction Index Introduction ................................................................................................ 7 Foreword .................................................................................................... 11 I. Literary context and poetic tradition ............................................... 13 1. Europe in the High Medieval Period ........................................... 13 1.1 Feudalism and rural aristocracy ........................................ 14 1.2 Secular powers and the Church ........................................... 17 1.3 Expanding the borders of Christendom .............................. 19 1.4 Trade, technology and towns ............................................... 21 1.5 Knowledge and culture ....................................................... 23 2. The rise of vernacular literature in Romance .............................. 25 2.1 The Carolingian Renaissance ............................................. 25 2.2 The first Old French texts .................................................... 26 2.3 The Hagiographic Poems .................................................... 28 3. The Old French Epic ................................................................... -

Chaucer's Invention of the Iambic Pentameter Author(S): Martin J

"The Craft so Long to Lerne": Chaucer's Invention of the Iambic Pentameter Author(s): Martin J. Duffell Source: The Chaucer Review, Vol. 34, No. 3 (2000), pp. 269-288 Published by: Penn State University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25096094 Accessed: 25-08-2015 18:58 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Penn State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Chaucer Review. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 136.167.36.226 on Tue, 25 Aug 2015 18:58:16 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions "THE CRAFT SO LONG TO LERNE": CHAUCER'S INVENTION OF THE IAMBICPENTAMETER byMartin J. Duffell In recent two branches of and statistical years mathematics, computation analysis, have helped settle some bitter and long-running disputes in the area of Chaucer's metrics. First a statistical Gasparov developed technique, probability modelling, that compared accentual configurations in verse with those found in prose, and thereby established that the Italian endecasill abo should be classified as intermediate between syllabic and stress-syllabic.1 so Since Chaucer borrowed much from Boccaccio, this clearly has impli on cations the typology of the English poet's long-line metre. -

FRENCH VERSIFICATION: Z Lbid,, Pp

MAI,COI,M BOWIE N OTES APPENDIX | (Eturcs co,Hl)lètes (Paris, r945), pp.666-79 ancl 68o-6. FRENCH VERSIFICATION: z lbid,, pp. 666-7, A SUMMARY 1 lbid., p. 67r. 4 lbid., p. 67L. 5 G.W.F. I{egel, "fhe Phenomenology of Spirit, traus. A, V. Miller Cliue Scott (Oxforcl, r977), p. z4r, (All examples ir this appendix are clrawn fr.rn rinereenth-century verse and, rvhenever possible, frorn the poeurs anaryseci in the body of ,rr.î.,"k1. The regular alexandrine Ainsi,/toujours poussés//vers de nouveaux/rivagcs, z+ 4+ 4-l z Dans la nuit/éternelle//ernportés/sans retour, 3+1+1+3 Ne pourrons-nous/jamais//sur I'océan/cles âges 4+2+4+z Jeter I'tncre/un seul jour? 3'F 3 The sta'z¿rs of Lamartine's'r-e [.ac'are each courp'secl of three alexan- clrines followecl by a hexasyllable, i.e. \ z, r z, r z, 6. ihe scansion of the 6rsr stanza irrrmecliately rnakes several things clcar about the regular rrlcx- ancirine: It has a r fixed meclial caesurâ (marked //) after the sixth syllable, r.vhich enforces an accenr (stress) rn the sixth syllable. The only uth", oblligntu,y accent in the lirre falls on the final (rwelfth) syllable. z Tlre caesurit is a metrical j'ncrure rvhich us'ally c.ircicles lvith a signifìcant syntactical juncture (a'd rhus a pause), f<¡r reasons which wilr beco.re appa'enr. ßut it is fìrsr and forenrtxt the rine's principal pciinr of rhythuric articulation, not its rnosr obtrusive synractic break. -

A History of French Literature from Chanson De Geste to Cinema

A History of French Literature From Chanson de geste to Cinema DAVID COWARD HH A History of French Literature For Olive A History of French Literature From Chanson de geste to Cinema DAVID COWARD © 2002, 2004 by David Coward 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of David Coward to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published 2002 First published in paperback 2004 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Coward, David. A history of French literature / David Coward. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–631–16758–7 (hardback); ISBN 1–4051–1736–2 (paperback) 1. French literature—History and criticism. I. Title. PQ103.C67 2002 840.9—dc21 2001004353 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. 1 Set in 10/13 /2pt Meridian by Graphicraft Ltd, Hong Kong Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by TJ International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall For further information on Blackwell Publishing, visit our website: http://www.blackwellpublishing.com Contents -

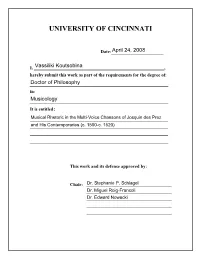

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Musical Rhetoric in the Multi-Voice Chansons of Josquin des Prez and His Contemporaries (c. 1500-c. 1520) A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Division of Composition, Musicology and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music By VASSILIKI KOUTSOBINA B.S., Chemistry University of Athens, Greece, April 1989 M.M., Music History and Literature The Hartt School, University of Hartford, Connecticut, May 1994 Committee Chair: Dr. Stephanie P. Schlagel 2008 ABSTRACT The first quarter of the sixteenth century witnessed tightening connections between rhetoric, poetry, and music. In theoretical writings, composers of this period are evaluated according to their ability to reflect successfully the emotions and meaning of the text set in musical terms. The same period also witnessed the rise of the five- and six-voice chanson, whose most important exponents are Josquin des Prez, Pierre de La Rue, and Jean Mouton. The new expanded textures posed several compositional challenges but also offered greater opportunities for text expression. Rhetorical analysis is particularly suitable for this repertory as it is justified by the composers’ contacts with humanistic ideals and the newer text-expressive approach. Especially Josquin’s exposure to humanism must have been extensive during his long-lasting residence in Italy, before returning to Northern France, where he most likely composed his multi- voice chansons. -

The Ikpluewce Op Paul Verlaine and Other French Poets

THE IKPLUEWCE OP PAUL VERLAINE AND OTHER FRENCH POETS OF THE SECOND HALF OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY ON MANUEL MACHADO GILLIAN MARGARET GAYTON B.A. Newnham College, Cambridge University, 1963 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFID.'JENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Hispanic and Italian Studies We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standards THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBTA September, 1973 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada i ABSTRACT The extent to which the poetry of Manuel Machado was influenced by that of Verlaine has been noted by many critics since the publication of Alma in 1901, and it is generally agreed that the two years Machado spent in Paris prior to the publication of that collection were responsible for French elements in his work. Nevertheless, no close textual examination of Machado*s poetry for direct Verlainian influence had been made until now, possibly because his contemporary Darfo is frequently considered to have been the first to introduce Verlaine*s themes and techniques into Spanish verse. -

Shame in the Fabliaux Scott Rb Own

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Foreign Languages & Literatures ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 9-12-2014 Shame in the Fabliaux Scott rB own Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/fll_etds Recommended Citation Brown, Scott. S" hame in the Fabliaux." (2014). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/fll_etds/81 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Foreign Languages & Literatures ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Scott Brown Candidate Foreign Languages and Literatures Department This thesis is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Thesis Committee: Pamela Cheek, Chairperson Marina Peters-Newell Stephen Bishop ii SHAME IN THE FABLIAUX by SCOTT S. BROWN BACHELOR OF ARTS FRENCH AND ENGLISH THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts French The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico July 2014 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to hereby recognize all of the professors, friends, family members, editors and my partner who have helped bring this work to fruition. I especially thank my committee of studies who were able to guide me through the process. Thank you Pamela Cheek, Marina Peters-Newell and Stephen Bishop. I also thank Ashley for her encouragement and edits. iv SHAME IN THE FABLIAUX by Scott S. Brown B.A., French and English, University of Arkansas, 2008 M.A., French, University of New Mexico, 2014 ABSTRACT In this thesis I highlight the literary techniques used in fabliaux to understand the power struggles traversed by the characters. -

Alphabetical List of Entries

Alphabetical List of Entries accent confessional poetry heroic couplet accentual- syllabic verse consonance heroic verse accentual verse convention hexameter air couplet hiatus alba cross rhyme homoeoteleuton alexandrine dactyl hymn alliteration decasyllable hyperbaton ambiguity decorum hyperbole anacoluthon deixis hypotaxis and parataxis anacreontic demotion iambic anadiplosis devotional poetry idyll analogy. See METAPHOR; dialogue image SIMILE; SYMBOL diction imagery anapest dimeter indeterminacy anaphora dozens In Memoriam stanza antistrophe dramatic monologue. See internal rhyme antithesis MONOLOGUE invective antonomasia dramatic poetry irony aporia dream vision isocolon and parison apostrophe eclogue kenning assonance ekphrasis lament asyndeton elegiac distich leonine rhyme, verse audience. See PERFORMANCE elegiac stanza letter, verse. See VERSE EPISTLE ballad elegy limerick ballad meter, hymn meter elision line beat ellipsis litotes Biblical poetry. See HYMN; encomium love poetry PSALM English prosody lyric blank verse enjambment lyric sequence blason envoi madrigal blues epic masculine and feminine broken rhyme epigram metaphor burlesque. See PARODY epitaph meter caesura epithalamium metonymy canon epithet mimesis carpe diem epode mock epic, mock heroic catachresis euphony monologue catalexis eye rhyme narrative poetry catalog fabliau narrator. See PERSONA; VOICE chain rhyme foot (modern) near rhyme chiasmus form nonsense verse Christabel meter fourteener octave closure free verse octosyllable colon genre ode complaint georgic onomatopoeia -

Free Verse and the Constraints of Metre in English Poetry

FACULTY OF HUMANITIE S UNIVERSITY OF COPENH AGEN PhD thesis Jesper Kruse Free Verse and the Constraints of Metre in English Poetry Name of department: Department of English, Germanic and Romance Studies Author: Jesper Kruse Title: Free Verse and the Constraints of Metre in English Poetry Supervisor: Professor Charles Lock Submitted: 31 January 2012 Acknowledgements The faults of this study would have been greater than they are and its merits smaller without the kindness and help from a large number of friends and colleagues. I wish to thank: Jonas Holm Aagaard, Dorte Albrechtsen, Susan Ang, Søren Staal Balslev, Martyn Bone, Clare Brant, Dorrit Einersen, Anastasia Gremm, Greg Hewett, Adam Hyllested, Annemarie Jensen, Line B. Kristensen, Josephine Lehaff, Arianna Maiorani, Winfried Menninghaus, Andrew Miller, Jens Erik Mogensen, Jimmi Nielsen, Toke Nordbo, Dennis Omø, Rajeev S. Patke, Siff Pors, Robert Rix, Ruben Schachtenhaufen, Karsten Schou, Steen Schousboe, Inge Birgitte Siegumfeldt, Annelise Siversen, Jørgen Staun, Anna Wegener and Elzbieta Jolanta Wójcik-Leese. I am particularly indebted to Henrik Gottlieb, Jessica Ortner and Bill Overton for their generosity and hospitality. Furthermore, for their enduring patience and encouragement, I am grateful to my parents as well as to my friends, Christel and Lars. Most of all, however, I am grateful to Cindy for, well, everything: this dissertation is dedicated to her. Finally, I wish to thank my supervisor, Professor Charles Lock, who also supervised my BA on exclamation marks in English verse and my MA on the relationship between phonotactics and metre. Both of these projects owed their conception to an informal reading group headed by Charles Lock, and of which I was fortunate enough to be a member. -

The Christianisation of Latin Metre a Study of Bede’S De Arte Metrica

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto Seppo Heikkinen The Christianisation of Latin Metre A Study of Bede’s De arte metrica Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in auditorium M1, on the 21st of March, 2012, at 12 o’clock. ISBN 978-952-10-7808-8 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-10-7807-1 (PDF) Unigrafia Helsinki 2012 Contents 1. Introduction 1 1.1. General observations 1 1.2. Grammar and metre in Anglo-Saxon England 2 1.3. The dating of Bede’s De arte metrica 5 1.4. The role of metrics in Bede’s curriculum 9 1.5. The structure and aims of De arte metrica 11 1.6. Bede’s Christian agenda and its implementation in his discussion of metrics 13 2. Hexameter verse and general prosody 17 2.1. The dactylic hexameter in Anglo-Saxon England 17 2.2. Classical and post-classical prosody: common syllables 24 2.2.1. Plosives with liquids 26 2.2.2. S groups 29 2.2.3. Productio ob caesuram and consonantal h 34 2.2.4. Hiatus and correption 40 2.2.5. Hic and hoc 44 2.2.6. Summary 47 2.3. Other observations on prosody 49 2.4. The structure of the dactylic metres 58 2.4.1. The dactylic hexameter 58 2.4.2. The elegiac couplet 72 2.5. The aesthetics of verse 75 2.5.1.