Lecture 01 GENDER STUDIES: an INTRODUCTION Topic: 01-04

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shiism and Sectarian Conflict in Pakistan Identity Politics, Iranian Influence, and Tit-For-Tat Violence

Combating Terrorism Center at West Point Occasional Paper Series Shiism and Sectarian Conflict in Pakistan Identity Politics, Iranian Influence, and Tit-for-Tat Violence Hassan Abbas September 22, 2010 1 2 Preface As the first decade of the 21st century nears its end, issues surrounding militancy among the Shi‛a community in the Shi‛a heartland and beyond continue to occupy scholars and policymakers. During the past year, Iran has continued its efforts to extend its influence abroad by strengthening strategic ties with key players in international affairs, including Brazil and Turkey. Iran also continues to defy the international community through its tenacious pursuit of a nuclear program. The Lebanese Shi‛a militant group Hizballah, meanwhile, persists in its efforts to expand its regional role while stockpiling ever more advanced weapons. Sectarian violence between Sunnis and Shi‛a has escalated in places like Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Bahrain, and not least, Pakistan. As a hotbed of violent extremism, Pakistan, along with its Afghan neighbor, has lately received unprecedented amounts of attention among academics and policymakers alike. While the vast majority of contemporary analysis on Pakistan focuses on Sunni extremist groups such as the Pakistani Taliban or the Haqqani Network—arguably the main threat to domestic and regional security emanating from within Pakistan’s border—sectarian tensions in this country have attracted relatively little scholarship to date. Mindful that activities involving Shi‛i state and non-state actors have the potential to affect U.S. national security interests, the Combating Terrorism Center is therefore proud to release this latest installment of its Occasional Paper Series, Shiism and Sectarian Conflict in Pakistan: Identity Politics, Iranian Influence, and Tit-for-Tat Violence, by Dr. -

Pakistan Response Towards Terrorism: a Case Study of Musharraf Regime

PAKISTAN RESPONSE TOWARDS TERRORISM: A CASE STUDY OF MUSHARRAF REGIME By: SHABANA FAYYAZ A thesis Submitted to the University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Political Science and International Studies The University of Birmingham May 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The ranging course of terrorism banishing peace and security prospects of today’s Pakistan is seen as a domestic effluent of its own flawed policies, bad governance, and lack of social justice and rule of law in society and widening gulf of trust between the rulers and the ruled. The study focused on policies and performance of the Musharraf government since assuming the mantle of front ranking ally of the United States in its so called ‘war on terror’. The causes of reversal of pre nine-eleven position on Afghanistan and support of its Taliban’s rulers are examined in the light of the geo-strategic compulsions of that crucial time and the structural weakness of military rule that needed external props for legitimacy. The flaws of the response to the terrorist challenges are traced to its total dependence on the hard option to the total neglect of the human factor from which the thesis develops its argument for a holistic approach to security in which the people occupy a central position. -

Abbottabad Bahawalpur Faisalabad

Abbottabad 1 Muhammad Imran Afzal & Co. SBM-House No. 914, Behind Shalimar Motor, Near Sefhi Masjid, Mansehra Road, Abbottabad Email: [email protected] Bahawalpur 1 Usman Zafar & Co. 20-A, Cheema Town, Bahawalpur Faisalabad 1 A. Sattar & Co. Al Razzaq Center, P-119, 3rd Floor, Pak Gole Bazar, Amin Pur Bazar, Faisalabad Off. 2611812,0321-8838383 Fax. 2611812 Email: [email protected],[email protected] 2 Adnan Ali & Co. Office No. 501, 5th Floor, Galaxy Madina Center, Kohinoor City, Faisalabad Email: [email protected] 3 Agha Slam Tayyab Saad & Co. Sufi Tower, 17-Z,, Commercial Area, Opp. Mujahid Hospital, Madina Town, Faisalabad Off. 041-8401228,0345-7765288 4 Ahmad Jabbar & Co. Office # 1, 6th Floor, Legacy Tower, Kohinoor City Commercial Area, Faisalabad Off. 8502082-83,0301-8662019 Fax. 8502084 Email: [email protected] 5 Aisha Arshad & Co. 104 D/A, Sabri Chowk, Ghulam Muhammed Abad, Faisalabad Off. 041-2681635,0321-7600597 6 Akram & Co. Upper Storey HBL, West Canal Road, Near Toyota Motors, Faisalabad Off. 8724323,0300-9663451 Email: [email protected] 7 Akram Saleem & Co. Upper Storey HBL, West Canal Road, Near Toyota Motors, Faisalabad Off. 8724323,0300-9663451 Fax. 8724323 Email: [email protected] 8 Ali Akhtar Adnan Office # 1, 1st Floor, Noor Centre, Madina Town, Faisalabad Off. 8503441-3 9 Amin Mudassar & Co. 207-208, Hassan Shopping Mall, 20-A Peoples Colony, Faisalabad Off. 8718891-92 Fax. 8718893 Email: [email protected],[email protected] Faisalabad 10 Anas & Co. P-33, Satellite Town, Opp. Coca Cola Factory, Sumundri Road, Faisalabad Off. 2664541 11 Anas & Rehman P-17 A/B, Club Road, Civil Lines, Faisalabad Off. -

6455.Pdf, PDF, 1.27MB

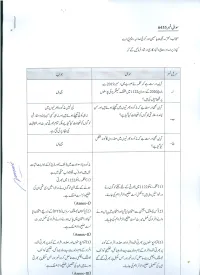

Overall List Along With Domicile and Post Name Father Name District Post Shahab Khan Siraj Khan PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Sana Ullah Muhammad Younas Lower Dir 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Mahboob Ali Fazal Rahim Swat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Tahir Saeed Saeed Ur Rehman Kohat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Owais Qarni Raham Dil Lakki Marwat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Ashfaq Ahmad Zarif Khan Charsadda 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Saud Khan Haji Minak Khan Khyber 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Qamar Jan Syed Marjan Kurram 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Kamil Khan Wakeel Khan PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Waheed Gul Muhammad Qasim Lakki Marwat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Tanveer Ahmad Mukhtiar Ahmad Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Muhammad Faheem Muhammad Aslam PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Muslima Bibi Jan Gul Dera Ismail Khan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Muhammad Zahid Muhammad Saraf Batagram 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Riaz Khan Muhammad Anwar Lower Dir 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Bakht Taj Abdul Khaliq Shangla 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Hidayat Ullah Fazal Ullah Swabi 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Wajid Ali Malang Jan Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Sahar Rashed Abdur Rasheed Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Afsar Khan Afridi Ghulam Nabi PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Adnan Khan Manazir Khan Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Liaqat Ali Malik Aman Charsadda 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Adnan Iqbal Parvaiz Khan Mardan 01. -

ETHNICITY, ISLAM and NATIONALISM Muslim Politics in the North-West Frontier Province (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 1937-1947

ETHNICITY, ISLAM AND NATIONALISM Muslim Politics in the North-West Frontier Province (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 1937-1947 Sayed Wiqar Ali Shah National Institute of Historical and Cultural Research Centre Of Excellence Quaid-I-Azam University (New Campus) Islamabad, Pakistan 2015 ETHNICITY, ISLAM AND NATIONALISM Muslim Politics in the North-West Frontier Province (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 1937-1947 NIHCR Publication No.171 Copyright 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing from the Director, National Institute of Historical and Cultural Research. Enquiries concerning reproduction should be sent to NIHCR at the address below. National Institute of Historical and Cultural Research, Centre of Excellence, Quaid-i-Azam University, (New Campus) P.O. Box No.1230, Islamabad - 44000, Pakistan. Email: [email protected] , [email protected] Website: www.nihcr.edu.pk Editing/Proofreading: Muhammad Saleem Title: Zahid Imran Published by Muhammad Munir Khawar, Publication Officer. Printed at M/s Roohani Art Press, Blue Area, Islamabad, Pakistan. Price Pak Rs.700.00 SAARC Countries Rs.900.00 ISBN: 978-969-415-113-7 US $.20.00 CONTENTS Map vi Acknowledgements vii Abbreviations x Introduction xii 1 NWFP and its Society 1 2 Government and Politics in the Province 15 3 The Frontier Congress in Office 1937-39 51 4 Revival of the Frontier Muslim League 91 5 Politics During the War Years 115 6 Moving Towards Communalization of Politics 153 7 Muslims of NWFP and Pakistan 183 Conclusion 233 Appendices I Statement of Khan Abdul Akbar Khan, President of the 241 Afghan Youth League and Mian Ahmad Shah, General Secretary of the Afghan Youth League, Charsadda II Speeches Delivered on the Occasion of the No-Confidence 249 Motion against Sir A. -

Femininity and Women Political Participation in Pakistan

73 The Pakistan Journal of Social Issues Volume VIII (2017) Femininity and Women Political Participation in Pakistan Akhlaq Ahmada and Haq Nawaz Anwarb Abstract Gender gaps in political participation are quite persistent and significant in both developed and under developing countries. However, femininity and political participation has very much less researched area. This study explains how are the dominant, hegemonic discourses of gender producing subordinate, submissive feminine identities that adhere to the masculine political connotations and result in the low political participation in Pakistan. Social constructionist understanding of gender is the underlying theoretical foundation of this article. This research engages qualitative research methodology and method includes in-depth interviews with 20 women selected purposefully, participant and non participant observation and various informal discussions with women informants. It can be concluded that domesticity ideology, gendered division of labor, traditional gender roles, strict division of private and public sphere, adherence to essentialist and biological determinism, hegemonic political structure and the emphasized femininity are characteristics of feminine identity in the Pakistan. This feminine identity is undermining women capabilities, creating social barrier and leaving meager spaces in the masculine political structure of Pakistan and hence, lowering the level of political participation. Introduction Gender gaps in political participation were found to be quite persistent and notable in the western, industrialized and democratic countries (e.g. Bennett & Bennett, 1992; Parry et al., 1992; Scholzman et al., 1995; Burns et al., 1997; Verba et al., 1997; Scholzman et al., 1999; Norris, 2002; Burns, 2007; Gallego, 2007; Paxton et al., 2007; Dalton, 2008) and a research area since 1950s. -

Unclaimed Deposit 2014

Details of the Branch DETAILS OF THE DEPOSITOR/BENEFICIARIYOF THE INSTRUMANT NAME AND ADDRESS OF DEPOSITORS DETAILS OF THE ACCOUNT DETAILS OF THE INSTRUMENT Transaction Federal/P rovincial Last date of Name of Province (FED/PR deposit or in which account Instrume O) Rate Account Type Currency Rate FCS Rate of withdrawal opened/instrume Name of the nt Type In case of applied Amount Eqv.PKR Nature of Deposit ( e.g Current, (USD,EUR,G Type Contract PKR (DD-MON- Code Name nt payable CNIC No/ Passport No Name Address Account Number applicant/ (DD,PO, Instrument NO Date of issue instrumen date Outstandi surrender (LCY,UFZ,FZ) Saving, Fixed BP,AED,JPY, (MTM,FC No (if conversio YYYY) Purchaser FDD,TDR t (DD-MON- ng ed or any other) CHF) SR) any) n , CO) favouring YYYY) the Governm ent 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 PRIX 1 Main Branch Lahore PB Dir.Livestock Quetta MULTAN ROAD, LAHORE. 54500 LCY 02011425198 CD-MISC PHARMACEUTICA TDR 0000000189 06-Jun-04 PKR 500 12-Dec-04 M/S 1 Main Branch Lahore PB MOHAMMAD YUSUF / 1057-01 LCY CD-MISC PKR 34000 22-Mar-04 1 Main Branch Lahore PB BHATTI EXPORT (PVT) LTD M/S BHATTI EXPORT (PVT) LTD M/SLAHORE LCY 2011423493 CURR PKR 1184.74 10-Apr-04 1 Main Branch Lahore PB ABDUL RAHMAN QURESHI MR ABDUL RAHMAN QURESHI MR LCY 2011426340 CURR PKR 156 04-Jan-04 1 Main Branch Lahore PB HAZARA MINERAL & CRUSHING IND HAZARA MINERAL & CRUSHING INDSTREET NO.3LAHORE LCY 2011431603 CURR PKR 2764.85 30-Dec-04 "WORLD TRADE MANAGEMENT M/SSUNSET LANE 1 Main Branch Lahore PB WORLD TRADE MANAGEMENT M/S LCY 2011455219 CURR PKR 75 19-Mar-04 NO.4,PHASE 11 EXTENTION D.H.A KARACHI " "BASFA INDUSTRIES (PVT) LTD.FEROZE PUR 1 Main Branch Lahore PB 0301754-7 BASFA INDUSTRIES (PVT) LTD. -

Pakistan, the Deoband ‘Ulama and the Biopolitics of Islam

THE METACOLONIAL STATE: PAKISTAN, THE DEOBAND ‘ULAMA AND THE BIOPOLITICS OF ISLAM by Najeeb A. Jan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Professor Juan R. Cole, Co-Chair Professor Nicholas B. Dirks, Co-Chair, Columbia University Professor Alexander D. Knysh Professor Barbara D. Metcalf HAUNTOLOGY © Najeeb A. Jan DEDICATION Dedicated to my beautiful mother Yasmin Jan and the beloved memory of my father Brian Habib Ahmed Jan ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people to whom I owe my deepest gratitude for bringing me to this stage and for shaping the world of possibilities. Ones access to a space of thought is possible only because of the examples and paths laid by the other. I must begin by thanking my dissertation committee: my co-chairs Juan Cole and Nicholas Dirks, for their intellectual leadership, scholarly example and incredible patience and faith. Nick’s seminar on South Asia and his formative role in Culture/History/Power (CSST) program at the University of Michigan were vital in setting the critical and interdisciplinary tone of this project. Juan’s masterful and prolific knowledge of West Asian histories, languages and cultures made him the perfect mentor. I deeply appreciate the intellectual freedom and encouragement they have consistently bestowed over the years. Alexander Knysh for his inspiring work on Ibn ‘Arabi, and for facilitating several early opportunity for teaching my own courses in Islamic Studies. And of course my deepest thanks to Barbara Metcalf for unknowingly inspiring this project, for her crucial and sympathetic work on the Deoband ‘Ulama and for her generous insights and critique. -

Conference Proceedings: Two-Day International Conference Held on Nov 15-16, 2017

CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS: TWO-DAY INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE HELD ON NOV 15-16, 2017 UNIVERSITY OF MALAKAND CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS PROBLEMS AND CHALLENGES TO ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING REFORMS IN RELIGIOUS MADRASSAS OF PAKISTAN TWO-DAY INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE NOVEMBER 15-16, 2017 ORGANIZED BY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF MALAKAND CHAKDARA DIR LOWER KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA IN COLLABORATION WITH HIGHER EDUCATION COMMISSION, PAKISTAN 1 PROBLEMS AND CHALLENGES TO ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING REFORMS IN RELIGIOUS MADRASSAS OF PAKISTAN PCELTRRMP CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS PROBLEMS AND CHALLENGES TO ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING REFORMS IN RELIGIOUS MADRASSAS OF PAKISTAN PCELTRRMP TWO-DAY INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE NOVEMBER 15-16, 2017 ORGANIZED BY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF MALAKAND CHAKDARA DIR LOWER KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA IN COLLABORATION WITH HIGHER EDUCATION COMMISSION, PAKISTAN 2 CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS: TWO-DAY INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE HELD ON NOV 15-16, 2017 Disclaimer With respect to the information / material contained herein, the publisher and reviewers hereby disclaim liability to any party for any loss, damage or disruption caused by an infringement of intellectual property rights, errors, omissions, misrepresentation, negligence or otherwise. The publisher and reviewers make no guarantee about the reliability, completeness and authenticity of the information / material contained herein. Copyright @ 2017 by Department of English, University of Malakand All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other non-commercial uses permitted by the copyright law. Printed in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan 3 PROBLEMS AND CHALLENGES TO ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING REFORMS IN RELIGIOUS MADRASSAS OF PAKISTAN PCELTRRMP TABLE OF CONTENTS S. -

The Pakistan Army Officer Corps, Islam and Strategic Culture 1947-2007

The Pakistan Army Officer Corps, Islam and Strategic Culture 1947-2007 Mark Fraser Briskey A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy UNSW School of Humanities and Social Sciences 04 July 2014 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT 'I hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or part in the University libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. I also authorise University Microfilms to use the 350 word abstract of my thesis in Dissertation Abstract International (this is applicable to doctoral theses only). I have either used no substantial portions of copyright material in my thesis or I have obtained permission to use copyright material; where permission has not been granted I have applied/ ·11 apply for a partial restriction of the digital copy of my thesis or dissertation.' Signed t... 11.1:/.1!??7 Date ...................... /-~ ....!VP.<(. ~~~-:V.: .. ......2 .'?. I L( AUTHENTICITY STATEMENT 'I certify that the Library deposit digital copy is a direct equivalent of the final officially approved version of my thesis. No emendation of content has occurred and if there are any minor Y, riations in formatting, they are the result of the conversion to digital format.' · . /11 ,/.tf~1fA; Signed ...................................................../ ............... Date . -

Masculine Politics and Women Political Participation in Punjab, Pakistan

MASCULINE POLITICS AND WOMEN POLITICAL PARTICIPATION IN PUNJAB, PAKISTAN By Akhlaq Ahmad 2015-GCUF-232270 Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of Requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In SOCIOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY GOVERNMENT COLLEGE UNIVERSITY, FAISALABAD August, 2017 1 DEDICATED TO MY LOVING FAMILY BUSHRA KHALID; MY WIFE & NOOR, MUHAMMAD AND MAFAZA; MY KIDS 2 DECLARATION The work reported in this thesis was carried out by me under the supervision of Professor Dr. Haq Nawaz Anwar Department of Sociology, Government College University, Faisalabad, Pakistan. I hereby declare that title of the thesis “Masculine politics and women political participation in Punjab, Pakistan” and the contents of the thesis are the product of my own research and no part of it has been copied from any published source (except the references, standard mathematical or genetic model/ equations/ formulas/protocols etc.). I further declare that this work has not been submitted for award of any other degree/diploma. The University may take action if the information provided is found inaccurate at any stage. Signature: ………………….. Akhlaq Ahmad 2015-GCUF-232270 3 CERTIFICATE BY SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE We certify that the contents and the form of the thesis submitted by Mr. Akhlaq Ahmad, registration No. 2015-GCUF-232270 has been found satisfactory and in accordance with the prescribed format. We recommend it to be processed for the evaluation by the External Examiners for the award of the degree. 1. Signature of Supervisor: …………………….. Name: Prof. Dr. Haq Nawaz Anwar Designation with Stamp: …………………….. 2. Signature of Member 1: …………………….. Name: Dr. Babak Mahmood Designation with Stamp: …………………….. 3. -

The Role of North West Frontier Province Women in the Freedom Struggle for Pakistan (1930-47)

The Role of North West Frontier Province Women in the Freedom Struggle for Pakistan (1930-47) Shabana Shamaas Gul Khattak & Akhtar Hussain National Institute of Historical and Cultural Research, Centre of Excellence, Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad 2018 The Role of North West Frontier Province Women in the Freedom Struggle for Pakistan (1930-47) NIHCR Publication No.204 Copyright 2018 All rights reserved. No part of this publication be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing from the Director, National Institute of Historical and Cultural Research, Centre of Excellence, New Campus, Quaid-i- Azam University, Islamabad. Enquiries concerning reproduction should be sent to NIHCR at the address below: National Institute of Historical and Cultural Research Centre of Excellence, Quaid-i-Azam University P.O. Box 1230, Islamabad-44000. Tel: +92-51-2896153-54; Fax: +92-51-2896152 Email: [email protected] or [email protected] Website: www.nihcr.edu.pk Published by Muhammad Munir Khawar, Publication Officer. Printed at I.F. Graphic, Fazlul Haq Road, Blue Area, Islamabad Price: Pakistan Rs. 500/- SAARC countries: Rs. 800/- ISBN: 978-969-415-130-4 Other countries: US$ 15/- We dedicated this book to our two eyes; our beloved parents Mammy aw Baba (Sonerin) Mr. & Mrs. Shamaas Gul Khattak And Mor aw Daji Mr. & Mrs. Rashid Ahmad Table of Contents Forewords viii Acknowledgements x List of Abbreviations xi Map of North West Frontier Province (NWFP) and xii