John Banville's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Et in Arcadia Ille – This One Is/Was Also in Arcadia"

99 BARBARA PUSCHMANN-NALENZ "Et in Arcadia ille – this one is/was also in Arcadia:" Human Life and Death as Comedy for the Immortals in John Banville's The Infinities Hermes the messenger of the gods quotes this slightly altered Latin motto (Banville 2009, 143). The original phrase, based on a quotation from Virgil, reads "et in Arcadia ego" and became known as the title of a painting by Nicolas Poussin (1637/38) entitled "The Arcadian Shepherds," in which the rustics mentioned in the title stumble across a tomb in a pastoral landscape. The iconography of a baroque memento mori had been followed even more graphically in an earlier picture by Giovanni Barbieri, which shows a skull discovered by two astonished shepherds. In its initial wording the quotation from Virgil also appears as a prefix in Goethe's autobiographical Italienische Reise (1813-17) as well as in Evelyn Waugh's country- house novel Brideshead Revisited (1945). The fictive first-person speaker of the Latin phrase is usually interpreted as Death himself ("even in Arcadia, there am I"), but the paintings' inscription may also refer to the man whose mortal remains in an idyllic countryside remind the spectator of his own inevitable fate ("I also was in Arcadia"). The intermediality and equivocacy of the motto are continued in The Infinities.1 The reviewer in The Guardian ignores the unique characteristics of this book, Banville's first literary novel after his prize-winning The Sea, when he maintains that "it serves as a kind of catalogue of his favourite themes and props" (Tayler 2009). -

Poetry, Place, and Spiritual Practices by Katharine Bubel BA, Trinity

Edge Effects: Poetry, Place, and Spiritual Practices by Katharine Bubel B.A., Trinity Western University, 2004 M.A., Trinity Western University, 2009 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English Katharine Bubel, 2018 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Edge Effects: Poetry, Place, and Spiritual Practices by Katharine Bubel B.A., Trinity Western University, 2004 M.A., Trinity Western University, 2009 Supervisory Committee Dr. Nicholas Bradley, Department of English Supervisor Dr. Magdalena Kay, Department of English Departmental Member Dr. Iain Higgins, Department of English Departmental Member Dr. Tim Lilburn, Department of Writing Outside Member iii Abstract "Edge Effects: Poetry, Place, and Spiritual Practices” focusses on the intersection of the environmental and religious imaginations in the work of five West Coast poets: Robinson Jeffers, Theodore Roethke, Robert Hass, Denise Levertov, and Jan Zwicky. My research examines the selected poems for their reimagination of the sacred perceived through attachments to particular places. For these writers, poetry is a constitutive practice, part of a way of life that includes desire for wise participation in the more-than-human community. Taking into account the poets’ critical reflections and historical-cultural contexts, along with a range of critical and philosophical sources, the poetry is examined as a discursive spiritual exercise. It is seen as conjoined with other focal practices of place, notably meditative walking and attentive looking and listening under the influence of ecospiritual eros. -

The ESSE Messenger

The ESSE Messenger A Publication of ESSE (The European Society for the Study of English Vol. 26-2 Winter 2017 ISSN 2518-3567 All material published in the ESSE Messenger is © Copyright of ESSE and of individual contributors, unless otherwise stated. Requests for permissions to reproduce such material should be addressed to the Editor. Editor: Dr. Adrian Radu Babes-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca, Romania Faculty of Letters Department of English Str. Horea nr. 31 400202 Cluj-Napoca Romania Email address: [email protected] Cover illustration: Jane Austen’s Reading Nook at Chawton House Picture credit: Alexandru Paul Margau Contents Jane Austen Ours 5 Bringing the Young Ladies Out Carmen María Fernández Rodríguez 5 Understanding Jane Austen Miguel Ángel Jordán Enamorado 18 A Historical Reflection on Jane Austen’s Popularity in Spain Isis Herrero López 27 Authorial Realism or how I Learned that Jane Was a Person Alexandru Paul Mărgău 40 Adaptations, Sequels and Success Anette Svensson 46 Reviews 59 Herrero, Dolores and Sonia Baelo-Allue (eds.), The Splintered Glass: Facets of Trauma in the Post-Colony and Beyond. Cross Cultures 136. (Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2011). Irene Visser 59 Nancy Ellen Batty, The Ring of Recollection: Transgenerational Haunting in the Novels of Shashi Deshpande (New York: Amsterdam, 2010). Rabindra Kumar Verma 63 Konstantina Georganta, Conversing Identities: Encounters between British, Irish and Greek Poetry, 1922-1952 (Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2012). Aidan O’Malley 64 George Z. Gasyna, Polish, Hybrid, and Otherwise: Exilic Discourse in Joseph Conrad and Witold Gombrowicz (London: Continuum, 2011). Noelia Malla García 66 David Tucker, Samuel Beckett and Arnold Geulincx: Tracing a literary fantasia. -

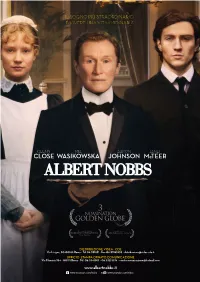

Albert Nobbs Notes FINAL 10.8.11 ITA

3 NOMINATION GOLDEN GLOBE ® DISTRIBUZIONE VIDEA 5 CDE Via Livigno, 50-00188 Roma - Tel 06.331851 - Fax 06.33185255 - [email protected] UFFICIO STAMPA ORNATO COMUNICAZIONE Via Flaminia 954 - 00191 Roma - Tel. 06.3341017 - 06.33213374 - [email protected] www.albertnobbs.it www.facebook.com/videa www.youtube.com/videa Sinossi La pluripremiata attrice Glenn Close (Albert Nobbs) indossa i panni di una donna coinvolta in un insolito triangolo amoroso. Travestita da uomo per poter lavorare e sopravvivere nell’Irlanda del XIX secolo, più di trent’anni dopo si ritrova prigioniera della sua stessa finzione. Nel prestigioso cast internazionale, Mia Wasikowska (Helen), Aaron Johnson (Joe) e Brendan Gleeson (Dr. Holloran), oltre a Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Janet McTeer, Brenda Fricker e Pauline Collins. Rodrigo Garcia dirige il film basato su un racconto dell’autore irlandese George Moore, adattato da Glenn Close insieme a John Banville, vincitore del premio Man Booker, e a Gabriella Prekop. NOTE DI PRODUZIONE IL LEGAME DI GLENN CLOSE con il personaggio di Albert Nobbs risale a Quasi 30 anni fa, ai tempi in cui recitò – nel 1982 – nella rappresentazione teatrale di Simone Benmussa, ispirata al racconto breve Albert Nobbs, scritto dall’autore irlandese del XIX secolo, George Moore. “Credo che Albert sia un grande personaggio e la storia, in tutta la sua disarmante semplicità, è molto potente dal punto di vista emotivo”, dichiara Close, la cui apparizione in Quella produzione Off-Broadway le valse critiche eccellenti e un Obie Award. Nonostante i grandi successi che Close ha collezionato nel corso della sua brillante carriera, quel personaggio le è rimasto dentro. -

Albert Nobbs

Albert Nobbs Albert Nobbs, ALBERT NOBBS, RODRIGO GARCIA, Golden Globe Award, role, characters, film credits, John Banville, John Boorman, Julie Lynn, starring role, television, Simone Benmussa, Brendan Gleeson, Radha Mitchell, Harry Potter, Aaron Johnson, Los Angeles Film Critics Association, Los Angeles Drama Critics Circle Award, George Roy Hill, Kerry Washington, Margarethe Cammermeyer, Mia Wasikowska, Joe Layton, Directors' Fortnight, Neil Jordan, BBC comedy series, Florida Film Festival, European Film Academy, award nomination, Arlene Kelly, Sweet Emma Dear Bobe, Dublin Theatre Festival, television drama, Michael Cristofer, Franco Zeffirelli, Harvey Goldsmith, Winner Locarno Film Festival, Harold Prince, Irish actor, Fountain House, Andrew Lloyd Webber, Richard Pearce, Norma Desmond, Merchant Ivory, Stephen Frears, Jack Hofsiss, Stephen Herek, Royal National Theatre, Tony Awards, Richard Marquand, Fatal Attraction, Feature Film Commission, Christopher Walken, Barbet Schroeder, Joe, MAIN characters, National Association of Theatre Owners, Andrei Konchalovsky, International Mental Health Research Organization, Monica Rawling, Glenn Jordan, Rose Troche, Panthera Conservation Advisory Committee, Julian Morris, Danny Boyle, JOE Aaron Johnson, British independent film, Kristen Scott Thomas, Golden Globe nomination, Simon Wincer, Colin Farrell, RODRIGO GARCIA GABRIELLA PREKOP JOHN BANVILLE GLENN CLOSE, GLENN CLOSE, Bonnie Curtis, John Travolta, Golden Globe, Michael Vartan, John Lennon, Rhys Meyers, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, London Film Critics, -

Banville and Lacan: the Matter of Emotions in the Infinities Banville E Lacan: a Questão Das Emoções Em the Infinities

ABEI Journal — The Brazilian Journal of Irish Studies, v.22, n.1, 2020, p. 147-158 Banville and Lacan: The Matter of Emotions in The Infinities Banville e Lacan: A Questão das Emoções em The Infinities Hedwig Schwall Abstract: Both Banville and Lacan are Freudian interpreters of the postmodern world. Both replace the classic physical-metaphysical dichotomy with a focus on the materiality of communication in an emophysical world. Both chart the ways in which libidinal streams combine parts of the self and link the self with other people and objects. These interactions take place in three bandwidths of perception, which are re-arranged by the uncanny object a. This ‘object’ reawakens the affects of the unconscious which infuse the identity formations with new energy. In this article we look briefly at how the object a is realised in The Book of Evidence, Ghosts and Eclipse to focus on how it works in The Infinities, especially in the relations between Adam Godley junior and senior, Helen and Hermes. Keywords: Banville and Lacan; emotions; The Infinities; Object a; Scopic drive; the libidinal Real Resumo: Banville e Lacan são intérpretes freudianos do mundo pós-moderno. Ambos substituem a dicotomia físico-metafísica clássica pelo foco na materialidade da comunicação em um mundo emofísico. Ambos traçam a diferentes maneiras pelas quais os fluxos libidinais combinam partes do eu e vinculam o eu a outras pessoas e objetos. Essas interações ocorrem em três larguras de banda da percepção, que são reorganizadas pelo objeto misterioso a. Esse “objeto” desperta os afetos do inconsciente que infundem as formações identitárias com nova energia. -

The Sea. John Banville. Knopf: New York, 2005. Paperback, 195 Pages

e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies Volume 9 Book Reviews Article 4 8-18-2006 The eS a. John Banville. Knopf: New York, 2005. Paperback, 195 pages. ISBN 0-30726- 311-8. Matthew rB own University of Massachusetts – Boston Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi Recommended Citation Brown, Matthew (2006) "The eS a. John Banville. Knopf: New York, 2005. Paperback, 195 pages. ISBN 0-30726- 311-8.," e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies: Vol. 9 , Article 4. Available at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi/vol9/iss1/4 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact open- [email protected]. The Sea. John Banville. Knopf: New York, 2005. Paperback, 195 pages. ISBN 0-30726- 311-8. $23.00. Matthew Brown, University of Massachusetts-Boston To the surprise of many, John Banville's The Sea won the 2005 Booker prize for fiction, surprising because of all of Banville's dazzlingly sophisticated novels, The Sea seems something of an afterthought, a remainder of other and better books. Everything about The Sea rings familiar to readers of Banville's oeuvre, especially its narrator, who is enthusiastically learned and sardonic and who casts weighty meditations on knowledge, identity, and art through the murk of personal tragedy. This is Max Morden, who sounds very much like Alexander Cleave from Eclipse (2000), or Victor Maskell from The Untouchable (1997). -

The Quest for God in the Novels of John Banville 1973-2005: a Postmodern Spiritualily

THE QUEST FOR GOD IN THE NOVELS OF JOHN BANVILLE 1973-2005: A POSTMODERN SPIRITUALITY Brendan McNamee Lewiston, Queenson, Lampeter: The Edwin Mellen Press. 2006 (by Violeta Delgado Crespo. Universidad de Zaragoza) [email protected] 121 As McNamee puts it in his study, it seems that “the ultimate aim of Banville’s fiction is to elude interpretation” (6). It is perhaps this elusiveness that ensures a growing number of critical contributions on the work of a writer who has explicated his aesthetic, his view of art in general, and literature in particular, in talks, interviews and varied writings. McNamee’s is the seventh monographic study of John Banville’s work published to date, and claims to differ from the previous six by widening the cultural context in which the work of the Irish writer has been read. Although, to my knowledge, John Banville has never defined himself in these terms, McNamee portrays him as an essentially religious writer (13) when he foregrounds the deep spiritual yearning that Banville’s fiction exhibits in combination with the many postmodern elements (paradox and parody, self- reflexivity, intertextuality) that are familiar in his novels. To McNamee, Banville’s enigmatic fictions allow for a link between the disparate phenomena of pre-modern mysticism and postmodernism, suggesting that many aspects of the postmodern sensibility veer toward the spiritual. He considers the language of Banville’s fiction intrinsically mystical, an artistic form of what is known as apophatic language, which he defines as “the mode of writing with which mystics attempt to say the unsayable” (170). In terms of style, Banville’s writing approaches the ineffable: that which cannot be paraphrased or described. -

“The Ghost of That Ineluctable Past”: Trauma and Memory in John Banville’S Frames Trilogy GPA: 3.9

“THE GHOST OF THAT INELUCTABLE PAST”: TRAUMA AND MEMORY IN JOHN BANVILLE’S FRAMES TRILOGY BY SCOTT JOSEPH BERRY A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS English December, 2016 Winston-Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Jefferson Holdridge, PhD, Advisor Barry Maine, PhD, Chair Philip Kuberski, PhD ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To paraphrase John Banville, this finished thesis is the record of its own gestation and birth. As such, what follows represents an intensely personal, creative journey for me, one that would not have been possible without the love and support of some very important people in my life. First and foremost, I would like to thank my wonderful wife, Kelly, for all of her love, patience, and unflinching confidence in me throughout this entire process. It brings me such pride—not to mention great relief—to be able to show her this work in its completion. I would also like to thank my parents, Stephen and Cathyann Berry, for their wisdom, generosity, and support of my every endeavor. I am very grateful to Jefferson Holdridge, Omaar Hena, Mary Burgess-Smyth, and Kevin Whelan for their encouragement, mentorship, and friendship across many years of study. And to all of my Wake Forest friends and colleagues—you know who you are—thank you for your companionship on this journey. Finally, to Maeve, Nora, and Sheilagh: Daddy finally finished his book. Let’s go play. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………...iv -

The Archaic Shudder? Toward a Poetics of the Sublime (In Two Sections: Creative and Critical)

Title The Archaic Shudder? Toward a poetics of the sublime (in two sections: creative and critical) Student Name Dan Disney Diploma of Arts (Editing), RMIT Bachelor of Arts, Monash University Master of Creative Arts (Research), University of Melbourne This thesis is submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by creative work (50%) and dissertation (50%), School of Culture and Communication, University of Melbourne. Submitted 15th September, 2009. 1 2 Abstract This cross-disciplinary investigation moves toward that sub-genre in aesthetics, the theory of creativity. After introducing my study with a re-reading of Heidegger’s essay, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, I appropriate into a collection of poems ideas from Plato, Kant, Heidegger, Wittgenstein, and a range of post-philosophical theorists. Next, after Murmur and Afterclap, in the critical section of my investigation I formulate a poetics of the sublime, and move closer to my own specialist term, poeticognosis. With this term, I set out to designate a particular style of apprehending-into-language, after wonder, as it pertains (I argue) to creative producers. Section One Murmur and Afterclap The poetry submitted here does not arise simply out of a theoretical position or theoretical concerns, and it is not in any sense exemplary or programmatic. It is, however, related in complex ways to the issues raised later in the critical section of my investigation, and indeed has provoked − necessitated − my theoretical discussion (rather than the other way around). The poems contained in this section of my investigation draw from the many documents I have encountered in my attempt to shape a discourse with philosophy. -

John Banville's

Études irlandaises 43-2 | 2018 Varia John Banville’s “Overman”: Intertextual dialogues with Friedrich Nietzsche in Shroud Mehdi Ghassemi Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/etudesirlandaises/5826 DOI: 10.4000/etudesirlandaises.5826 ISSN: 2259-8863 Publisher Presses universitaires de Caen Printed version Date of publication: 18 December 2018 Number of pages: 159-181 ISBN: 978-2-7535-7693-3 ISSN: 0183-973X Electronic reference Mehdi Ghassemi, « John Banville’s “Overman”: Intertextual dialogues with Friedrich Nietzsche in Shroud », Études irlandaises [Online], 43-2 | 2018, Online since 01 November 2018, connection on 22 September 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/etudesirlandaises/5826 ; DOI : 10.4000/ etudesirlandaises.5826 © Presses universitaires de Rennes John Banville’s “Overman”: Intertextual dialogues with Friedrich Nietzsche in Shroud Mehdi Ghassemi Université de Lille Résumé Cet article propose de lire Shroud (2003) de John Banville comme exemple qui illustre le mieux le dialogue de l’écrivain avec la philosophie de Friedrich Nietzsche. Cette étude tente de retracer les manières dont le narrateur incorpore et ensuite réinvente la notion Nietzschéenne de l’homme (Übermensch) à travers de ses métaphores élaborées. Ce projet soutient également que c’est bien Nietzsche qui fournit finalement au narrateur banvillean l’outil nécessaire pour encadrer une conception du “moi” qui serait immune à la crise linguistique proposée par la déconstruction. Mots clés: Banville, Shroud, Nietzsche, authenticité, déconstruction Abstract This paper proposes to read John Banville’s Shroud (2003) as an example that most aptly illus- trates the writer’s dialogue with the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche. It traces the ways in which Banville’s narrator incorporates Nietzsche’s conception of self and demonstrates how Banville rein- vents Nietzsche’s idea of the Overman through elaborate metaphors. -

May, Talitha 01-27-18

Writing the Apocalypse: Pedagogy at the End of the World A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Talitha May May 2018 © 2018 Talitha May. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Writing the Apocalypse: Pedagogy at the End of the World by TALITHA MAY has been approved for the Department of English and the College of Arts and Sciences by Sherrie L. Gradin Professor of English Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT MAY, TALITHA, Ph.D., May 2018, English Writing the Apocalypse: Pedagogy at the End of the World Director of Dissertation: Sherrie L. Gradin Beset with political, social, economic, cultural, and environmental degradation, along with the imminent threat of nuclear war, the world might be at its end. Building upon Richard Miller’s inquiry from Writing at the End of the World, this dissertation investigates if it is “possible to produce [and teach] writing that generates a greater connection to the world and its inhabitants.” I take up Paul Lynch’s notion of the apocalyptic turn and suggest that when writers Kurt Spellmeyer, Richard Miller, Derek Owens, Robert Yagelski, Lynn Worsham, and Ann Cvetkovich confront disaster, they reach an impasse whereby they begin to question disciplinary assumptions such as critique and pose inventive ways to think about writing and writing pedagogy that emphasize the notion and practice of connecting to the everyday. Questioning the familiar and cultivating what Jane Bennett terms “sensuous enchantment with everyday” are ethical responses to the apocalypse; nonetheless, I argue that disasters and death master narratives will continually resurface if we think that an apocalyptic mindset can fully account for the complexity and irreducibility of lived experience.