The Archaic Shudder? Toward a Poetics of the Sublime (In Two Sections: Creative and Critical)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond Good and Evil

Beyond Good and Evil Friedrich Nietzsche Helen Zimmern translation PREFACE SUPPOSING that Truth is a woman—what then? Is there not ground for suspecting that all philosophers, in so far as they have been dogmatists, have failed to understand women—that the terrible seriousness and clumsy importunity with which they have usually paid their addresses to Truth, have been unskilled and unseemly methods for winning a woman? Certainly she has never allowed herself to be won; and at present every kind of dogma stands with sad and discouraged mien—IF, indeed, it stands at all! For there are scoffers who maintain that it has fallen, that all dogma lies on the ground— nay more, that it is at its last gasp. But to speak seriously, there are good grounds for hoping that all dogmatizing in philosophy, whatever solemn, whatever conclusive and decided airs it has assumed, may have been only a noble puerilism and tyronism; and probably the time is at hand when it will be once and again understood WHAT has actually sufficed for the basis of such imposing and absolute philosophical edifices as the dogmatists have hitherto reared: perhaps some popular superstition of immemorial time (such as the soul-superstition, which, in the form of subject- and ego-superstition, has not yet ceased doing mischief): perhaps some play upon words, a deception on the part of grammar, or an audacious generalization of very restricted, very personal, very human— all-too-human facts. The philosophy of the dogmatists, it is to be hoped, was only a promise for thousands of years afterwards, as was astrology in still earlier times, in the service of which probably more labour, gold, acuteness, and patience have been spent than on any actual science hitherto: we owe to it, and to its "super- terrestrial" pretensions in Asia and Egypt, the grand style of architecture. -

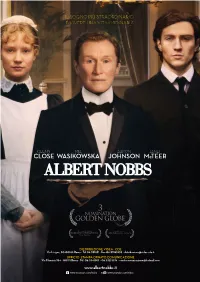

Albert Nobbs Notes FINAL 10.8.11 ITA

3 NOMINATION GOLDEN GLOBE ® DISTRIBUZIONE VIDEA 5 CDE Via Livigno, 50-00188 Roma - Tel 06.331851 - Fax 06.33185255 - [email protected] UFFICIO STAMPA ORNATO COMUNICAZIONE Via Flaminia 954 - 00191 Roma - Tel. 06.3341017 - 06.33213374 - [email protected] www.albertnobbs.it www.facebook.com/videa www.youtube.com/videa Sinossi La pluripremiata attrice Glenn Close (Albert Nobbs) indossa i panni di una donna coinvolta in un insolito triangolo amoroso. Travestita da uomo per poter lavorare e sopravvivere nell’Irlanda del XIX secolo, più di trent’anni dopo si ritrova prigioniera della sua stessa finzione. Nel prestigioso cast internazionale, Mia Wasikowska (Helen), Aaron Johnson (Joe) e Brendan Gleeson (Dr. Holloran), oltre a Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Janet McTeer, Brenda Fricker e Pauline Collins. Rodrigo Garcia dirige il film basato su un racconto dell’autore irlandese George Moore, adattato da Glenn Close insieme a John Banville, vincitore del premio Man Booker, e a Gabriella Prekop. NOTE DI PRODUZIONE IL LEGAME DI GLENN CLOSE con il personaggio di Albert Nobbs risale a Quasi 30 anni fa, ai tempi in cui recitò – nel 1982 – nella rappresentazione teatrale di Simone Benmussa, ispirata al racconto breve Albert Nobbs, scritto dall’autore irlandese del XIX secolo, George Moore. “Credo che Albert sia un grande personaggio e la storia, in tutta la sua disarmante semplicità, è molto potente dal punto di vista emotivo”, dichiara Close, la cui apparizione in Quella produzione Off-Broadway le valse critiche eccellenti e un Obie Award. Nonostante i grandi successi che Close ha collezionato nel corso della sua brillante carriera, quel personaggio le è rimasto dentro. -

Albert Nobbs

Albert Nobbs Albert Nobbs, ALBERT NOBBS, RODRIGO GARCIA, Golden Globe Award, role, characters, film credits, John Banville, John Boorman, Julie Lynn, starring role, television, Simone Benmussa, Brendan Gleeson, Radha Mitchell, Harry Potter, Aaron Johnson, Los Angeles Film Critics Association, Los Angeles Drama Critics Circle Award, George Roy Hill, Kerry Washington, Margarethe Cammermeyer, Mia Wasikowska, Joe Layton, Directors' Fortnight, Neil Jordan, BBC comedy series, Florida Film Festival, European Film Academy, award nomination, Arlene Kelly, Sweet Emma Dear Bobe, Dublin Theatre Festival, television drama, Michael Cristofer, Franco Zeffirelli, Harvey Goldsmith, Winner Locarno Film Festival, Harold Prince, Irish actor, Fountain House, Andrew Lloyd Webber, Richard Pearce, Norma Desmond, Merchant Ivory, Stephen Frears, Jack Hofsiss, Stephen Herek, Royal National Theatre, Tony Awards, Richard Marquand, Fatal Attraction, Feature Film Commission, Christopher Walken, Barbet Schroeder, Joe, MAIN characters, National Association of Theatre Owners, Andrei Konchalovsky, International Mental Health Research Organization, Monica Rawling, Glenn Jordan, Rose Troche, Panthera Conservation Advisory Committee, Julian Morris, Danny Boyle, JOE Aaron Johnson, British independent film, Kristen Scott Thomas, Golden Globe nomination, Simon Wincer, Colin Farrell, RODRIGO GARCIA GABRIELLA PREKOP JOHN BANVILLE GLENN CLOSE, GLENN CLOSE, Bonnie Curtis, John Travolta, Golden Globe, Michael Vartan, John Lennon, Rhys Meyers, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, London Film Critics, -

Talking Leaves 2009-2010

TALKING LEAVES COPYRIGHT 2009-2010 II Talking Leaves Staff Production Editors Oshu Huddleston, Senior Editor Cole Billman, Assistant Editor Production Assistant Joe Land Faculty Sponsor Lisa Siefker Bailey, Ph.D. Advisory Editor Katherine V. Wills, Ph.D. Copy Editors Jerry Baker Cole Billman Lindsey Daugherty Oshu Huddleston Abby Jones Joe Land Copyright 2009-2010 by the Trustees of Indiana University. Upon publication, copyright reverts to the author/artist. We retain the right to electronically archive and publish all issues for posterity and the general public. Talking Leaves is published annually by the Talking Leaves IUPUC Division of Liberal Arts Editorial Board. Statement of Policy and Purpose Talking Leaves accepts original works of fiction, poetry, photography, and line drawings from students at Indiana University- Purdue University Columbus. Each anonymous submission is reviewed by a Selection Roundtable and is judged solely on artistic merit. III IV TABLE OF CONTENTS VII – A WORD FROM THE FACULTY SPONSOR 1 - Beachcomber - poem by Beth McQueen 1 - The Flight - poem by Cole Billman 2 - Drifting - poem by Sarah Akemon 3 - Water PROOF - poem by Joe Land 4 - Noir Goode - short fiction by Oshu Huddleston 7 - Untitled (Short heaves) - poem by Joe Land 8 - National Treasure - poem by Sarah Akemon 8 - Untitled (1) - poem by Beth McQueen 8 - Untitled (2) - poem by Beth McQueen 9 - what is this sedentary thing - poem by Joe Land 9 - In the Hour of Our Death - poem by Sarah Akemon 10 - Write Shitty - poem by Sherry Traylor 10 - Blah. Eck! -

John Banville's

Études irlandaises 43-2 | 2018 Varia John Banville’s “Overman”: Intertextual dialogues with Friedrich Nietzsche in Shroud Mehdi Ghassemi Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/etudesirlandaises/5826 DOI: 10.4000/etudesirlandaises.5826 ISSN: 2259-8863 Publisher Presses universitaires de Caen Printed version Date of publication: 18 December 2018 Number of pages: 159-181 ISBN: 978-2-7535-7693-3 ISSN: 0183-973X Electronic reference Mehdi Ghassemi, « John Banville’s “Overman”: Intertextual dialogues with Friedrich Nietzsche in Shroud », Études irlandaises [Online], 43-2 | 2018, Online since 01 November 2018, connection on 22 September 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/etudesirlandaises/5826 ; DOI : 10.4000/ etudesirlandaises.5826 © Presses universitaires de Rennes John Banville’s “Overman”: Intertextual dialogues with Friedrich Nietzsche in Shroud Mehdi Ghassemi Université de Lille Résumé Cet article propose de lire Shroud (2003) de John Banville comme exemple qui illustre le mieux le dialogue de l’écrivain avec la philosophie de Friedrich Nietzsche. Cette étude tente de retracer les manières dont le narrateur incorpore et ensuite réinvente la notion Nietzschéenne de l’homme (Übermensch) à travers de ses métaphores élaborées. Ce projet soutient également que c’est bien Nietzsche qui fournit finalement au narrateur banvillean l’outil nécessaire pour encadrer une conception du “moi” qui serait immune à la crise linguistique proposée par la déconstruction. Mots clés: Banville, Shroud, Nietzsche, authenticité, déconstruction Abstract This paper proposes to read John Banville’s Shroud (2003) as an example that most aptly illus- trates the writer’s dialogue with the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche. It traces the ways in which Banville’s narrator incorporates Nietzsche’s conception of self and demonstrates how Banville rein- vents Nietzsche’s idea of the Overman through elaborate metaphors. -

Memories, Expressions, Reflections

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Honors Program Senior Projects WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Winter 2021 The Mountain and Me: Memories, Expressions, Reflections Corey Griffis Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors Part of the Creative Writing Commons Recommended Citation Griffis, Corey, "The Mountain and Me: Memories, Expressions, Reflections" (2021). WWU Honors Program Senior Projects. 431. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors/431 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Honors Program Senior Projects by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Note: the following is an adapted excerpt from a much larger, as-yet-unfinished book/memoir project. I began this book project as a Senior Capstone, and it ultimately extended beyond what I could complete before I graduated. I continue to work on this larger memoir; until that time, I have selected the following adapted excerpt for formal submission and archival. This adapted excerpt consists of chronologically separated chapters that are linked by place: together, they describe the important role that my experiences on Mount St. Helens have played in shaping my sense of self and perspective on life and living. The excerpts have been edited and extended in order to function more cohesively as a standalone piece, but they are still, at heart, part of a larger picture that has yet to fully take shape. It is my goal and hope that, sooner rather than later, I will be able to complete that picture and place it here as a more fully-realized creative product. -

Thorn's Chronicle

Thorn’s Chronicle Wake of ! White Witch’s Wra" Waning quarter moon of the Deep Snows (on or about Kaldmont 21, 997AC)! 2 Eve of the Chimerids (on or about Kaldmont 23, 997AC)! 16 First night of the Chimerids (on or about Kaldmont 24, 997AC)! 44 Second night of the Chimerids (on or about Kaldmont 25, 997AC)! 137 Last of the Longwinter"s Year (on or about Kaldmont 28, 997AC)! 169 Waning quarter moon of the Deep Snows (on or about Kaldmont 21, 997AC) The trip must have taken a mere step, the time it takes to draw a breath and let it go, and yet it seemed to stretch for much longer than that, as if I were dreaming it. There was no sound, nothing to see save the blinding blue-white light and the gut-twisting sensation of falling headlong off a cliff. And then everything came back all at once: A roaring of thunder (thankfully with no demonic echo); the sound of water slapping at the sides of a boat; shouts muffled by the surge of water. I flailed my arms and legs, found the movements heavy, sluggish. I tried to draw breath and instead got a mouthful of cold water. Fresh water, not salt. There was no sensation of anything below me but more water. I struggled as my head went under again, flailing back to the surface. Water still stung my eyes, sheeted down my brow. Rain. Cold rain. Not cold enough for snow, or even sleet. Cold enough, though, that I dared not wipe my eyes clear, or risk another dip into the near- freezing water. -

GENRE and CODE in the WORK of JOHN BANVILLE Kevin Boyle

GENRE AND CODE IN THE WORK OF JOHN BANVILLE Kevin Boyle St. Patrick’s College, Drumcondra Dublin City University School of Humanities Department of English Supervisor: Dr Derek Hand A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD April 2016 I hereby certify that this material, which T now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of PhD is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed:_____________________________ ID No.: 59267054_______ Date: Table of contents Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 4 Introduction: Genre and the Intertcxlual aspects of Banville's writing 5 The Problem of Genre 7 Genre Theory 12 Transgenerie Approach 15 Genre and Post-modernity' 17 Chapter One: The Benjamin Black Project: Writing a Writer 25 Embracing Genre Fiction 26 Deflecting Criticism from Oneself to One Self 29 Banville on Black 35 The Crossover Between Pseudonymous Authorial Sell'and Characters 38 The Opposition of Art and Craft 43 Change of Direction 45 Corpus and Continuity 47 Personae Therapy 51 Screen and Page 59 Benjamin Black and Ireland 62 Guilt and Satisfaction 71 Real Individuals in the Black Novels 75 Allusions and Genre Awareness 78 Knowledge and Detecting 82 Chapter Two: Doctor Copernicus, Historical Fiction and Post-modernity: -

Rova Saxophone Quartet & Nels Cline Singers: the Celestial Septet

Rova Saxophone Quartet & Nels Cline Singers: The Celestial Septet Actualizado: 20/3/2010 - 18:09 By Sergio Piccirilli César Chávez, Trouble Ticket, Whose to Know (for Albert Ayler), Head Count, The Buried Quilt Músicos: Bruce Ackley: saxo soprano, saxo tenor Steve Adams: saxo alto, saxo sopranino Scott Amendola: batería Nels Cline: guitarra Devin Hoff: bajo Larry Ochs: saxo tenor, saxo sopranino Jon Raskin: saxo barítono, saxo sopranino, saxo alto New World Records, 2010 Calificación: A la marosca No preguntemos si estamos plenamente de acuerdo, sino tan solo si marchamos por el mismo camino (Johann Wolfgang Goethe) Los estudios más minuciosos sobre el comportamiento en la gente creativa han demostrado de forma incontrastable que la creatividad está asociada a la capacidad para la ruptura de límites, la asunción de riesgos en búsqueda de nuevas ideas y la generación de alternativas a las prácticas convencionales. La creatividad, como decía el psicólogo gestáltico Joseph Zinker, “es la celebración de nuestra propia grandeza, el sentimiento de que podemos hacer que cualquier cosa se vuelva posible… es un acto de valentía, es la justificación de nuestro propósito de vivir”. La creatividad suele manifestarse como un acto individual e indelegable a través del cual exteriorizamos nuestro mundo interior. Sin embargo, la creatividad también puede revelarse de manera colectiva mediante la noción de un grupo de personas unidas en la creación de un único objeto. Apostar a la creación colectiva no implica uniformidad pero exige unanimidad; y esa concepción de lo unánime implica la suficiente amplitud de criterio para aceptar la existencia del otro sin poner en tela de juicio sus características y aceptando tácitamente la acción de ceder como dispositivo generador de acuerdos. -

Liner Notes, Visit Our Web Site

“When we escape from the place we spend most of our time . we start thinking about obscure possibilities . that never would have occurred to us if we’d stayed back on the farm.” —Jonah Lerner 1 In his 2009 essay about the transformative power of travel, science writer Jonah Lerner concludes, “When we get home, home is still the same. But something in our mind has been changed, and that changes everything.” The same thing can be said about listening to music, especially music that causes you to lose your bearings in a territory that cannot be fenced into any familiar category. The Celestial Septet, comprising the Nels Cline Singers and Rova Saxophone Quartet, is a vehicle for time and space travel through dense, narrow thickets and airy, wide expanses of boundary-blurred extrapolations of jazz, rock, late-20th-century European modernism and American minimalism, and 21st-century postmodern fusions. The trip is challenging, but the open-minded listener/traveler cannot help but come through the experience with new perspectives on sound and music. As individual entities, the Singers and Rova ramble in musical regions that have been variously and inadequately called “avant-garde,” “creative,” “improvised,” “new,” “noise,” and “free.” Such labels are more convenient than instructive. Similarly, the groups’ respective names are somewhat deceptive and limited when it comes to describing the configurations of personnel and instrumentation. The singer-less Singers—Nels Cline, Devin Hoff, and Scott Amendola—are ostensibly a guitar-bass-drums trio. But the approaches taken by Cline on acoustic and electric guitars and various effects, Hoff on acoustic contrabass, and Amendola on drum kit, percussion, live electronics, and effects expand the threesome’s musical possibilities exponentially. -

Ttu Mac001 000056.Pdf (14.29Mb)

POETICAL WORKS OF MATTHEW ARNOLD POETICAL WORKS OF MATTHEW ARNOLD 3Lontion MACMILLAN AND CO. AND NEW YORK I 890 All rights reserved CONTENTS EARLY POEMS SONNETS- PAGE QUIET WORK ..... I To A FRIEND ..... 2 SHAKESPEARE ..... 2 WRITTEN IN EMERSON'S ESSAYS 3 WRITTEN IN BUTLER'S SERMONS 4 To THE DUKE OF WELLINGTON 4 IN HARMONY WITH NATURE . 5 To GEORGE CRUIKSHANK 6 To A REPUBLICAN FRIEND, 1848 6 CONTINUED ..... 7 RELIGIOUS ISOLATION .... 8 MYCERINUS . , , , ' 8 THE CHURCH OF BROU— I. THE CASTLE .... 13 II. THE CHURCH .... 17 III. THE TOMB .... 18 A MODERN SAPPHO .... 20 REQUIESCAT ..... 21 YOUTH AND CALM ..... 22 viii CONTENTS PAGE A ]\IEMORY-PICTURE .... 23 A DREAM ...... 25 THE NEW SIRENS ..... 26 THE VOICE ...... 36 YOUTH'S AGITATIONS . 37 THE WORLD'S TRIUMPHS . = . 38 STAGIRIUS ...... 38 HUMAN LIFE ..... 40 To A GIPSY CHILD BY THE SEA-SHORE . 41 A QUESTION ..... 44 IN UTRUMQUE PARATUS .... 45 THE WORLD AND THE QUIETIST . • . 46 HORATIAN ECHO ..,,,., 47 THE SECOND BEST ...... 49 CONSOLATION ..... 50 RESIGNATION ...... 52 NARRATIVE POEMS SOHRAB AND RUSTUM &5 THE SICK KING IN BOKHARA 92 BALDER DEAD— 1. SENDING lOI 2. JOURNEY TO THE DEAD III 3. FUNERAL 121 TRISTRAM AND ISEULT— 1. TRISTRAM • 138 2. ISEULT OF IRELAND • 150 3. ISEULT OF BRITTANY • 158 CONTENTS IX PAGE SAINT BRANDAN 165 THE NECKAN 167 THE FORSAKEN MERMAN 170 SONNETS AUSTERITY OF POETRY • 177 A PICTURE AT NEWSTEAD 177 RACHEL : i, 11, in • 178 WORLDLY PLACE 180 EAST LONDON 180 WEST LONDON 181 EAST AND WEST 181 THE BETTER PART 182 THE DIVINITY 183 IMMORTALITY 183 THE GOOD SHEPHERD WITH THE KID 184 MONICA'S LAST PRAYER 184 LYRIC POEMS SWITZERLAND— 1. -

Full Discography

DISCOGRAPHY George Schuller | drums (2014) Disc 1: Recorded January 2013, Hudson, NY except (*) recorded May 2013, Firehouse 12 Studio, New Haven, CT. Disc 2: Recorded January 2013, Firehouse 12 20 Studio, New Haven, CT. All Mixed, mastered July - November 2013, Firehouse 12 Studio, New Haven, CT. (CD) Quotes: [★★★1/2] While the 18th-century Armenian troubadour Sayat-Nova may not be a household name in the Western world, he has long been recognized as one of the greatest poets and troubadours to emerge from the Caucasus region. On the two discs that make up Sayat-Nova: Songs Of My Ancestors, the Armenian- American pianist Armen Donelian has prepared a deeply felt—and often strikingly beautiful—tribute to this distant master. Most of Sayat-Nova’s songs survive only as simple melodies, offering considerable scope to the modern RECORDINGS AS LEADER arranger. Donelian - who, in addition to having a long career in jazz, was educated in harmony and Sayat-Nova: Songs Of My counterpoint - has broken his arrangements into two distinct groups: The first disc features solo piano Ancestors versions of nine of Sayat-Nova’s compositions, while (Sunnyside SSC 4018) the second offers four more Sayat-Nova songs (plus 2 CD Set one from Armenian folk musician Khachatur Avetisyan) Disc 1 - Solo Piano performed as a trio with bass and drums. Where Do You Come From, Wandering The solo piano arrangements are, by far, the more Nightingale? (Oosdi Goukas Gharib Blbool?) extraordinary. Although Donelian is respectful of the / I Have Traveled The Whole World Over original melodies, he also appears largely unbound by (Tamam Ashkhar Bdood Eka) Without You, the constraints of any particular musical approach, What Will I Do? (Arantz Kez Eench using the spare frame of Sayat- Nova’s compositions Goneem?) / Surely, You Don't Say That You more as a compass than a map.