John Banville's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Albert Nobbs Notes FINAL 10.8.11 ITA

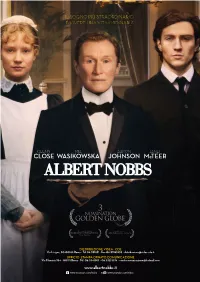

3 NOMINATION GOLDEN GLOBE ® DISTRIBUZIONE VIDEA 5 CDE Via Livigno, 50-00188 Roma - Tel 06.331851 - Fax 06.33185255 - [email protected] UFFICIO STAMPA ORNATO COMUNICAZIONE Via Flaminia 954 - 00191 Roma - Tel. 06.3341017 - 06.33213374 - [email protected] www.albertnobbs.it www.facebook.com/videa www.youtube.com/videa Sinossi La pluripremiata attrice Glenn Close (Albert Nobbs) indossa i panni di una donna coinvolta in un insolito triangolo amoroso. Travestita da uomo per poter lavorare e sopravvivere nell’Irlanda del XIX secolo, più di trent’anni dopo si ritrova prigioniera della sua stessa finzione. Nel prestigioso cast internazionale, Mia Wasikowska (Helen), Aaron Johnson (Joe) e Brendan Gleeson (Dr. Holloran), oltre a Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Janet McTeer, Brenda Fricker e Pauline Collins. Rodrigo Garcia dirige il film basato su un racconto dell’autore irlandese George Moore, adattato da Glenn Close insieme a John Banville, vincitore del premio Man Booker, e a Gabriella Prekop. NOTE DI PRODUZIONE IL LEGAME DI GLENN CLOSE con il personaggio di Albert Nobbs risale a Quasi 30 anni fa, ai tempi in cui recitò – nel 1982 – nella rappresentazione teatrale di Simone Benmussa, ispirata al racconto breve Albert Nobbs, scritto dall’autore irlandese del XIX secolo, George Moore. “Credo che Albert sia un grande personaggio e la storia, in tutta la sua disarmante semplicità, è molto potente dal punto di vista emotivo”, dichiara Close, la cui apparizione in Quella produzione Off-Broadway le valse critiche eccellenti e un Obie Award. Nonostante i grandi successi che Close ha collezionato nel corso della sua brillante carriera, quel personaggio le è rimasto dentro. -

Albert Nobbs

Albert Nobbs Albert Nobbs, ALBERT NOBBS, RODRIGO GARCIA, Golden Globe Award, role, characters, film credits, John Banville, John Boorman, Julie Lynn, starring role, television, Simone Benmussa, Brendan Gleeson, Radha Mitchell, Harry Potter, Aaron Johnson, Los Angeles Film Critics Association, Los Angeles Drama Critics Circle Award, George Roy Hill, Kerry Washington, Margarethe Cammermeyer, Mia Wasikowska, Joe Layton, Directors' Fortnight, Neil Jordan, BBC comedy series, Florida Film Festival, European Film Academy, award nomination, Arlene Kelly, Sweet Emma Dear Bobe, Dublin Theatre Festival, television drama, Michael Cristofer, Franco Zeffirelli, Harvey Goldsmith, Winner Locarno Film Festival, Harold Prince, Irish actor, Fountain House, Andrew Lloyd Webber, Richard Pearce, Norma Desmond, Merchant Ivory, Stephen Frears, Jack Hofsiss, Stephen Herek, Royal National Theatre, Tony Awards, Richard Marquand, Fatal Attraction, Feature Film Commission, Christopher Walken, Barbet Schroeder, Joe, MAIN characters, National Association of Theatre Owners, Andrei Konchalovsky, International Mental Health Research Organization, Monica Rawling, Glenn Jordan, Rose Troche, Panthera Conservation Advisory Committee, Julian Morris, Danny Boyle, JOE Aaron Johnson, British independent film, Kristen Scott Thomas, Golden Globe nomination, Simon Wincer, Colin Farrell, RODRIGO GARCIA GABRIELLA PREKOP JOHN BANVILLE GLENN CLOSE, GLENN CLOSE, Bonnie Curtis, John Travolta, Golden Globe, Michael Vartan, John Lennon, Rhys Meyers, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, London Film Critics, -

The Archaic Shudder? Toward a Poetics of the Sublime (In Two Sections: Creative and Critical)

Title The Archaic Shudder? Toward a poetics of the sublime (in two sections: creative and critical) Student Name Dan Disney Diploma of Arts (Editing), RMIT Bachelor of Arts, Monash University Master of Creative Arts (Research), University of Melbourne This thesis is submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by creative work (50%) and dissertation (50%), School of Culture and Communication, University of Melbourne. Submitted 15th September, 2009. 1 2 Abstract This cross-disciplinary investigation moves toward that sub-genre in aesthetics, the theory of creativity. After introducing my study with a re-reading of Heidegger’s essay, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, I appropriate into a collection of poems ideas from Plato, Kant, Heidegger, Wittgenstein, and a range of post-philosophical theorists. Next, after Murmur and Afterclap, in the critical section of my investigation I formulate a poetics of the sublime, and move closer to my own specialist term, poeticognosis. With this term, I set out to designate a particular style of apprehending-into-language, after wonder, as it pertains (I argue) to creative producers. Section One Murmur and Afterclap The poetry submitted here does not arise simply out of a theoretical position or theoretical concerns, and it is not in any sense exemplary or programmatic. It is, however, related in complex ways to the issues raised later in the critical section of my investigation, and indeed has provoked − necessitated − my theoretical discussion (rather than the other way around). The poems contained in this section of my investigation draw from the many documents I have encountered in my attempt to shape a discourse with philosophy. -

GENRE and CODE in the WORK of JOHN BANVILLE Kevin Boyle

GENRE AND CODE IN THE WORK OF JOHN BANVILLE Kevin Boyle St. Patrick’s College, Drumcondra Dublin City University School of Humanities Department of English Supervisor: Dr Derek Hand A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD April 2016 I hereby certify that this material, which T now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of PhD is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed:_____________________________ ID No.: 59267054_______ Date: Table of contents Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 4 Introduction: Genre and the Intertcxlual aspects of Banville's writing 5 The Problem of Genre 7 Genre Theory 12 Transgenerie Approach 15 Genre and Post-modernity' 17 Chapter One: The Benjamin Black Project: Writing a Writer 25 Embracing Genre Fiction 26 Deflecting Criticism from Oneself to One Self 29 Banville on Black 35 The Crossover Between Pseudonymous Authorial Sell'and Characters 38 The Opposition of Art and Craft 43 Change of Direction 45 Corpus and Continuity 47 Personae Therapy 51 Screen and Page 59 Benjamin Black and Ireland 62 Guilt and Satisfaction 71 Real Individuals in the Black Novels 75 Allusions and Genre Awareness 78 Knowledge and Detecting 82 Chapter Two: Doctor Copernicus, Historical Fiction and Post-modernity: -

1 Introduction 2 Banville's Narcissists

Notes 1 Introduction 1. There is a degree of uniformity to these characters, their situations and their mindsets, that allows us to speak of a typical Banville protagonist with as much legitimacy as we may speak of a typical Beckett or Kafka protagonist. There is an undeniable continuity – much more pronounced than mere fictional family resemblance – between all of Banville’s pro- tagonists, stretching arguably from Nightspawn’s Ben White, but certainly from Freddie Montgomery in The Book of Evidence, to The Sea’s Max Morden. 2. Freud’s first use of the term ‘narcissism’ appears in a footnote added in 1910 to his ‘Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality’, to denote a phase in the development of male homosexuality. His interpretation of the classical myth is, in this sense, quite a literal one. 2 Banville’s Narcissists 1. This article of faith is one which character and creator evidently hold in common. In the essay ‘Making Little Monsters Walk’, Banville delivers the following series of excessively lofty aphoristic paradoxes: ‘Nietzsche was the first to recognize that the true depth of a thing is in its surface. Art is shallow, and therein lies its deeps. The face is all, and, in front of the face, the mask.’ (Banville, 1993c: 108). 2. Kleist and Amphitryon have proven enduring inspirations for Banville. The Infinities is plainly based on the story, and contains a number of meta- fictional allusions not just to the story itself, but to Banville’s own, not particularly successful, stage adaptation of it. One of the novel’s central characters, the actress Helen, is preparing for her role as Amphitryon’s wife Alcemene in the play. -

The Role of Female Characters in the Narrator's Quest for Identity in John

Estudios Irlandeses, Special Issue 13.2, 2018, pp. 44-59 __________________________________________________________________________________________ AEDEI The Role of Female Characters in the Narrator’s Quest for Identity in John Banville’s Eclipse Mar Asensio Aróstegui University of La Rioja, Spain Copyright (c) 2018 by Mar Asensio Aróstegui. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged for access. Abstract. Eclipse is a novel that contributes to John Banville’s idiosyncratic worlds of fiction in presenting the reader with a male narrator who engages in the telling of a journey back to the spatial context of his childhood in an attempt to retrieve what he deems to have lost, his true self. Criticism on the novel has dealt with the narrator’s narcissism, the novel’s narrative style and technique, its modernist/postmodernist allegiance, its intertextual and intermedial nature and its status as trauma narrative. A few attempts have also been made at revisiting the novel from the standpoint of gender, although women have been invariably read as subject to the male gaze, whether as mundane objects of desire or idealized objets d’art. This article aims at showing that women in Eclipse refuse to be mere erotic or artistic objects in a male story. In my view, the narrative centrality of the male figure is progressively challenged by the female characters, both puzzling and fascinating, who stubbornly keep on intruding into the narrator’s solipsistic activities, eventually break free from their usual position as objects of the male gaze and redirect the narrator’s quest and his narrative into an unexpected, moving finale. -

PLATONIC OCCASIONS Dialogues on Literature, Art and Culture Art and Literature, on Dialogues

PLATONIC OCCASIONS Dialogues on Literature, Art and Culture Art and Literature, on Dialogues Richard Begam & James Soderholm Platonic Occasions Dialogues on Literature, Art and Culture Richard Begam & James Soderholm Stockholm English Studies 1 Editorial Board Claudia Egerer, Associate Professor, Department of English, Stockholm University Stefan Helgesson, Professor, Department of English, Stockholm University Nils-Lennart Johannesson, Professor, Department of English, Stockholm University Maria Kuteeva, Professor, Department of English, Stockholm University Published by Stockholm University Press Stockholm University SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden www.stockholmuniversitypress.se Text © Richard Begam, James Soderholm 2015 License CC-BY-NC-ND ORCID: Richard Begam: 0000-0001-5411-8272, James Soderholm: 0000-0003-0477-3636 Supporting Agency (funding): Department of English, Stockholm University First published 2015 Cover Illustration: Wassily Kandinksy, Blue, 1922 Reproduced by permission of the Norton Simon Museum (The Blue Four Galka Scheyer Collection), Pasadena, California Cover designed by Janeen Barker Stockholm English Studies (Online) ISSN: 2002-0163 ISBN (Paperback): 978-91-7635-000-3 ISBN (PDF): 978-91-7635-003-4 ISBN (EPUB): 978-91-7635-002-7 ISBN (Kindle): 978-91-7635-001-0 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.16993/sup.baa This work is licensed under the Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. This license allows the downloading and sharing of the work, providing author attribution is clearly stated. The work cannot be changed in any way and cannot be used for commercial purposes. -

A Few Words for Axel Vander: John Banville and the Pursuit Of

1 A Few Words for Axel Vander: John Banville and the pursuit of deconstruction To read is to understand, to question, to know, to forget, to erase, to deface, to repeat – that is to say, the endless prosopopoeia by which the dead are made to have a face and a voice which tells the allegory of their demise and allows us to apostrophize them in our turn. No degree of knowledge can ever stop this madness, for it is the madness of words.1 When Paul de Man’s wartime journalism in Belgium for the collaborationist paper Le Soir was unearthed in 1987, four years after his death, deconstruction was placed on trial within and beyond the academy. The scandal revolved around legacy, survival and forgetting, and raised questions about how one might speak, or come after, such an event. In the immediate aftermath, Jacques Derrida reflected that the affair had bequeathed “the gift of an ordeal, the summons to a work of reading, historical interpretation, ethico-political reflection, an interminable analysis”.2 For Derrida, those who read after de Man are left with a ceaseless labour of judgement, a reckoning with the past that remains a matter of the present and of the future. Derrida sees de Man’s life and thought as shaped by two separate but entangled temporalities that unsettle notions of ‘before’ and ‘after’: one was a traumatic “prehistoric prelude” in occupied Belgium, the other a “posthistoric afterlife, lighter, less serious” in America. The “war” that de Man endured within himself was lived at “the crossroads of these two incompatible and disjunctive temporalities”. -

Representations of Discourse and of the Feminine in Homer's Odyssey

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, ISSN 2159-5836 December 2013, Vol. 3, No. 12, 757-764 D DAVID PUBLISHING The Shroud and the Trope: Representations of Discourse and of the Feminine in Homer’s Odyssey Alexandre Veloso de Abreu Pontifical Catholic University of Minas Gerais, Minas Gerais, Brazil Understanding that Homer’s Odyssey (1998) has a feminine perspective, this paper intends to explore the Greek epic placing queen Penelope as the protagonist, observing, mainly, the narratological shifts in the story grammar, duration and character elaboration. This study also uses Paul Ricoeur’s The Rule of Metaphor (2008) to analyze the episode of the shroud in Homer’s Odyssey. Ricoeur sees metaphor in three distinct levels: the level of lexis where he bases himself in the works of Aristotle; the level of phrase in which he recurs to the structuralist linguistician Émile Benveniste; and the metaphor in the level of discourse, when Ricoeur himself devises an elaborate study of the figure of speech. Penelope’s weaving can be understood as a representation of discourse and of the feminine. Such analogy transcends the stereotype she is often given and defines a new role for the character in the epic. Keywords: narratology, genre, feminine, Penelope, classical literature Introduction If we acknowledge John Finley’s (1978) explanation in Homer’s Odyssey that “Penelope is the central figure of home; she both kept it in existence and makes it recoverable” and that the main theme of the epic is not the nostos like Aristotle believed but “life brought home, therefore finally shared” (p. 4), we can understand why the same Finley considers that the Odysseia could also be called Penelopeia. -

Images and Banville's Fiction

UCC Library and UCC researchers have made this item openly available. Please let us know how this has helped you. Thanks! Title Beneath the penumbral glow: John Banville and the cinema Author(s) Kirwan, Mark Publication date 2016 Original citation Kirwan, M. 2016. Beneath the penumbral glow: John Banville and the cinema. PhD Thesis, University College Cork. Type of publication Doctoral thesis Rights © 2016, Mark Kirwan. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Embargo information No embargo required Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/4186 from Downloaded on 2021-10-01T15:09:21Z 1 Beneath the Penumbral Glow: John Banville and the Cinema Mark Kirwan DISSERTATION SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY TO THE NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND, UNIVERSITY COLLEGE CORK. RESEARCH CONDUCTED IN THE SCHOOL OF ENGLISH, UNIVERSITY COLLEGE CORK, UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROFESSOR GRAHAM ALLEN AND PROFESSOR ALEX DAVIS JANUARY 2016 HEAD OF SCHOOL: PROFESSOR CLAIRE CONNOLLY 2 Abstract This study focuses on the cinematic aspects of John Banville’s work, aiming to answer how the overt cinematic interest in the cinema in his later work is to be understood in the context of his writing career as a whole. His writing plays on the difficulties inherent in the relationship between appearances and reality, raising questions about how words and images, accurately or otherwise, represent the world. The thesis here is that the cinema has become a significant feature and powerful symbolic image of these preoccupations in the later period of Banville’s career, resonating with his earlier work while bringing a new frame through which to look at his novels and wider career. -

The Odyssey by Homer Book 1

The Odyssey by Homer Book 1 (translated text) [1] Tell me, O Muse, of the man of many devices, who wandered full many ways after he had sacked the sacred citadel of Troy. Many were the men whose cities he saw and whose mind he learned, aye, and many the woes he suffered in his heart upon the sea, seeking to win his own life and the return of his comrades. Yet even so he saved not his comrades, though he desired it sore, for through their own blind folly they perished—fools, who devoured the kine of Helios Hyperion; but he took from them the day of their returning. Of these things, goddess, daughter of Zeus, beginning where thou wilt, tell thou even unto us. [11] Now all the rest, as many as had escaped sheer destruction, were at home, safe from both war and sea, but Odysseus alone, filled with longing for his return and for his wife, did the queenly nymph Calypso, that bright goddess, keep back in her hollow caves, yearning that he should be her husband. But when, as the seasons revolved, the year came in which the gods had ordained that he should return home to Ithaca, not even there was he free from toils, even among his own folk. And all the gods pitied him save Poseidon; but he continued to rage unceasingly against godlike Odysseus until at length he reached his own land. Howbeit Poseidon had gone among the far-off Ethiopians—the Ethiopians who dwell sundered in twain, the farthermost of men, some where Hyperion sets and some where he rises, there to receive a hecatomb of bulls and rams, and there he was taking his joy, sitting at the feast; but the other gods were gathered together in the halls of Olympian Zeus. -

Elm Grove Public Library Adult Movies and TV on DVD

Elm Grove Public Library Adult Movies and TV on DVD A.I. Artificial intelligence After the funeral The Abbott and Costello show. Season two Appointment with death Abduction Cards on the table About a boy Death in the clouds About Schmidt Death on the Nile About time Evil under the sun Abraham Lincoln, vampire hunter Five little pigs Absolute power Hickory dickory dock The abyss The Hollow The accidental husband Lord Edgware dies The accidental tourist Murder in Mesopotamia The accountant The murder of Roger Ackroyd Billy Wilder's Ace in the hole Murder on the links Across the universe Murder on the Orient Express Act of will Mystery of the Blue Train Acts of violence Peril at End House Adam Bede Poirot. Series 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 12,13 The Adams chronicles Poirot : the movie collection. Set 3 & 4 Adam's rib Poirot collector’s set 5 Adaptation Sad cypress The Adjustment Bureau Taken at the flood Admission Third girl Adrift Agatha Christie's Tommy & Tuppence partners in crime. The adventures of Ozzie & Harriet. Christmas with the Nelsons Set 1 & Set 2 The adventures of Robin Hood (1937) Agatha Christie’s Why didn't they ask Evans? The adventures of Robin Hood. The complete first season The little murders of Agatha Christie = Les petits Affair in Trinidad meurtres d'Agatha Christie. Set 1 An affair to remember Agatha Raisin. Series one Affairs of the heart. Series 1, 2 The age of Adaline Affliction Age of heroes The African Queen The age of innocence After Earth The agony and the ecstasy After the thin man Airport Agatha Christie, a life in pictures Airplane The Agatha Christie hour.