Representations of Discourse and of the Feminine in Homer's Odyssey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Odyssey Glossary of Names

GLOSSARY OF NAMES GLOSSARY OF NAMES [Note, the following is raw output from OCR software, and is otherwise unedited.] (First appearance noted by book and line number.) Achaeans (A-kee'-unz): General term used by Homer to reFer to Greeks. 2.139 Acheron (A'-ker-on): River in the Underworld, land of the dead. 10.537 Achilles (A-kil'-eez): Son of Peleus and Thetis. He is the heroic leader of the Myrmidons in the Trojan War and is slain by Paris. Odysseus consults him in the Underworld. 3.117 Aeaea (Ee-ee'-a): Island on which Circe lives. 9.34 Aegisthus (Ee-jis'-thus): Son of Thyestes and Pelopia. He seduces Clytemnestra, wife of Agamemnon, while Agamemnon is away fighting the Trojan War and helps her slay Agamemnon when he returns. Orestes avenges this action years later by murdering both Clytemnestra and Aegisthus. 1.35 GLOSSARY OF NAMES Aegyptus (Ee-jip'-tus): The Nile River. 4.511 Aeolus (Ee'-oh-lus): King of the island Aeolia and keeper of the winds. 10.2 Aeson (Ee'-son): Son oF Cretheus and Tyro; father of Jason, leader oF the Argonauts. 11.262 Aethon (Ee'-thon): One oF Odysseus' aliases used in his conversation with Penelope. 19.199 Agamemnon (A-ga-mem'-non): Son oF Atreus and Aerope; brother of Menelaus; husband oF Clytemnestra. He commands the Greek Forces in the Trojan War. He is killed by his wiFe and her lover when he returns home; his son, Orestes, avenges this murder. 1.36 Agelaus (A-je-lay'-us): One oF Penelope's suitors; son oF Damastor; killed by Odysseus. -

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth)

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth) Uranus (Heaven) Oceanus = Tethys Iapetus (Titan) = Clymene Themis Atlas Menoetius Prometheus Epimetheus = Pandora Prometheus • “Prometheus made humans out of earth and water, and he also gave them fire…” (Apollodorus Library 1.7.1) • … “and scatter-brained Epimetheus from the first was a mischief to men who eat bread; for it was he who first took of Zeus the woman, the maiden whom he had formed” (Hesiod Theogony ca. 509) Prometheus and Zeus • Zeus concealed the secret of life • Trick of the meat and fat • Zeus concealed fire • Prometheus stole it and gave it to man • Freidrich H. Fuger, 1751 - 1818 • Zeus ordered the creation of Pandora • Zeus chained Prometheus to a mountain • The accounts here are many and confused Maxfield Parish Prometheus 1919 Prometheus Chained Dirck van Baburen 1594 - 1624 Prometheus Nicolas-Sébastien Adam 1705 - 1778 Frankenstein: The Modern Prometheus • Novel by Mary Shelly • First published in 1818. • The first true Science Fiction novel • Victor Frankenstein is Prometheus • As with the story of Prometheus, the novel asks about cause and effect, and about responsibility. • Is man accountable for his creations? • Is God? • Are there moral, ethical constraints on man’s creative urges? Mary Shelly • “I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world” (Introduction to the 1831 edition) Did I request thee, from my clay To mould me man? Did I solicit thee From darkness to promote me? John Milton, Paradise Lost 10. -

Mecoptera: Meropeidae): Simply Dull Or Just Inscrutable?

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Insecta Mundi Florida 8-24-2007 Etymology of the earwigfly, Merope tuber Newman (Mecoptera: Meropeidae): Simply dull or just inscrutable? Louis A. Somma University of Florida, [email protected] James C. Dunford University of Florida, Gainesville, FL Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi Part of the Entomology Commons Somma, Louis A. and Dunford, James C., "Etymology of the earwigfly, Merope tuber Newman (Mecoptera: Meropeidae): Simply dull or just inscrutable?" (2007). Insecta Mundi. 65. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi/65 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Florida at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Insecta Mundi by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. INSECTA MUNDI A Journal of World Insect Systematics 0013 Etymology of the earwigfly, Merope tuber Newman (Mecoptera: Meropeidae): Simply dull or just inscrutable? Louis A. Somma Department of Zoology PO Box 118525 University of Florida Gainesville, FL 32611-8525 [email protected] James C. Dunford Department of Entomology and Nematology PO Box 110620, IFAS University of Florida Gainesville, FL 32611-0620 [email protected] Date of Issue: August 24, 2007 CENTER FOR SYSTEMATIC ENTOMOLOGY, INC., Gainesville, FL Louis A. Somma and James C. Dunford Etymology of the earwigfly, Merope tuber Newman (Mecoptera: Meropeidae): Simply dull or just inscrutable? Insecta Mundi 0013: 1-5 Published in 2007 by Center for Systematic Entomology, Inc. P. O. Box 147100 Gainesville, FL 32604-7100 U. -

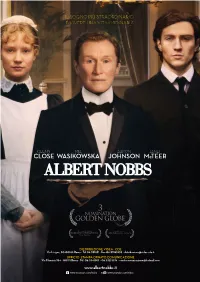

Albert Nobbs Notes FINAL 10.8.11 ITA

3 NOMINATION GOLDEN GLOBE ® DISTRIBUZIONE VIDEA 5 CDE Via Livigno, 50-00188 Roma - Tel 06.331851 - Fax 06.33185255 - [email protected] UFFICIO STAMPA ORNATO COMUNICAZIONE Via Flaminia 954 - 00191 Roma - Tel. 06.3341017 - 06.33213374 - [email protected] www.albertnobbs.it www.facebook.com/videa www.youtube.com/videa Sinossi La pluripremiata attrice Glenn Close (Albert Nobbs) indossa i panni di una donna coinvolta in un insolito triangolo amoroso. Travestita da uomo per poter lavorare e sopravvivere nell’Irlanda del XIX secolo, più di trent’anni dopo si ritrova prigioniera della sua stessa finzione. Nel prestigioso cast internazionale, Mia Wasikowska (Helen), Aaron Johnson (Joe) e Brendan Gleeson (Dr. Holloran), oltre a Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Janet McTeer, Brenda Fricker e Pauline Collins. Rodrigo Garcia dirige il film basato su un racconto dell’autore irlandese George Moore, adattato da Glenn Close insieme a John Banville, vincitore del premio Man Booker, e a Gabriella Prekop. NOTE DI PRODUZIONE IL LEGAME DI GLENN CLOSE con il personaggio di Albert Nobbs risale a Quasi 30 anni fa, ai tempi in cui recitò – nel 1982 – nella rappresentazione teatrale di Simone Benmussa, ispirata al racconto breve Albert Nobbs, scritto dall’autore irlandese del XIX secolo, George Moore. “Credo che Albert sia un grande personaggio e la storia, in tutta la sua disarmante semplicità, è molto potente dal punto di vista emotivo”, dichiara Close, la cui apparizione in Quella produzione Off-Broadway le valse critiche eccellenti e un Obie Award. Nonostante i grandi successi che Close ha collezionato nel corso della sua brillante carriera, quel personaggio le è rimasto dentro. -

Albert Nobbs

Albert Nobbs Albert Nobbs, ALBERT NOBBS, RODRIGO GARCIA, Golden Globe Award, role, characters, film credits, John Banville, John Boorman, Julie Lynn, starring role, television, Simone Benmussa, Brendan Gleeson, Radha Mitchell, Harry Potter, Aaron Johnson, Los Angeles Film Critics Association, Los Angeles Drama Critics Circle Award, George Roy Hill, Kerry Washington, Margarethe Cammermeyer, Mia Wasikowska, Joe Layton, Directors' Fortnight, Neil Jordan, BBC comedy series, Florida Film Festival, European Film Academy, award nomination, Arlene Kelly, Sweet Emma Dear Bobe, Dublin Theatre Festival, television drama, Michael Cristofer, Franco Zeffirelli, Harvey Goldsmith, Winner Locarno Film Festival, Harold Prince, Irish actor, Fountain House, Andrew Lloyd Webber, Richard Pearce, Norma Desmond, Merchant Ivory, Stephen Frears, Jack Hofsiss, Stephen Herek, Royal National Theatre, Tony Awards, Richard Marquand, Fatal Attraction, Feature Film Commission, Christopher Walken, Barbet Schroeder, Joe, MAIN characters, National Association of Theatre Owners, Andrei Konchalovsky, International Mental Health Research Organization, Monica Rawling, Glenn Jordan, Rose Troche, Panthera Conservation Advisory Committee, Julian Morris, Danny Boyle, JOE Aaron Johnson, British independent film, Kristen Scott Thomas, Golden Globe nomination, Simon Wincer, Colin Farrell, RODRIGO GARCIA GABRIELLA PREKOP JOHN BANVILLE GLENN CLOSE, GLENN CLOSE, Bonnie Curtis, John Travolta, Golden Globe, Michael Vartan, John Lennon, Rhys Meyers, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, London Film Critics, -

The Archaic Shudder? Toward a Poetics of the Sublime (In Two Sections: Creative and Critical)

Title The Archaic Shudder? Toward a poetics of the sublime (in two sections: creative and critical) Student Name Dan Disney Diploma of Arts (Editing), RMIT Bachelor of Arts, Monash University Master of Creative Arts (Research), University of Melbourne This thesis is submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by creative work (50%) and dissertation (50%), School of Culture and Communication, University of Melbourne. Submitted 15th September, 2009. 1 2 Abstract This cross-disciplinary investigation moves toward that sub-genre in aesthetics, the theory of creativity. After introducing my study with a re-reading of Heidegger’s essay, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, I appropriate into a collection of poems ideas from Plato, Kant, Heidegger, Wittgenstein, and a range of post-philosophical theorists. Next, after Murmur and Afterclap, in the critical section of my investigation I formulate a poetics of the sublime, and move closer to my own specialist term, poeticognosis. With this term, I set out to designate a particular style of apprehending-into-language, after wonder, as it pertains (I argue) to creative producers. Section One Murmur and Afterclap The poetry submitted here does not arise simply out of a theoretical position or theoretical concerns, and it is not in any sense exemplary or programmatic. It is, however, related in complex ways to the issues raised later in the critical section of my investigation, and indeed has provoked − necessitated − my theoretical discussion (rather than the other way around). The poems contained in this section of my investigation draw from the many documents I have encountered in my attempt to shape a discourse with philosophy. -

John Banville's

Études irlandaises 43-2 | 2018 Varia John Banville’s “Overman”: Intertextual dialogues with Friedrich Nietzsche in Shroud Mehdi Ghassemi Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/etudesirlandaises/5826 DOI: 10.4000/etudesirlandaises.5826 ISSN: 2259-8863 Publisher Presses universitaires de Caen Printed version Date of publication: 18 December 2018 Number of pages: 159-181 ISBN: 978-2-7535-7693-3 ISSN: 0183-973X Electronic reference Mehdi Ghassemi, « John Banville’s “Overman”: Intertextual dialogues with Friedrich Nietzsche in Shroud », Études irlandaises [Online], 43-2 | 2018, Online since 01 November 2018, connection on 22 September 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/etudesirlandaises/5826 ; DOI : 10.4000/ etudesirlandaises.5826 © Presses universitaires de Rennes John Banville’s “Overman”: Intertextual dialogues with Friedrich Nietzsche in Shroud Mehdi Ghassemi Université de Lille Résumé Cet article propose de lire Shroud (2003) de John Banville comme exemple qui illustre le mieux le dialogue de l’écrivain avec la philosophie de Friedrich Nietzsche. Cette étude tente de retracer les manières dont le narrateur incorpore et ensuite réinvente la notion Nietzschéenne de l’homme (Übermensch) à travers de ses métaphores élaborées. Ce projet soutient également que c’est bien Nietzsche qui fournit finalement au narrateur banvillean l’outil nécessaire pour encadrer une conception du “moi” qui serait immune à la crise linguistique proposée par la déconstruction. Mots clés: Banville, Shroud, Nietzsche, authenticité, déconstruction Abstract This paper proposes to read John Banville’s Shroud (2003) as an example that most aptly illus- trates the writer’s dialogue with the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche. It traces the ways in which Banville’s narrator incorporates Nietzsche’s conception of self and demonstrates how Banville rein- vents Nietzsche’s idea of the Overman through elaborate metaphors. -

Virginia Woolf's Novels and the Literary Past

Virginia Woolf’s Novels and the Literary Past Jane de Gay Edinburgh University Press © Jane de Gay, 2006 Edinburgh University Press Ltd 22 George Square, Edinburgh Typeset in 10.5/13 Adobe Sabon by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Manchester, and printed and bound in Great Britain by The Cromwell Press, Trowbridge, Wilts A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0 7486 2349 3 (hardback) The right of Jane de Gay to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Contents Acknowledgements v Abbreviations vii Introduction 1 1. From Woman Reader to Woman Writer: The Voyage Out 19 2. Tradition and Exploration in Night and Day 44 3. Literature and Survival: Jacob’s Room and Mrs Dalloway 67 4. To the Lighthouse and the Ghost of Leslie Stephen 96 5. Rewriting Literary History in Orlando 132 6. ‘Lives Together’: Literary and Spiritual Autobiographies in The Waves 160 7. Bringing the Literary Past to Life in Between the Acts 186 Conclusion 212 Select Bibliography 216 Index 227 Acknowledgements Quotations from Virginia Woolf’s novels by permission of The Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of Virginia Woolf. Excerpts from Night and Day, copyright 1920 by George H. Doran and Company and renewed 1948 by Leonard Woolf, reprinted by permission of Harcourt, Inc. Excerpts from To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf, copyright 1927 by Harcourt, Inc. and renewed 1954 by Leonard Woolf, reprinted by permission of the publisher. Excerpts from Orlando copy- right 1928 by Virginia Woolf and renewed 1956 by Leonard Woolf, reprinted by permission of Harcourt, Inc. -

Divine Riddles: a Sourcebook for Greek and Roman Mythology March, 2014

Divine Riddles: A Sourcebook for Greek and Roman Mythology March, 2014 E. Edward Garvin, Editor What follows is a collection of excerpts from Greek literary sources in translation. The intent is to give students an overview of Greek mythology as expressed by the Greeks themselves. But any such collection is inherently flawed: the process of selection and abridgement produces a falsehood because both the narrative and meta-narrative are destroyed when the continuity of the composition is interrupted. Nevertheless, this seems the most expedient way to expose students to a wide range of primary source information. I have tried to keep my voice out of it as much as possible and will intervene as editor (in this Times New Roman font) only to give background or exegesis to the text. All of the texts in Goudy Old Style are excerpts from Greek or Latin texts (primary sources) that have been translated into English. Ancient Texts In the field of Classics, we refer to texts by Author, name of the book, book number, chapter number and line number.1 Every text, regardless of language, uses the same numbering system. Homer’s Iliad, for example, is divided into 24 books and the lines in each book are numbered. Hesiod’s Theogony is much shorter so no book divisions are necessary but the lines are numbered. Below is an example from Homer’s Iliad, Book One, showing the English translation on the left and the Greek original on the right. When citing this text we might say that Achilles is first mentioned by Homer in Iliad 1.7 (i.7 is also acceptable). -

Greek Mythology Link (Complete Collection)

Document belonging to the Greek Mythology Link, a web site created by Carlos Parada, author of Genealogical Guide to Greek Mythology Characters • Places • Topics • Images • Bibliography • Español • PDF Editions About • Copyright © 1997 Carlos Parada and Maicar Förlag. This PDF contains portions of the Greek Mythology Link COMPLETE COLLECTION, version 0906. In this sample most links will not work. THE COMPLETE GREEK MYTHOLOGY LINK COLLECTION (digital edition) includes: 1. Two fully linked, bookmarked, and easy to print PDF files (1809 A4 pages), including: a. The full version of the Genealogical Guide (not on line) and every page-numbered docu- ment detailed in the Contents. b. 119 Charts (genealogical and contextual) and 5 Maps. 2. Thousands of images organized in albums are included in this package. The contents of this sample is copyright © 1997 Carlos Parada and Maicar Förlag. To buy this collection, visit Editions. Greek Mythology Link Contents The Greek Mythology Link is a collection of myths retold by Carlos Parada, author of Genealogical Guide to Greek Mythology, published in 1993 (available at Amazon). The mythical accounts are based exclusively on ancient sources. Address: www.maicar.com About, Email. Copyright © 1997 Carlos Parada and Maicar Förlag. ISBN 978-91-976473-9-7 Contents VIII Divinities 1476 Major Divinities 1477 Page Immortals 1480 I Abbreviations 2 Other deities 1486 II Dictionaries 4 IX Miscellanea Genealogical Guide (6520 entries) 5 Three Main Ancestors 1489 Geographical Reference (1184) 500 Robe & Necklace of -

O Oceanids (Ὠκεανίδες). the 'Holy Company' of Daughters of *Ocean and *Tethys, and Sisters of the River-Gods. Their N

O Oceanids (Ὠκεανίδες). The 'holy company' of daughters of *Ocean and *Tethys, and sisters of the river-gods. Their number varies, but Apollodorus names seven (Asia, *Styx, Electra, Doris, Eurynome, *Amphitrite, *Metis) and Hesiod forty-one, including, in addition to those mentioned by Apollodorus, *Calypso *Clymene and Philyra. Most of those named mated with gods (Amphitrite with Poseidon, Doris with Nereus for example) and produced important offspring (Athena was born from Metis and Zeus, Philyra mated with Kronos in the form of a horse and produced the centaur Chiron, Clymene was the mother of Prometheus, and also bore Phaethon to Helius the sun-god.). The sons of Ocean were the fresh-water rivers, but some of the daughters were sea-nymphs, others spirits of streams called after a characteristic of their water such as Ocyrrhoe ('swift-flowing') or Xanthe ('brownish-yellow'); Styx, unusually, was a female river deity, personifying the river of Hades. Calypso ruled over the island kingdom of Ogygia (but her parentage as a true Oceanid is disputed). Metis had the ability, common to sea-gods, of being able to change her shape, although she was little more than the personification of wisdom, swallowed by Zeus in order to absorb that wisdom and to contain any threat from the child with whom she was pregnant. Oceanids feature as the chorus in Prometheus Bound, a tragedy which is set at the north-eastern edge of the known world, and at a time before Zeus had consolidated his power. The Oceanids were part of the older, pre-Olympian race of gods, who had a role as consorts or mothers of other divinities, but were more often viewed anonymously as belonging to the vastness of the sea, to be placated in times of storm and turbulence. -

Z Zacynthus (Ζάκυνθος). Son of Dardanus; the Eponym and First

Z Zacynthus (Ζάκυνθος). Son of Dardanus; the eponym and first ruler of Zacynthus (now Zante), a large island off the north-west Peloponnese. He left his native city of Psophis in Arcadia to colonise the island. [Pausanias 8.54] Zagreus (Ζαγρεύς). See Dionysus. Zelus (Ζῆλος). Son of Pallas and Styx; the personification of Emulation. With the other children of *Styx, he helped Zeus in his war against the Titans, and, with his siblings Nike ('victory'), Kratos ('strength') and Bia ('violence') lived with him ever afterwards (i.e. they became his attributes). [Apollodorus 1.9; Hesiod Theog 383-403] Zephyr (Ζέφυρος). Son of Astraeus and Eos, the 'strong-hearted' West Wind personified, which in Greece is a healthy and cleansing wind. Xanthus and Balius, the horses of Achilles were offspring of Zephyr by Podarge, a Harpy. In the Iliad, Iris visited him in his house in Thrace, where he was feasting with the other winds, to report that Achilles had promised offerings to him and *Boreas if they would blow to kindle the pyre of Patroclus. According to a late tradition, he competed with Apollo for the love of *Hyacinthus. [Hesiod Theog 379; Homer Il 16.149-51; Pausanias 3.19.5] Zetes (Ζήτης). See Boreads. Zethus (Ζῆθος). Son of Zeus and Antiope. He and his twin brother Amphion were exposed at birth, but they were rescued and later became joint kings of Thebes. Zethus devoted himself to practical pursuits such as cattle-breeding, in contrast to his brother who was a great musician. He married Aedon, daughter of Pandareus, who bore him a son Itylus.