University of Nevada, Reno Text and Image in Ulrich Molitor's De Lamiis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2210 Bc 2200 Bc 2190 Bc 2180 Bc 2170 Bc 2160 Bc 2150 Bc 2140 Bc 2130 Bc 2120 Bc 2110 Bc 2100 Bc 2090 Bc

2210 BC 2200 BC 2190 BC 2180 BC 2170 BC 2160 BC 2150 BC 2140 BC 2130 BC 2120 BC 2110 BC 2100 BC 2090 BC Fertile Crescent Igigi (2) Ur-Nammu Shulgi 2192-2190BC Dudu (20) Shar-kali-sharri Shu-Turul (14) 3rd Kingdom of 2112-2095BC (17) 2094-2047BC (47) 2189-2169BC 2217-2193BC (24) 2168-2154BC Ur 2112-2004BC Kingdom Of Akkad 2234-2154BC ( ) (2) Nanijum, Imi, Elulu Imta (3) 2117-2115BC 2190-2189BC (1) Ibranum (1) 2180-2177BC Inimabakesh (5) Ibate (3) Kurum (1) 2127-2124BC 2113-2112BC Inkishu (6) Shulme (6) 2153-2148BC Iarlagab (15) 2121-2120BC Puzur-Sin (7) Iarlaganda ( )(7) Kingdom Of Gutium 2177-2171BC 2165-2159BC 2142-2127BC 2110-2103BC 2103-2096BC (7) 2096-2089BC 2180-2089BC Nikillagah (6) Elulumesh (5) Igeshaush (6) 2171-2165BC 2159-2153BC 2148-2142BC Iarlagash (3) Irarum (2) Hablum (2) 2124-2121BC 2115-2113BC 2112-2110BC ( ) (3) Cainan 2610-2150BC (460 years) 2120-2117BC Shelah 2480-2047BC (403 years) Eber 2450-2020BC (430 years) Peleg 2416-2177BC (209 years) Reu 2386-2147BC (207 years) Serug 2354-2124BC (200 years) Nahor 2324-2176BC (199 years) Terah 2295-2090BC (205 years) Abraham 2165-1990BC (175) Genesis (Moses) 1)Neferkare, 2)Neferkare Neby, Neferkamin Anu (2) 3)Djedkare Shemay, 4)Neferkare 2169-2167BC 1)Meryhathor, 2)Neferkare, 3)Wahkare Achthoes III, 4)Marykare, 5)............. (All Dates Unknown) Khendu, 5)Meryenhor, 6)Neferkamin, Kakare Ibi (4) 7)Nykare, 8)Neferkare Tereru, 2167-2163 9)Neferkahor Neferkare (2) 10TH Dynasty (90) 2130-2040BC Merenre Antyemsaf II (All Dates Unknown) 2163-2161BC 1)Meryibre Achthoes I, 2)............., 3)Neferkare, 2184-2183BC (1) 4)Meryibre Achthoes II, 5)Setut, 6)............., Menkare Nitocris Neferkauhor (1) Wadjkare Pepysonbe 7)Mery-........, 8)Shed-........, 9)............., 2183-2181BC (2) 2161-2160BC Inyotef II (-1) 2173-2169BC (4) 10)............., 11)............., 12)User...... -

The Babylonian Expedition of the University of Pennsylvania

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 3 1924 085 210 981 Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924085210981 THE BABYLONIAN EXPEDITION OP THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA SERIES D: RESEARCHES AND TREATISES EDITED BY H. V. HILPEECHT VOLUME III BY HERMANN RANKE " Eckley Brinton Coxe, Junior, Fund " PHILADELPHIA v Published by the University of Pennsylvania 1905 Philadelphia : MacCalla & Co. Inc., Painters Early Babylonian Personal Names THE PUBLISHED TABLETS OP THE SO-CALLED HAMMURABI DYNASTY (B.C. 2000) BY HERMANN EANKE, Ph.D. Formerly Harrison Research Fellow in Assyriology, University of Pennsylvania PHILADELPHIA 19 05 TO MY HIGHLY ESTEEMED TEACHER AND FRIEND Dr. FKITZ HOMMEL Professor of Semitic Philology at the University of Munich PREFACE. THE material for the name list here published formed the basis of my dissertation " Die Personennamen in den Urkunden der Hammurdbi-Dynastie," published in Munich, summer of 1902. A considerable portion of the two years that have since elapsed has been devoted to a thorough reinvestigation of all the material, and this has resulted in a number of corrections in the readings as well as in the interpretation of some of the names. At the same time the material has been restricted : all names from documents of question- able date have been excluded from the list. This enables us to discuss the problems involved with more certainty. Names taken from undated documents which, however, for palaeographical and other reasons, belong to the period of the first dynasty of Babylon, have been used for comparison in the notes referring to the name-elements. -

Bible Studies: Balaam Oracles

BIBLE STUDIES. By M. M. KALISCH, PH. D., M.A. PART 1. THE PROPHECIES OF BALAAM (NUMBERS XXII. to XXIV) OR THE HEBREW AND THE HEATHEN. LONDON: LONGMANS, GREEN AND CO. 1877 Public Domain Digitized by Ted Hildebrandt 2004 PREFACE. ALMOST immediately after the completion of the fourth volume of his Commentary on the Old Testament, in 1872, the author was seized with a severe and lingering illness. The keen pain he felt at the compulsory interrup- tion of his work was solely relieved by the undiminished interest with which he was able to follow the widely ram- ified literature connected with his favourite studies. At length, after weary years of patience and ‘hope deferred,’ a moderate measure of strength seemed to return, inadequate indeed to a resumption of his principal task in its full ex- tent, yet, sufficient, it appeared, to warrant, an attempt at elucidating some of those, numerous problems of Biblical criticism and religious history, which are still awaiting a final solution. Acting, therefore, on the maxim, ‘Est quadam prodire tenus, si non datur ultra,’ and stim- lated by the desire of contributing his humble share to the great intellectual labour of our age, he selected, as a first effort after his partial recovery, the interpretation of that exquisite episode in the Book of Numbers which contains an account of Balaam and his prophecies. This section), complete in itself, discloses a deep insight into the nature and course of prophetic influence; implies most instructive hints for the knowledge of Hebrew doctrine; and is one of the choicest, master-pieces of universal literature. -

Policy of Fear: Phenomenon of Witch Hunt in Early Modern Europe

BRATISLAVA INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL OF LIBERAL ARTS Bachelor Thesis Policy of Fear: Phenomenon of Witch Hunt in Early Modern Europe Alexandra Ballová 2013/ 2014 BRATISLAVA INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL OF LIBERAL ARTS Bachelor Thesis The Policy of Fear: Phenomenon of Witch Hunt in Early Modern Europe Study Program: Liberal Arts Field of Study: 3. 1. 6. Political Science Thesis Advisor: prof. PhDr. František Novosád, CSc. Degree to be awarded: Bachelor (abbr. “Bc.”) Handed in: 30. 4. 2014 Date of Defense: 11. 6. 2014 Alexandra Ballová Bratislava, 2014 Declaration of Originality I declare that this Thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in part or in whole elsewhere. All used literature and other sources are attributed and properly cited in references. Bratislava 22. 4. 2014 Alexandra Ballová ii Abstrakt Názov práce: Policy of Fear: Phenomenon of Witch Hunt in Early Modern Europe Autor práce: Alexandra Ballová Vysoká škola: Bratislavská medzinárodná škola liberálnych štúdií Meno školiteľa: prof. PhDr. FrantišekNovosád, CSc. Komisia pre obhajoby: doc. Samuel Abrahám, PhD., Prof. PhDr. František Novosád, CSc., Mgr. Dagmar Kusá, PhD. Predseda komisie: doc. Samuel Abrahám, PhD. Kľúčové pojmy: skoro moderné obdobie, lov na čarodejnice, sociológia, strach, cirkev Cieľom tejto práce nie je posúdiť morálny význam honov na čarodejnice, ktoré sa masovo rozmohli najmä v období 13. až 17. storočia. Napriek dobe, ktorá ubehla od posledného veľkolepého autodafé je upaľovanie čarodejníc stále kontroverznou témou, ktorá stavia ľudí na rôzne strany. Nie je známe ani presné číslo obetí týchto honov, ich počet sa mení podľa toho, kto sa tejto téme zrovna venuje. Avšak existenciu týchto honov nie je možné poprieť a dodnes je možné vidieť miesta, kde sa konali. -

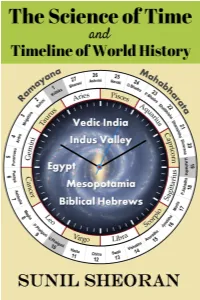

The Science of Time and Timeline of World History (Sunil Sheoran, 2017).Pdf

The Science of Time and Timeline of World History The Science of Time and Timeline of World History SUNIL SHEORAN eBook Edition v.1.0.0.1 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Sunil Sheoran All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written permission of the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. However, this book is available to download for free in PDF format as an eBook that may not be reverse- engineered or copied, printed and sold for any commercial gains. But it may be printed for personal and non-commercial educational use in its original form, without any modification to its contents or structure. First English Edition 2017 (eBook v.1.0.0.1) Price: –0.00/– Sunil Sheoran Bhiwani, Haryana India - 127021 TheScienceOfTime.com Facebook: fb.com/thescienceoftime Twitter: twitter.com/Science_of_Time Email: tsotbook [at] gmail.com Prayer नमकृ तं महादवे ं िशवं सयं योगेरम् । I salute the great god Śiva, embodiment of truth & ultimate Yogī. नमकृ तं उमादवे महामाया महकारणम् ॥ 1 I salute Umā, the great illusory power & first principle of creation. नमकृ तं दवनायके ं पावकं मयूरवािहनम् । I salute the general of gods, the fiery one who rides a peacock. नमकृ तं अदवे ं सुमुखं ासायलेखकम् ॥ 2 I salute the first-worshipped, of beautiful face & the writer of Vyāsa. -

Witch Trials*

The Economic Journal, 128 (August), 2066–2105. Doi: 10.1111/ecoj.12498 © 2017 Royal Economic Society. Published by John Wiley & Sons, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA. WITCH TRIALS* Peter T. Leeson and Jacob W. Russ We argue that the great age of European witch trials reflected non-price competition between the Catholic and Protestant churches for religious market share in confessionally contested parts of Christendom. Analyses of new data covering more than 43,000 people tried for witchcraft across 21 European countries over a period of five-and-a-half centuries and more than 400 early modern European Catholic–Protestant conflicts support our theory. More intense religious-market contes- tation led to more intense witch-trial activity. And compared to religious-market contestation, the factors that existing hypotheses claim were important for witch-trial activity – weather, income and state capacity – were not. For, where God built a church there the Devil would also build a chapel. –Martin Luther (Kepler, 2005, p. 23) Witch trials have a peculiar history in Christendom. Between 900 and 1400, Christian authorities were unwilling to so much as admit that witches existed, let alone try someone for the crime of being one. This was not for lack of demand. Belief in witches was common in medieval Europe and in 1258 Pope Alexander IV had to issue a canon to prevent prosecutions for witchcraft (Kors and Peters, 2001, p. 117). By 1550, Christian authorities had reversed their position entirely. Witches now existed in droves and, to protect citizens against the perilous threat witchcraft posed to their safety and well-being, had to be prosecuted and punished wherever they were found.1 In the wake of this reversal, a literal witch-hunt ensued across Christendom. -

4 Califas Daeshitas)

LISTADO DE LOS 102 CALIFAS DAESHITAS Los cuatro primeros califas daeshitas (4 califas daeshitas) 1. Sulili (Fundador de la Casa Real Asira o daeshita) 2. Kikkia 3. Akiya 4. Zariqum, (c. 2040 a. C.) no figura en la Lista real asiria, pero está atestiguado arqueológicamente como gobernador de Assur. Dinastía de Puzur-Ashur (9 califas daeshitas) 1. Puzur-Ashur I (c. 2003 a. C.-1975 a. C.) 2. Shalim-akhe (hacia 1950 a. C.) 3. Ilushuma (c. 1915 a. C.-1890 a. C.) 4. Erishum I (c. 1890 a. C.-1851 a. C.) 5. Ikunum (hacia 1850 a. C.) 6. Sargón I (hacia 1845 a. C.) (no confundir con Sargón de Akkad) 7. Puzur-Ashur II (hacia 1840 a. C.) 8. Naram-Sin (1830 a. C.-1818 a. C.) 9. Erishum II (1818 a. C.-1813 a. C.) Dinastía amorrea o de Shamshiadad I (5 califas daeshitas) 1. Shamshiadad I (1813-1781 a. C.) 2. Ishme-Dagan I (1780-1741 a. C.) 3. Mut-ashkur (c.1740-1730 a. C.) 4. Rimush (c.1730-1727 a. C.) 5. Asinum (c.1726 a. C.) Anarquía (7 califas daeshitas) 1. Puzur-Sin (c. hacia 1740 a. C.) 2. Assur-dugul, usurpador 3. Ashur-apla-idi, usurpador 4. Nasir-Sin, usurpador 5. Sin-namir, usurpador 6. Ipqi-Ishtar, usurpador 7. Adad-salulu, usurpador Dinastía de Adasi (25 califas daeshitas) 1. Adasi (c. 1700 a. C.)1 2. Belu-bani (1700-1691 a. C.) 3. Libaia (1690-1674 a. C.) 4. Sharma-Adad I (1673-1662 a. C.) 5. Iptar-Sin (1661-1650 a. -

NABU 2020 2 Compilé 08 NZ

ISSN 0989-5671 2020 N° 2 (juin) NOTES BRÈVES 38) A Cylinder Seal with a Spread-Wing Eagle and Two Ruminants from Baylor University’s Mayborn Museum — This study shares the (re)discovery of a cylinder seal (AR 12517) housed at Baylor University’s Mayborn Museum Complex.1) The analysis of the seal offers two contributions: First, the study offers a rare record of the business transaction of a cylinder seal by the famous orientalist Edgar J. Banks. Second, the study adds an exceptional and well-preserved example of a cylinder seal engraved with the motif of a spread-wing eagle and two ruminants to the corpus of ancient Near Eastern seals. The study of this motif reveals that the seal published here offers one of the very few examples of a single-register seal which features a spread-wing eagle flanked by a standing caprid and stag. Acquisition History The museum purchased the cylinder seal for $8 from Edgar J. Banks on April 1st, 1937. Various records indicate that Banks traveled to Texas occasionally for speaking engagements and even sold cuneiform tablets to several institutions and individuals in Texas.2) While Banks sold tens of thousands of cuneiform tablets throughout the U.S., this study adds to the comparably modest number of cylinder seals sold by Banks.3) Although Banks’ original letter no longer remains, the acquisition record transcribes Banks’ words as follow: (Seal cylinders) were used for two distinct purposes. First, they were used to roll over the soft clay of the Babylonian contract tablets after they were inscribed, to legalize the contract and to make it impossible to forge or change the contract. -

Asszíria Állammá Alakulása Az Ie

Egy eltűnt birodalom nyomában Asszír birodalom tündöklése és bukása Közép-Kelet kisebb népeire, népelemeire gondolva láthatjuk, hogy mikor tudják létrehozni a maguk államát. Ez a folyamat abban az időben zajlik le, mikor a folyamköz nagy hatalmai, továbbá a termékenyfélhold területén, vagy a perifériáján elhelyezkedő hatalmak meggyengülnek, a politikai hatalmukat, akaratukat már nem tudják olyan intenzitással kifejteni, mint korábban. Tehát a belső problémák, illetve a külső hatások meggyengítették a hatalmukat. Nézzük meg melyek voltak ezek a hatások? I. A népek szétrajzásának a kora ez az időszak, amely az ie. XIV. század során már jól látható, megjelennek észak felől azok a népek, népelemek, amelyek olyan új hatást érnek el, melyek a folyamköz hatalmát érintik, ilyenek a hadifelszerelésben tapasztalható minőségi változások. II. A felvevő piacok lehetőségei, azok erőszakos megszerzése, továbbá a katonai jelenlétük a környező területeken. III. Egy új harcmodorral szinte minden véderőt meg tudtak semmisíteni és nem utolsó sorban a ló megjelenése a harci eszközök között. A ló megjelenése újat vitt a harcászat elemei közé. A hadművészet terén jelentős előnyt jelentett, mert a mozgásuk sebességét két, háromszorosára tudták növelni. Láthatjuk, e népek örökségéből, hogy a mozgás gyorsaságán túl olyan új fegyverek is megjelentek, melyek a hadviselés eszközeiként évezredekig megmaradtak. Ilyenek voltak a harciszekér, a harckocsi, amely megváltoztatta a harcmodort, hiszen a kocsin tartózkodó hajtónak nem kizárólagosan volt a feladata az ellenség leküzdése, mert az íjász ott volt mellette, akinek a feladata volt nyivánvalóan az ellenséges élőerő leküzdése. A harckocsi maga is harci eszköz volt, mert úgy volt kialakítva, hogy az élőerő ellenséges erőiben kárt tegyen, illetve egymaga is meg tudja semmisíteni az ellenség élő erejét. -

Witchcraft, Demonology and Magic

Witchcraft, Demonology and Magic • Marina Montesano Witchcraft, Demonology and Magic Edited by Marina Montesano Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Religions www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Witchcraft, Demonology and Magic Witchcraft, Demonology and Magic Special Issue Editor Marina Montesano MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade Special Issue Editor Marina Montesano Department of Ancient and Modern Civilizations, Universita` degli Studi di Messina Italy Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Religions (ISSN 2077-1444) from 2019 to 2020 (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/religions/special issues/witchcraft). For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03928-959-2 (Pbk) ISBN 978-3-03928-960-8 (PDF) c 2020 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Special Issue Editor ...................................... vii Marina Montesano Introduction to the Special Issue: Witchcraft, Demonology and Magic Reprinted from: Religions 2020, 11, 187, doi:10.3390/rel11040187 .................. -

Easy Latin Stories for Beginners

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com €ngîí0b ФсЬооиШ001С0 Edited by FRANCIS STORR, M.A., CHIEF MASTER OF MODERN SUBJECTS IN MERCHANT TAYLORS' SCHOOL Small Svo. THOMSON'S SEASONS : Winter. With an Introduction to the Series. By the Rev. J. F. Bright. u. COWPER'S TASK. By Francis Storr, M.A at. Part I. (Book I.— The Sofa; Book II.— The Timepiece) ad. Part II. (Book III.— The Garden ; Book IV.— The Winter Evening) ad. Part III. (Book V.— The Winter Morning Walk ; Book VI.— The Winter Walk at Noon) ad. SCOTT'S LAY OP THE LAST MINSTREL. By J. Surtees Phillpotts, M.A., Head-Master of Bedford Grammar School. 2i. 6d. ; or in Four Parts, ad. each. SCOTT'S LADY OP THE LAKE. By R. W. Taylor, M.A, Head-Master of Kelly College, Tavistock. гг. or in Three Parts, ad. each. NOTES TO SCOTT'S WAVERLEY. By H. W. Eve, M.A. it.; Waverley and Notes, ai. 6d. TWENTY OP BACON'S ESSAYS. By Francis Storr, M.A. u. SIMPLE POEMS. By W. E. Mullins, M.A, Assistant-Master at Marlborough College. 8*i. SELECTIONS PROM WORDSWORTH'S POEMS. By H. H. Türner, B.A., late Scholar of Trinity College, Cambridge. и WORDSWORTH'S EXCURSION: The Wanderer. By H. H. Turner, B.A. is. MILTON'S PARADISE LOST. By Francis Storr, M.A. Book I. ad. Book II. ad. MILTON'S L'ALLEGRO, IL PENSEROSO, AND LYCIDAS. -

ZECHARIAH. Ilonbon: C

~be <!Catnbrftrgc 35tblt for ~tboobs anl:I <!to llcgc~. HAGGAI AND ZECHARIAH. iLonbon: c. J. CLA y AND SONS, CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS WAREHOUSE, AVE MARIA LANE. QI'.ambribge: DEIGHTON, BELL, AND CO, 1.tip)ig: F. A. BROCKHAUS. ~f)t Qtambrtbgt 13tblt for §,cDoolu anb <ltolltgtfS. GENERAL EDITOR:-J. J. s. PEROWNE, D.D. DEAN OF PETERBOROUGH. HAGGAI AND ZECH AR I AH, WITH NOTES AND INTRODUCTION BY THE VEN. T. T. PEROWNE, 13.D. ARCHDEACON OF NORWICH; LATE FELLOW OF CORPUS CHRISTI COLLEGE, CAMllRIDGE. EDITED FOR THE SYNDICS OF THE UNIVERSITY PRESS. QC.ambtib'gt : AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS. 1890 [All Rights reserved.] Qtamhti'!Jgr: PRINTED BY C, J, CLAY, M.A. AND SONS, AT THE UNIVERSITY Pr.ESS, PREFACE BY THE GENERAL EDITOR. THE General Editor of The Cambri'dge Bible for Schools thinks it right to say that he does not hold himself responsible either for the interpretation of particular passages which the Editors of the several Books have adopted, or for any opinion on points of doctrine that they may have expressed. In the New Testament more especially questions arise of the deepest theological import, on which the ablest and most conscientious interpreters have differed and always will differ. His aim has been in all such cases to leave each Contributor to the unfettered exercise of his own judgment, only taking care that mere controversy should as far as possible be avoided. He has contented himself. chiefly with a careful revision of the notes, with pointing out omissions, with 6 PREFACE. suggesting occasionally a reconsideration of some question, or a fuller treatment of difficult passages, and the like.