Mesopotamian Chronology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cuneiform Digital Library Preprints <

Cuneiform Digital Library Preprints <http://cdli.ucla.edu/?q=cuneiform-digital-library-preprints> Hosted by the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (<http://cdli.ucla.edu>) Editor: Bertrand Lafont (CNRS, Nanterre) Number 6 Title: „Nachdem das Königtum vom Himmel herabgekommen war…“. Untersuchungen zur Sumerischen Königliste. Author: Jörg Kaula Posted to web: 21 November 2016 „NACHDEM DAS KÖNIGTUM VOM HIMMEL HERABGEKOMMEN WAR…“ Untersuchungen zur Sumerischen Königsliste Von Jörg Kaula 3 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Die Tonprismen der Weld-Blundell-Collection im Ashmolean Museum in Oxford 5 2 Königslisten in der Keilschriftliteratur 6 3 Die Sumerische Königsliste 7 3.1 Die „antediluvian section“ 11 3.2 Die Ur – Isin-Königsliste 12 3.3 Der Kern der Sumerischen Königsliste 12 4 Die SKL in der Forschung 14 5 Die Bedeutung der Zahlen 17 6 Das Umfeld und der Sinn der SKL 22 7 Das Königtum 23 8 Die Genesis der SKL von Naram-Sîn bis zu den Königen von Isin 24 9 Die Rekonstruktion des Weld-Blundell-Prismas 26 10 Die Sumerische Königliste – Transliteration 28 11 Deutsche Übersetzung 44 12 Kommentar zur Rekonstruktionsfassung 54 13 Literaturverzeichnis 69 4 Abstract The duration of the First Dynasty of Kish, 24510 years as provided by the Sumerian King List (SKL), is generally held as a purely mythical account without any historical reliability. However, a careful examination of the SKL’s most complete version in the Weld-Blundell Prism (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, inv. no.WB. 1923.444) not only allows us to reconstruct the text itself by completing lost parts by some other recently published versions of the SKL. Also we get some further insight into the metrological system used by the authors of the SKL. -

The Sweep of History

STUDENT’S World History & Geography 1 1 1 Essentials of World History to 1500 Ver. 3.1.10 – Rev. 2/1/2011 WHG1 The following pages describe significant people, places, events, and concepts in the story of humankind. This information forms the core of our study; it will be fleshed-out by classroom discussions, audio-visual mat erials, readings, writings, and other act ivit ies. This knowledge will help you understand how the world works and how humans behave. It will help you understand many of the books, news reports, films, articles, and events you will encounter throughout the rest of your life. The Student’s Friend World History & Geography 1 Essentials of world history to 1500 History What is history? History is the story of human experience. Why study history? History shows us how the world works and how humans behave. History helps us make judgments about current and future events. History affects our lives every day. History is a fascinating story of human treachery and achievement. Geography What is geography? Geography is the study of interaction between humans and the environment. Why study geography? Geography is a major factor affecting human development. Humans are a major factor affecting our natural environment. Geography affects our lives every day. Geography helps us better understand the peoples of the world. CONTENTS: Overview of history Page 1 Some basic concepts Page 2 Unit 1 - Origins of the Earth and Humans Page 3 Unit 2 - Civilization Arises in Mesopotamia & Egypt Page 5 Unit 3 - Civilization Spreads East to India & China Page 9 Unit 4 - Civilization Spreads West to Greece & Rome Page 13 Unit 5 - Early Middle Ages: 500 to 1000 AD Page 17 Unit 6 - Late Middle Ages: 1000 to 1500 AD Page 21 Copyright © 1998-2011 Michael G. -

Iranian Languages in the Persian Achamenid

ANALYZING INTER-VOLATILITY STRUCTURE TO DETERMINE OPTIMUM HEDGING RATIO FOR THE JET PJAEE, 18 (4) (2021) FUEL The Function of Non- Iranian Languages in the Persian Achamenid Empire Hassan Kohansal Vajargah Assistant professor of the University of Guilan-Rasht -Iran Email: hkohansal7 @ yahoo.com Hassan Kohansal Vajargah: The Function of Non- Iranian Languages in the Persian Achamenid Empire -- Palarch’s Journal Of Archaeology Of Egypt/Egyptology 18(4). ISSN 1567-214x Keywords: The Achamenid Empire, Non-Iranian languages, Aramaic language, Elamite language, Akkedi language, Egyptian language. ABSTRACT In the Achaemenid Empire( 331-559 B.C.)there were different tribes with various cultures. Each of these tribes spoke their own language(s). They mainly included Iranian and non- Iranian languages. The process of changes in the Persian language can be divided into three periods, namely , Ancient , Middle, and Modern Persian. The Iranian languages in ancient times ( from the beginning of of the Achaemenids to the end of the Empire) included :Median,Sekaee,Avestan,and Ancient Persian. At the time of the Achaemenids ,Ancient Persian was the language spoken in Pars state and the South Western part of Iran.Documents show that this language was not used in political and state affairs. The only remnants of this language are the slates and inscriptions of the Achaemenid Kings. These works are carved on stone, mud,silver and golden slates. They can also be found on coins,seals,rings,weights and plates.The written form of this language is exclusively found in inscriptions. In fact ,this language was used to record the great and glorious achivements of the Achaemenid kings. -

The Sumerian King List the Sumerian King List (SKL) Dates from Around 2100 BCE—Near the Time When Abram Was in Ur

BcResources Genesis The Sumerian King List The Sumerian King List (SKL) dates from around 2100 BCE—near the time when Abram was in Ur. Most ANE scholars (following Jacobsen) attribute the original form of the SKL to Utu-hejel, king of Uruk, and his desire to legiti- mize his reign after his defeat of the Gutians. Later versions included a reference or Long Chronology), 1646 (Middle to the Great Flood and prefaced the Chronology), or 1582 (Low or Short list of postdiluvian kings with a rela- Chronology). The following chart uses tively short list of what appear to be the Middle Chronology. extremely long-reigning antediluvian Text. The SKL text for the following kings. One explanation: transcription chart was originally in a narrative form or translation errors resulting from and consisted of a composite of several confusion of the Sumerian base-60 versions (see Black, J.A., Cunningham, and the Akkadian base-10 systems G., Fluckiger-Hawker, E, Robson, E., of numbering. Dividing each ante- and Zólyomi, G., The Electronic Text diluvian figure by 60 returns reigns Corpus of Sumerian Literature (http:// in harmony with Biblical norms (the www-etcsl.orient.ox.ac.uk/), Oxford bracketed figures in the antediluvian 1998-). The text was modified by the portion of the chart). elimination of manuscript references Final versions of the SKL extended and by the addition of alternative the list to include kings up to the reign name spellings, clarifying notes, and of Damiq-ilicu, king of Isin (c. 1816- historical dates (typically in paren- 1794 BCE). thesis or brackets). The narrative was Dates. -

{PDF} Ancient Civilizations the Near East and Mesoamerica 2Nd Edition

ANCIENT CIVILIZATIONS THE NEAR EAST AND MESOAMERICA 2ND EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK C C Lamberg-Karlovsky | 9780881338348 | | | | | Ancient Civilizations The near East and Mesoamerica 2nd edition PDF Book Thanks to their artwork, we have a very good idea of how they looked: men of short stature, but with muscular bodies, that shaved their faces and heads. Their known homeland was centred on Subartu , the Khabur River valley, and later they established themselves as rulers of small kingdoms throughout northern Mesopotamia and Syria. Add to Wishlist. They are the most striking constructions in their monumental funerary complex, the position of which symbolized the journey of the deceased ruler to the western realm of the dead. The River Nile was the center of Egyptian life. Rating details. Later dynasties promoted the worship of Ra, the solar god who ruled the world. Deanne rated it really liked it Feb 15, Scholars even have used the term 'Aramaization' for the Assyro-Babylonian peoples' languages and cultures, that have become Aramaic-speaking. Laurelyn Anne added it Oct 23, It has Nefertiti on the front, need I say more? Luwian was also the language spoken in the Neo-Hittite states of Syria , such as Melid and Carchemish , as well as in the central Anatolian kingdom of Tabal that flourished around BC. Priests were seers who predicted the future, acted as oracles, explained dreams, and offered sacrifices. The great Sumerian invention was cuneiform writing, which made it possible to share their thoughts and the events that affected them with future generations. A'annepada Meskiagnun Elulu Balulu. Rick rated it it was amazing Oct 19, Twenty-seventh Dynasty of Egypt Achaemenid conquest of Egypt. -

2210 Bc 2200 Bc 2190 Bc 2180 Bc 2170 Bc 2160 Bc 2150 Bc 2140 Bc 2130 Bc 2120 Bc 2110 Bc 2100 Bc 2090 Bc

2210 BC 2200 BC 2190 BC 2180 BC 2170 BC 2160 BC 2150 BC 2140 BC 2130 BC 2120 BC 2110 BC 2100 BC 2090 BC Fertile Crescent Igigi (2) Ur-Nammu Shulgi 2192-2190BC Dudu (20) Shar-kali-sharri Shu-Turul (14) 3rd Kingdom of 2112-2095BC (17) 2094-2047BC (47) 2189-2169BC 2217-2193BC (24) 2168-2154BC Ur 2112-2004BC Kingdom Of Akkad 2234-2154BC ( ) (2) Nanijum, Imi, Elulu Imta (3) 2117-2115BC 2190-2189BC (1) Ibranum (1) 2180-2177BC Inimabakesh (5) Ibate (3) Kurum (1) 2127-2124BC 2113-2112BC Inkishu (6) Shulme (6) 2153-2148BC Iarlagab (15) 2121-2120BC Puzur-Sin (7) Iarlaganda ( )(7) Kingdom Of Gutium 2177-2171BC 2165-2159BC 2142-2127BC 2110-2103BC 2103-2096BC (7) 2096-2089BC 2180-2089BC Nikillagah (6) Elulumesh (5) Igeshaush (6) 2171-2165BC 2159-2153BC 2148-2142BC Iarlagash (3) Irarum (2) Hablum (2) 2124-2121BC 2115-2113BC 2112-2110BC ( ) (3) Cainan 2610-2150BC (460 years) 2120-2117BC Shelah 2480-2047BC (403 years) Eber 2450-2020BC (430 years) Peleg 2416-2177BC (209 years) Reu 2386-2147BC (207 years) Serug 2354-2124BC (200 years) Nahor 2324-2176BC (199 years) Terah 2295-2090BC (205 years) Abraham 2165-1990BC (175) Genesis (Moses) 1)Neferkare, 2)Neferkare Neby, Neferkamin Anu (2) 3)Djedkare Shemay, 4)Neferkare 2169-2167BC 1)Meryhathor, 2)Neferkare, 3)Wahkare Achthoes III, 4)Marykare, 5)............. (All Dates Unknown) Khendu, 5)Meryenhor, 6)Neferkamin, Kakare Ibi (4) 7)Nykare, 8)Neferkare Tereru, 2167-2163 9)Neferkahor Neferkare (2) 10TH Dynasty (90) 2130-2040BC Merenre Antyemsaf II (All Dates Unknown) 2163-2161BC 1)Meryibre Achthoes I, 2)............., 3)Neferkare, 2184-2183BC (1) 4)Meryibre Achthoes II, 5)Setut, 6)............., Menkare Nitocris Neferkauhor (1) Wadjkare Pepysonbe 7)Mery-........, 8)Shed-........, 9)............., 2183-2181BC (2) 2161-2160BC Inyotef II (-1) 2173-2169BC (4) 10)............., 11)............., 12)User...... -

Toxicology in Antiquity

TOXICOLOGY IN ANTIQUITY Other published books in the History of Toxicology and Environmental Health series Wexler, History of Toxicology and Environmental Health: Toxicology in Antiquity, Volume I, May 2014, 978-0-12-800045-8 Wexler, History of Toxicology and Environmental Health: Toxicology in Antiquity, Volume II, September 2014, 978-0-12-801506-3 Wexler, Toxicology in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, March 2017, 978-0-12-809554-6 Bobst, History of Risk Assessment in Toxicology, October 2017, 978-0-12-809532-4 Balls, et al., The History of Alternative Test Methods in Toxicology, October 2018, 978-0-12-813697-3 TOXICOLOGY IN ANTIQUITY SECOND EDITION Edited by PHILIP WEXLER Retired, National Library of Medicine’s (NLM) Toxicology and Environmental Health Information Program, Bethesda, MD, USA Academic Press is an imprint of Elsevier 125 London Wall, London EC2Y 5AS, United Kingdom 525 B Street, Suite 1650, San Diego, CA 92101, United States 50 Hampshire Street, 5th Floor, Cambridge, MA 02139, United States The Boulevard, Langford Lane, Kidlington, Oxford OX5 1GB, United Kingdom Copyright r 2019 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, further information about the Publisher’s permissions policies and our arrangements with organizations such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions. This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein). -

The Calendars of Ebla. Part III. Conclusion

Andrews Unir~ersitySeminary Studies, Summer 1981, Vol. 19, No. 2, 115-126 Copyright 1981 by Andrews University Press. THE CALENDARS OF EBLA PART 111: CONCLUSION WILLIAM H. SHEA Andrews University In my two preceding studies of the Old and New Calendars of Ebla (see AUSS 18 [1980]: 127-137, and 19 [1981]: 59-69), interpreta- tions for the meanings of 22 out of 24 of their month names have been suggested. From these studies, it is evident that the month names of the two calendars can be analyzed quite readily from the standpoint of comparative Semitic linguistics. In other words, the calendars are truly Semitic, not Sumerian. Sumerian logograms were used for the names of two months of the Old Calendar and three months of the New Calendar, but it is most likely that the scribes at Ebla read these logograms with a Semitic equivalent. In the cases of the three logograms in the New Calendar these equiva- lents are reasonably clear, but the meanings of the names of the seventh and eighth months in the Old Calendar remain obscure. Not only do these month names lend themselves to a ready analysis on the basis of comparative Semitic linguistics, but, as we have also seen, almost all of them can be analyzed satisfactorily just by comparing them with the vocabulary of biblical Hebrew. Given some simple and well-known phonetic shifts, Hebrew cognates can be suggested for some 20 out of 24 of the month names in these two calendars. Some of the etymologies I have suggested may, of course, be wrong; but even so, the rather full spectrum of Hebrew cognates available for comparison probably would not be diminished greatly. -

Ancient Persian Civilization

Ancient Persian Civilization Dr. Anousha Sedighi Associate Professor of Persian [email protected] Summer Institute: Global Education through film Middle East Studies Center Portland State University Students hear about Iran through media and in the political context → conflict with U.S. How much do we know about Iran? (people, places, events, etc.) How much do we know about Iran’s history? Why is it important to know about Iran’s history? It helps us put today’s conflicts into context: o 1953 CIA coup (overthrow of the first democratically elected Prime Minister: Mossadegh) o Hostage crisis (1979-1981) Today we learn about: Zoroastrianism (early monotheistic religion, roots in Judaism, Christianity, Islam) Cyrus the great (founder of Persian empire, first declaration of human rights) Foreign invasions of Persia (Alexander, Arab invasion, etc.) Prominent historical figures (Ferdowsi, Avicenna, Rumi, Razi, Khayyam, Mossadegh, Artemisia, etc.) Sounds interesting! Do we have educations films about them? Yes, in fact most of them are available online! Zoroaster Zoroaster: religious leader Eastern Iran, exact birth/time not certain Varies between 6000-1000 BC Promotes peace, goodness, love for nature Creator: Ahura-Mazda Three principles: Good thoughts Good words Good deeds Influenced Judaism, Christianity, Islam Ancient Iranian Peoples nd Middle of 2 melluniuem (Nomadic people) Aryan → Indo European tribe → Indo-Iranian Migrated to Iranian Plateau (from Eurasian plains) (Persians, Medes, Scythians, Bactrians, Parthians, Sarmatians, -

“Going Native: Šamaš-Šuma-Ukīn, Assyrian King of Babylon” Iraq

IRAQ (2019) Page 1 of 22 Doi:10.1017/irq.2019.1 1 GOING NATIVE: ŠAMAŠ-ŠUMA-UKĪN, ASSYRIAN KING OF BABYLON By SHANA ZAIA1 Šamaš-šuma-ukīn is a unique case in the Neo-Assyrian Empire: he was a member of the Assyrian royal family who was installed as king of Babylonia but never of Assyria. Previous Assyrian rulers who had control over Babylonia were recognized as kings of both polities, but Šamaš-šuma-ukīn’s father, Esarhaddon, had decided to split the empire between two of his sons, giving Ashurbanipal kingship over Assyria and Šamaš-šuma-ukīn the throne of Babylonia. As a result, Šamaš-šuma-ukīn is an intriguing case-study for how political, familial, and cultural identities were constructed in texts and interacted with each other as part of royal self- presentation. This paper shows that, despite Šamaš-šuma-ukīn’s familial and cultural identity as an Assyrian, he presents himself as a quintessentially Babylonian king to a greater extent than any of his predecessors. To do so successfully, Šamaš-šuma-ukīn uses Babylonian motifs and titles while ignoring the Assyrian tropes his brother Ashurbanipal retains even in his Babylonian royal inscriptions. Introduction Assyrian kings were recognized as rulers in Babylonia starting in the reign of Tiglath-pileser III (744– 727 BCE), who was named as such in several Babylonian sources including a king list, a chronicle, and in the Ptolemaic Canon.2 Assyrian control of the region was occasionally lost, such as from the beginning until the later years of Sargon II’s reign (721–705 BCE) and briefly towards the beginning of Sennacherib’s reign (704–681 BCE), but otherwise an Assyrian king occupying the Babylonian throne as well as the Assyrian one was no novelty by the time of Esarhaddon’s kingship (680–669 BCE). -

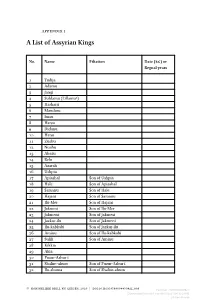

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM Via Free Access 198 Appendix I

Appendix I A List of Assyrian Kings No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 1 Tudija 2 Adamu 3 Jangi 4 Suhlamu (Lillamua) 5 Harharu 6 Mandaru 7 Imsu 8 Harsu 9 Didanu 10 Hanu 11 Zuabu 12 Nuabu 13 Abazu 14 Belu 15 Azarah 16 Ushpia 17 Apiashal Son of Ushpia 18 Hale Son of Apiashal 19 Samanu Son of Hale 20 Hajani Son of Samanu 21 Ilu-Mer Son of Hajani 22 Jakmesi Son of Ilu-Mer 23 Jakmeni Son of Jakmesi 24 Jazkur-ilu Son of Jakmeni 25 Ilu-kabkabi Son of Jazkur-ilu 26 Aminu Son of Ilu-kabkabi 27 Sulili Son of Aminu 28 Kikkia 29 Akia 30 Puzur-Ashur I 31 Shalim-ahum Son of Puzur-Ashur I 32 Ilu-shuma Son of Shalim-ahum © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/9789004430921_008 Fei Chen - 9789004430921 Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM via free access 198 Appendix I No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 33 Erishum I Son of Ilu-shuma 1974–1935 34 Ikunum Son of Erishum I 1934–1921 35 Sargon I Son of Ikunum 1920–1881 36 Puzur-Ashur II Son of Sargon I 1880–1873 37 Naram-Sin Son of Puzur-Ashur II 1872–1829/19 38 Erishum II Son of Naram-Sin 1828/18–1809b 39 Shamshi-Adad I Son of Ilu-kabkabic 1808–1776 40 Ishme-Dagan I Son of Shamshi-Adad I 40 yearsd 41 Ashur-dugul Son of Nobody 6 years 42 Ashur-apla-idi Son of Nobody 43 Nasir-Sin Son of Nobody No more than 44 Sin-namir Son of Nobody 1 year?e 45 Ibqi-Ishtar Son of Nobody 46 Adad-salulu Son of Nobody 47 Adasi Son of Nobody 48 Bel-bani Son of Adasi 10 years 49 Libaja Son of Bel-bani 17 years 50 Sharma-Adad I Son of Libaja 12 years 51 Iptar-Sin Son of Sharma-Adad I 12 years -

Religion and Reconciliation in Greek Cities (2010)

Religion and Reconciliation in Greek Cities AMERICAN PHILOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION american classical studies volume 54 Series Editor Kathryn J. Gutzwiller Studies in Classical History and Society Meyer Reinhold Sextus Empiricus The Transmission and Recovery of Pyrrhonism Luciano Floridi The Augustan Succession An Historical Commentary on Cassius Dio’s Roman History Books 55 56 (9 B.C. A.D. 14) Peter Michael Swan Greek Mythography in the Roman World Alan Cameron Virgil Recomposed The Mythological and Secular Centos in Antiquity Scott McGill Representing Agrippina Constructions of Female Power in the Early Roman Empire Judith Ginsburg Figuring Genre in Roman Satire Catherine Keane Homer’s Cosmic Fabrication Choice and Design in the Iliad Bruce Heiden Hyperides Funeral Oration Judson Herrman Religion and Reconciliation in Greek Cities The Sacred Laws of Selinus and Cyrene Noel Robertson Religion and Reconciliation in Greek Cities The Sacred Laws of Selinus and Cyrene NOEL ROBERTSON 1 2010 3 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright q 2010 by the American Philological Association Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.