The Wright Brothers' Legacy and Dayton, Ohio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autumn 2018, Vol

www.telcomhistory.org (303) 296‐1221 Autumn 2018, Vol. 23, no.3 Jody Georgeson, editor A Message from Our Director As I write this, Summer is coming to a close and you can feel the change of the seasons in the air. Kids are going Back to school, nights are getting cooler, leaves are starting to turn and soon our days will Be filled with holiday celeBrations. We have a lot to Be thankful for. We had a great celeBration in July at our Seattle Connections Museum. Visitors joined us from near and far for our Open House. We are grateful to all the volunteers and Seattle Board memBers for their hard work and dedication in making this a successful event. Be sure to read more about the new exhiBit that was dedicated in honor of our late Seattle curator, Don Ostrand, in this issue. I would also like to thank our partners at Telephone Collectors International (TCI) and JKL Museum who traveled from California to help us celeBrate. As always, we welcome anyone who wants to visit either of our locations or to volunteer to help preserve the history of the telecommunications industry. Visit our website at www.telcomhistory.org for more information. Enjoy the remainder of 2018. Warm regards, Lisa Berquist Executive Director Ostrand Collection Ribbon-cutting at Connections Museum Seattle! By Dave Dintenfass A special riBBon-cutting celeBration took place on 14 July 2018 at Connections Museum Seattle. This marked the opening of a special room to display the Ostrand Collection. This collection, on loan from the family of our late curator Don Ostrand, contains unusual items not featured elsewhere in our museum. -

90 Years of Flight Test in the Miami Valley

in the MiamiValley History Offke Aeronautical Systems Center Air Force Materiel Command ii FOREWORD Less than one hundred years ago, Lord Kelvin, the most prominent scientist of his generation, remarked that he had not “the smallest molecule of faith’ in any form of flight other than ballooning. Within a decade of his damningly pessimistic statement, the Wright brothers were routinely puttering through the skies above Huffman Prairie, pirouetting about in their frail pusher biplanes. They were there because, unlike Kelvin, they saw opportunity, not difficulty, challenge, not impossibility. And they had met that challenge, seized that opportunity, by taking the work of their minds, transforming it by their hands, making a series of gliders and, then, finally, an actual airplane that they flew. Flight testing was the key to their success. The history of flight testing encompassesthe essential history of aviation itself. For as long as humanity has aspired to fly, men and women of courage have moved resolutely from intriguing concept to practical reality by testing the result of their work in actual flight. In the eighteenth and nineteenth century, notable pioneers such asthe French Montgolfier brothers, the German Otto Lilienthal, and the American Octave Chanute blended careful study and theoretical speculation with the actual design, construction, and testing of flying vehicles. Flight testing reallycame ofage with the Wright bro!hers whocarefullycombined a thorough understanding of the problem and potentiality of flight with-for their time-sophisticated ground and flight-test methodolo- gies and equipment. After their success above the dunes at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina on December 17,1903, the brothers determined to refine their work and generate practical aircraft capable of routine operation. -

Dayton,OH Sightseeing National Museum of the U.S. Air Force

Dayton,OH Sightseeing National Museum of the U.S. Air Force A “MUST SEE!” in Dayton, the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force is the world’s largest and oldest military aviation museum and Ohio’s most visited FREE tourist attraction with nearly 1.3 million annual visitors. This world-renowned museum features more than 360 aerospace vehicles and missiles and thousands of artifacts amid more than 17 acres of indoor exhibit space. Exhibits are arranged chronologically so it’s easy to visit the areas that interest you most. Examine a Wright Brothers plane, sit in a jet cockpit, walk through a NASA shuttle crew compartment trainer, or stand in awe of the world’s only permanent public display of a B-2 stealth bomber. Feeling adventurous? Check out the Morphis Movie Simulator Ride, a computer controlled simulator for the entire family. Capable of accommodating 12 passengers, the capsule rotates and gyrates on hydraulic lifts, giving the passengers the sensation of actually flying along. Dramamine may be required. Or, take in one of the multiple daily movies at the Air Force Museum Theatre’s new state-of-the-art D3D Cinema showing a wide range of films on a massive 80 foot by 60 foot screen. Satisfy your hunger at the Museum’s cafeteria (where you can even try out freeze-dried ‘astronaut ice cream!’), or shop for one-of-a-kind aviation gifts in the Museum’s impressive gift shop. And, just when you didn’t think it couldn’t happen, the best is getting even better! In 2016 a new fourth hangar will open. -

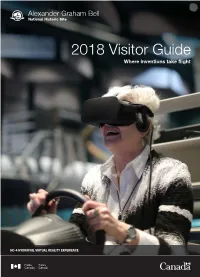

2018 Visitor Guide Where Inventions Take flight

2018 Visitor Guide Where inventions take flight HD-4 HYDROFOIL VIRTUAL REALITY EXPERIENCE How to reach us Alexander Graham Bell National Historic Site 559 Chebucto St (Route 205) Baddeck, Nova Scotia Canada 902-295-2069 [email protected] parkscanada.gc.ca/bell Follow us Welcome to Alexander Graham Bell /AGBNHS National Historic Site @ParksCanada_NS Imagine when travel and global communications as we know them were just a dream. How did we move from that reality to @parks.canada one where communication is instantaneous and globetrotting is an everyday event? Alexander Graham Bell was a communication and transportation pioneer, as well as a teacher, family man and humanitarian. /ParksCanadaAgency Alexander Graham Bell National Historic Site is an architecturally unique exhibit complex where models, replicas, photo displays, artifacts and films describe the fascinating life and work of Alexander Hours of operation Graham Bell. Programs such as our White Glove Tours complement May 18 – October 30, 2018 the exhibits at the site, which is situated on ten hectares of land 9 a.m. – 5 p.m. overlooking Baddeck Bay and Beinn Bhreagh peninsula, the location of the Bells’ summer home. Entrance fees In the words of Bell, a born inventor Adult: $7.80 “Wealth and fame are coveted by all men, but the hope of wealth or the desire for fame will never make an inventor…you may take away all that he has, Senior: $6.55 and he will go on inventing. He can no more help inventing than he can help Youth: free thinking or breathing. Inventors are born — not made.” — Alexander Graham Bell Starting January 1, 2018, admission to all Parks Canada places for youth 17 and under is free! There’s no better time to create lasting memories with the whole family. -

And Octavia Butler's Kindred Across the Sensory Line Emily Anne Bonner University of Tennessee, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Tennessee, Knoxville: Trace University of Tennessee, Knoxville Trace: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2018 Subversive Speculations: Reading Ann Petry's The Street and Octavia Butler's Kindred across the Sensory Line Emily Anne Bonner University of Tennessee, [email protected] Recommended Citation Bonner, Emily Anne, "Subversive Speculations: Reading Ann Petry's The Street and Octavia Butler's Kindred across the Sensory Line. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2018. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/5048 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Trace: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of Trace: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Emily Anne Bonner entitled "Subversive Speculations: Reading Ann Petry's The Street and Octavia Butler's Kindred across the Sensory Line." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. Michelle D. Commander, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Thomas F. Haddox, Mary E. Papke Accepted for the -

ARE DRONES a FORCE for GOOD? How Drones Are Being Used to Benefit Society

BRIEF FOOD AND DRINK CULTURE GEAR SPORTS STYLE WOMEN HOME > BANNER- HOME > MAGAZINE ARE DRONES A FORCE FOR GOOD? How drones are being used to benefit society By Matthew Priest Words: Max Mueller NEWSLETTER SUBSCRIPTION Get the lowdown on the week ahead to your inbox, together with reviews, exclusive competitions and the occasional funny list. Enter Your Email SUBSCRIBE MOST POPULAR THIS WEEK Read Shared Galleries HOW TO BULK UP LIKE A RUGBY PLAYER Drones usually feature in the news due to their controversial use as weapons of war or, more prosaically, for their use as fun but largely impractical toys. But what if the technology could be used to help the environment or save lives? This month, the UAE is again promoting the humanitarian use of drones with a $1 million competition that features the best designs from around the world. Here is a bird’s eye view of the technology and its pitfalls, in the Middle East and beyond. *** WHAT I’VE LEARNT: FLAVIO BRIATORE Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power station, April 10, 2015. Four years after the March 2011 meltdown, a stream of images is being recorded inside reactor No 1, one of three that was badly damaged after the plant was hit by a devastating tsunami. As the remote-controlled robot crawls through debris, the on-board searchlight struggles to penetrate a thick dust cloud. It also has to navigate charred concrete girders coated in solidified molten metal that now resemble warped stalactites. CESARO: 8 THINGS WE’VE At the bottom of the video screen is a digital display of the radiation exposure. -

Planning of Nuclear Power Systems

ASKO VUORINEN Planning of Nuclear Power Systems To Save the Planet Ekoenergo Oy August, 2011 The nuclear power could generate 27 % of electricity by 2050 and 34 % by 2075. Nuclear electricity generation can make the biggest change in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and it would be possible to limit the global temperature increase to 2 degrees Celsius by the year 2100. 1 Copyright © 2011 Ekoenergo Oy Lokirinne 8 A 25, 02320 Espoo, Finland Telephone (+358) 440451022 The book is available for internet orders www.optimalpowersystems.com Email (for orders and customer service enquires): [email protected] All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, scanning or otherwise, except under terms of copyright, without the permission in writing of the Publisher. Requests to the publisher should be addressed to Ekoenergo Oy, Lokirinne 8 A 25, 02320 Espoo, Finland or emailed to [email protected]. Comments to the author can be sent directly to [email protected]. Cover page: the Planet and Atoms. Created by my son Architect Teo-Tuomas Vuorinen 2 Table of Contents PREFACE ....................................................................................................................................................................... 13 .ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................................................................. -

Download This PDF File

OHIO JOURNAL OF SCIENCE BOOK REVIEWS 67 Younger brother Howard Jones, who also became a between the natural environment and the rich history medical doctor, enjoyed roaming the woods and fields of this special place. and supplied most of the nests and eggs that went into Huffman Prairie today is a 114-acre fragment the family “cabinet” and became the reference library for of its original area within the Wright-Patterson Air the drawings. Genevieve’s mother, Virginia, supported Force Base, a short distance east of Dayton, Ohio. In any project her daughter was involved with but had no 1986 the natural portion of the Huffman Prairie was personal interest in ornithology and natural history. designated as an Ohio Natural Landmark Area and in She also had no training as an artist. After Genevieve’s 1990, Huffman Prairie Flying Field was designated as death, Virginia’s love for her daughter and wishes to a National Historic Landmark. It is a component of honor her memory inspired her to join her husband the National Aviation Heritage Area. and son in the project. Virginia taught herself the The book weaves together several themes: an skills needed to draw on the lithographic stones and excellent history of the land even before the Wright how to color them. Genevieve’s friend, Eliza Shulze, brothers got involved, the brothers' work on drew additional plates and helped Virginia finish the developing and improving airplane design, and the coloring of plates. In all, Genevieve drew only five eventual development of Wright-Patterson Air Force plates, Eliza did ten plates, Howard drew eleven plates Base (which encompasses the Huffman Prairie). -

Catalogue of Paintings, Sculptures and Other Objects Exhibited During The

ART ' INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO CATALOGUE • OF PAINTINGS, ScuLPTURES AND OTHER OBJECTS EXHIBITED DURING THE WoRLD'S CoNGREssEs MAY 15 TO OCT. 31, 1893. THE ART INSTITUTE, Lake Front, opposite Adams Street, Chicago. THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO. CATALOGUE -OF- PAINTINGS, SCULPTURES AND OTHER OBJECTS EXHIBITED DURING THE WORLD'S CON- GRESSES. · SEPTEMBER, I893. CHICAGO, LAKE FRONT, HEAD OF ADAMS STREET. TRUSTEES OF THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO, !892-J. CHARLES L. HUTCHINSON, SAMUEL M. NICKERSON, DAVID W. IRWIN, MARTIN A. RYERSON, EDWARD E. A YER, WILLIAM . T. BAKER, ELIPHALET W. BLATCHFORD, NATHANIEL K. FAIRBANK, JAMES H. DOLE, ALBERT A. SPRAGUE, JOHN C. BLACK, ADOI;PHUS C. BARTLETT, . JOHN J. GLESSNER, CHARLES D. HAMILL, EDSON KEITH, TURLINGTON W. HARVEY. ALLISON V. ARM01J.R, HOMER N. HIBBARD, MARSHALL FIELD, GEORGE N . CULVER, PHILANDER C. HANFORD. OFFICERS CHARLES L. HUTCHINSON, JAMES H. DOLE, President. V{ce-President. LYMAN J . GAGE, N.H. CARPENTER, Treasurer. Secretary. W . M. R. FRENCH, ALFRED EMERSON, Director. Curator of Classical Antiquities. EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE <;HARLES L. HUTCHINSON, CHARLES D. HAMILL, JA)iES H. DOLE, JOHN C. BLACK, ALBERT A. SPRAGUE, MARTIN A. RYERSON, WILLIAM T . BAKER. THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO was incorporated May 24, 1879, for the purpose of maintaining a Museum and School of Art. The present building is built by the Art Institute and the World's Columbian Exposition jointly, at a cost of ~625,000, upon land granted by the city. At the end of the Fair the building will become the permanent and exclusive possession of· the Art Institute . During the Fair it is occupied by the World's Congresses. -

The Power for Flight: NASA's Contributions To

The Power Power The forFlight NASA’s Contributions to Aircraft Propulsion for for Flight Jeremy R. Kinney ThePower for NASA’s Contributions to Aircraft Propulsion Flight Jeremy R. Kinney Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Kinney, Jeremy R., author. Title: The power for flight : NASA’s contributions to aircraft propulsion / Jeremy R. Kinney. Description: Washington, DC : National Aeronautics and Space Administration, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017027182 (print) | LCCN 2017028761 (ebook) | ISBN 9781626830387 (Epub) | ISBN 9781626830370 (hardcover) ) | ISBN 9781626830394 (softcover) Subjects: LCSH: United States. National Aeronautics and Space Administration– Research–History. | Airplanes–Jet propulsion–Research–United States– History. | Airplanes–Motors–Research–United States–History. Classification: LCC TL521.312 (ebook) | LCC TL521.312 .K47 2017 (print) | DDC 629.134/35072073–dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017027182 Copyright © 2017 by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. The opinions expressed in this volume are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official positions of the United States Government or of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. This publication is available as a free download at http://www.nasa.gov/ebooks National Aeronautics and Space Administration Washington, DC Table of Contents Dedication v Acknowledgments vi Foreword vii Chapter 1: The NACA and Aircraft Propulsion, 1915–1958.................................1 Chapter 2: NASA Gets to Work, 1958–1975 ..................................................... 49 Chapter 3: The Shift Toward Commercial Aviation, 1966–1975 ...................... 73 Chapter 4: The Quest for Propulsive Efficiency, 1976–1989 ......................... 103 Chapter 5: Propulsion Control Enters the Computer Era, 1976–1998 ........... 139 Chapter 6: Transiting to a New Century, 1990–2008 .................................... -

Official News Letter AMA Chapter #3798

Chino Valley Model Aviators Official News Letter AMA Chapter #3798 April 25, 2017 Volume 20 Issue 4 www. chinovalleymodelaviators.org “To create an interest in, further the image of, and promote the hobby/sport of Bob Shanks’ German Trainer Arado 76 radio controlled aircraft” Inside this issue Presidents Message 2 Name This Plane 2 A-10 in a Tucson Sunset 2 Safety Column 3 Club Flying Photos 4 , 5 Eagles Hunting Drones 6 Gustave-whitehead Story 7 Name the Plane Answer 8 April General Meeting 9 This semi-scale plane was built from Model Airplane News plans over 10 years ago. Designed for glow, Bob converted it to electric and with the help of Randy Meathrell Life Survey finally test flew it for the first time ever. It needs a bigger electric motor for our altitude. Dale Tomlinson and His Little WACO Support Our Local Hobby Shop The Safeway Center Prescott Valley, AZ MAX & CINNIMON BANDY THEY SUPPORT OUR CLUB Please support them as well. CVMA OFFICIAL NEW SLETTER Page 2 Mike’s Blue Baby Field Chatter from CVMA President Michael Kidd: No Kidding! Greetings Fellow Pilots, can’t for whatever reason we Seems we still have a flight instructor for the last Well the annual spring can now have them join as problem with folks leaving three years, we now need winds are upon us but if you associate members. This the gate open. We have someone else to step up and get out early flying has been won’t affect many but will invested a lot of effort into fill that job. -

The Wright Brothers Played with As Small Boys

1878 1892 The Flying Toy: A small toy “helicopter”— made of wood with two twisted rubber bands to turn a small propeller—that the Wright brothers played with as small boys. The Bicycle Business: The Wright brothers opened a bicycle store in 1892. Their 1900 experience with bicycles aided them in their The Wright Way: investigations of flight. The Process of Invention The Search for Control: From their observations of how buzzards kept their balance, the Wright brothers began their aeronautical research in 1899 with a kite/glider. In 1900, they built their first glider designed to carry a pilot. Wilbur and Orville Wright Inventors Wilbur and Orville Wright placed their names firmly in the hall of great 1901 American inventors with the creation of the world’s first successful powered, heavier-than-air machine to achieve controlled, sustained flight Ohio with a pilot aboard. The age of powered flight began with the Wright 1903 Flyer on December 17, 1903, at Kill Devil Hills, NC. The Wright brothers began serious experimentation in aeronautics in 1899 and perfected a controllable craft by 1905. In six years, the Wrights had used remarkable creativity and originality to provide technical solutions, practical mechanical Birthplace design tools, and essential components that resulted in a profitable aircraft. They did much more than simply get a flying machine off the ground. They established the fundamental principles of aircraft design and engineering in place today. In 1908 and 1909, they demonstrated their flying machine pub- licly in the United States and Europe. By 1910, the Wright Company was of Aviation manufacturing airplanes for sale.