The Politics of Rammstein's Sound: Decoding a Production Aesthetic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rns Over the Long Term and Critical to Enabling This Is Continued Investment in Our Technology and People, a Capital Allocation Priority

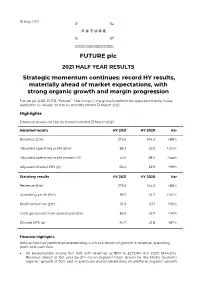

19 May 2021 FUTURE plc 2021 HALF YEAR RESULTS Strategic momentum continues: record HY results, materially ahead of market expectations, with strong organic growth and margin progression Future plc (LSE: FUTR, “Future”, “the Group”), the global platform for specialist media, today publishes its results for the six months ended 31 March 2021. Highlights Financial results for the six months ended 31 March 2021 Adjusted results HY 2021 HY 2020 Var Revenue (£m) 272.6 144.3 +89% Adjusted operating profit (£m)1 89.2 39.9 +124% Adjusted operating profit margin (%) 33% 28% +5ppt Adjusted diluted EPS (p) 65.4 32.9 +99% Statutory results HY 2021 HY 2020 Var Revenue (£m) 272.6 144.3 +89% Operating profit (£m) 59.7 24.7 +142% Profit before tax (£m) 56.9 27.1 +110% Cash generated from operations (£m) 85.9 35.7 +141% Diluted EPS (p) 40.7 21.8 +87% Financial highlights Robust first-half performance extending our track record of growth in revenue, operating profit and cash flow: An exceptionally strong first half, with revenue up 89% to £272.6m (HY 2020: £144.3m). Revenue ahead of last year by 21% on an organic2 basis, driven by the Media division’s organic2 growth of 30% and in particular digital advertising on-platform organic2 growth of 30% and eCommerce affiliates’ organic2 growth of 56%. US achieved revenue growth of 31% on an organic2 basis and UK revenues grew by 5% organically (UK has a higher mix of events and magazines revenues which were impacted more materially by the pandemic). -

Music 1000 Songs, 2.8 Days, 5.90 GB

Music 1000 songs, 2.8 days, 5.90 GB Name Time Album Artist Drift And Die 4:25 Alternative Times Vol 25 Puddle Of Mudd Weapon Of Choice 2:49 Alternative Times Vol 82 Black Rebel Motorcycle Club You'll Be Under My Wheels 3:52 Always Outnumbered, Never Outg… The Prodigy 08. Green Day - Boulevard Of Bro… 4:20 American Idiot Green Day Courage 3:30 ANThology Alien Ant Farm Movies 3:15 ANThology Alien Ant Farm Flesh And Bone 4:28 ANThology Alien Ant Farm Whisper 3:25 ANThology Alien Ant Farm Summer 4:15 ANThology Alien Ant Farm Sticks And Stones 3:16 ANThology Alien Ant Farm Attitude 4:54 ANThology Alien Ant Farm Stranded 3:57 ANThology Alien Ant Farm Wish 3:21 ANThology Alien Ant Farm Calico 4:10 ANThology Alien Ant Farm Death Day 4:33 ANThology Alien Ant Farm Smooth Criminal 3:29 ANThology Alien Ant Farm Universe 9:07 ANThology Alien Ant Farm The Weapon They Fear 4:38 Antigone Heaven Shall Burn To Harvest The Storm 4:45 Antigone Heaven Shall Burn Tree Of Freedom 4:49 Antigone Heaven Shall Burn Voice Of The Voiceless 4:53 Antigone (Slipcase - Edition) Heaven Shall Burn Rain 4:11 Ascendancy Trivium laid to rest 3:49 ashes of the wake lamb of god Now You've Got Something to Die … 3:39 Ashes Of The Wake Lamb Of God Relax Your Mind 4:07 Bad Boys 2 Soundtrack Loon Intro 0:12 Bad Boys 2 Soundtrack Bad Boys 2 Soundtrack Show Me Your Soul 5:20 Bad Boys 2 Soundtrack Loon Feat. -

How to Get Away with Copyright Infringement: Music Sampling As Fair Use

THIS VERSION MAY CONTAIN INACCURATE OR INCOMPLETE PAGE NUMBERS. PLEASE CONSULT THE PRINT OR ONLINE DATABASE VERSIONS FOR THE PROPER CITATION INFORMATION. NOTE HOW TO GET AWAY WITH COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT: MUSIC SAMPLING AS FAIR USE SAM CLAFLIN1 CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 102 II. BACKGROUND ............................................................................................ 104 A. History ............................................................................................ 104 i. Foundations of Copyright Law with Respect to Music ............ 104 ii. Music Sampling and Copyright ............................................... 105 B. The Fair Use Doctrine .................................................................... 107 i. Fair Use and Appropriation Art ................................................ 110 III. A CONTEMPORARY PERSPECTIVE ON MUSIC SAMPLING AND FAIR USE: ESTATE OF SMITH V. CASH MONEY RECORDS, INC. ................................ 113 A. Background ..................................................................................... 113 B. Analysis – An In-Depth Look at the Court’s Fair Use Approach in Estate of Smith ........................................................ 114 i. Factor One .............................................................................. 115 ii. Factor Two ............................................................................. 118 iii. Factor Three .......................................................................... -

Rammstein - Rosenrot Nur Ein Jahr Nach Dem Release Von „Reise,Reise“ Haben Rammstein Den Nächsten Longplayer Auf Den Markt Geworfen

Rammstein - Rosenrot Nur ein Jahr nach dem Release von „Reise,Reise“ haben Rammstein den nächsten Longplayer auf den Markt geworfen. Und wer jetzt denkt, na, da haben wir gewiß nur einen Schnellschuß zum schnellen Kohle machen veröffentlicht,wird sich nach dem Hören dieser CD eines besseren belehren lassen müssen. Rammstein - Rosenrot 1.Benzin 2.Mann gegen Mann 3.Rosenrot 4.Spring 5.Wo bist du 6.Stirb nicht vor mir // Dont Die Before I Do Feat. Sharleen Spiteri 7.Zerstören 8.Hilf mir 9.Te Quiero Puta! 10.Feuer und Wasser 11.Ein Lied Universal (Universal) Till Lindemann – Gesang Paul Landers – Gitarre Richard Kruspe Bernstein – Gitarre Christoph Schneider – Schlagzeug Oliver Riedel – Bass Christian "Flake" Lorenz – Keyboard Nur ein Jahr nach dem Release von „Reise,Reise“ haben Rammstein den nächsten Longplayer auf den Markt geworfen. Und wer jetzt denkt, na, da haben wir gewiß nur einen Schnellschuß zum schnellen Kohle machen veröffentlicht,wird sich nach dem Hören dieser CD eines besseren belehren lassen müssen. Denn textlich so gut wie hier, haben sich „Rammstein“ seit „Sehnsucht“ nicht mehr geäußert. Das beginnt mit „Spring“, einem der grandiosesten Texte, den die Band jemals geschrieben hat und wird nur noch von „Mann gegen Mann“ übertroffen, einem Text über Homosexualität, die durchaus die Chance hat, in den Schwulendiscos dieses Landes zur neuen Hymne zu avancieren. Der Text ist sehr tiefsinnig und wirkt in keinster Weise diskriminierend. Ich glaube, es hat sich in keiner Form jemals ein heterosexueller mann künstlerisch so poitiv über dieses Thema geäußert. Respekt. 1/2 Doch auch Knaller wie „Zestören“, ein Song über Gewalt gegen Gegenstände „Stirb nicht vor mir“, ein wunderschönes Liebeslied, oder „Rosenrot“ wissen mehr als nur zu gefallen. -

As of 02 June 2017 (Updated Regularly) ABOUT MIDEM

HIGHLIGHTS MIDEM 2017 as of 02 June 2017 (updated regularly) ABOUT MIDEM Midem is an annual international b2b event dedicated to the ALEXANDRE DENIOT new music ecosystem, with a tradeshow, conferences, Director of Midem competitions, networking events and live performances. It’s the place where music makers, cutting-edge technologies, brands & talents come together to enrich the passionate relationship Alexandre Deniot has been named between people & music, transform audience engagement and Director of Midem in January 2017. form new business connections. He brings with him over 15 years of experience within the music sector, mainly at Universal Music Group where he was most recently Business Development Director for UMG’s Paris-based digital division. In this capacity over the past two years, he spearheaded the development of Universal Music’s digital services in emerging markets and more specifically in Africa. Alexandre Deniot started his career in the music business in 2001 as part of Sony Music Entertainment’s sales The international music ecosystem comes to Midem: marketing team in Lyon, France. He joined Universal Music Group in 2002 as Regional Sales Manager for eastern France then southern France before being promoted to Key Account Manager (Physical Sales) in 2006 and Key Account Manager (Digital Sales) in 2009. Five years later he was named Head of Business Development at Universal Music Group’s digital division, managing Universal Music On Line, a specialist digital subsidiary of Universal Music. In January 2016 he took on the Business Development Director within the digital division in Paris. 2 MIDEM STORY WHERE BUSINESS HAPPENS WHERE TALENT SHINES WHERE IDEAS GROW As the essential relationship broker of the Discover new talent thanks to leading Get inspired by industry leaders from around international music ecosystem, Midem helps industry competitions: the world who share their in sight on today you grow your business. -

Of ABBA 1 ABBA 1

Music the best of ABBA 1 ABBA 1. Waterloo (2:45) 7. Knowing Me, Knowing You (4:04) 2. S.O.S. (3:24) 8. The Name Of The Game (4:01) 3. I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do (3:17) 9. Take A Chance On Me (4:06) 4. Mamma Mia (3:34) 10. Chiquitita (5:29) 5. Fernando (4:15) 11. The Winner Takes It All (4:54) 6. Dancing Queen (3:53) Ad Vielle Que Pourra 2 Ad Vielle Que Pourra 1. Schottische du Stoc… (4:22) 7. Suite de Gavottes E… (4:38) 13. La Malfaissante (4:29) 2. Malloz ar Barz Koz … (3:12) 8. Bourrée Dans le Jar… (5:38) 3. Chupad Melen / Ha… (3:16) 9. Polkas Ratées (3:14) 4. L'Agacante / Valse … (5:03) 10. Valse des Coquelic… (1:44) 5. La Pucelle d'Ussel (2:42) 11. Fillettes des Campa… (2:37) 6. Les Filles de France (5:58) 12. An Dro Pitaouer / A… (5:22) Saint Hubert 3 The Agnostic Mountain Gospel Choir 1. Saint Hubert (2:39) 7. They Can Make It Rain Bombs (4:36) 2. Cool Drink Of Water (4:59) 8. Heart’s Not In It (4:09) 3. Motherless Child (2:56) 9. One Sin (2:25) 4. Don’t We All (3:54) 10. Fourteen Faces (2:45) 5. Stop And Listen (3:28) 11. Rolling Home (3:13) 6. Neighbourhood Butcher (3:22) Onze Danses Pour Combattre La Migraine. 4 Aksak Maboul 1. Mecredi Matin (0:22) 7. -

Diplomarbeit

Diplomarbeit Titel der Diplomarbeit „Entstehung und Entwicklung von HipHop in Österreich“ - Etablierung der HipHop-Kultur in Österreich am Beispiel der vier wichtigsten Pioniere der dazugehörigen Musikrichtung Verfasser Frederik Dörfler angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2011 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 316 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Musikwissenschaft Betreuerin / Betreuer: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Michele Calella i Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Anmerkungen ................................................................................................................................. iv 2 Einleitung ........................................................................................................................................ iv 2.1 Vorhaben und Zielsetzung ........................................................................................................ v 2.2 Forschungsfragen und Erläuterungen ...................................................................................... v 2.3 Forschungsstand, Vorkenntnisse und Motivation................................................................... vi 2.4 Methoden ............................................................................................................................... vii 1 HipHop in den USA 1.1 Der Cross-Bronx Expressway, Gangs und Arbeitslosigkeit ...................................................... 1 1.2 HipHop und seine Gründungsväter ........................................................................................ -

Recensie: Rammstein ****1/2

Recensie: Rammstein ****1/2 Sportpaleis Merksem donderdag 8 maart 2012 foto © Guido Karp Recensie: Een best of-optreden met alles erop en eraan. Rammstein staat voor spektakel live en ook nu weer werd alles uit de kast gehaald in het Sportpaleis. Een rubber bootje dat over de hoofden van de fans een toertje maakte tijdens Haifisch, vlammenwerpers tot in de nok, knallen, vuurwerk, het kon niet op. Ook de kinky kant kwam ruimschoots aan bod. "Buck dich“ dreef op sadisme (met drummer Christoph Schneider als meester en de rest als slaaf op handen en voeten geketend) en seks. Till Lindemann haalt een neppenis boven, een slang waarmee hij het publiek lange tijd natspuit Ook suggereert ie even anale seks. We begrijpen meteen waarom de site van de concertzaal het publiek erop attent wou maken dat de show minder geschikt zou zijn voor minderjarigen. In de tweede bisronde werd vervolgens een tweede penis, in kanonvorm bovengehaald tijdens "Pussy“ en mocht de zanger de eerste rijen een schuimfeestje bezorgen. Groots komt het sextet van Rammstein door het Sportpaleis via de brug het hoofdpodium op waarbij ze "Sonne“ aansnijden. Rammstein had in het begin van het optreden weliswaar last met de klank, het Duits was nauwelijks te verstaan, maar na enkele nummers was dat opgeklaard. Bij "Wollt Ihr Das Bett In Flammen Sehen“ komen synchroon met het gedrum vlammen uit het podium die de frontman in een cirkel rond zich heen ziet opgaan. Zowat het ganse podium is één metalen frame waaronder heel wat pyro afgestoken kan worden. Bij "Keine Lust“ mogen de C02-jets overuren kloppen. -

Jugendkulturen Und NS-Vergangenheit – Der Schmale Pfad Zwischen Provokation, Spiel, Inszenierung Und Erneuter Faszination Vom Punk Bis Zum Nazi-Rock

Martin Kersten, Jugendkulturen und NS-Vergangenheit – Der schmale Pfad zwischen Provokation, Spiel, Inszenierung und erneuter Faszination vom Punk bis zum Nazi-Rock PopScriptum Schriftenreihe herausgegeben vom Forschungszentrum Populäre Musik der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin aus: PopScriptum 5 – Rechte Musik, 70 - 89 Jugendkulturen und NS-Vergangenheit Der schmale Pfad zwischen Provokation, Spiel, Inszenierung und erneuter Faszination vom Punk bis zum Nazi-Rock Martin Kersten, Deutschland Einleitung «Rockmusik und Nazismus»: bis zum Beginn der neunziger Jahre war dies ein durchaus marginales Thema innerhalb des Gesamtdiskurses über Rock. Die Grundannahme, daß Mu- sik in der weitgefaßten Tradition des Rock'n'Roll als Ausdrucksform spezifisch jugendkultu- reller Praxis zwar rebellisch, unangepaßt und provokativ, aber niemals reaktionär oder gar nazistisch sein könne, stellte trotz vereinzelter Irritationen niemand ernsthaft in Frage. Diese stillschweigende Übereinkunft wurde nachhaltig erschüttert, als 1992 die ersten Berichte über Rockbands erschienen, deren Mitglieder überwiegend Skinheads waren und die mit ihren Texten und ihrem Auftreten unverhohlen rechtsextreme bis neonazistische Einstellun- gen zum Ausdruck brachten. Wenn man allein die Liedtexte der radikalsten Bands durchsieht, drängt sich einem sehr leicht der Gedanke auf, daß es sich hierbei um pure neonazistische Propaganda handelt, die sich die Musik als Medium gewählt hat. Viele der in diesen Texten anzutreffenden Floskeln sind tatsächlich eindeutig dem Sprachgebrauch der Nationalsozialisten entlehnt: «Wir haben uns dem Kampf um das Reich verschworen [...] und stehen wir im Kampfe auch allein, soll unser Glaube zum Sieg führen, wir werden das heilige Reich befreien, unser Sieg wird die Verräter zermürben» und «Deutschland, erwache» gröhlt Thomas Muncke, Sänger der Gruppe Tonstörung [1]; «Volk steh auf und Sturm brich los», zitieren Werwolf aus der Sportpalastrede von Joseph Goebbels [2] und die Musiker von Stör- kraft fühlen sich «hart wie Stahl», «stark wie deutsche Eichen» [3]. -

Tube the “New”

A PARENTS TELEVISION COUNCIL * SPECIAL REPORT * DECEMBER 17, 2008 The “New” Tube A Content Analysis of YouTube -- the Most Popular Online Video Destination PARENTS TELEVISION COUNCIL ™ L. Brent Bozell III Founder TABLE OF CONTENTS Tim Winter President Mark Barnes Executive Summary 1 Senior Consultant Background 3 Melissa Henson Director of Communications Study Parameters and Methodology 3 and Public Education Casey Bohannan Overview of Major Findings 6 Internet Communications Manager Results 8 Christopher Gildemeister Senior Writer/Editor Text Commentary 8 Michelle Jackson-McCoy, Ph.D. Director of Research Examples 9 Aubree Bowling Senior Entertainment Analyst Video Titles 11 Greg Rock Video Content 12 Ally Matteodo Amanda Pownall Sex 12 Justin Capers Oliver Saria Language 14 Entertainment Analysts Dan Isett Violence 15 Director of Public Policy Conclusion 16 Gavin Mc Kiernan National Grassroots Director Reference 17 Kevin Granich Assistant to the Grassroots Director Appendix 18 Glen Erickson Director of Corporate Relations About the PTC 19 LaQuita Marshall Assistant to the Director of Corporate Relations Patrick Salazar Vice President of Development Marty Waddell Senior Development Officer FOR MEDIA INQUIRIES Larry Irvin Nancy Meyer PLEASE CONTACT Development Officers Kelly Oliver or Megan Franko Tracy Ferrell CRC Public Relations Development Coordinator (703) 683-5004 Brad Tweten Chief Financial Officer Jane Dean Office and Graphics Administrator PTC’S HOLLYWOOD HEADQUARTERS 707 Wilshire Boulevard, Suite 2075 Los Angeles, CA 90017 • (213) 629-9255 www.ParentsTV.org® ® The PTC is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit research and education foundation. www.ParentsTV.org ® © Copyright 2008 – Parents Television Council 2 The “New” Tube A Content Analysis of YouTube – the Most Popular Online Video Destination EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Children are consuming more and more of their video entertainment outside the traditional confines of a television set. -

RAMMSTEIN 2012 Natourannouncement 11.14.2011

RAMMSTEIN CONFIRMS NORTH AMERICAN TOUR 2012 THE WORLD’S MOST EXPLOSIVE ROCK BAND RETURN TO NORTH AMERICA FOR 21 DATES IN SUPPORT OF THEIR RETROSPECTIVE ALBUM RELEASE “MADE IN GERMANY 1995-2011” LOS ANGELES, CA (November 14, 2011) - RAMMSTEIN , the Berlin-based band known for their incendiary live performances, will bring their brand new live production to North America this spring for 21 dates kicking off April 20 th in Ft. Lauderdale. Tickets for the tour, promoted by Live Nation, will go on sale beginning Friday, November 18 th and will be available at Ticketmaster.com, and LiveNation.com. Demand for Rammstein's pyrotechnic-laden performances has been so great in Europe, where they regularly play capacity level soccer stadiums, the band spent nearly a full decade without setting foot on North American shores. In December 2010, the sextet returned to North America for two sold out shows including a performance at Madison Square Garden. Rammstein followed with a 9-day trek of major North American cities in spring 2011. The Los Angeles Times described the live experience as “...epic stagecraft on a Wagnerian scale, several notches up from most arena rock.” The tour announcement comes on the heels of news of the band's first retrospective release, Made In Germany 1995 - 2011 , which will be available in North America (through a distribution deal between Universal Germany and Vagrant Records) on December 13. Rammstein recently released " Mein Land ," a new four-track digital single that features two new songs: the title track and "Vergiss uns Nicht " as well as remixes from BossHoss and Mogwai. -

Billboard-1997-07-19

$5.95 (U.S.), $6.95 (CAN.), £4.95 (U.K.), Y2,500 (JAPAN) IN MUSIC NEWS IBXNCCVR **** * ** -DIGIT 908 *90807GEE374EM002V BLBD 589 001 032198 2 126 1200 GREENLY 3774Y40ELMAVEAPT t LONG BEACH CA 90E 07 Debris Expects Sweet Success For Honeydogs PAGE 11 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT ADVERTISEMENTS RIAA's Berman JAMAICAN MUSIC SPAWNS Hit Singles Is Expected To DRAMATIC `ALTERNATIVES' Catapult Take IFPI Helm BY ELENA OUMANO Kingston -based label owner /artist manager Steve Wilson, former A &R/ Colvin, Robyn This story was prepared by Ad f , Mention "Jamaica" and most people promotion manager for Island White in London and Bill Holland i, think "reggae," the signature sound of Jamaica. "It means alternative to BY CHUCK TAYLOR Washington, D.C. that island nation. what's traditionally Jamaicans are jus- known as Jamaican NEW YORK -One is a seasoned tifiably proud of music. There's still veteran and the other a relative their music's a Jamaican stamp Put r ag top down, charismatic appeal on the music. The light p the barbet Je and its widespread basslines and drum or just enjoy the sunset influence on other beats sound famil- cultures and iar. But that's it. featuring: tfri musics. These days, We're using a lot of Coen Bais, Abrazas N all though, more and GIBBY FAHRENHEIT blues, funk, jazz, Paul Ventimiglia, LVX Nava BERMAN more Jamaicans folk, Latin, and a and Jaquin.liévaao are refusing to subsume their individ- lot of rock." ROBYN COLVIN BILLBOARD EXCLUSIVE ual identities under the reggae banner.