How to Get Away with Copyright Infringement: Music Sampling As Fair Use

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rns Over the Long Term and Critical to Enabling This Is Continued Investment in Our Technology and People, a Capital Allocation Priority

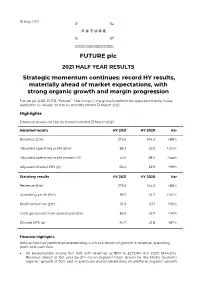

19 May 2021 FUTURE plc 2021 HALF YEAR RESULTS Strategic momentum continues: record HY results, materially ahead of market expectations, with strong organic growth and margin progression Future plc (LSE: FUTR, “Future”, “the Group”), the global platform for specialist media, today publishes its results for the six months ended 31 March 2021. Highlights Financial results for the six months ended 31 March 2021 Adjusted results HY 2021 HY 2020 Var Revenue (£m) 272.6 144.3 +89% Adjusted operating profit (£m)1 89.2 39.9 +124% Adjusted operating profit margin (%) 33% 28% +5ppt Adjusted diluted EPS (p) 65.4 32.9 +99% Statutory results HY 2021 HY 2020 Var Revenue (£m) 272.6 144.3 +89% Operating profit (£m) 59.7 24.7 +142% Profit before tax (£m) 56.9 27.1 +110% Cash generated from operations (£m) 85.9 35.7 +141% Diluted EPS (p) 40.7 21.8 +87% Financial highlights Robust first-half performance extending our track record of growth in revenue, operating profit and cash flow: An exceptionally strong first half, with revenue up 89% to £272.6m (HY 2020: £144.3m). Revenue ahead of last year by 21% on an organic2 basis, driven by the Media division’s organic2 growth of 30% and in particular digital advertising on-platform organic2 growth of 30% and eCommerce affiliates’ organic2 growth of 56%. US achieved revenue growth of 31% on an organic2 basis and UK revenues grew by 5% organically (UK has a higher mix of events and magazines revenues which were impacted more materially by the pandemic). -

![The Floozies Free Download [TSIS PREMIERE] Griz Announces All Good Records and Releases New Floozies Single As Free Download](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8281/the-floozies-free-download-tsis-premiere-griz-announces-all-good-records-and-releases-new-floozies-single-as-free-download-88281.webp)

The Floozies Free Download [TSIS PREMIERE] Griz Announces All Good Records and Releases New Floozies Single As Free Download

the floozies free download [TSIS PREMIERE] GRiZ Announces All Good Records And Releases New Floozies Single As Free Download. GRiZ who is one of the pioneers of the electro-soul and future funk sounds, along with artists like Pretty Lights and Gramatik, yet has managed to carve his own lane in the genre. The always impressive artist announced his own record label 2 years ago with the release of his most recent album Rebel Era which was put out as a free download as well as being on iTunes. Today, the artist is announcing a new chapter in his career with the closing of Liberated Music and the launch of All Good Records. This label, while still carrying out releases being freely available, is also a step in the direction of a full service record label as opposed to just an avenue for Grant (Griz) to distribute his own work. The label has two signed artists, mid west live funk duo The Floozies and Chicago based soul star and TSIS regular Manic Focus . You can now follow the new All Good Records on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook, but you should also visit the freshly launched website www.AllGoodRecords.com where you can hear a preview of a new GRiZ song which we can expect to see on his upcoming album Say It Loud that is dropping soon. Also to celebrate the launch, we have the latest single from the newly reformed labels' first release, The Floozies upcoming album Do Your Thing which will be released Jan 27th. We premiered "FNKTRP" and "Fantastic Love" from the group and now have an exclusive first listen of the song "She Ain't Yo Girlfriend" which captures the signature funky Floozies sound, yet is delivered in an extra sensual manner. -

On Probation

www.InsideVandy.com HUSTLER THETHURSDAY, NOVEMBER VANDERBIL 3, 2011 ★ 123RD YEAR, NO. 61 ★ THE VOICE OF VANDERBILT SINCE 1888 T VSG takes a stand On probation on sustainability KATIE KROG MORE FROM VSG STAFF REPORTER Inside the IFC judicial process BUDGET UPDATE Vanderbilt Student Govern- Rohan Batra, Vanderbilt ment Wednesday passed a Student Government treasurer, resolution to “actively support presented a monthly budget the highest level of sustainable update to VSG Wednesday building practices in all future night. building and renovation proj- According to Batra, VSG has ects it (VSG) has a voice in.” spent about $18,000 so far The resolution, presented by this fiscal year. VSG Environmental Affairs “This is in line with what Committee Chair Matt Bren- we’ve done in the past,” Batra nan, calls for a commitment to said. Silver LEED certification for all building projects costing over ANGEL TREE GIVES $5 million and to the highest BACK VSG announced Wednesday possible level of certification for that if you buy a present for all other projects. the VSG Angel Tree this De- In the Senate, the resolution cember, VUPD will forgive one passed unanimously without (and only one) of your campus debate. parking tickets. In the House, the resolution passed with an overwhelm- ing majority, with only three representatives voting against the resolution. Those opposed they have the highest possible to the resolution were Alumni level of certification. Area Representative David Di- According to Student Body panfilo, West House President President Adam Meyer, the Evan Werner and the proxy for Environmental Affairs Com- Alumni Lawn Area Represen- mittee consulted with several tative Kenny Tan. -

Relix Magazine

RELIX MAGAZINE Relix Magazine is devoted to the best in live music. Originally launched in 1974 to connect the Grateful Dead community, Relix now features a wide spectrum of artists including: Phish, My Morning Jacket, Beck, Jack White, Leon Bridges, Ryan Adams, Tedeschi Trucks Band, Chris Stapleton, Tame Impala, Widespread Panic, Fleet Foxes, Joe Russo’s Almost Dead, Umphrey’s McGee and plenty more. Relix also offers a unique angle on the action with sections such as: Tour Diary, Behind The Scene, Global Beat, Track By Track, On The Verge and My Page as well as extensive reviews of live shows and recorded music. Each of our 8 annual issues covers new and established artists and comes with a free CD and digital downloads. TOTAL READERSHIP: 360,000+ MONTHLY PAGEVIEWS: 1.6 Million+ MONTHLY UNIQUE USERS: 280,000+ EMAIL SUBSCRIBERS: 225,000+ SOCIAL MEDIA FOLLOWERS: 410,000+ RELIX MEDIA GROUP Relix Media Group is a multifaceted, innovative, open-minded and creative resource for the live music scene. We are a passionate mix of writers, photographers, videographers, event coordinators, musicians and industry professionals. Above all, we are music lovers. Our mission is to seek out exciting, innovative performers and foster the live music community by connecting with the people who matter most: the fans. Since our earliest inception, we have opened doors for the sonically curious and sought to represent the voice of the concert community. Relix Media Group Info • relix.com • jambands.com • 3,700,000 total impressions • 375,000 total unique visitors -

MUSICRADAR.COM (12/6) Epic-Guitar-Performances-568156

MUSICRADAR.COM (12/6) http://www.musicradar.com/news/guitars/rival-sons-scott-holiday-talks-jimmy-page-riff-writing-and- epic-guitar-performances-568156 Rival Sons' Scott Holiday talks Jimmy Page, riff writing and epic guitar performances If Head Down were Rival Sons' debut album and not their third release, we'd be heralding the unexpected arrival of a bright new talent, and possibly even an important one, a group that manages to take their cues from firmly established blues-rock paradigms while proving there's still rich, untapped pockets to be mined. Oh, hell, let's dispense with the formalities and give it up for this California four-piece (singer Jay Buchanan, guitarist Scott Holiday, bassist Robin Everhart and drummer Mike Miley), who attack well- worn forms – there's also splashes of soul, funk and head-spinning psychedelia, for good measure – with a zeal that borders on audacity. The grooves are deep and the vocals are of the chest-beating variety, but the real star of the show is guitarist Holiday. On the album's 13 exhilarating cuts, he hits with with tectonic force, creating rich tapestries of sound that burst wide open with style, imagination and an infectious, warped charm. We caught up with Holiday the other day to chat about his spunky approach to guitar playing, his many axes and sonic toys, and to find out how he felt rubbing shoulders with a new fan, another six- string slinger who goes by the name Jimmy Page. So Jimmy Page likes your band. That's got to feel good. -

22 Essential Arranging Tips | Musicradar Page 1 of 5

22 essential arranging tips | MusicRadar Page 1 of 5 THE NO.1 WEBSITE FOR MUSICIANS MORE Gear reviews Tuition Best audio interfaces 2018 Best electric guitars 2018 Free samples Learn Ableton Live Tuition > Tech > 22 essential arranging tips 22 essential arranging tips By The MusicRadar team February 11, 2008 Tech Turn your musical ideas into fully-formed tunes The arrange page in your DAW could soon be as busy as this one. Arranging can broadly be defined as the process of transforming a collection of musical ideas into a complete track. It can involve everything from writing harmonies, re-arranging parts, adding parts, removing parts, planning the structure of a song or even adding effects from time to time. If there's one absolute truth about arranging, though, it's that it's the stage where you have to stop making excuses and start making firm decisions, whether these be about which parts to leave in or out, where to put them, or whether you need to add a whole new part altogether. Consequently, for many, arranging is also where music making stops being fun and creative and starts feeling a bit too much like pressure and hard work. This needn't be the case, though - with all the power and versatility that modern technology gives us, the possibilities are endless and the process can be relatively painless. Here are our 22 top arranging tips: 1. Listen, listen, listen. There's absolutely no substitute for experience, so be sure to analyse the arrangements of all your favourite tracks. Listen to what other producers have done and try to figure out why it works (or why it doesn't work, as the case may be...). -

©2011 Campus Circle • (323) 939-8477 • 5042 Wilshire Blvd

©2011 CAMPUS CIRCLE • (323) 939-8477 • 5042 WILSHIRE BLVD., #600 LOS ANGELES, CA 90036 • WWW.CAMPUSCIRCLE.COM • ONE FREE COPY PER PERSON TIME “It’s a heightened, almost hallucinatory sensual experience, and ESSENTIAL VIEWING FOR SERIOUS MOVIEGOERS.” RICHARD CORLISS THE NEW YORK TIMES “A COSMIC HEAD MOVIE OF THE MOST AMBITIOUS ORDER.” MANOHLA DARGIS HOLLYWOOD WEST LOS ANGELES EXCLUSIVE ENGAGEMENTS START FRIDAY, MAY 27 at Sunset & Vine (323) 464-4226 at W. Pico & Westwood (310) 281-8233 FOX SEARCHLIGHT FP. (10") X 13" CAMPUS CIRCLE - 4 COLOR WEDNESDAY: 5/25 ALL.TOL-A1.0525.CAM CC CC JL JL 4 COLOR Follow CAMPUS CIRCLE on Twitter @CampusCircle campus circle INSIDE campus CIRCLE May 25 - 31, 2011 Vol. 21 Issue 21 Editor-in-Chief 6 Yuri Shimoda [email protected] Film Editor 4 14 [email protected] Music Editor 04 FILM MOVIE REVIEWS [email protected] 04 FILM PROJECTIONS Web Editor Eva Recinos 05 FILM DVD DISH Calendar Editor Frederick Mintchell 06 FILM SUMMER MOVIE GUIDE [email protected] 14 MUSIC LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE Editorial Interns Intimate and adventurous music festival Dana Jeong, Cindy KyungAh Lee takes place over Memorial Day weekend. 15 MUSIC STAR WARS: IN CONCERT Contributing Writers Tamea Agle, Zach Bourque, Kristina Bravo, Mary Experience the legendary score Broadbent, Jonathan Bue, Erica Carter, Richard underneath the stars at Hollywood Bowl. Castañeda, Amanda D’Egidio, Jewel Delegall, Natasha Desianto, Stephanie Forshee, Jacob Gaitan, Denise Guerra, Ximena Herschberg, 15 MUSIC REPORT Josh -

Production Project Rundown

Production Project Rundown July 2015: National Guard (Hero Video) – Fort Drum, NY § Camera Operator May 2015: NBC – The Voice (Season 8, Episode 25) § Production Assistant § Transportation § Client: NBC Corridor 94 (Promotional Piece) § Producer § Director of Photography § Editor § Client: Corridor 94 March 2015: 2015 Show Reel § Edited 2015 showcase (promotional piece.) February 2015: Up/Down – MC Friendly music video – 1/27/15 § Camera operator § Assistant Director § Client: Young Heavy Souls Inc. January 2015: Womp Romp live in Kalamazoo – 1/17/15 § Produced event recap § Producer, cinematographer, editor § Client: TBA Pro November 2014: Womp Romp live in Muskegon – 11/21/14 § Produced event recap § Producer, cinematographer, editor § Client: TBA Pro Halloween on Ionia (event coverage) – 11/1/14 § Cinematographer for promotional piece § Client: Willy Wompa (Artist) October 2014: Paper Diamond live in MT. Pleasant – 10/30/14 § Produced event recap § Cinematographer § Editor § Client: Layer Cake Entertainment Music video 10/17/14 – 10/27/14 § Belle Ghoul - Around for the weekend § Edit only § Client: Elefant Records, Belle Ghoul Pretty Lights Music live in Kalamazoo 10/6/14 – 10/12/14 § Event recap § Edit only § Client: Layer Cake Entertainment Kelsey & Jim Kosiboski wedding 10/4/14 § Producer § Director § Cinematographer § Editor § Client: Kelsey & Jim Kosiboski September 2014: Music video shoot (Skee-Town Stylee) – 9/27/14 § Producer § Cinematographer § Editor § Client: TBA Pro, Skee – Town Stylee Womp Romp live in Grand Rapids – 9/26/14 § Produced event recap § Cinematographer § Editor § Cllient: TBA Pro History Channel (Cars & Stripes) – 9/14/14 § Production assistant Layer Cake Entertainment Showcase – 9/12/14 § Cinematographer § Editor § Client: Layer Cake Entertainment August 2014: Creative Turntable kickstarter – 8/12/14 § Produced kickstarter video for creative turntable led slipmats. -

C&C Drum Company Player Date Kit | Drum Reviews | Musicradar

C&C Drum Company Player Date Kit | Drum Reviews | MusicRadar 2/15/13 3:21 AM A Future Site ! musicradar. Guitarist Guitar Techniques Total Guitar Computer Music Future Music Rhythm Search MusicRadar Home Guitars Acoustic Bass Drums Tech DJ Drums News Reviews Tuition Video Forum Samples iPad/iPhone Apps Magazines MusicRadar Partners Jake Bugg – Slide away with the FG700MS Jake Bugg performed in BBC’s Radio 1 live lounge on ... Also related to this article C&C Drums Company Custom Kit Flaxwood CC-H CC Custom Ovation Celebrity CC074 As with the kit that inspired them, Player Date drums are made from mahogany (albeit hand-built rather than mass produced Related from other sources C&C Drum Company 3 57 C&C Drum Company Player official site Date Kit Like Can this off-the-shelf kit keep the custom charm? More on this topic Add Comment Adam Jones (Rhythm) January 15, 2013, 14:33 GMT Ludwig Brought to you by Since its quiet inception over two decades ago, C&C Drum Company has remained determinedly low-key, operating on little more than a word-of- mouth basis. This four-piece Player Date on review is from C&C's first ever range of production (off-the-shelf) kits. Based in Gladstone, Missouri and run by Bill Cardwell and his son Jacob, C&C More from Drums MusicRadar Rating (formerly C&C Custom Drums) has is known worldwide for building beautiful- looking and classic-sounding drums, but can its off-the-shelf kits maintain that Animal Custom 2012 reputation? Series Kit Verdict Build There is an unpretentious If the Player Date bears any resemblance to Ludwig's Club Date kit reviewed a and honest feel to this kit few issues ago, let's just say that Bill Cardwell had been developing his that is appealing. -

Future Publishing Statement for IPSO – April 2016

Future Publishing Statement for IPSO – April 2016 About Future Future plc is an international publishing and media group, and a leading digital company. Celebrating over 30 years in business, Future was founded in 1985 with one magazine – we now create over 200 print publications, apps, websites and events through operations in the UK, US and Australia. The company employs approximately 500 employees. Future’s leadership structure is outlined in Appendix C (the structure has changed slightly since our last statement in December 2015). Our portfolio covers consumer technology, games/entertainment, music, creative/design and photography. 48 million users globally access Future’s digital sites each month, we have over 200,000 digital subscriptions worldwide, and a combined social media audience of 20+ million followers (a list of our titles/products can be found under Appendix A). For the purpose of this statement, Future’s ‘responsible person’ is Nial Ferguson, Content Director, Media. Future’s editorial standards Through our expertise in five portfolios, Future produces engaging, informative and entertaining content to a high standard. The business is driven by a core strategy - ‘Content that Connects’ - that has been in place since 2014 (see Appendix B). This puts content at the heart of what we do, and is an approach we reiterate through staff communication. In creating content that connects, Future takes all reasonable and appropriate steps to verify what we publish. Such steps include double sourcing where necessary, and rigorous scrutiny of information and sources to ensure the accuracy of the articles we publish. Editorial process for contentious issues involves second reading by editorial. -

Future Plc Today Announces the Launch of Fourfourtwo Turkey

Future Plc today announces the launch of FourFourTwo Turkey FourFourTwo Turkey entered the market in 2006, and will continue its path with a new partner – Lobby Lobos Advertising 17th February 2020 – Future Plc, The world's largest English-speaking football magazine, FourFourTwo, has expanded with the exciting arrival of its new partner in Turkey: Lobby Lobos. After initially entering the Turkish market in 2006, FourFourTwo has been followed with admiration ever since, becoming a leader of the football print media sector in Turkey. Future Plc has a reputation for thinking ahead of its competitors and adapting in the digital world – and as such, they have paved the way for a revamped FourFourTwo Turkey to develop the FourFourTwo brand in a football-obsessed nation of 83 million people. Together, Future and Lobby Lobos Advertising will integrate e-commerce solutions and establish dialogue between teams. Editor-in-chief, Can Elmas said: “FourFourTwo Turkey has always been the magazine everybody considered to be a guiding light. But in the same way that other football titles went through, it faced significant problems during the digitisation process. We have since agreed to a new economic model that will be an example for all in the new era of FourFourTwo Turkey and Future Plc. In a world that is becoming more and more digital, we will lead our competitors again.” FourFourTwo Turkey aims to become the first audio-magazine in Turkey, too, working to establish a new relationship with football fans. The editorial department has created the ‘FourFourTwo Reserve Team’, which aims to bring new sports journalists and writers aged 18-24 into the industry and showcase their work to a wider audience. -

Qello to Present Headcount 10Th Anniversary Benefit Concert with Bob Weir & Ratdog Plus Special Guests

For Immediate Release: Qello to Present HeadCount 10th Anniversary Benefit Concert with Bob Weir & Ratdog plus Special Guests NEW YORK - Bob Weir and Ratdog will join a slew of guest musicians at the HeadCount 10th Anniversary Benefit Concert at the Brooklyn Bowl in Brooklyn, NY on June 4th. The event will also be the official Kickoff Party for Mountain Jam, a festival that begins the next day at Hunter Mountain in upstate New York and runs through the weekend. HeadCount founder Marc Brownstein of The Disco Biscuits, Brendan Bayliss of Umphrey’s McGee, Eric Krasno of Soulive and Lettuce, and Lettuce horn players Ryan Zoidis and Eric Bloom will all make appearances, with more special guests to be announced. Qello, the world’s leading on-demand streaming service for full-length HD concert films and music documentaries, will be the exclusive presenting sponsor of the event, with Grain Audio, iCitizen, Mashable, Apple and Eve and Ticketfly also serving as sponsors. Tickets go on sale to the public on Tuesday April 22nd at noon at BrooklynBowl.com. An exclusive pre-sale for Mountain Jam ticketholders and friends of official event hosts begins today. More information can be found at www.HeadCount.org/benefit. “It’s going to be big fun,” said Weir, one of HeadCount’s founding board members. “It’s always great to collaborate with other musicians, and HeadCount’s tenth anniversary is a true reason to celebrate.” Less than 24 hours after the concert, the tenth annual Mountain Jam will begin at Hunter Mountain. Weir and Ratdog will appear on Friday, June 6th, and Umphrey’s McGee will perform Thursday the 5th.