Defending the Promise: Maintaining a Place from Which to Act in the Age of Climate Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City Space and Urban Identity a Post-9/11 Consciousness in Australian Fiction 2005 to 2011

City Space and Urban Identity A Post-9/11 Consciousness in Australian Fiction 2005 to 2011 By Lydia Saleh Rofail A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English. Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney 2019 Declaration of Originality I affirm that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and I certify and warrant to the best of my knowledge that all sources of reference have been duly and fully acknowledged. Lydia Saleh Rofail i Abstract This thesis undertakes a detailed examination of a close corpus of five Australian literary novels published between 2005 and 2011, to assess the political, social, and cultural implications of 9/11 upon an urban Australian identity. My analysis of the literary city will reveal how this identity is trapped between layers of trauma which include haunting historical atrocities and inward nationalism, as well as the contrasting outward pull of global aspirations. Dead Europe by Christos Tsiolkas (2005), The Unknown Terrorist by Richard Flanagan (2006), Underground by Andrew McGahan (2006), Breath by Tim Winton (2008), and Five Bells by Gail Jones (2011) are uniquely varied narratives written in the shadow of 9/11. These novels reconfigure fictional notions of Australian urbanism in order to deal with fears and threats posed by 9/11 and the fallout that followed, where global interests fed into national concerns and discourses within Australia and resonated down to local levels. Adopting an Australia perspective, this thesis contextualises subsequent traumatic and apocalyptic trajectories in relation to urbanism and Australian identity in a post-9/11 world. -

Genie Energy Ltd. 2016 Annual Report

GENIE ENERGY LTD. 2016 ANNUAL REPORT Fellow Stockholders, Throughout 2016, Genie made signifi cant investments in growth opportunities and took additional steps to improve its strategic position for 2017 and beyond. We are now well situated to reap the benefi ts of these decisions as we continue to execute on our growth strategies. Genie Retail Energy captured robust margins and implemented operating effi ciencies to achieve strong bottom line growth during the past year. In the fourth quarter, we closed on the acquisition of Town Square Energy which signifi cantly expanded our geographic reach, added to our meter and RCE bases, and provided us with additional marketing savvy through new meter acquisition channels. As a result of the acquisition, Genie Retail is poised to further expand its meter base and deliver strong bottom-line results. Looking ahead, the retail energy space presents additional expansion opportunities. Here in the US, we are working to enter additional deregulated markets while scouting for additional acquisition opportunities. Globally, competitive energy supply is also a signifi cant growth sector. We are closely monitoring developments in several overseas markets to identify opportunities that meet our expansion criteria. Genie Retail Energy also made signifi cant progress to address legal and regulatory challenges. We enter 2017 with signifi cantly less uncertainty in those areas compared to the year ago. At GOGAS, we have narrowed our operational focus to our Afek exploratory oil project in Northern Israel, suspending operations at other units and decommissioning our AMSO oil shale project in Colorado. Afek has drilled fi ve wells in the southern portion of its license area and completed well fl ow tests on two of those wells. -

The Israeli Wind Energy Industry in the Occupied Syrian Golan

Flash Report Greenwashing the Golan: The Israeli Wind Energy Industry in the Occupied Syrian Golan March 2019 Introduction 2 Methodology 2 The Israeli Wind Energy Industry 2 Targeting the Syrian Golan for Wind Farm Construction 3 About the Occupied Syrian Golan 5 Commercial Wind Farms in the Syrian Golan 6 Al-A’saniya Wind Farm 6 Valley of Tears (Emek Habacha) Wind Farm 7 Ruach Beresheet Wind Farm 10 Clean Wind Energy (ARAN) Wind Farm 10 Conclusion 12 Annex I: Aveeram Ltd. company response 13 Introduction For each farm we expose the involvement of international and Israeli companies which Though neither sun nor wind are finite re- include, Enlight Renewable Energy, Energix sources, their exploitation for electricity gen- Group and General Electric, among others. eration is not without material constraints. Green energy requires favorable geographic The report argues that the emergence of this conditions and extensive swathes of land. sector is a case of greenwashing: while touted In the Israeli context, the emergence of the as the “green solution” to Israel’s national en- green energy industry over the past decade, ergy requirements, the growth of this indus- has been inextricably tied to Israeli control try in the occupied Golan is in fact an inherent over Palestinian and Syrian land. part of the expansion of Israel’s control and presence in the Syrian Golan. Previous research by Who Profits demon- strated the centrality of Palestinian land to Methodology the development of Israeli solar energy.1 We This flash report is based on both desk and revealed that the Jordan Valley in the oc- field research. -

Pommy Media Causing a Stir in Australia

Pommy media causing a stir in Australia blogs.lse.ac.uk/polis/2014/10/25/pommy-media-causing-a-stir-in-australia/ 2014-10-25 The Australian media landscape is becoming a little heated as recent British entrants continue to carve out new digital territory in the Land Down Under. Colleen Murrell reports on the increasing levels of distrust both between the players – The Australian versions of The Guardian, the Daily Mail and the BBC – and between those players and the tough local media groups, Fairfax Media and Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. Australia. Last Thursday the chief executive of Guardian Media Group, Andrew Miller, gave the annual Polis lecture in London in which he didn’t appear to welcome the BBC’s expansion into Australia. He disputed that this should be a “core part” of the BBC’s mission and said it did not “benefit UK licence fee payers or meet the requirement of the BBC to provide news in parts of the world where there are limited alternatives”. He added. “It threatens a distortion that is not in the interests of audiences or other UK news providers”. Alluding to the ‘licence fee payers’ is disingenuous as the expanded website venture isn’t funded by the licence fee but is a commercial enterprise that will be financed by advertising. It is therefore the second part of the allegation – that it is not in the interests of “other UK news providers” – that really bothers the Guardian. Earlier this month the BBC recruited The Sydney Morning Herald’s Chief of Staff Wendy Frew, showing that it is committed to serious newsgathering. -

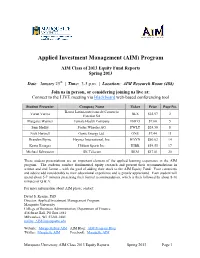

Applied Investment Management (AIM) Program

Applied Investment Management (AIM) Program AIM Class of 2013 Equity Fund Reports Spring 2013 Date: January 25th | Time: 3-5 p.m. | Location: AIM Research Room (488) Join us in person, or considering joining us live at: Connect to the LIVE meeting via Blackboard web-based conferencing tool Student Presenter Company Name Ticker Price Page No. Banco Latinoamericano de Comercio Varun Varma BLX $22.57 2 Exterior SA Margaret Wanner Female Health Company FHCO $7.60 5 Sam Sladky Foster Wheeler AG FWLT $24.50 8 Nick Hartnell Genie Energy Ltd. GNE $7.44 11 Brandon Byrne Haynes International, Inc. HAYN $50.02 14 Kevin Kroeger Hibbett Sports Inc. HIBB $54.55 17 Michael Schwoerer SK Telecom SKM $17.01 20 These student presentations are an important element of the applied learning experience in the AIM program. The students conduct fundamental equity research and present their recommendations in written and oral format – with the goal of adding their stock to the AIM Equity Fund. Your comments and advice add considerably to their educational experience and is greatly appreciated. Each student will spend about 5-7 minutes presenting their formal recommendation, which is then followed by about 8-10 minutes of Q & A. For more information about AIM please contact: David S. Krause, PhD Director, Applied Investment Management Program Marquette University College of Business Administration, Department of Finance 436 Straz Hall, PO Box 1881 Milwaukee, WI 53201-1881 mailto: [email protected] Website: MarquetteBuz/AIM AIM Blog: AIM Program Blog Twitter: Marquette AIM Facebook: Marquette AIM Marquette University AIM Class 2013 Equity Reports Spring 2013 Page 1 Banco Latinoamericano de Comercio Exterior SA (BLX) January 25, 2013 Varun Varma International Financial Services Banco Latinoamericano de Comercio Exterior SA (NYSE:BLX), known as Bladex, is a supranational bank originally established by the Central Banks of Latin America (LatAm) and Caribbean countries to promote trade finance in the Region. -

Submission to the Working Group on Private Military and Security Companies in Immigration Enforcement

Submission to the Working Group on Private Military and Security Companies in Immigration Enforcement 21 July 2020 Convicted New Zealander experiences with Serco security company, law and border enforcement personnel in immigration detention and s501 deportation from Australia Rebecca Powell, Managing-Director and PhD Candidate, The Border Crossing Observatory, Monash University. Introduction and background This submission has been developed from my research on the deportation of convicted New Zealanders from Australia under Section 501 –visa cancellation and refusal on character grounds – of the Commonwealth Migration Act 1958.1 My research is focused from when legislative amendments were made to s501 in December 2014 resulting in a steep increase in the number of convicted non-citizens experiencing visa cancellation and deportation from Australia under s501 by 1,100% (Australian Government, Department of Home Affairs, Visa Statistics website) following the introduction of mandatory visa cancellation provisions.2 Since these amendments, New Zealanders are the largest nationality group deported from Australia. From December 2014 to July 2020, the visas of 2,877 New Zealanders have been cancelled on character grounds under s501 (Australian Border Force 2020). From 2015-2018, 1,144 New Zealanders have been deported from Australia (Department of Home Affairs). New Zealanders continue to be consistently recorded as the largest or second largest nationality group in Australia’s immigration detention network from August 2015, whereas they were not even recorded as a nationality group before this time because their numbers were so low (Australian Government, Department of Home Affairs, Immigration Detention Statistics website). An analysis I have conducted of New Zealander visa cancellation review cases at the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) reveals that over 70% of these cases 1 See, ‘Risk and human rights in the deportation of convicted non-citizens from Australia to New Zealand’ The Border Crossing Observatory. -

GRATTAN Institute

GRATTAN Institute The course of COVID-19 in Australia Submission to the Senate Inquiry into the Australian Government's response to the COVID-19 pandemic June 2020 Stephen Duckett, Hal Swerissen, Will Mackey, Anika Stobart and Hugh Parsonage Grattan Institute 2020 1 Overview The SARS-CoV-2 virus (coronavirus) galvanised a public health shutdowns, and the need for vigilance and swift responses to response not seen in Australia for more than a century. To prevent its outbreaks. spread, and the disease it causes, COVID-19, social and economic activity was shut down. Australia emerged with low numbers of Choices are being made about how and when the lockdown will be deaths, and a health system which coped with the outbreak. eased, with each state and territory taking a different path. While the virus continues to circulate, there will be a risk of a second wave. Australia’s response passed through four stages – containment, reassurance amid uncertainty, cautious incrementalism, and then In this report we describe a model developed at Grattan Institute escalated national action – as the gathering storm of the pandemic which simulates the risks of different relaxation strategies, and we became more apparent. draw some lessons for the health system. We show that some strategies, such as reopening schools, involve some risk of There were four key successes in the response: cooperative outbreaks, but these outbreaks most likely can be controlled. We governance informed by experts (most notably seen in the highlight those strategies which are riskier, particularly reopening establishment of the National Cabinet), closure of international large workplaces. -

Breaking News

BREAKING NEWS First published in Great Britain in 2018 by Canongate Books Ltd, 14 High Street, Edinburgh EH1 1TE canongate.co.uk This digital edition first published in 2018 by Canongate Books Copyright © Alan Rusbridger, 2018 The moral right of the author has been asserted British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library ISBN 978 1 78689 093 1 Export ISBN 978 1 78689 094 8 eISBN 978 1 78689 095 5 To Lindsay and Georgina who, between them, shared most of this journey Contents Introduction 1. Not Bowling Alone 2. More Than a Business 3. The New World 4. Editor 5. Shedding Power 6. Guardian . Unlimited 7. The Conversation 8. Global 9. Format Wars 10. Dog, Meet Dog 11. The Future Is Mutual 12. The Money Question 13. Bee Information 14. Creaking at the Seams 15. Crash 16. Phone Hacking 17. Let Us Pay? 18. Open and Shut 19. The Gatekeepers 20. Members? 21. The Trophy Newspaper 22. Do You Love Your Country? 23. Whirlwinds of Change Epilogue Timeline Bibliography Acknowledgements Also by Alan Rusbridger Notes Index Introduction By early 2017 the world had woken up to a problem that, with a mixture of impotence, incomprehension and dread, journalists had seen coming for some time. News – the thing that helped people understand their world; that oiled the wheels of society; that pollinated communities; that kept the powerful honest – news was broken. The problem had many different names and diagnoses. Some thought we were drowning in too much news; others feared we were in danger of becoming newsless. -

Genie Energy Ltd (NYSE: GNE, GNEPRA)

Genie Energy Ltd (NYSE: GNE, GNEPRA) Investor Presentation August 2014 Safe Harbor Statement This presentation contains forward-looking statements. Statements that are not historical facts are forward-looking statements and such forward-looking statements are statements made pursuant to the Safe Harbor Provisions of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995. Examples of forward-looking statements include: • statements about Genie’s and its divisions’ future performance; • projections of Genie’s and its divisions’ results of operations or financial condition; • statements regarding Genie’s plans, objectives or goals, including those relating to its strategies, initiatives, competition, acquisitions, dispositions and/or its products; and • expectations concerning the permitting, timing and development of Genie’s shale oil projects. Words such as "believe," "anticipate," "plan," "expect," "intend," "target," "estimate," "project," "predict," "forecast," "guideline," "aim," "will," "should," “likely,” "continue" and similar expressions are intended to identify forward-looking statements but are not the exclusive means of identifying such statements. Readers are cautioned not to place undue reliance on these forward- looking statements and all such forward-looking statements are qualified in their entirety by reference to the following cautionary statements. Forward-looking statements are based on Genie’s current expectations, estimates and assumptions and because forward- looking statements address future results, events and conditions, they, by their very nature, involve inherent risks and uncertainties, many of which are unforeseeable and beyond the Genie’s control. Such known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors may cause Genie’s actual results, performance or other achievements to differ materially from the anticipated results, performance or achievements expressed, projected or implied by these forward-looking statements. -

AUSTRALIA, ADANI and the WANGAN and JAGALINGOU the Material Costs of Claiming International Human Rights STEPHEN M YOUNG*

THE MATERIAL COSTS OF CLAIMING INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS: AUSTRALIA, ADANI AND THE WANGAN AND JAGALINGOU The Material Costs of Claiming International Human Rights STEPHEN M YOUNG* This article presents a materialist account of Indigenous peoples’ international legal human rights claims. It argues that appeals to the global legal system as well as pluralistic approaches to Indigenous peoples’ rights depend on international law to make a convincing case and yet fail to account for the material construction of human rights claimants as subjects of international law. To explain this intervention, this article theorises that when international human rights law and national laws clash, human rights claimants constitute and transform themselves into international legal subjects and become identifiable Indigenous peoples. In support of this international legal constructivist approach to Indigenous peoples’ human rights claims, this article re-articulates the development of Indigenous peoples as subjects that emerged from international law and then examines the development of Australia’s native title regime. An exposition of international and then state laws reveals that the codification of different standards for participation enables those who subject themselves to international law as Indigenous peoples to claim human rights. It then provides a case study on the Wangan and Jagalingou Family Council, which constructed itself as Indigenous peoples to assert human rights, as they engage with Australia’s native title regime in the case against Adani Mining Pty Ltd’s Carmichael Coal Mine and Rail Project. A central aspect of this argument is that becoming identifiable Indigenous peoples through claiming human rights provides benefits as well as potentially deleterious political, economic and legal costs. -

Assessment of Plans and Progress on US Bureau of Land Management Oil Shale RD&D Leases in the United States Peter M

Assessment of Plans and Progress on US Bureau of Land Management Oil Shale RD&D Leases in the United States Peter M. Crawford, Christopher Dean, and Jeffrey Stone, INTEK, Inc. James C. Killen, US Department of Energy Purpose This paper describes the original plans, progress and accomplishments, and future plans for nine oil shale research, development and demonstration (RD&D) projects on six existing RD&D leases awarded in 2006 and 2007 by the United States Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to Shell, Chevron, EGL (now AMSO), and OSEC (now Enefit American, respectively); as well as three pending leases to Exxon, Natural Soda, and AuraSource, that were offered in 2010. The outcomes associated with these projects are expected to have global applicability. I. Background The United States is endowed with more than 6 trillion barrels of oil shale resources, of which between 800 billion and 1.4 trillion barrels of resources, primarily in Colorado, Wyoming, and Utah may be recoverable using known and emerging technologies. (Figure 11) These resources represent the largest and most concentrated oil shale resources in the world. More than 75 percent of these resources are located on Federal lands managed by the Department of the Interior. BLM is responsible for making land use decisions and managing exploration of energy and mineral resource on Federal lands. In 2003, rising oil prices and increasing concerns about the economic costs and security of oil imports gave rise to a BLM oil shale research, development and demonstration (RD&D) program on lands managed by BLM in Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming. -

UPHOLDING the AUSTRALIAN CONSTITUTION

UPHOLDING the AUSTRALIAN CONSTITUTION Volume 29 Proceedings of the 29th Conference of The Samuel Griffith Society Novotel Perth Langley 221 Adelaide Terrace, Perth, Western Australia 25-27 August 2017 2018 by The Samuel Griffith Society. All rights reserved. Published 2018 by The Samuel Griffith Society PO Box 13076, Law Courts VICTORIA 8010 World Wide Web Address: http://www.samuelgriffith.org.au Printed by: McPherson’s Printing Pty Ltd 76 Nelson Street, Maryborough, Vic 3465 National Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data: Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume 29 Proceedings of The Samuel Griffith Society ISSN 1327-1539 ii Contents Introduction Eddy Gisonda v The Zeitgeist and the Constitution The 2017 Sir Harry Gibbs Memorial Oration The Honourable P. A. Keane ix 1. Fake News, Federalism and the Love Media Chris Kenny 1 2. The Unconstitutionality of Outlawing Political Opinion Augusto Zimmermann 17 3. Government not Gridlock Tony Abbott 49 4. In Defence of the Senate James Paterson 57 5. Western Australia and the GST Mike Nahan 69 6. Western Australia and Secession David Leyonhjelm 79 iii 7. Workplace Rights and the States Daniel White 89 8. Causes of Coming Discontents: The European Union as a Role Model for Australia? Neville Rochow 103 9. Federalism and the High Court in the 21 st Century The Honourable Robert Mitchell 181 10. Federalism and the Principle of Subsidiarity Michelle Evans 201 11. Passing the Buck The Honourable Wayne Martin 227 12. The Aboriginal Question: Enough is Enough! John Stone 273 13. A Colour-blind Constitution Keith Wolahan 319 14. Recognition Roulette The Honourable Nicholas Hasluck 337 Contributors 355 iv Introduction Eddy Gisonda The Samuel Griffith Society held its 29 th Conference on the weekend of 25 to 27 August 2017, in the city of Perth, Western Australia.