GRATTAN Institute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flattening the Curve: 3/9/2020 We’Re All in This Together, Together We Can Stop the Spread and We All Have a Role to Play

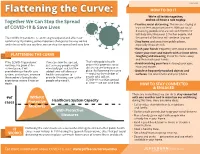

3/23/2020 HOW TO DO IT Flattening the Curve: 3/9/2020 We’re all in this together, Together We Can Stop the Spread and we all have a role to play. • Practice social distancing. This means staying at of COVID-19 & Save Lives least six feet away from others. Without social distancing, people who are sick with COVID-19 will likely infect between 2-3 other people, and The COVID-19 pandemic is continuing to expand and affect our the spread of the virus will continue to grow. community. By making some important changes to the way we live • Stay home and away from public places, and interact with one another, we can stop the spread and save lives. especially if you are sick. • Wash your hands frequently with soap and water. • Cover your nose and mouth with a tissue when FLATTENING THE CURVE coughing and sneezing, throw the tissue away and then wash your hands. If the COVID-19 pandemic If we can slow the spread, That’s why public health orders that promote social • Avoid touching your face including your eyes, continues to grow at the just as many people might nose and mouth. current pace, it will eventually get sick, but the distancing are being put in overwhelm our health care added time will allow our place. By flattening the curve • Disinfect frequently touched objects and system, and in-turn, increase health care system to — reducing the number of surfaces, like door knobs and your phone. the number of people who provide lifesaving care to the people who will get experience severe illness or people who need it. -

The Critical Importance of Expert Statistical Input

Sent to the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet 18 August 2020 A proposal to enhance Australia’s capability to manage epidemics The critical importance of expert statistical input 1 2 Nicholas Fisher and Dennis Trewin Executive summary Given the high level of global mobility, pandemics are likely to be more frequent, and with potentially devastating consequences for the Australian community and its way of life. Whilst parts of Australia are experiencing a second wave of COVID-19, the country is in relatively better shape than most others. The number of people who have died or been seriously ill as a consequence of the virus, whilst tragically high, is nonetheless comparable with most of the best-performing countries. That said, we believe there is a critical need for strategic statistical oversight of the whole process of anticipating, managing and learning from the current pandemic to improve the quantitative information and advice provided to policy makers. This proposal outlines quantitative aspects of a plan to enable Australia to deal more efficiently and effectively with future such events, thus enhancing both the social and the economic welfare of its people. Indeed, expeditious action may well assist materially in managing possible future waves of the current pandemic, and its aftermath. A dispassionate assessment of Australia’s health and economic response to the pandemic over the last six months reveals some very significant inadequacies in the data, statistical analysis and interpretation used to guide Australia’s preparations and actions. Data to answer some of the most basic of questions about prevalence in population have not been available and remain unavailable. -

Pandemic.Pdf.Pdf

1 PANDEMICS: Past, Present, Future Published in 2021 by the Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Education for Peace and Challenges & Opportunities Sustainable Development, 35 Ferozshah Road, New Delhi 110001, India © UNESCO MGIEP This publication is available in Open Access under the Attribution-ShareAlike Coordinating Lead Authors: 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ ANANTHA KUMAR DURAIAPPAH by-sa/3.0/ igo/). By using the content of this publication, the users accept to be Director, UNESCO MGIEP bound by the terms of use of the UNESCO Open Access Repository (http:// www.unesco.org/openaccess/terms-use-ccbysa-en). KRITI SINGH Research Officer, UNESCO MGIEP The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they Lead Authors: NANDINI CHATTERJEE SINGH are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. Senior Programme Officer, UNESCO MGIEP The publication can be cited as: Duraiappah, A. K., Singh, K., Mochizuki, Y. YOKO MOCHIZUKI (Eds.) (2021). Pandemics: Past, Present and Future Challenges and Opportunities. Head of Policy, UNESCO MGIEP New Delhi. UNESCO MGIEP. SHAHID JAMEEL Coordinating Lead Authors: Director, Trivedi School of Biosciences, Ashoka University Anantha Kumar Duraiappah, Director, UNESCO MGIEP Kriti Singh, Research Officer, UNESCO MGIEP Lead Authors: Nandini Chatterjee Singh, Senior Programme Officer, UNESCO MGIEP Contributing Authors: CHARLES PERRINGS Yoko Mochizuki, Head of Policy, UNESCO MGIEP Global Institute of Sustainability, Arizona State University Shahid Jameel, Director, Trivedi School of Biosciences, Ashoka University W. -

WHO COVID-19 Database Search Strategy (Updated 26 May 2021)

Search purpose: Systematic search of the COVID-19 literature performed Monday through Friday for the WHO Database. Search strategy as of 26 May 2021. Searches performed by Tomas Allen, Kavita Kothari, and Martha Knuth. Use following commands to pull daily new entries: Entry_date:( [20210101 TO 20210120]) Entry_date:( 20210105) Duplicates: Duplicates are found in EndNote and Distillr using the Wichor method. Further screening is done by expert reviewers but some duplicates may still be in the database. Daily Search Strategy: Database Daily Search Strategy Medline (coronavir* OR corona virus* OR corona pandemic* OR betacoronavir* OR covid19 OR covid OR (Ovid) nCoV OR novel CoV OR CoV 2 OR CoV2 OR sarscov2 OR sars2 OR 2019nCoV OR wuhan virus* OR 1946- NCOV19 OR solidarity trial OR operation warp speed OR COVAX OR "ACT-Accelerator" OR BNT162b2 OR comirnaty OR "mRNA-1273" OR CoviShield OR AZD1222 OR Sputnik V OR CoronaVac OR "BBIBP-CorV" OR "Ad26.CoV2.S" OR "JNJ-78436735" OR Ad26COVS1 OR VAC31518 OR EpiVacCorona OR Convidicea OR "Ad5-nCoV" OR Covaxin OR CoviVac OR ZF2001 OR "NVX-CoV2373" OR "ZyCoV-D" OR CIGB 66 OR CVnCoV OR "INO-4800" OR "VIR-7831" OR "UB-612" OR BNT162 OR Soberana 1 OR Soberana 2 OR "B.1.1.7" OR "VOC 202012/01" OR "VOC202012/01" OR "VUI 202012/01" OR "VUI202012/01" OR "501Y.V1" OR UK Variant OR Kent Variant OR "VOC 202102/02" OR "VOC202102/02" OR "B.1.351" OR "VOC 202012/02" OR "VOC202012/02" OR "20H/501.V2" OR "20H/501Y.V2" OR "501Y.V2" OR "501.V2" OR South African Variant OR "B.1.1.28.1" OR "B.1.1.28" OR "B.1.1.248" OR -

City Space and Urban Identity a Post-9/11 Consciousness in Australian Fiction 2005 to 2011

City Space and Urban Identity A Post-9/11 Consciousness in Australian Fiction 2005 to 2011 By Lydia Saleh Rofail A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English. Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney 2019 Declaration of Originality I affirm that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and I certify and warrant to the best of my knowledge that all sources of reference have been duly and fully acknowledged. Lydia Saleh Rofail i Abstract This thesis undertakes a detailed examination of a close corpus of five Australian literary novels published between 2005 and 2011, to assess the political, social, and cultural implications of 9/11 upon an urban Australian identity. My analysis of the literary city will reveal how this identity is trapped between layers of trauma which include haunting historical atrocities and inward nationalism, as well as the contrasting outward pull of global aspirations. Dead Europe by Christos Tsiolkas (2005), The Unknown Terrorist by Richard Flanagan (2006), Underground by Andrew McGahan (2006), Breath by Tim Winton (2008), and Five Bells by Gail Jones (2011) are uniquely varied narratives written in the shadow of 9/11. These novels reconfigure fictional notions of Australian urbanism in order to deal with fears and threats posed by 9/11 and the fallout that followed, where global interests fed into national concerns and discourses within Australia and resonated down to local levels. Adopting an Australia perspective, this thesis contextualises subsequent traumatic and apocalyptic trajectories in relation to urbanism and Australian identity in a post-9/11 world. -

National Covid-19 Coordination Commission (Nccc)

25th May 2020 Senator Katy Gallagher, Chair Select Committee on COVID-19 ℅ Committee Secretary Dear Senator Gallagher and Members of the Select Committee on Covid-19, I am writing to the Select Committee on COVID-19 as an Australian citizen. I have focussed my submission on my concerns regarding potential financial conflicts of interest in the Australian Government’s Covid-19 advisors. Please note that this submission contains excerpts from an extensive report I have published, entitled ‘Covid-19: Plandemic Profit.Fallout1.’ NATIONAL COVID-19 COORDINATION COMMISSION (NCCC) EXECUTIVE BOARD In March 2020, Prime Minister Scott Morrison announced the creation of the ‘National Covid-19 Coordination Commission (NCCC). “An Executive Board of Commissioners, will advise the Prime Minister on all non-health aspects of the pandemic response… [the Board will] coordinate advice to the Australian Government on actions to anticipate and mitigate the economic and social effects of the global coronavirus pandemic…. This is about working cooperatively across private-to-private and public-to-private networks to unlock resources…”2 Upon examination, the Board Members of the NCCC do not appear to represent the interests of small business or ‘everyday Australians’. Instead, they hold senior board positions of companies in mining, oil and gas, airlines, private hospitals, pharmaceutical companies, casinos and superannuation giants. One member is a billionaire. Another was recently accused for being ‘an international tax dodger’ by an Australian Senator. Another Chairs an international organisation at the forefront of brokering private-public partnerships and garnering billions in taxpayer dollars to fund Covid-19 vaccine development. The Morrison Government’s choice of NCCC board members, and the glaring omission of any member who could be said to represent small business or employee unions, is a farcical premise of ‘mitigating the economic and social effects’ of Covid-10. -

Creating the Fastest Economic Recovery

x Chapter 1 Creating the Fastest Economic Recovery The beginning of 2020 ushered in a strong U.S. economy that was delivering job, income, and wealth gains to Americans of all backgrounds. By February 2020, the unemployment rate had fallen to 3.5 percent—the lowest in 50 years— and unemployment rates for minority groups and historically disadvantaged Americans were at or near their lowest points in recorded history. Wages were rising faster for workers than for managers, income and wealth inequality were on the decline, and median incomes for minority households were experienc- ing especially rapid gains. The fruits of this strong labor market expansion from 2017 to 2019 also included lifting 6.6 million people out of poverty, which is the largest three-year drop to start any presidency since the War on Poverty began in 1964. These accomplishments highlight the success of the Trump Administration’s pro-growth, pro-worker policies. The robust state of the U.S. economy in the three years through 2019 led almost all forecasters to expect continued healthy growth through 2020 and beyond. However, in late 2019 and the early months of 2020, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19, with origins in the People’s Republic of China, began spreading around the globe and eventually within the United States, causing a pandemic and bringing with it an unprecedented economic and public health crisis. Both the demand and supply sides of the economy suffered sudden and massive shocks due to the pandemic. During the springtime lockdowns aimed at “flattening the curve,” the labor market lost 22.2 million jobs, and the unemployment rate jumped 11.2 percentage points, to 14.7 percent—the largest monthly changes in the series’ histories. -

COVID-19 & the Swedish Conundrum: Part I Why Did Sweden Not Lock

COVID-19 & The Swedish Conundrum: Part I Why did Sweden not lock down? What were they trying to achieve? Prathap Tharyan The world is cautiously trying to emerge from lockdowns People enjoying the sun in Stockholm on April 21, 2020 Jonathan Nackstrand /AFP via Getty images (Business Insider May 4 2020) No Lockdown: Do the Swedes know something the rest of the world does not know? Or are they playing “Russian Roulette” with their “Herd Immunity” strategy? SWEDEN’S RELAXED CORONAVIRUS RESPONSE NO LOCKDOWN IN SWEDEN: A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT IN COMBATING COVID-19 Cafes, bars, restaurants, elementary schools and most businesses, including hair salons and gyms are open and people are allowed to exercise outdoors Parks and public spaces are open Pubs and bars remain open https://edition.cnn.com/2020/04/28/europe/sweden- Photograph: Ali Lorestani/EPA (The Guardian March 23) coronavirus-lockdown-strategy-intl/index.html WHY IS SWEDEN IS ‘DOING NOTHING’? Advice from the Public Health Agency Sweden has recommended good hygiene as part of infection control “Face masks are meant for Sweden’s Public Health Agency healthcare staff and not needed in in does not recommend face masks the community. for the public The best way to protect oneself and others in daily life is to maintain social distancing and good hand hygiene” SWEDISH PUBLIC HEALTH AGENCY RECOMMENDS SOCIAL DISTANCING No large gatherings (50 people max.) Does not apply to schools, public transport, gyms Work from home if possible Keep arms-length distance from others in all public spaces including -

Frequently Asked Questions About the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Impact on Funding Arrangements

Frequently asked questions about the Coronavirus (COVID-19) impact on funding arrangements The following questions and answers have been developed by the Department of Social Services (the department) to assist funded service providers (and prospective organisations) in service delivery arrangements in light of the Coronavirus (COVID-19). There will be evolving information and guidance provided by government and we encourage you seek up to date information. Please contact your Funding Arrangement Manager in the first instance to discuss your individual circumstances and to find a flexible solution. You can contact them using the emails below: State / Territory Email address Queensland [email protected] New South Wales [email protected] Australian Capital Territory [email protected] Victoria [email protected] Tasmania [email protected] South Australia [email protected] Western Australia [email protected] Northern Territory [email protected] If you are unable to contact your Funding Arrangement Manager, please contact the Community Grants Hotline via telephone 1800 020 283 (option 6), or TTY 1800 555 677. Questions and Answers General questions ........................................................................................................................ 2 Funding arrangements already in place ...................................................................................... -

Pharmaus20 Digital Forum Summary Report Medicines Australia About Pharmaus20

PharmAus20 Digital Forum Summary Report Medicines Australia About PharmAus20 PharmAus20 is Medicines Australia’s fourth annual Policy Symposium. Every year the Symposium provides a platform for an open discussion between industry experts and policymakers, with the goal of improving the future of healthcare in Australia. Usually held over one action packed day in Canberra, this year’s Symposium was held virtually over four sessions. The discussions focused on the lessons from COVID-19 and what they will mean for the future of innovation in the health and pharmaceuticals sector. PharmAus20 explored the impacts of COVID-19 on industry, patients, communities, and governments. The key presentations explored the COVID-19 lessons from international leaders on industry and government collaboration; how we can improve Australia’s whole of ecosystem approach to Research and Development; what COVID means for the long term trajectory of digital within the industry; and how the industry can help Australia recover from the economic impacts of the pandemic. The Symposium flagged what COVID-19 induced changes have meant for patients, and how the industry can ensure Australia is better prepared for the next crisis and the next stage of recovery. Over the course of the four weeks, 23 speakers, including the Federal Minister for Health, the Shadow Minister for Health and various stakeholders from the health sector offered their perspectives on what COVID-19 has meant for the medicines industry. The key ideas and themes that emerged from speakers and discussions at PharmAus20 are summarised in the pages below. 2 Key themes Heading 1 2 It takes the whole The industry has ecosystem to bring responded well to innovative COVID-19, but the treatments to journey is not over patients 3 4 Industry Consumers are reform plays a demanding the key role in ensuring industry integrates Australia’s economy digital offerings fares better than others 3 Overview Medicines Australia hosted PharmAus20 over four economy. -

The COVID-19-Crisis and the Information Polity: an Overview of Responses and Discussions in Twenty-One Countries from Six Continents

Information Polity 25 (2020) 243–274 243 DOI 10.3233/IP-200006 IOS Press Global Expert Report The COVID-19-crisis and the information polity: An overview of responses and discussions in twenty-one countries from six continents Albert Meijera and C. William R. Websterb aUtrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands bUniversity of Stirling, Scotland, UK Contributing Authors Frank Bannister, Colin J. Bennett, Kaiping Chen, Heungsuk Choi, J. Ignacio Criado, Maria Alexandra Cunha, Mehmet Akif Demircioglu, Mila Gasco-Hernandez, Paul Henman, Douglas Kimemia, Veiko Lember, Karl Löfgren, Luis F. Luna-Reyes, Albert Meijer, Ines Mergel, David Murakami Wood, Giorgia Nesti, Erico Przeybilovicz, Aarthi Raghavan, Ola Svenonius, Rosamunde van Brakel, William Webster, Mete Yildiz. Abstract. Governments around the world are utilizing data and information systems to manage the COVID-19-crisis. To obtain an overview of all these efforts, this global report presents the expert reports of 21 countries regarding the relation between the COVID-19-crisis and the information polity. A comparative analysis of these reports highlights that governments focus on strengthening six functions: management of information for crisis management, publishing public information for citizens, providing digital services to citizens, monitoring citizens in public space, facilitating information exchange between citizens and developing innovative responses to COVID-19. The comparative overview of information responses to the COVID-19-crisis shows that these responses cannot only be studied from a rational perspective on government information strategies but need to be studied as political and symbolic interventions. Keywords: COVID-19, information polity, corona app, corona dashboard 1. Introduction The COVID-19 Pandemic has diffused globally at an alarming rate and has forced countries to undertake a broad range of unprecedented interventions in order to protect their citizens from this disease. -

The Economics of a Pandemic: the Case of Covid-19

The economics of a pandemic: the case of Covid-19 Paolo Surico and Andrea Galeotti Professors of Economics at London Business School london.edu Financial support from the European Research Council and the Wheeler Institute is gratefully acknowledged. This Lecture 1. Science 2. Health policies 3. Economics 4. Macroeconomic policies london.edu The economics of a pandemic: The case of Covid-19 2 The enemy Source: The Economist, 14th March 2020 london.edu The economics of a pandemic: The case of Covid-19 3 The basics about Covid-19: what it is • The cause: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) • The disease: Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) • Possible origin in wet animal market in Wuhan, China, early Dec 2019 • A strain of the same virus as SARS-CoV-1, which affected 8,000 people in 2002/03 • 96% DNA match between bat coronavirus and human found in a study from February; suggests link to humans is not direct but through intermediate host • Initially pangolins were suspected, but now seems to not be so; still unclear • Made of 4 proteins and a strand of RNA (molecule which can store genetic information) • One protein is the spike, which gives the crown-like appearance • Two proteins sit in the membrane between the spikes to provide structural integrity • In the membrane, the fourth protein is a scaffold around the genetic material Source: The Economist, 23rd January 2020; Nature: “Mystery deepens over animal source of coronavirus” https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-00548-w london.edu The economics of a pandemic: The case of Covid-19 4 The basics about Covid-19: how it works • Enters through nose, mouth, or eyes.