Weaving, Death-Weaving, Fate-Weaving, Creation- and Water-Weaving, Word-Weaving, and Spider-Weaving

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

King's Research Portal

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1017/S0263675100080327 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Naismith, R. G. R. (2017). The Ely Memoranda and the Economy of the Late Anglo-Saxon Fenland. Anglo- Saxon England , 45, 333-377. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0263675100080327 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Index of Heads

Cambridge University Press 0521804523 - The Heads of Religious Houses: England and Wales, 940-1216 - Second Edition Edited by David Knowles, C. N. L. Brooke and Vera C. M. London Index More information INDEX OF HEADS This index is solely a list of heads, the information being kept to a minimum for convenience in use. The order is based on Christian names, with abbots before priors, abbesses before prioresses, and in alphabetical order of their houses: surnames are always in parentheses and ignored in the order. The arrangement means that heads who moved from house to house occur twice: thus Adam, pr. Bermondsey, later abb. Evesham, appears under each, but with a cross-reference. Square brackets enclosing the name of a house indicate that the head moved to it later than and his name is not, therefore, to be found in the list for that house. Names occurring in earlier printed lists which we have eliminated are in italics; names due to scribal error are in inverted commas (with cross-reference to the correct form); and names queried in the lists are queried here. A., abb. Basingwerk, Adam, abb. Blanchland, A., abb. Chatteris, Adam, abb. Chertsey, A. (de Rouen), abb. Chatteris, , Adam, abb. Cirencester (pr. Bradenstoke), A., abb. Easby, , A., ‘abb.’ Hastings, Adam (de Campes), abb. Colchester, , A., abb. Milton, Adam, abb. Croxton Kerrial, A., pr. Canons Ashby, Adam, abb. Evesham (pr. Bermondsey), , A., pr. Car’, A., pr. Cockerham, Adam, abb. Eynsham, , A., pr. Hastings, Adam, abb. Garendon [abb. Waverley], A., pr. Monks Kirby, Adam (of Kendal), abb. Holm Cultram, A., pr. -

The Vengeance of Heaven and Earth in Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norman Society, C

Durham E-Theses 'Vengeance is mine': The Vengeance of Heaven and Earth in Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norman Society, c. 900 - c. 1150 STEED, ABIGAIL,FRANCES,GEORGINA How to cite: STEED, ABIGAIL,FRANCES,GEORGINA (2019) 'Vengeance is mine': The Vengeance of Heaven and Earth in Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norman Society, c. 900 - c. 1150 , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13072/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 ‘VENGEANCE IS MINE’: THE VENGEANCE OF HEAVEN AND EARTH IN ANGLO-SAXON AND ANGLO-NORMAN SOCIETY, C. 900 – C. 1150 Abigail Steed Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History, Durham University December 2018 1 Abigail Steed ‘Vengeance is mine’: The Vengeance of Heaven and Earth in Anglo-Saxon and Anglo- Norman Society, c. -

Introduction.Pdf

INTRODUCTION The Vita Wulfstani is here printed in full for the first time. In the first edition, that of Henry Wharton, published in 1692, about two- fifths of the Life were omitted.1 Most of the portions suppressed are accounts of miracles which contain some valuable information, but a number of other passages were left out without notice to the reader. Wharton's text was reprinted by Mabillon 2 and Migne,3 but no attempt has been made hitherto to examine the Life with the care required to show its relation to other historical literature of the period. The plan of this edition is to print first the full text of the Vita as preserved in MS. Cott. Claud. A.v. in the British Museum * 1 Anglia Sacra, II, pp. 239 seq. 'Ada Ord. Bened., Saec. VI, ii., p. 836. 3 Patrologia Latina, Vol. 179, p. 1734. 4 MS. Cott. Claud. A.v. is a small volume, 9! in. by 6| in., originally somewhat larger than at present, and seems to comprise three books which once existed separately. The first two are a fourteenth-century Peterborough Chronicle and a twelfth-century copy of William of Malmesbury's Gesta Pontificum, per- haps the best.extant MS. of the first recension. The former is certainly and the latter probably from the Library of Peterborough Abbey. The proven- ance of the third—fo. 135 to the end—is unknown. It is an early collection of saints' lives containing the Life of St. Erkenwald, Bishop of London, the Life and Miracles of St. Wenfred, the Life of St. -

Archbishop Wulfstan, Anglo-Saxon Kings, and the Problems of His Present." (2015)

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository English Language and Literature ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 9-1-2015 Rulers and the Wolf: Archbishop Wulfstan, Anglo- Saxon Kings, and the Problems of His Present Nicholas Schwartz Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/engl_etds Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Schwartz, Nicholas. "Rulers and the Wolf: Archbishop Wulfstan, Anglo-Saxon Kings, and the Problems of His Present." (2015). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/engl_etds/35 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Language and Literature ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Nicholas P. Schwartz Candidate English Language and Literature Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Dr. Jonathan Davis-Secord, Chairperson Dr. Helen Damico Dr. Timothy Graham Dr. Anita Obermeier ii RULERS AND THE WOLF: ARCHBISHOP WULFSTAN, ANGLO-SAXON KINGS, AND THE PROBLEMS OF HIS PRESENT by NICHOLAS P. SCHWARTZ BA, Canisius College, 2008 MA, University of Toledo, 2010 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico July, 2015 iii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my parents, Sharon and Peter Schwartz iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I have incurred many debts while writing this dissertation. First, I would like to thank my committee, Drs. -

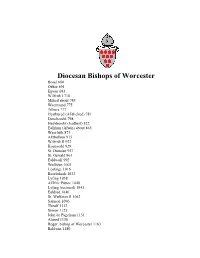

Diocesan Bishops of Worcester

Diocesan Bishops of Worcester Bosel 680 Oftfor 691 Egwin 693 Wilfrith I 718 Milred about 743 Waermund 775 Tilhere 777 Heathured (AEthelred) 781 Denebeorht 798 Heahbeorht (Eadbert) 822 Ealhhun (Alwin) about 845 Waerfrith 873 AEthelhun 915 Wilfrith II 922 Koenwald 929 St. Dunstan 957 St. Oswald 961 Ealdwulf 992 Wulfstan 1003 Leofsige 1016 Beorhtheah 1033 Lyfing 1038 AElfric Puttoc 1040 Lyfing (restored) 1041 Ealdred 1046 St. Wulfstan II 1062 Samson 1096 Theulf 1113 Simon 1125 John de Pageham 1151 Alured 1158 Roger, bishop of Worcester 1163 Baldwin 1180 William de Narhale 1185 Robert Fitz-Ralph 1191 Henry de Soilli 1193 John de Constantiis 1195 Mauger of Worcester 1198 Walter de Grey 1214 Silvester de Evesham 1216 William de Blois 1218 Walter de Cantilupe 1237 Nicholas of Ely 1266 Godfrey de Giffard 1268 William de Gainsborough 1301 Walter Reynolds 1307 Walter de Maydenston 1313 Thomas Cobham 1317 Adam de Orlton 1327 Simon de Montecute 1333 Thomas Hemenhale 1337 Wolstan de Braunsford 1339 John de Thoresby 1349 Reginald Brian 1352 John Barnet 1362 William Wittlesey 1363 William Lynn 1368 Henry Wakefield 1375 Tideman de Winchcomb 1394 Richard Clifford 1401 Thomas Peverell 1407 Philip Morgan 1419 Thomas Poulton 1425 Thomas Bourchier 1434 John Carpenter 1443 John Alcock 1476-1486 Robert Morton 1486-1497 Giovanni De Gigli 1497-1498 Silvestro De Gigli 1498-1521 Geronimo De Ghinucci 1523-1533 Hugh Latimer resigned title 1535-1539 John Bell 1539-1543 Nicholas Heath 1543-1551 John Hooper deprived of title 1552-1554 Nicholas Heath restored to title -

Eadric Streona :: a Critical Biography/ Terry Lee Locy University of Massachusetts Amherst

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1998 Eadric Streona :: a critical biography/ Terry Lee Locy University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Locy, Terry Lee, "Eadric Streona :: a critical biography/" (1998). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 1729. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/1729 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 31S0t)t)DlS7n5MS EADRIC STREONA: A CRITICAL BIOGRAPHY A Thesis Presented by TERRY LEE LOCY Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS September 1998 Department of History EADRIC STREONA: A CRITICAL BIOGRAPHY A Thesis Presented by TERRY LEE LOCY Approved as to style and content by: R. Dean Ware, Chairman i Mary Wicl^wire, Member Jack Imager, Ivlember Mary Wilson, Department Head Department of History TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Chapter I. EADRIC STREONA: AN INTRODUCTION 1 II. EALDORMAN EADRIC, CIRCA 975-1016 4 His Origins and Social Position in Anglo-Saxon England 4 Eadric's Rise to Power 13 Mercenarism and Murder in the era of yEthelred II 21 Eadric the Acquisitor 29 Eadric and Wales 33 The Danish War of 1013-1016 39 The Sensibilities of 1 0 1 6 50 III. EARL EADRIC, 1016-1017 53 Eadric's Position in late 1016 53 Eadric in Normandy 56 The Royal Succession 62 Queen Emma 66 The Royal Transition of 1017 73 The Vengeance of Canute 77 IV. -

Index of Moneyers Represented in the Catalogue

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-26016-9 — Medieval European Coinage Edited by Rory Naismith Index More Information INDEX OF MONEYERS REPRESENTED IN THE CATALOGUE Ordinary type indicates pages, bold type catalogue entries. Abba (Chester) 1474 , (Mercia) 1300 Ælfwine (Bristol) 1984 , (Cambridge) 1820 , (Chester) Abenel 2355 , 2456 , 2487 1479 , (Chichester) 2291 , 2322 , (Cricklade) 2110 , Aculf (east midlands) 1667 (Huntingdon) 2138 , (London) 1937 , 1966 , 2140 , Adalaver (east midlands) 1668 – 9 (Maldon) 1855 – 6 , (Thetford) 2268 , (Wilton) 2125 , 2160 , Adalbert 2457 – 9 , (east midlands) 1305 – 6 2179 Ade (Cambridge) 1947 , 1986 Æscman (east midlands) 1606 , 1670 , (Stamford) 1766 Adma (Cambridge) 1987 Æscwulf (York) 1697 Adrad 2460 Æthe… (London) 1125 Æ… (Chester) 1996 Æthel… (Winchester) 1922 Ælf erth 1511 , 1581 Æthelferth 1560 , (Bath) 1714 , (Canterbury) 1451 , (Norwich) Ælfgar (London) 1842 2051 , (York) 1487 , 2605 ; 303 Ælfgeat (London) 1843 Æthelgar 1643 , (Winchester) 1921 Ælfheah (Stamford) 2103 Æthelhelm (East Anglia) 940 , (Northumbria) 833 , 880 – 6 Ælfhere (Canterbury) 1228 – 9 Æthelhere (Rochester) 1215 Ælfhun (London) 1069 Æthellaf (London) 1126 , 1449 , 1460 Ælfmær (Oxford) 1913 Æthelmær (Lincoln) 2003 Ælfnoth (London) 1755 , 1809 , 1844 Æthelmod (Canterbury) 955 Ælfræd (east midlands) 1556 , 1660 , (London) 2119 , (Mercia/ Æthelnoth 1561 – 2 , (Canterbury) 1211 , (east midlands) 1445 , Wessex) 1416 , ( niweport ) (Lincoln) 1898 , 1962 Ælfric (Barnstaple) 2206 , (Cambridge) 1816 – 19 , 1875 – 7 , Æthelræd 90 -

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: Authorship and Origins

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: Authorship and Origins Part C. Chronicling at Canterbury before and after the Conquest S. R. Jensen This paper looks at the correlations between MSS C, D and E of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle over the course of the eleventh century. It first argues that MSS C, and '√D' and '√E' (the antecessors of D and E, respectively), all begin their lives at Canterbury in the 1040s, with C being allocated to Siward, suffragan bishop at St Martin's; √E earmarked for Wulfric, bishop of St Augustine's; and √D ultimately assigned to the keeping of Ealdred, bishop of Worcester. It then suggests that √D is taken to York as Ealdred's personal copy, kept up there until the archbishop's death in late 1070, removed to Durham just before the attacks on the City, continued at Durham to 1084, and subsequently brought back to Canterbury by 1085, where it is used in the revision of C and of √E, as well as in the making of D. It stresses that D is not in any way a contemporary text; proposes that there is no significant link between C and Abingdon; and suggests that there is scant evidence for an early northern recension of the Chronicle. The analysis relies largely on comparisons between the blocks of composition and the stretches of handwriting in the different texts. Copyright© S. R. Jensen, 2016 Printed and published by: ARRC Publishing, P. O. Box 886, Narrabeen. NSW. 2101. Australia ISBN: 978-0-9875081-0-2 This work is currently available only in electronic form, although the series in all its parts will eventually be presented in hard copy. -

A Critical Study of the Works of Wulfstan, Archbishop of York (1002-1023)

A Critical Study of the Works of Wulfstan Archbishop of York (1002-1023) Richard Douglas Monaghan BA, Loyola College, l'universite/ de ~ontrgal,1968 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English @ Richard Douglas Monaghan 1970 Simon Fraser University August, 1970 Approval Name: Richard Douglas Monaghan Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: Critical Study of the Works of Wulfstan Archbishop of York (1002-1023) Examining Committee: Joseph GallagHer Senior Supervisor James Sandison Examining Committee John Mills Examining Committee Date Approved: ~ugust5, 1970 iii Abstract of Thesis The title of the thesis is: A Critical Study of the Works of Wulfstan Archbishop of York (1002-1023). The thesis itself is centred around a conception of literature and literary art as ideology, which leads to the conclusion that the primary concern of a literary artist is social relations; or political theory is the core of literature. The paper begins by examining the political situation of the north of England at the close of the tenth century. The two major movements are the Scandanavian expansion and the institution of the Benedictine Reform. The second chapter establishes the relationship of Wulfstan to the struggle for a catholic hegemony over the whole of Europe, but particularly Danish England, Chapter three is an item by item analysis of the works attributed to Wulfstan by scholars, works which I also consider to be his, There is next to no analysis of texts which have been attributed to him which I do not consider to be genuine, There are sixty-eight items under consideration: forty homilies, twenty institutional pieces (including laws, canons, and institutes), a short liturgical item, and incidental letters, charters and poems, Grounds for ascription are stylistic, linguistic, and the commonality or sources, The final chapter analyzes the policy of the Canon, and iv the implications of the conclusions reached takes us back to the statement of the thesis. -

The Anti-Monastic Reaction in the Reigns of Edward the Martyr and Æthelred Ii, 975-993: a Time of Opportunism

DOĞUŞ AYTAÇ DOĞUŞ THE ANTI-MONASTIC REACTION IN THE REIGNS OF EDWARD THE MARTYR AND ÆTHELRED II, 975-993: A TIME OF OPPORTUNISM A Master’s Thesis THE ANTI THE MARTYR by - DOĞUŞ AYTAÇ MONASTIC REACTION IN THE REIGNS OF EDWARD OF REACTION REIGNS THE MONASTIC THE IN AND ÆTHELRED II, 975 ÆTHELRED AND II, - 993: A TIME OPPORTUNISM993:OF A TIME Department of History Bilkent 2020 University İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University Ankara August 2020 To my family THE ANTI-MONASTIC REACTION IN THE REIGNS OF EDWARD THE MARTYR AND ÆTHELRED II, 975-993: A TIME OF OPPORTUNISM The Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences of İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University by DOĞUŞ AYTAÇ In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY İHSAN DOĞRAMACI BİLKENT UNİVERSITY ANKARA AUGUST 2020 ABSTRACT THE ANTI-MONASTIC REACTION IN THE REIGNS OF EDWARD THE MARTYR AND ÆTHELRED II, 975-993: A TIME OF OPPORTUNISM Aytaç, Doğuş M.A, Department of History Supervisor: Assist. Prof. Dr. David E. Thornton August 2020 This thesis aims to provide a new insight into the so-called anti-monastic reaction which took place after King Edgar’s death in 975 by analysing all the available evidence from fourteen different monasteries and bishoprics known to be affected during this period. It has been usually thought that the anti-monastic reaction was mainly caused by the politics of the period, but the present study argues that the reaction was an act of opportunism. The actions of small landowners and the great landowners are considered according to their contexts: both acted out of opportunism, but the latter’s actions were also related to their personal bonds and interests. -

UNIVERSITY of WINCHESTER Viking 'Otherness' in Anglo-Norman Chronicles Paul Victor Store ORCID: 0000-0003-4626-4143 Doctor

UNIVERSITY OF WINCHESTER Viking ‘otherness’ in Anglo-Norman chronicles Paul Victor Store ORCID: 0000-0003-4626-4143 Doctor of Philosophy June 2018 This Thesis has been completed as a requirement for a postgraduate research degree of the University of Winchester. Declaration and Copyright Statements First Declaration No portion of the work referred to in the Thesis has been submitted in support of an application for another degree or qualification of this or any other university or other institute of learning. Second Declaration I confirm that this Thesis is entirely my own work. Copyright © Paul Victor Store, 2018, Viking ‘otherness’ in Anglo-Norman chronicles, University of Winchester, PhD Thesis, Page range pp 1 - 221, ORCID 0000-0003-4626-4143. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. Copies (by any process) either in full, or of extracts, may be made only in accordance with instructions given by the author. Details may be obtained from the RKE Centre, University of Winchester. This page must form part of any such copies made. Further copies (by any process) of copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the permission (in writing) of the author. No profit may be made from selling, copying or licensing the author’s work without further agreement. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from this source may be published without proper acknowledgement. 1 Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my Director of Studies, Ryan Lavelle, for his continuous support of my study, for his encouragement, challenges, and knowledge.