King Edgar's Charter for Pershore (AD 972)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kent Academic Repository Full Text Document (Pdf)

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Gallagher, Robert and TINTI, FRANCESCA (2018) Latin, Old English and documentary practice at Worcester from Wærferth to Oswald. Anglo-Saxon England . ISSN 0263-6751. (In press) DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/72334/ Document Version Author's Accepted Manuscript Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Latin, Old English and documentary practice at Worcester from Wærferth to Oswald ROBERT GALLAGHER AND FRANCESCA TINTI ABSTRACT This article analyses the uses of Latin and Old English in the charters of Worcester cathedral, which represents one of the largest and most linguistically interesting of the surviving Anglo-Saxon archives. Specifically focused on the period encompassing the episcopates of Wærferth and Oswald (c. 870 to 992), this survey examines a time of intense administrative activity at Worcester, contemporaneous with significant transformations in the political and cultural life of Anglo-Saxon England more generally. -

Colleague, Critic, and Sometime Counselor to Thomas Becket

JOHN OF SALISBURY: COLLEAGUE, CRITIC, AND SOMETIME COUNSELOR TO THOMAS BECKET By L. Susan Carter A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of History–Doctor of Philosophy 2021 ABSTRACT JOHN OF SALISBURY: COLLEAGUE, CRITIC, AND SOMETIME COUNSELOR TO THOMAS BECKET By L. Susan Carter John of Salisbury was one of the best educated men in the mid-twelfth century. The beneficiary of twelve years of study in Paris under the tutelage of Peter Abelard and other scholars, John flourished alongside Thomas Becket in the Canterbury curia of Archbishop Theobald. There, his skills as a writer were of great value. Having lived through the Anarchy of King Stephen, he was a fierce advocate for the liberty of the English Church. Not surprisingly, John became caught up in the controversy between King Henry II and Thomas Becket, Henry’s former chancellor and successor to Theobald as archbishop of Canterbury. Prior to their shared time in exile, from 1164-1170, John had written three treatises with concern for royal court follies, royal pressures on the Church, and the danger of tyrants at the core of the Entheticus de dogmate philosophorum , the Metalogicon , and the Policraticus. John dedicated these works to Becket. The question emerges: how effective was John through dedicated treatises and his letters to Becket in guiding Becket’s attitudes and behavior regarding Church liberty? By means of contemporary communication theory an examination of John’s writings and letters directed to Becket creates a new vista on the relationship between John and Becket—and the impact of John on this martyred archbishop. -

Welsh Kings at Anglo-Saxon Royal Assemblies (928–55) Simon Keynes

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo Keynes The Henry Loyn Memorial Lecture for 2008 Welsh kings at Anglo-Saxon royal assemblies (928–55) Simon Keynes A volume containing the collected papers of Henry Loyn was published in 1992, five years after his retirement in 1987.1 A memoir of his academic career, written by Nicholas Brooks, was published by the British Academy in 2003.2 When reminded in this way of a contribution to Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norman studies sustained over a period of 50 years, and on learning at the same time of Henry’s outstanding service to the academic communities in Cardiff, London, and elsewhere, one can but stand back in awe. I was never taught by Henry, but encountered him at critical moments—first as the external examiner of my PhD thesis, in 1977, and then at conferences or meetings for twenty years thereafter. Henry was renowned not only for the authority and crystal clarity of his published works, but also as the kind of speaker who could always be relied upon to bring a semblance of order and direction to any proceedings—whether introducing a conference, setting out the issues in a way which made one feel that it all mattered, and that we stood together at the cutting edge of intellectual endeavour; or concluding a conference, artfully drawing together the scattered threads and making it appear as if we’d been following a plan, and might even have reached a conclusion. First place at a conference in the 1970s and 1980s was known as the ‘Henry Loyn slot’, and was normally occupied by Henry Loyn himself; but once, at the British Museum, he was for some reason not able to do it, and I was prevailed upon to do it in his place. -

King's Research Portal

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1017/S0263675100080327 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Naismith, R. G. R. (2017). The Ely Memoranda and the Economy of the Late Anglo-Saxon Fenland. Anglo- Saxon England , 45, 333-377. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0263675100080327 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

INDULGENCES and SOLIDARITY in LATE MEDIEVAL ENGLAND By

INDULGENCES AND SOLIDARITY IN LATE MEDIEVAL ENGLAND by ANN F. BRODEUR A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto Copyright by Ann F. Brodeur, 2015 Indulgences and Solidarity in Late Medieval England Ann F. Brodeur Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto 2015 Abstract Medieval indulgences have long had a troubled public image, grounded in centuries of confessional discord. Were they simply a crass form of medieval religious commercialism and a spiritual fraud, as the reforming archbishop Cranmer charged in his 1543 appeal to raise funds for Henry VIII’s contributions against the Turks? Or were they perceived and used in a different manner? In his influential work, Indulgences in Late Medieval England: Passports to Paradise, R.N. Swanson offered fresh arguments for the centrality and popularity of indulgences in the devotional landscape of medieval England, and thoroughly documented the doctrinal development and administrative apparatus that grew up around indulgences. How they functioned within the English social and devotional landscape, particularly at the local level, is the focus of this thesis. Through an investigation of published episcopal registers, my thesis explores the social impact of indulgences at the diocesan level by examining the context, aims, and social make up of the beneficiaries, as well as the spiritual and social expectations of the granting bishops. It first explores personal indulgences given to benefit individuals, specifically the deserving poor and ransomed captives, before examining indulgences ii given to local institutions, particularly hospitals and parishes. Throughout this study, I show that both lay people and bishops used indulgences to build, reinforce or maintain solidarity and social bonds between diverse groups. -

Index of Heads

Cambridge University Press 0521804523 - The Heads of Religious Houses: England and Wales, 940-1216 - Second Edition Edited by David Knowles, C. N. L. Brooke and Vera C. M. London Index More information INDEX OF HEADS This index is solely a list of heads, the information being kept to a minimum for convenience in use. The order is based on Christian names, with abbots before priors, abbesses before prioresses, and in alphabetical order of their houses: surnames are always in parentheses and ignored in the order. The arrangement means that heads who moved from house to house occur twice: thus Adam, pr. Bermondsey, later abb. Evesham, appears under each, but with a cross-reference. Square brackets enclosing the name of a house indicate that the head moved to it later than and his name is not, therefore, to be found in the list for that house. Names occurring in earlier printed lists which we have eliminated are in italics; names due to scribal error are in inverted commas (with cross-reference to the correct form); and names queried in the lists are queried here. A., abb. Basingwerk, Adam, abb. Blanchland, A., abb. Chatteris, Adam, abb. Chertsey, A. (de Rouen), abb. Chatteris, , Adam, abb. Cirencester (pr. Bradenstoke), A., abb. Easby, , A., ‘abb.’ Hastings, Adam (de Campes), abb. Colchester, , A., abb. Milton, Adam, abb. Croxton Kerrial, A., pr. Canons Ashby, Adam, abb. Evesham (pr. Bermondsey), , A., pr. Car’, A., pr. Cockerham, Adam, abb. Eynsham, , A., pr. Hastings, Adam, abb. Garendon [abb. Waverley], A., pr. Monks Kirby, Adam (of Kendal), abb. Holm Cultram, A., pr. -

The Vengeance of Heaven and Earth in Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norman Society, C

Durham E-Theses 'Vengeance is mine': The Vengeance of Heaven and Earth in Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norman Society, c. 900 - c. 1150 STEED, ABIGAIL,FRANCES,GEORGINA How to cite: STEED, ABIGAIL,FRANCES,GEORGINA (2019) 'Vengeance is mine': The Vengeance of Heaven and Earth in Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norman Society, c. 900 - c. 1150 , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13072/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 ‘VENGEANCE IS MINE’: THE VENGEANCE OF HEAVEN AND EARTH IN ANGLO-SAXON AND ANGLO-NORMAN SOCIETY, C. 900 – C. 1150 Abigail Steed Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History, Durham University December 2018 1 Abigail Steed ‘Vengeance is mine’: The Vengeance of Heaven and Earth in Anglo-Saxon and Anglo- Norman Society, c. -

Introduction.Pdf

INTRODUCTION The Vita Wulfstani is here printed in full for the first time. In the first edition, that of Henry Wharton, published in 1692, about two- fifths of the Life were omitted.1 Most of the portions suppressed are accounts of miracles which contain some valuable information, but a number of other passages were left out without notice to the reader. Wharton's text was reprinted by Mabillon 2 and Migne,3 but no attempt has been made hitherto to examine the Life with the care required to show its relation to other historical literature of the period. The plan of this edition is to print first the full text of the Vita as preserved in MS. Cott. Claud. A.v. in the British Museum * 1 Anglia Sacra, II, pp. 239 seq. 'Ada Ord. Bened., Saec. VI, ii., p. 836. 3 Patrologia Latina, Vol. 179, p. 1734. 4 MS. Cott. Claud. A.v. is a small volume, 9! in. by 6| in., originally somewhat larger than at present, and seems to comprise three books which once existed separately. The first two are a fourteenth-century Peterborough Chronicle and a twelfth-century copy of William of Malmesbury's Gesta Pontificum, per- haps the best.extant MS. of the first recension. The former is certainly and the latter probably from the Library of Peterborough Abbey. The proven- ance of the third—fo. 135 to the end—is unknown. It is an early collection of saints' lives containing the Life of St. Erkenwald, Bishop of London, the Life and Miracles of St. Wenfred, the Life of St. -

Künzel, Stefanie (2018) Concepts of Infectious, Contagious, And

Concepts of Infectious, Contagious, and Epidemic Disease in Anglo-Saxon England Stefanie Künzel, MA. Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy SEPTEMBER 2017 This page is intentionally left blank. Abstract This thesis examines concepts of disease existing in the Anglo-Saxon period. The focus is in particular on the conceptual intricacies pertaining to pestilence or, in modern terms, epidemic disease. The aim is to (1) establish the different aspects of the cognitive conceptualisation and their representation in the language and (2) to illustrate how they are placed in relation to other concepts within a broader understanding of the world. The scope of this study encompasses the entire corpus of Old English literature, select Latin material produced in Anglo-Saxon England, as well as prominent sources including works by Isidore of Seville, Gregory of Tours, and Pope Gregory the Great. An introductory survey of past scholarship identifies main tenets of research and addresses shortcomings in our understanding of historic depictions of epidemic disease, that is, a lack of appreciation for the dynamics of the human mind. The main body of research will discuss the topic on a lexico-semantic, contextual and wider cultural level. An electronic evaluation of the Dictionary of Old English Corpus establishes the most salient semantic fields surrounding instances of cwealm and wol (‘pestilence’), such as harmful entities, battle and warfare, sin, punishment, and atmospheric phenomena. Occurrences of pestilential disease are distributed across a variety of text types including (medical) charms, hagiographic and historiographic literature, homilies, and scientific, encyclopaedic treatises. The different contexts highlight several distinguishable aspects of disease, (‘reason’, ‘cause’, ‘symptoms’, ‘purpose’, and ‘treatment’) and strategically put them in relation with other concepts. -

Archbishop Wulfstan, Anglo-Saxon Kings, and the Problems of His Present." (2015)

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository English Language and Literature ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 9-1-2015 Rulers and the Wolf: Archbishop Wulfstan, Anglo- Saxon Kings, and the Problems of His Present Nicholas Schwartz Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/engl_etds Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Schwartz, Nicholas. "Rulers and the Wolf: Archbishop Wulfstan, Anglo-Saxon Kings, and the Problems of His Present." (2015). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/engl_etds/35 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Language and Literature ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Nicholas P. Schwartz Candidate English Language and Literature Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Dr. Jonathan Davis-Secord, Chairperson Dr. Helen Damico Dr. Timothy Graham Dr. Anita Obermeier ii RULERS AND THE WOLF: ARCHBISHOP WULFSTAN, ANGLO-SAXON KINGS, AND THE PROBLEMS OF HIS PRESENT by NICHOLAS P. SCHWARTZ BA, Canisius College, 2008 MA, University of Toledo, 2010 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico July, 2015 iii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my parents, Sharon and Peter Schwartz iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I have incurred many debts while writing this dissertation. First, I would like to thank my committee, Drs. -

"The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle" (Everyman Press, London, 1953, 1972)

"The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle " ****The Project Gutenberg Etext of The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle**** Translated by James Ingram Copyright laws are changing all over the world, be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before posting these files!! Please take a look at the important information in this header. We encourage you to keep this file on your own disk, keeping an electronic path open for the next readers. Do not remove this. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **Etexts Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *These Etexts Prepared By Hundreds of Volunteers and Donations* Information on contacting Project Gutenberg to get Etexts, and further information is included below. We need your donations. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Translated by James Ingram September, 1996 [Etext #657] ****The Project Gutenberg Etext of The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle**** *****This file should be named angsx10.txt or angsx10.zip****** Corrected EDITIONS of our etexts get a new NUMBER, angsx11.txt. VERSIONS based on separate sources get new LETTER, angsx10a.txt. We are now trying to release all our books one month in advance of the official release dates, for time for better editing. Please note: neither this list nor its contents are final till midnight of the last day of the month of any such announcement. The official release date of all Project Gutenberg Etexts is at Midnight, Central Time, of the last day of the stated month. A preliminary version may often be posted for suggestion, comment and editing by those who wish to do so. -

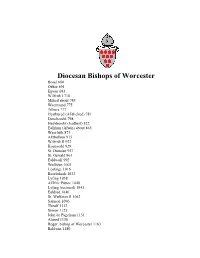

Diocesan Bishops of Worcester

Diocesan Bishops of Worcester Bosel 680 Oftfor 691 Egwin 693 Wilfrith I 718 Milred about 743 Waermund 775 Tilhere 777 Heathured (AEthelred) 781 Denebeorht 798 Heahbeorht (Eadbert) 822 Ealhhun (Alwin) about 845 Waerfrith 873 AEthelhun 915 Wilfrith II 922 Koenwald 929 St. Dunstan 957 St. Oswald 961 Ealdwulf 992 Wulfstan 1003 Leofsige 1016 Beorhtheah 1033 Lyfing 1038 AElfric Puttoc 1040 Lyfing (restored) 1041 Ealdred 1046 St. Wulfstan II 1062 Samson 1096 Theulf 1113 Simon 1125 John de Pageham 1151 Alured 1158 Roger, bishop of Worcester 1163 Baldwin 1180 William de Narhale 1185 Robert Fitz-Ralph 1191 Henry de Soilli 1193 John de Constantiis 1195 Mauger of Worcester 1198 Walter de Grey 1214 Silvester de Evesham 1216 William de Blois 1218 Walter de Cantilupe 1237 Nicholas of Ely 1266 Godfrey de Giffard 1268 William de Gainsborough 1301 Walter Reynolds 1307 Walter de Maydenston 1313 Thomas Cobham 1317 Adam de Orlton 1327 Simon de Montecute 1333 Thomas Hemenhale 1337 Wolstan de Braunsford 1339 John de Thoresby 1349 Reginald Brian 1352 John Barnet 1362 William Wittlesey 1363 William Lynn 1368 Henry Wakefield 1375 Tideman de Winchcomb 1394 Richard Clifford 1401 Thomas Peverell 1407 Philip Morgan 1419 Thomas Poulton 1425 Thomas Bourchier 1434 John Carpenter 1443 John Alcock 1476-1486 Robert Morton 1486-1497 Giovanni De Gigli 1497-1498 Silvestro De Gigli 1498-1521 Geronimo De Ghinucci 1523-1533 Hugh Latimer resigned title 1535-1539 John Bell 1539-1543 Nicholas Heath 1543-1551 John Hooper deprived of title 1552-1554 Nicholas Heath restored to title