Copyright Undertaking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SHAKESPEARE STUDIES in CHINA by Hui Meng Submitted to the Graduate Degree Program in English and the Graduate Faculty of the Un

SHAKESPEARE STUDIES IN CHINA By Copyright 2012 Hui Meng Submitted to the graduate degree program in English and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Geraldo U. de Sousa ________________________________ Misty Schieberle ________________________________ Jonathan Lamb Date Defended: April 3, 2012 ii The Thesis Committee for Hui Meng certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: SHAKESPEARE STUDIES IN CHINA ________________________________ Chairperson Geraldo U. de Sousa Date approved: April 3, 2012 iii Abstract: Different from Germany, Japan and India, China has its own unique relation with Shakespeare. Since Shakespeare’s works were first introduced into China in 1904, Shakespeare in China has witnessed several phases of developments. In each phase, the characteristic of Shakespeare studies in China is closely associated with the political and cultural situation of the time. This thesis chronicles and analyzes noteworthy scholarship of Shakespeare studies in China, especially since the 1990s, in terms of translation, literary criticism, and performances, and forecasts new territory for future studies of Shakespeare in China. iv Table of Contents Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………1 Section 1 Oriental and Localized Shakespeare: Translation of Shakespeare’s Plays in China …………………………………………………………………... 3 Section 2 Interpretation and Decoding: Contemporary Chinese Shakespeare Criticism………………………………………………………………. -

Foreigners Under Mao

Foreigners under Mao Western Lives in China, 1949–1976 Beverley Hooper Hong Kong University Press Th e University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © 2016 Hong Kong University Press ISBN 978-988-8208-74-6 (Hardback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any infor- mation storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Cover images (clockwise from top left ): Reuters’ Adam Kellett-Long with translator ‘Mr Tsiang’. Courtesy of Adam Kellett-Long. David and Isobel Crook at Nanhaishan. Courtesy of Crook family. George H. W. and Barbara Bush on the streets of Peking. George Bush Presidential Library and Museum. Th e author with her Peking University roommate, Wang Ping. In author’s collection. E very eff ort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. Th e author apologizes for any errors or omissions and would be grateful for notifi cation of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Paramount Printing Co., Ltd. in Hong Kong, China Contents Acknowledgements vii Note on transliteration viii List of abbreviations ix Chronology of Mao’s China x Introduction: Living under Mao 1 Part I ‘Foreign comrades’ 1. -

Stones from Other Hills: the Impact of Death of a Salesman on the Revival of Chinese Theatre in the 1980S

Stones From Other Hills: The Impact of Death of a Salesman on the Revival of Chinese Theatre in the 1980s The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:37736770 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Stones from Other Hills: The Impact of Death of a Salesman on the Revival of Chinese Theatre in the 1980s. Qiuyu Wang A Thesis in the Field of Dramatic Arts for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University November 2017 © 2017 Qiuyu Wang Abstract This study examines Arthur Miller’s involvement with a 1983 production of Death of a Salesman in Beijing. Through an analysis of primary and secondary sources, I evaluate this production in a broader historical context to give a more nuanced and complex account of how the production came to be. I piece together previous scholarship to provide a richer historical context for the play’s production. I identify the main reasons why Miller was asked to come to China, arguing that the ambiguous nature of the play served as a testing ground for Chinese artists to explore what artistic freedoms were extended to them in the years following the Cultural Revolution. The historical context of the years following the Cultural Revolution also influenced the play’s reception as audiences saw, beyond Miller’s theme of “one humanity,” an aspiration towards economic success and individualism. -

Chinese Literature

INESE ele12 LI. HRAT RE Iffi s( ffi ;.t'' -? CONTENTS Lao She and His "Teahouse" -Ying Ruoclteng t In Reply to Some Questions About "Te"ahouse" -Lao Sbe t2 Teahouse (a play in three acts) - Lao She t6 The Arc of Wu Guanzhong-Zbang AnThi 97 POEMS rilflest Poems !7'ritten During a Visit to Germany - Ai Qing IOl Three Poems - Hrang Yongyu r09 STORIES In Vino Veritas - Sun Yucban II' NOTE,S ON ART Some Chinese Caitoon Films - Yang Sbuxin rr8 INTROI}UCING A CLASSICAL PAINTING .Wen "The Connoisseut's Studio" by Zhengming-Tian Xia 12, CHEONICLE r27 PLATESI Paintings by \[u Guanzhong 96'sj Cartoon Films 722-r23 The Connoisseur's Studio -W'en Zbengming lz6-tz7 Subiect Index, Cbinese Literatarc 1979 Nos, r-rz rrl Front Cover: Autumn Song-Z.bu Junsban No. 12, 19?9 i t Ying Ruocheng Lao She and His "Teahouse', pieces and world classics. A glance at the entertainments columns The reasons for this are manifold. Lao She was honoured with the title of "People's Arrist" in r95r, the only author to receive such a designation in the history of the people,s Republic. Up to the time of his tragic death in ry66 he more than lived up to it. His literaty output after his return to Beijing from the United States in rg49 was prolific, by f.ar surpassing all the writers of the older Published by Foreign Languages Press Beiling (37), China Pri.nted in tbe People's Republic ol Cbina 1 I generation. Practically all his writing dealr with the life of the commofl people of Beijing. -

Performability and Translation : a Case Study of the Production and Reception of Ying Ruocheng’S Translations

Lingnan University Digital Commons @ Lingnan University Theses & Dissertations Department of Translation 8-26-2016 Performability and translation : a case study of the production and reception of Ying Ruocheng’s translations Yichen YANG Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/tran_etd Part of the Applied Linguistics Commons, and the Translation Studies Commons Recommended Citation Yang, Y. (2016). Performability and translation: A case study of the production and reception of Ying Ruocheng’s translations (Doctor's thesis, Lingnan University, Hong Kong). Retrieved from http://commons.ln.edu.hk/tran_etd/17 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Translation at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. Terms of Use The copyright of this thesis is owned by its author. Any reproduction, adaptation, distribution or dissemination of this thesis without express authorization is strictly prohibited. All rights reserved. PERFORMABILITY AND TRANSLATION A CASE STUDY OF THE PRODUCTION AND RECEPTION OF YING RUOCHENG’S TRANSLATIONS YANG YICHEN PHD LINGNAN UNIVERSITY 2016 PERFORMABILITY AND TRANSLATION A CASE STUDY OF THE PRODUCTION AND RECEPTION OF YING RUOCHENG’S TRANSLATIONS by YANG Yichen 杨祎辰 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Translation Lingnan University 2016 ABSTRACT Performability and Translation A Case Study of the Production and Reception of Ying Ruocheng’s Translations by YANG Yichen Doctor of Philosophy The active scholarly contribution made by practitioners of theatre translation in the past decades has turned the research area into what is now considered a burgeoning field. -

98 Saffron Walkling: Coriolanus, Edinburgh International Festival

98 Theatre Reviews Saffron Walkling: Coriolanus, Edinburgh International Festival. Dir. Lin Zhaohua, 20-21 August 2013. A Chinese Coriolanus and British Reception: A Play Out of Context? Lin Zhaohua’s Coriolanus, translated by Ying Roucheng, and retitled in Chinese as Great General Kou Liulan, was originally performed by the Beijing People’s Art Theatre1 in the Chinese capital in 2007. It played at the Edinburgh International Festival last August for “two days only” – and four thousand ticket holders came to see it. Born in 1936 and emerging as a director after the chaos of the Cultural Revolution, Lin is now recognized as “one of the most innovative and sought-after stage directors in contemporary China” (Fei 179). No wonder that the British media and audiences turned to this production, or so it seems, to learn about the world’s new Superpower as much as to go to see a play by Shakespeare. Dominic Cavendish in The Daily Telegraph described it as being a milestone “on that all-important journey towards better cross-cultural understanding” (“Edinburgh Festival 2013: The Tragedy of Coriolanus, Playhouse, review”) while Lyn Gardner of The Guardian complained that it seemed “determined to offer no comment on the society that spawned it” (“The Tragedy of Coriolanus – Edinburgh Festival 2013 review”). This ethnographic gaze is not surprising. During my interview with Lin Zhaohua in 2011, when I was in Beijing researching his work on Shakespeare appropriation, he told me excitedly that he had just been in discussion with “a man from Edinburgh” (personal communication, 2011). But how would Coriolanus fare when transferred to the Scottish stage, my Chinese interpreter wondered afterwards? “Will Westerners be able to understand him?” she asked me. -

The Global Dimension of Bertolucci's The

From Beijing with love: The global dimension of Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor Baschiera, S. (2014). From Beijing with love: The global dimension of Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor. Journal of Italian Cinema & Media Studies, 2(3), 399-415. https://doi.org/10.1386/jicms.2.3.399_1 Published in: Journal of Italian Cinema & Media Studies Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2014 Journal of Italian Cinema & Media Studies General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:28. Sep. 2021 From Beijing with love: the global dimension of Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor Stefano Baschiera, Queen’s University Belfast DOI 10.1386/jicms.2.3.399_1 Intellect: Journal of Italian Cinema & Media Studies, Volume 2, Number 3, September 2014, pp. 399-415(17) Abstract Famous for being the first foreign feature film that obtained permission to shoot in the Forbidden City, The Last Emperor (1987) is also one of the most ambitious and expensive independent productions of its time, awarded four Golden Globes and nine Academy Awards, including Best Picture. -

Study of Marxist Philosophy Urged

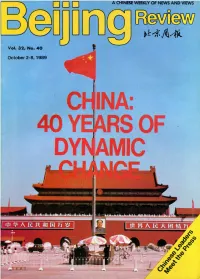

RSOF BEIJING REVIEW VOL. 32, NO. 40 OCT. 2-8, 1989 CONTENTS Chinese Leaders on Domestic and Foreign Affairs EVENTS/TRENDS 4-9 China Protests France's Support For Fugitives • At a press conference held on September 26 in Beijing and Study of Marxist Philosophy attended by all members of the Standing Committee of the CPC Urged Political Bureau, Party General Secretary Jiang Zemin and Premier Deng on Handling International Li Peng met Chinese and foreign journalists. Full text of the Relations conference (p. 15). CPPCC Marked 40th Aniversary Leader Explains Policies to HK Journalists French Interference Protested Deng on Handling international Relations Taiwan Renounced for Propaganda Trick Quality of Party Members to Be • While meeting Masayoshi Ito in Beijing, senior Chinese leader Improved Deng Xiaoping said the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence Publications Will Be Streamlined News in Brief should be the guideline for settling international political and eco• INTERNATIONAL nomic problems. He told Ito that no matter what happens in the China's Foreign Trade in Past 40 world, the friendship between China and Japan must not change and Years 10 will not change (p. 5). CHINA Top Party Leaders Answer Questions at Press Conference 15 Only Socialism Can Develop China Only Socialism Can Develop China 19 China Advances Towards Its • China has attained notable achievements of economic develop• 40th Anniversary 26 ment and improvement in the standard of living over the pjst four Ordinary People of the People's decades. These successes are impossible for China without the Republic 35 leadership of the Chinese Communist Party, the socialist system, the 'Present Policies Are Best' political power at the service of the people and the public ownership 'My Dream Comes True' A Private Entrepreneur's of the means of production. -

Portrayal of Tibetan Buddhism in Hollywood Movies

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Bakalářská diplomová práce 2013 Sylvie Mynarčíková Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Sylvie Mynarčíková Portrayal of Tibetan Buddhism in Hollywood Movies Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: doc. PhDr. Tomáš Pospíšil, Dr. 2013 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature Acknowledgement I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor doc. PhDr. Tomáš Pospíšil, Dr., for his guidance and time. I am grateful for his helpful suggestions and valuable advice. Table of Contents 1 Introduction.................................................................................................................1 2 Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism............................................................................3 2.1.The Fourteenth Dalai Lama.................................................................................6 2.2 Teachings........................................................................................................... 9 3 Buddhism in America.............................................................................................. 12 4 Kundun...................................................................................................................... 16 5 Little Buddha............................................................................................................ -

Human Rights in the People's Republic of China, 1986/1987

OccAsioNAl PApERs/ REpRiNTS SERiEs 0 iN CoNTEMpORARY 'I AsiAN STudiEs NUMBER 6 - 1987 {83) REFORM IN REVERSE: HUMAN RIGHTS , IN THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA, ••' 1986/1987 Ta-Ling Lee and John F. Copper ScltoolofLAw UNivERsiTy of MARylANd. - ' Occasional Papers/Reprint Series in Contemporary Asian Studies General Editor: Hungdah Chiu Executive Editor: Jaw-ling Joanne Chang Managing Editor: Chih-Yu Wu Editorial Advisory Board Professor Robert A. Scalapino, University of California at Berkeley Professor Martin Wilbur, Columbia University Professor Shao-chuan Leng, University of Virginia Professor James Hsiung, New York University Dr. Lih-wu Han, Political Science Association of the Republic of China Professor J. S. Prybyla, The Pennsylvania State University Professor Toshio Sawada, Sophia University, Japan Professor Gottfried-Karl Kindermann, Center for International Politics, University of Munich, Federal Republic of Germany Professor Choon-ho Park, International Legal Studies Korea University, Republic of Korea All contributions (in English only) and communications should be sent to Professor Hungdah Chiu, University of Maryland School of Law, 500 West Baltimore Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201 USA. All publications in this series reflect only the views of the authors. While the editor accepts responsibility for the selection of materials to be published, the individual author is responsible for statements of facts and expressions of opinion con tained therein. Subscription is US $15.00 for 6 issues (regardless of the price of individual issues) in the United States and Canada and $20.00 for overseas. Check should be addressed to OPRSCAS and sent to Professor Hungdah Chiu. Price for single copy of this issue: US $8.00 © 1987 Occasional Papers/Reprints Series in Contemporary Asian Studies, Inc. -

An Extraordinary Life Ill and Was Hospitalized

38 | Lexington’s Colonial Times Magazine FEBRUARY | MARCH 2009 Copyright CTM Publishing An Extraordinary Life ill and was hospitalized. But just as significant as his acting career, Ying was a writer, a translator, and a stage director. He was a founding member of the Beijing People’s Art Theatre. He was a high- ranking politician, the vice minister of culture from 1986 to 1990. Evidence after his death proved he was also a spy. Indicative of his personality, Ying begins his story by writing, “The most interesting part of my life, I’m afraid, is when I Claire Conceison holds her book, Voices Carry: Behind Bars was arrested in 1968 and imprisoned for three years.” He and and Backstage during China’s Revolution and Reform. his actress/translator wife Wu Shiliang were both imprisoned during the tumultuous times of the Cultural Revolution. Unlike By Judy Buswick other books delineating the hardships endured in Chinese prisons, Ying tells how he learned about the lives and careers of other prisoners and “about China’s true state of affairs.” He When the producer of a television mini-series titled Marco used his creativity and personality to influence guards and make Polo needed an English-speaking actor to play Kublai Khan, prison life somewhat easier for himself and for other prisoners. renowned playwright Arthur Miller knew just the Asian man Upon his release, he returned to the theatre and adapted to the A Chinese postcard honoring Ying Roucheng to suggest. Success in that role led the stage actor to featured as “a famous modern drama actor.” new regime. -

![Curriculum Vitae: KANG-I SUN CHANG Æ]±D©Y](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0578/curriculum-vitae-kang-i-sun-chang-%C3%A6-%C2%B1d%C2%A9y-8800578.webp)

Curriculum Vitae: KANG-I SUN CHANG Æ]±D©Y

CURRICULUM VITAE Kang-i Sun Chang 孫 康 宜 Kang-I Sun Chang: Short Bio Kang-i Sun Chang (孫康宜), the inaugural Malcolm G. Chace ’56 Professor of East Asian Languages and Literatures at Yale University, is a scholar of classical Chinese literature with interest in comparative studies of poetry, literary criticism, gender studies, and cultural theory / aesthetics. The Chace professorship was established by Malcolm “Kim” G. Chace III ’56, “to support the teaching and research activities of a full-time faculty member in the humanities, and to further the University’s preeminence in the study of arts and letters.” Chang is the author of The Evolution of Chinese Tz’u Poetry: From Late Tang to Northern Sung; Six Dynasties Poetry; The Late Ming Poet Ch’en Tzu-lung: Crises of Love and Loyalism; and Journey Through the White Terror. She is the co-editor of Writing Women in Late Imperial China (with Ellen Widmer), Women Writers of Traditional China (with Haun Saussy), and The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature (with Stephen Owen). Her translations have been published in a number of Chinese publications, and she has also authored books in Chinese, including Wenxue jingdian de tiaozhan (Challenges of the Literary Canon), Wenxue de shengyin (Voices of Literature), Zhang Chonghe tizi xuanji (Calligraphy of Ch’ung-ho Chang Frankel: Selected Inscriptions), Quren hongzhao (Artistic and Cultural Traditions of the Kunqu Musicians), and Wo kan Meiguo jingshen (My Thoughts on the American Spirit). Her current book project is tentatively titled, “Shi Zhecun: A Modernist Turned Classicist.” At Yale, Chang is on the affiliated faulty of the Literature Major (at the Department of Comparative Literature) and is also on the faculty associated with Women’s and Gender Studies Program.