Stress Assignment in Words with -I Suffix in Hebrew Ora (Rodrigue) Schwarzwald, Bar-Ilan University, Israel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Things That Concordances Do Not Tell You

358 The Testimony, September 2001 “walk away” is indicative of the hold which John Paul II and the Palestinian leader Yasser the Middle East has on the nations of the world. Arafat. As events continue to develop in the Mid- The article goes on to write of how the European dle East we should exhort one another as we see Union has been involved and how (in MacAskill’s the day approaching (Heb. 10:25). Let us remain opinion) there is scope for more involvement in faithful so that we might be with Christ as he the crisis. The Catholic Church is also increas- marches through Bozrah (Isa. 34:6) and moves to ingly becoming involved in the crisis. On 2 Au- Israel to carry out the “recompences for the con- gust 2001 a meeting took place between Pope troversy of Zion” (v. 8). 1234 1234 1234 EDITOR: John Nicholls, 17 Upper Trinity Road, Halstead, 1234 1234 1234 Essex, CO9 1EE. Tel. 01787 473089; 1234 1234 e-mail: [email protected] 1234 1234 Reviews 1234 1234 Some things that concordances do not tell you John Carder N ENGLISH the tense of a verb shows its That form is often referred to as the stem or root relation to time, that is, past tense, present of the verb. Itense or future tense. English is a very time- From that basic and most simple form, usu- orientated language, with distinct tenses. The ally consisting of just three Hebrew letters, all Hebrew of the Bible is completely different. It other parts of each Hebrew verb are derived. -

Inflectional and Derivational Hebrew Morphology According to the Theory of Phonology As Human Behavior

BEN- GURION UNIVERSITY OF THE NEGEV FACULTY OF HUMINITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF FOREIGN LITERATURES AND LINGUISTICS INFLECTIONAL AND DERIVATIONAL HEBREW MORPHOLOGY ACCORDING TO THE THEORY OF PHONOLOGY AS HUMAN BEHAVIOR THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS LINA PERELSHTEIN UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF: PROFESSOR YISHAI TOBIN FEBRUARY 2008 BEN- GURION UNIVERSITY OF THE NEGEV FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF FOREIGN LITERATURES AND LINGUISTICS INFLECTIONAL AND DERIVATIONAL HEBREW MORPHOLOGY ACCORDING TO THE THEORY OF PHONOLOGY AS HUMAN BEHAVIOR THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS LINA PERELSHTEIN UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROFESSOR YISHAI TOBIN Signature of student: ________________ Date: _________ Signature of supervisor: _____________ Date: _________ Signature of chairperson of the committee for graduate studies: ______________ Date: _________ FEBRUARY 2008 ABSTRACT This research deals with the phonological distribution of Hebrew Inflectional and Derivational morphology, synchronically and diachronically. The scope of this study is suffixes, due to the fact that final position bears grammatical information, while initial position bears lexical items. In order to analyze the gathered data, the theory of Phonology as Human Behavior will be employed. The theory classifies language as a system of signs which is used by human beings to communicate; it is based on the synergetic principle of maximum communication with minimal effort. This research shows that the similarity within Modern Hebrew inflectional and derivational suffix system is greater than the derivational Modern Hebrew – Biblical Hebrew system in terms of a specialized suffix system and that the phonological distribution of Hebrew suffixes is motivated by the principles of the theory. -

How Was the Dageš in Biblical Hebrew Pronounced and Why Is It There? Geoffrey Khan

1 pronounced and why is it בָּתִּ ים How was the dageš in Biblical Hebrew there? Geoffrey Khan houses’ is generally presented as an enigma in‘ בָּתִּ ים The dageš in the Biblical Hebrew plural form descriptions of the language. A wide variety of opinions about it have been expressed in Biblical Hebrew textbooks, reference grammars and the scholarly literature, but many of these are speculative without any direct or comparative evidence. One of the aims of this article is to examine the evidence for the way the dageš was pronounced in this word in sources that give us direct access to the Tiberian Masoretic reading tradition. A second aim is to propose a reason why the word has a dageš on the basis of comparative evidence within Biblical Hebrew reading traditions and other Semitic languages. בָּתִּיםבָּתִּ ים The Pronunciation of the Dageš in .1.0 The Tiberian vocalization signs and accents were created by the Masoretes of Tiberias in the early Islamic period to record an oral tradition of reading. There is evidence that this reading tradition had its roots in the Second Temple period, although some features of it appear to have developed at later periods. 1 The Tiberian reading was regarded in the Middle Ages as the most prestigious and authoritative tradition. On account of the authoritative status of the reading, great efforts were made by the Tiberian Masoretes to fix the tradition in a standardized form. There remained, nevertheless, some degree of variation in reading and sign notation in the Tiberian Masoretic school. By the end of the Masoretic period in the 10 th century C.E. -

Preliminary Studies in the Judaean Desert Isaiah Scrolls and Fragments

INCORPORATING SYNTAX INTO THEORIES OF TEXTUAL TRANSMISSION: PRELIMINARY STUDIES IN THE JUDAEAN DESERT ISAIAH SCROLLS AND FRAGMENTS by JAMES M. TUCKER A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Master of Arts in Biblical Studies We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard ............................................................................... Dr. Martin G. Abegg Jr., Ph.D.; Thesis Supervisor ................................................................................ Dr. Dirk Büchner, Ph.D.; Second Reader TRINITY WESTERN UNIVERSITY Date (August, 2014) © James M. Tucker TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations and Sigla i Abstract iv Chapter 1: Introduction 1 1.0. Introduction: A Statement of the Problem 1 1.1. The Goal and Scope of the Thesis 5 Chapter 2: Methodological Issues in the Transmission Theories of the Hebrew Bible: The Need for Historical Linguistics 7 2.0. The Use of the Dead Sea Scrolls Evidence for Understanding The History of ! 7 2.1. A Survey and Assessment of Transmission Theories 8 2.1.1. Frank Moore Cross and the Local Text Theory 10 2.1.1.1. The Central Premises of the Local Text Theory 11 2.1.1.2. Assessment of the Local Text Theory 14 2.1.2. Shemaryahu Talmon and The Multiple Text Theory 16 2.1.2.1. The Central Premises of the Multiple Texts Theory 17 2.1.2.2. Assessment of Multiple Text Theory 20 2.1.3. Emanuel Tov and The Non-Aligned Theory 22 2.1.3.1 The Central Premises of the Non-Aligned Theory 22 2.1.3.2. Assessment of the Non-Aligned Theory 24 2.1.4. -

HEADS HEBREW Graml\Iar

HEADS OF HEBREW GRAMl\iAR HE1tDS OF IIEilRE\V GRAJ\ilJ\lAR CONTAINING ALL THE PRINCIPLES NEEDED BY A LEARNER. BY S. PRIDEAUX TREGELLES, LL.D. TWENTY-THIRD IMPRESSION SAMUEL BAGSTER & SONS LTD. 80 WIGMORE STREET LONDON WI NEW YORK: HARPER AND BROTHERS ..?'RINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN PREFACE. - THE object of these Heads of Hebrew Grammar is to furnish the learner of that language with all that is noedful for him in his introductory studies, so that he may be thoroughly grounded in all that is elementary. In teaching, the present writer has been wont to give oral imtruction as to all the elements, commonly making use of some short Hebrew grammar ;--marking tl,e rules which re quire attent10n, and adding others which are not to be found in elementary grammars in general. In this way he has had a kind of oral Hebrew grammar for learners; and the same grammatical instruction which he has thus communicated to those whom he has thus taught, is here given w-ritten down for use or reference. He is well aware that the number of Hebrew grammars, both of those called elementary, and of those called critical, -is very great; this consideration made him long feel reluc tant to commit his oral grammatical instruction to writing; but, if the mass of He\Jrew grammars be examined, it will be found that very few of them possess any distinctive features; and he is not aware of one which he has been able to use as thoroughly adapted to the want,s of learners. -

Chastised Rulers in the Ancient Near East

Chastised Rulers in the Ancient Near East Dissertation Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree doctor of philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By J. H. Price, M.A., B.A. Graduate Program in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Samuel A. Meier, Advisor Daniel Frank Carolina López-Ruiz Bill T. Arnold Copyright by J. H. Price 2015 Abstract In the ancient world, kings were a common subject of literary activity, as they played significant social, economic, and religious roles in the ancient Near East. Unsurprisingly, the praiseworthy deeds of kings were often memorialized in ancient literature. However, in some texts kings were remembered for criminal acts that brought punishment from the god(s). From these documents, which date from the second to the first millennium BCE, we learn that royal acts of sacrilege were believed to have altered the fate of the offending king, his people, or his nation. These chastised rulers are the subject of this this dissertation. In the pages that follow, the violations committed by these rulers are collected, explained, and compared, as are the divine punishments that resulted from royal sacrilege. Though attestations are concentrated in the Hebrew Bible and Mesopotamian literature, the very fact that the chastised ruler type also surfaces in Ugaritic, Hittite, and Northwest Semitic texts suggests that the concept was an integral part of ancient near eastern kingship ideologies. Thus, this dissertation will also explain the relationship between kings and gods and the unifying aspect of kingship that gave rise to the chastised ruler concept across the ancient Near East. -

Remarks on the Development of Some Pronominal Suffixes in Hebrew

REMARKS ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF SOME PRONOMINAL SUFFIXES IN HEBREW by JOSHUA BLAU Hebrew University, Jerusalem ABSTRACT: The paradigmatic pressure for the preservation of the final vowels of pronominal suffixes after long vowels, where gender opposition could not be marked by the preceding vowel, was strong enough to create in rabbinic Hebrew, in Aramaic, and in Arabic, dialect doublets, viz., suffixes without final vowel after originally short vowels (as rabbinic He brew yadak 'your hand'), and those with final vowels after long vowels (as yadeKa 'your hands'). 1. In Hebrew Annual Review, R. C. Steiner ( 1979), among a plethora of stimulating observations, dealt with the 2ms and 3fs pronominal suffixes in biblical and rabbinic Hebrew. In the following, I would like to consider these features from somewhat different angles. 2. As to the 2ms pronominal suffix, in biblical Hebrew in context it invariably terminates in -ka, e.g. yad;Jka 'your hand', in pause either in -ak, e.g. lak 'to you', or, as a rule, in -eka, e.g. yadeka. In rabbinic Hebrew, on the other hand, its usual form is -ak, e.g. yadak, after bases ending in a vowel -ka, e.g. yadeka 'your hands' (for particulars, see Steiner 1979, p. 158). The prevalence of the -ak type in rabbinic Hebrew reflects an Aramaism, according to Ben-Hayyim (1954, pp. 63f); Steiner (p. 162) mentions as an additional factor the tendency of biblical Hebrew pausal forms to spread into nonpausal positions in rabbinic Hebrew. Both expla nations, however, cannot be considered decisive, Ben-Hayyim's view, be cause the distribution of-akin rabbinic Hebrew differs significantly from that in Aramaic (as pointed out by Steiner, pp. -

Relationships Between Metalinguistic and Spelling Development Across Languages : Evidence from English and Hebrew

RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN METALINGUISTIC AND SPELLING DEVELOPMENT ACROSS LANGUAGES: EVIDENCE FROM ENGLISH AND HEBREW Miriam Ruth Bindman Child Development and Learning Institute of Education University of London Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 1997 2 ABSTRACT Metalinguistic awareness is transferable between oral and written forms of language, and between different languages. Recent research has established a connection between monolingual children's grammatical awareness and their morphological spelling knowledge. Studies of bilingual children have shown that phonological awareness and alphabetic knowledge transfer across languages, even if the languages are dissimilar and are written with different scripts. This study investigates transfer of grammatical awareness and morphological spelling knowledge across dissimilar languages and scripts. In spoken language, children learn not only surface-level language 'facts' specific to that language (e.g. vocabulary) but also deeper-level grammatical principles (e.g. morphological and syntactic relationships), which govern other languages. Similarly, literacy requires surface-level knowledge of a specific script (e.g. letters and their sound values), and knowledge of the principle underlying that script (e.g. that alphabets represent phonology and morphology), which governs other scripts of the same type. I propose that transfer across languages occurs at the level of grammatical awareness but not at the level of vocabulary. The hypothesis was tested in English- speaking children (6-11 years) learning Hebrew as a second language. In Study 1, Hebrew learners were given oral measures of vocabulary and grammatical awareness, and measures of morphological spelling knowledge. Grammatical awareness and morphological spelling knowledge were significantly correlated across languages, but vocabulary was not. -

Issues in the Representation of Pointed Hebrew in Unicode

Issues in the Representation of Pointed Hebrew in Unicode http://www.qaya.org/academic/hebrew/Issues-Hebrew-Unicode.html Issues in the Representation of Pointed Hebrew in Unicode Third draft, Peter Kirk, August 2003 1. Introduction The Hebrew block of the Unicode Standard (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U0590.pdf) is intended to include all of the characters needed for proper representation of Hebrew texts from all periods of the Hebrew language, including fully pointed and cantillated ancient texts such as that of the Hebrew Bible. It is also intended to cover other languages 1 written in Hebrew script, including Aramaic as used in biblical and other religious texts as well as Yiddish and a few other modern languages. In practice there are a number of issues and minor deficiencies in the Hebrew block as currently defined, in version 4.0 of the Unicode Standard (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode4.0.0/), which affect its usefulness for representation of pointed Hebrew texts and of Hebrew script texts in some other languages. Some of these simply require clarification and agreed guidelines for implementers. Others require further discussion and decision, and possibly additions to the Unicode standard or other action by the Unicode Technical Committee. The conclusion reached in this paper is that two new Unicode characters should be proposed; other issues can be resolved by use of suitable sequences of existing characters, provided that such use is generally agreed by content providers and rendering systems. Several of these issues relate to different typographical conventions for publishing of Hebrew texts. -

Morphologically Conditioned V–Ř Alternation in Hebrew

Morphologically conditioned V–Ø alternation in Hebrew Distinction among nouns, adjectives & participles, and verbs* Outi Bat-El Department of Linguistics Tel-Aviv University I argue in this paper that phonology plays a role in enhancing the distinction among the lexical categories. The argument is based on V–Ø alternation in the inflectional paradigms of CVCVC stems which varies in position and type of vowel depending on the lexical category. For example, adjectives exhibit a–Ø alternation in the penultimate syllable, while verbs in the final syllable. The Optimality Theoretic analysis reveals that the phonological difference among the lexical categories is minimal (one unique ranking of two constraints for each category), allowing a category distinction without a major increase in the complexity of the phonological system. Keywords: Hebrew morpho-phonology; vowel-zero alternation; category- specific phonology; lexical categories; lexical representation; paradigmatic relations; Optimality Theory 1. Introduction In this paper I examine the manifestation of V–Ø alternation in four lexical cat- egories in Modern Hebrew: nouns, adjectives, participles, and verbs. I argue that this alternation distinguishes among three groups of lexical categories: (i) nouns, (ii) adjectives and participles, and (iii) verbs. This morpho-phonological distinc- tion is demonstrated using an Optimality Theoretic analysis, where each group has one unique ranking of two constraints. *Earlier versions of this paper were given at Tel-Aviv University and Ben-Gurion -

The British-Israel Myth - Christian Identity and the Lost Tribes of Israel

The British-Israel Myth - Christian Identity and the Lost Tribes of Israel Nick Greer Copyright © September 2004. All rights reserved. This document is hereby made freely available for the use of any and all worldwide. Permission is granted to anyone to make or distribute verbatim copies of this document, in any medium, provided that, except with written permission, the text remains unaltered, and this copyright notice and permission notice are preserved. Except with written permission, no charge whatsoever for redistribution may be made. Paperback editions of this book, and the most recent electronic editions, are available from the Internet at www.pengo.us Unless Otherwise Indicated, the Scripture quotations contained herein are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright 1989, by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A. Used by permission. All rights reserved. CONTENTS 1 Introduction ..................................................................7 2 British-Israelism Doctrine ..........................................11 2.1 Scattering of the Tribes..........................................11 2.2 The British-Israel Chronology ...............................14 2.3 Richard Brothers ....................................................15 3 British-Israelism Examined by Scripture....................17 3.1 Accounts of the Tribe’s Return..............................17 3.2 King Cyrus.............................................................18 3.3 Unification of Assyria -

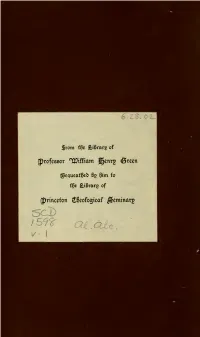

A Grammar of the Hebrew Language

6,Z5VO/ Stom t^e £i6rare of Q^equeaf^e^ fig ^im to t^e feifirarg of (Princeton C^eofo^caf ^emtndtg 1/. I GRAMMAR OF TPTE HEBREW LANGUAGE. BY / WILLIAM HENRY GREEN, PROFESSOR IN THE THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY AT PRINCETON, N. J. jarto ISiJttton. (CAREFULLY RKVISED THROUGHOUT AND THE SYNTAX GREATLY ENLARGED. Part I.— Orthoaraphy and. Etyixiology. NEW YORK: JOHN WILEY & SONS, PUBLISHERS, 15 AsTOR Place. 1888. Copyright, 1888, by JOHN WILEY & SONSk PREFACE. The twenty-seven years, which have elapsed since the first publication of this Grammar, have been exceed- ingly fruitful in the philological and exegetical study of the Old Testament. And important progress has been made toward a more thorough and accurate knowledge of the grammatical structure of the Hebrew language. This edition of the Grammar has been carefully revised throughout that it may better represent the advanced state of scholarship on this subject. Nearly every page exhibits corrections or additions of greater or less conse- quence. And the Syntax particularly, which was not fully elaborated before, has been greatly enlarged, and for the most part entirely rewritten. The plan of the Grammar, the method of treatment, and in general the order of the sections are unchanged. And little occasion has been found to alter the more general and comprehen- sive statements, which are distinguished by being printed in large type. The changes are chiefly in the addition of fuller details enlarging and multiplying the para- graphs in small type. The principle of eschewing all supposititious forms and adducing none but such as really occur in the Old Testa- ment, has been steadfastly adhered to as heretofore, with the view of rigorously conforming all rules and examples to the actual phenomena of the language.