Zhang Hongtu Interview Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zhang Hongtu / Hongtu Zhang: an Interview'

An Interview with Zhang Hongtu 281 the roots - Chinese culture - had already become part of my life just as a tail is a part of a dog's body. I'm like a dog: the tail will be with me for 10 ever, no matter where I go. Sure, after nine years away from China, I forget many things, like I forget that when you buy lunch you have to pay Zhang Hongtu / Hongtu Zhang: ration coupons with the money, and how much political pressure there An Interview' was in my everyday life. But because I still keep reading Chinese books and thinking about Chinese culture, and especially because I have the opportunity to see the differences between Chinese culture and the Western culture which I learned about after I left China, my image of Chinese culture has become more clear. Su Dongpo (the poet, I036- Zhang Hongtu was born in Gansu province, in northwest China, in lIOI) said: Bu shi Lushan zhen mianmu / Zhi yuan shen zai si shan I943, but grew up in Beijing. After studies at the Central Academy of zbong, Which means, one can't see the image of Mt. Lu because one is Arts and Crafts in Beijing, he was later assigned to work as a design inside the mountain. Now that I'm outside of the mountain, I can see supervisor in a jewellery company. In I982, he left China to pursue a what the image of the mountain is, so from this point of view I would say career as a painter in New York. -

Joan Lebold Cohen Interview Transcript

www.china1980s.org INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT JOAN LEBOLD COHEN Interviewer: Jane DeBevoise Date:31 Oct 2009 Duration: about 2 hours Location: New York Jane DeBevoise (JD): It would be great if you could speak a little bit about how you got to China, when you got to China – with dates specific to the ‘80s, and how you saw the 80’s develop. From your perspective what were some of the key moments in terms of the arts? Joan Lebold Cohen (JC): First of all, I should say that I had been to China three times before the 1980s. I went twice in 1972, once on a delegation in May for over three weeks, which took us to Beijing, Luoyang, Xi’an, and Shanghai and we flew into Nanchang too because there were clouds over Guangzhou and the planes couldn’t fly in. This was a period when, if you wanted to have a meal and you were flying, the airplane would land so that you could go to a restaurant (Laughter). They were old, Russian airplanes, and you sat in folding chairs. The conditions were rather…primitive. But I remember going down to the Shanghai airport and having the most delicious ‘8-precious’ pudding and sweet buns – they were fantastic. I also went to China in 1978. For each trip, I had requested to meet artists and to go to exhibitions, but was denied the privilege. However, there was one time, when I went to an exhibition in May of 1972 and it was one of the only exhibitions that exhibited Cultural Revolution model paintings; it was very amusing. -

Summer 2020 Degrees Conferred

THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Degrees Conferred SUMMER SEMESTER 2020 Data as of November 17, 2020 Australia Sorted by Zip Code, City and Last Name Degree Student Name (Last, First, Middle) City State Zip Degree Honor Fofanah, Osman Ngunnawal 2913 Bachelor of Science in Education THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY OSAS - Analysis and Reporting November 17, 2020 Page 1 of 42 THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Degrees Conferred SUMMER SEMESTER 2020 Data as of November 17, 2020 Bangladesh Sorted by Zip Code, City and Last Name Degree Student Name (Last, First, Middle) City State Zip Degree Honor Helal, Abdullah Al Dhaka 1217 Master of Science Alam, Md Shah Comilla 3510 Master of Science THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY OSAS - Analysis and Reporting November 17, 2020 Page 2 of 42 THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Degrees Conferred SUMMER SEMESTER 2020 Data as of November 17, 2020 Bolivia Sorted by Zip Code, City and Last Name Degree Student Name (Last, First, Middle) City State Zip Degree Honor Arrueta Antequera, Lourdes Delta El Alto Master of Science THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY OSAS - Analysis and Reporting November 17, 2020 Page 3 of 42 THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Degrees Conferred SUMMER SEMESTER 2020 Data as of November 17, 2020 Brazil Sorted by Zip Code, City and Last Name Degree Student Name (Last, First, Middle) City State Zip Degree Honor dos Santos Marques, Ana Carolina Sao Jose Do Rio Pre 15015 Doctor of Philosophy Marotta Gudme, Erik Rio De Janeiro 22460 Bachelor of Science in Business Administration Magna Cum Laude Pereira da Cruz Benetti, Lucia Porto Alegre 90670 Doctor -

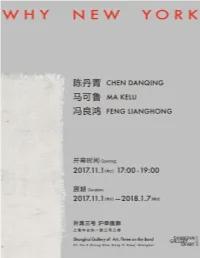

WHY-NEW-YORK-Artworks-List.Pdf

“Why New York” 是陈丹青、马可鲁、冯良鸿三人组合的第四次展览。这三位在中国当代艺术的不同阶 段各领风骚的画家在1990年代的纽约聚首,在曼哈顿和布鲁克林既丰饶又严酷的环境中白手起家,互 相温暖呵护,切磋技艺。到了新世纪,三人不约而同地回到中国,他们不忘艺术的初心,以难忘的纽约 岁月为缘由,频频举办联展。他们的组合是出于情谊,是在相互对照和印证中发现和发展各自的面目, 也是对艺术本心的坚守和砥砺。 不同于前几次带有回顾性的展览,这一次三位艺术家呈现了他们阶段性的新作。陈丹青带来了对毕加 索等西方艺术家以及中国山水及书法的研究,他呈现“画册”的绘画颇具观念性,背后有复杂的摹写、转 译、造型信息与图像意义的更替演化等话题。马可鲁的《Ada》系列在“无意识”中蕴含着规律,呈现出 书写性,在超越表面的技巧和情感因素的画面中触及“真实的自然”。冯良鸿呈现了2012年以来不同的 几种方向,在纯色色域的覆盖与黑白意境的推敲中展现视觉空间的质感。 在为展览撰写的文章中,陈丹青讲述了在归国十余年后三人作品中留有的纽约印记。这三位出生于上海 的画家此次回归家乡,又一次的聚首凝聚了岁月的光华,也映照着他们努力前行的年轻姿态。 “Why New York” marks the fourth exhibition of the artists trio, Chen Danqing, Ma Kelu and Feng Lianghong. Being the forerunners at the various stages in the progress of Chinese contemporary art, these artists first met in New York in the 1990s. In that culturally rich yet unrelenting environment of Manhattan and Brooklyn, they single-handedly launched their artistic practice, provided camaraderie to each other and exchanged ideas about art. In the new millennium, they’ve returned to China respectively. Bearing in mind their artistic ideals, their friendship and experiences of New York reunite them to hold frequent exhibitions together. With this collaboration built on friendship, they continue to discover and develop one’s own potential through the mirror of the others, as they persevere and temper in reaching their ideals in art. Unlike the previous retrospective exhibitions, the artists present their most recent works. Chen Danqing’s study on Picasso and other Western artists along with Chinese landscape painting and calligraphy is revealed in his conceptual painting “Catalogue”, a work that addresses the complex notions of drawing, translation, compositional lexicon and pictorial transformation. Ma Kelu’s “Ada” series embodies a principle of the “unconscious”, whose cursive and hyper expressive techniques adroitly integrates with the emotional elements of the painting to render “true nature”. -

The Aesthetic and Ethic of the Chinese Diasporic Artist Mu Xin

“Art Is to Sacrifice One’s Death”: The Aesthetic and Ethic of the Chinese Diasporic Artist Mu Xin by Muyun Zhou Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Carlos Rojas, Supervisor ___________________________ Eileen Chow ___________________________ Leo Ching Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Critical Asian Humanities in the Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2021 ABSTRACT “Art Is to Sacrifice One’s Death”: The Aesthetic and Ethic of the Chinese Diasporic Artist Mu Xin by Muyun Zhou Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Carlos Rojas, Supervisor ___________________________ Eileen Chow ___________________________ Leo Ching An abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Critical Asian Humanities in the Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2021 Copyright by Muyun Zhou 2021 Abstract In his world literature lecture series running from 1989 to 1994, the Chinese diasporic writer-painter Mu Xin (1927-2011) provided a puzzling proposition for a group of emerging Chinese artists living in New York: “Art is to sacrifice.” Reading this proposition in tandem with Mu Xin’s other comments on “sacrifice” from the lecture series, this study examines the intricate relationship between aesthetics and ethics in Mu Xin’s project of art. The question of diasporic positionality is inherent in the relationship between aesthetic and ethical discourses, for the two discourses were born in a Western tradition, once foreign to Mu Xin. -

Independent Cinema in the Chinese Film Industry

Independent cinema in the Chinese film industry Tingting Song A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Creative Industries Queensland University of Technology 2010 Abstract Chinese independent cinema has developed for more than twenty years. Two sorts of independent cinema exist in China. One is underground cinema, which is produced without official approvals and cannot be circulated in China, and the other are the films which are legally produced by small private film companies and circulated in the domestic film market. This sort of ‘within-system’ independent cinema has played a significant role in the development of Chinese cinema in terms of culture, economics and ideology. In contrast to the amount of comment on underground filmmaking in China, the significance of ‘within-system’ independent cinema has been underestimated by most scholars. This thesis is a study of how political management has determined the development of Chinese independent cinema and how Chinese independent cinema has developed during its various historical trajectories. This study takes media economics as the research approach, and its major methods utilise archive analysis and interviews. The thesis begins with a general review of the definition and business of American independent cinema. Then, after a literature review of Chinese independent cinema, it identifies significant gaps in previous studies and reviews issues of traditional definition and suggests a new definition. i After several case studies on the changes in the most famous Chinese directors’ careers, the thesis shows that state studios and private film companies are two essential domestic backers for filmmaking in China. -

Chinese Contemporary Art-7 Things You Should Know

Chinese Contemporary Art things you should know By Melissa Chiu Contents Introduction / 4 1 . Contemporary art in China began decades ago. / 14 2 . Chinese contemporary art is more diverse than you might think. / 34 3 . Museums and galleries have promoted Chinese contemporary art since the 1990s. / 44 4 . Government censorship has been an influence on Chinese artists, and sometimes still is. / 52 5 . The Chinese artists’ diaspora is returning to China. / 64 6 . Contemporary art museums in China are on the rise. / 74 7 . The world is collecting Chinese contemporary art. / 82 Conclusion / 90 Artist Biographies / 98 Further Reading / 110 Introduction 4 Sometimes it seems that scarcely a week goes by without a newspaper or magazine article on the Chinese contemporary art scene. Record-breaking auction prices make good headlines, but they also confer a value on the artworks that few of their makers would have dreamed possible when those works were originally created— sometimes only a few years ago, in other cases a few decades. It is easy to understand the artists’ surprise at their flourishing market and media success: the secondary auction market for Chinese contemporary art emerged only recently, in 2005, when for the first time Christie’s held a designated Asian Contemporary Art sale in its annual Asian art auctions in Hong Kong. The auctions were a success, including the modern and contemporary sales, which brought in $18 million of the $90 million total; auction benchmarks were set for contemporary artists Zhang Huan, Yan Pei-Ming, Yue Minjun, and many others. The following year, Sotheby’s held its first dedicated Asian Contemporary sale in New York. -

Innovation Und Wandel Durch Chinas Heimgekehrte Akademiker?

Reverse Brain Drain: Innovation und Wandel durch Chinas heimgekehrte Akademiker? Eine Studie zum Einfluss geistes- und sozialwissenschaftlicher Rückkehrer am Beispiel chinesischer Eliteuniversitäten Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades der Doktorin der Philosophie an der Fakultät für Geisteswissenschaften der Universität Hamburg im Promotionsfach Sinologie vorgelegt von Birte Klemm Hamburg, 2017 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Michael Friedrich Zweitgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Yvonne Schulz Zinda Datum der Disputation: 14. August 2018 游学, 明时势,长志气,扩见闻,增才智, 非游历外国不为功也. 张之洞 1898 年《劝学篇·序》 Danksagung Ohne die Unterstützung einer Vielzahl von Menschen wäre diese Dissertation nicht zustande ge- kommen. Mein besonderer Dank gilt dem Betreuer dieser Arbeit, Prof. Dr. Michael Friedrich, für seine große Hilfe bei den empirischen Untersuchungen und die wertvollen Ratschläge bei der Erstellung der Arbeit. Für die Zweitbegutachtung möchte ich mich ganz herzlich bei Frau Prof. Dr. Yvonne Schulz Zinda bedanken. In der Konzeptionsphase des Projekts haben mich meine ehemaligen Kolleginnen und Kollegen am GIGA Institut für Asien-Studien, vor allem Prof. Dr. Thomas Kern, mit fachkundigen Ge- sprächen unterstützt. Ein großes Dankeschön geht überdies an Prof. Dr. Wang Weijiang und seine ganze Familie, an Prof. Dr. Chen Hongjie, Prof. Dr. Zhan Ru und Prof. Dr. Shen Wenzhong, die mir während meiner empirischen Datenerhebungen in Peking und Shanghai mit überwältigender Gastfreundschaft und Expertise tatkräftig zur Seite standen und viele Türen öffneten. An dieser Stelle möchte ich auch die zahlreichen Teilnehmerinnen und Teilnehmern der empiri- schen Umfragen dieser Studie würdigen. Hervorheben möchte ich die Studierenden der Beida und Fudan, die mir sehr bei der Verteilung der Fragebögen halfen und mir vielfältige Einblicke in das chinesische Hochschulwesen sowie studentische und universitäre Leben ermöglichten. -

Chinese Art Outside China Published by Edizioni Charta

Breakout: Chinese Art Outside China Published by Edizioni Charta. Milano, Italy, 2007 Jonathan Goodman ell conceived and well written, Melissa Chiu’s Breakout: Chinese Art Outside China Wconsiders the Chinese artistic diaspora— painters and sculptors, performance artists and conceptual practitioners who left the Mainland in favour of greater aesthetic freedom in America, Europe, and Australia. After the events on June 4, 1989, at Tian’anmen Square, the democracy movement in China was crushed, and many artists sought to escape what had become a prison house for the intelligentsia. At the same time, however, as Chiu points out in a perceptive introduction, there was a general exodus that had to do with cultural restlessness as much as political oppression. She finds that not everybody wanted to leave; she quotes Ah Xian, Cover of Breakout: Chinese Art Outside China. a ceramic artist who settled in Australia: “Once we had Image: Ah Xian, Human Human—Landscape 1, 00-00. Courtesy Edizioni Charta, Milano. the chance to go overseas, we tried as hard as we could to stay” . And most recently, many Chinese artists have returned to China, including such major figures as Zhang Huan, who never gave up his Chinese passport while working in America, and Xu Bing, who has accepted the post of vice president at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, where he received his Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees more than two decades ago. Chiu rightly suggests that the ebb and flow of immigration by Chinese artists is complicated, and much of her book, which is devoted to case studies of individual artists, claims a greater complexity for these figures than what the general perception might assert. -

Mao in Tibetan Disguise History, Ethnography, and Excess

2012 | HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 2 (1): 213–245 Mao in Tibetan disguise History, ethnography, and excess Carole MCGRANAHAN, University of Colorado What Does ethnographic theory look like in Dialogue with historical anthropology? Or, what Does that theory contribute to a Discussion of Tibetan images of Mao ZeDong? In this article, I present a renegaDe history told by a Tibetan in exile that Disguises Mao in Tibetan Dress as part of his journeys on the Long March in the 1930s. BeyonD assessing its histori- cal veracity, I consider the social truths, cultural logics, and political claims embeDDeD in this history as examples of the productive excesses inherent in anD generateD by conceptual Disjunctures. KeyworDs: History, Tibet, Mao, Disjuncture, excess In the back room of an antique store in Kathmandu, I heard an unusual story on a summer day in 1994. Narrated by Sherap, the Tibetan man in his 50s who owned the store, it was about when Mao Zedong came to Tibet as part of the communist Long March through China in the 1930s in retreat from advancing Kuomintang (KMT) troops.1 “Mao and Zhu [De],” he said, “were together on the Long March. They came from Yunnan through Lithang and Nyarong, anD then to a place calleD Dapo on the banks of a river, anD from there on to my hometown, Rombatsa. Rombatsa is the site of Dhargye Gonpa [monastery], which is known for always fighting with the Chinese. Many of the Chinese DieD of starvation, anD they haD only grass shoes to wear. Earlier, the Chinese haD DestroyeD lots of Tibetan monasteries. -

Artnet and the China Association of Auctioneers Global Chinese Antiques and Art Auction Market B Annual Statistical Report: 2012

GLOBAL CHINESE ANTIQUES AND ART AUCTION MARKET ANNUAL STATISTICAL REPORT 2012 artnet and the China Association of Auctioneers Global Chinese Antiques and Art Auction Market B Annual Statistical Report: 2012 Table of Contents ©2013 Artnet Worldwide Corporation. ©China Association of Auctioneers. All rights reserved. Letter from the China Association of Auctioneers (CAA) President ........... i About the China Association of Auctioneers (CAA) ................................. ii Letter from the artnet CEO .................................................................. iii About artnet ...................................................................................... iv 1. Market Overview ............................................................................. v 1.1 Industry Scale ............................................................................. 1 1.2 Market Scale ............................................................................. 3 1.3 Market Share ............................................................................. 5 2. Lot Composition and Price Distribution ........................................ 9 2.1 Lot Composition ....................................................................... 10 2.2 Price Distribution ...................................................................... 21 2.3 Average Auction Prices ............................................................. 24 2.4 High-Priced Lots ....................................................................... 27 3. Regional Analysis -

Art and China's Revolution

: january / february 9 January/February 2009 | Volume 8, Number 1 Inside Special Feature: The Phenomenon of Asian Biennials and Triennials Artist Features: Yang Shaobin, Li Yifan Art and the Cultural Revolution US$12.00 NT$350.00 6 VOLUME 8, NUMBER 1, JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2009 CONTENTS 2 Editor’s Note 32 4 Contributors Autumn 2008 Asian Biennials 6 Premature Farewell and Recycled Urbanism: Guangzhou Triennial and Shanghai Biennale in 2008 Hilary Tsiu 16 Post-West: Guangzhou Triennial, Taipei Biennial, and Singapore Biennale Jo-Anne Birnie Danzker Contemporary Asian Art and the Phenomenon of the Biennial 30 Introduction 54 Elsa Hsiang-chun Chen 32 Biennials and the Circulation of Contemporary Asian Art John Clark 41 Periodical Exhibitions in China: Diversity of Motivation and Format Britta Erickson 47 Who’s Speaking? Who’s Listening? The Post-colonial and the Transnational in Contestation and the Strategies of the Taipei Biennial and the Beijing International Art Biennale Kao Chien-hui 54 Contradictions, Violence, and Multiplicity in the Globalization of Culture: The Gwangju Biennale 78 Sohl Lee 61 The Imagined Trans-Asian Community and the Fukuoka Asian Art Triennale Elsa Hsiang-chun Chen Artist Features 67 Excerpts fom Yang Shaobin’s Notebook: A Textual Interpretation of X-Blind Spot Long March Writing Group 78 Li Yifan: From Social Archives to Social Project Bao Dong Art During the Cultural Revolution 94 84 Art and China’s Revolution Barbara Pollack 88 Zheng Shengtian and Hank Bull in Conversation about the Exhibition Art and China’s Revolution, Asia Society, New York 94 Red, Smooth, and Ethnically Unified: Ethnic Minorities in Propaganda Posters of the People’s Republic of China Micki McCoy Reviews 101 Chen Jiagang: The Great Third Front Jonathan Goodman 106 AAA Project: Review of A-Z, 26 Locations to Put Everything 101 Melissa Lam 109 Chinese Name Index Yuan Goang-Ming, Floating, 2000, single-channel video, 3 mins.