Irish Catholic Service and Identity in the British Armed Forces 1793-1815

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revolutionary Narratives, Imperial Rivalries: Britain and the French Empire in the Nineteenth Century

Revolutionary Narratives, Imperial Rivalries: Britain and the French Empire in the Nineteenth Century Author: Matthew William Heitzman Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:104076 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2013 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Boston College The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Department of English REVOLUTIONARY NARRATIVES, IMPERIAL RIVALRIES: BRITAIN AND THE FRENCH EMPIRE IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY A Dissertation by MATTHEW WILLIAM HEITZMAN submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2013 © copyright by MATTHEW WILLIAM HEITZMAN 2013 Revolutionary Narratives, Imperial Rivalries: Britain and the French Empire in the Nineteenth Century Author: Matthew William Heitzman Chair / AdVisor: Professor Rosemarie Bodenheimer Abstract: This dissertation considers England’s imperial riValry with France and its influence on literary production in the long nineteenth century. It offers a new context for the study of British imperialism by examining the ways in which mid- Victorian novels responded to and were shaped by the threat of French imperialism. It studies three canonical Victorian noVels: William Thackeray’s Vanity Fair (1846- 1848), Charlotte Brontë’s Villette (1853) and Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities (1859), and argues that even though these texts deal very lightly with the British colonies and feature Very few colonial figures, they are still Very much “about empire” because they are informed by British anxieties regarding French imperialism. Revolutionary Narratives links each noVel to a contemporary political crisis between England and France, and it argues that each novelist turns back to the Revolutionary period in response to and as a means to process a modern threat from France. -

PDF-Download

UNION DER EUROPÄISCHEN WEHRHISTORISCHEN GRUPPEN UNION OF THE EUROPEAN HISTORICAL MILITARY GROUPS Nr. 049 ZEITSCHRIFT - MAGAZINE Jahrgang 16 - 2020 Jahr der Herausforderungen Year of challenges FELDPOST | FIELD POST HOFARCHIV | COURT ARCHIVE Spanische Grippe und Corona Zauber der Montur: Kommando Spanish flu and Corona Magic of the Uniform: Command Seite 4 / page 4 Seite 18 / page 18 HOFARCHIV | COURT ARCHIVE TRUPPENDIENST | TROUPS SERVICE Militärpferdebedarf/Remontierung 12. Kaiserball Military horse supplies/remounting 12th Imperial Ball Seite 14 / page 14 Seite 23 / page 23 Nr. 049/2020 www.uewhg.eu 1 KOMMANDO - Vorwort Liebe Leserinnen und Leser, liebe Kameradinnen und Kameraden, Das heurige Jahr stellt uns alle vor große Heraus- seine Positionierung zum Schießsport für uns ein forderungen. Die Corona-Pandemie hat in fast je- Grund für diese Entscheidung. dem Lebensbereich ihre Spuren hinterlassen, auch wir in der Traditionspflege waren stark betroffen: Aber auch andere Themen der Traditionspflege haben uns in den letzten Monaten beschäftigt. In • Viele unserer Mitglieder gehören aufgrund ih- den letzten Jahren sind zwischen einigen Traditi- res fortgeschrittenen Alters zur Risikogruppe und onsvereinen und zwischen einigen Einzelpersonen gehören im Speziellen geschützt. Ich darf alle er- in diesen Vereinen die gegenseitige Beobachtung, muntern auch weiterhin trotz guter Entwicklung das gegenseitige Kritisieren und das Ausleben von in den meisten europäischen Ländern in der Aus- Befindlichkeiten stärker spürbar geworden. Uns breitung des Virus mit Bedacht und Vorsicht an allen in der Traditionspflege sollten ein paar Punk- Aktivitäten im Vereinsumfeld heranzugehen. te bewusst sein: • Fast alle unsere Veranstaltungen und Tref- • Einer seriösen Traditionspflege muss eine seriö- fen mussten abgesagt bzw. verschoben werden. se Tradition zugrunde liegen. -

THE BRITISH ARMY in the LOW COUNTRIES, 1793-1814 By

‘FAIRLY OUT-GENERALLED AND DISGRACEFULLY BEATEN’: THE BRITISH ARMY IN THE LOW COUNTRIES, 1793-1814 by ANDREW ROBERT LIMM A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY. University of Birmingham School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law October, 2014. University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The history of the British Army in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars is generally associated with stories of British military victory and the campaigns of the Duke of Wellington. An intrinsic aspect of the historiography is the argument that, following British defeat in the Low Countries in 1795, the Army was transformed by the military reforms of His Royal Highness, Frederick Duke of York. This thesis provides a critical appraisal of the reform process with reference to the organisation, structure, ethos and learning capabilities of the British Army and evaluates the impact of the reforms upon British military performance in the Low Countries, in the period 1793 to 1814, via a series of narrative reconstructions. This thesis directly challenges the transformation argument and provides a re-evaluation of British military competency in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. -

Defence Statistics 1999 21 DECEMBER 1999

RESEARCH PAPER 99/112 Defence Statistics 1999 21 DECEMBER 1999 The main aim of this paper, which updates Research Paper 98/120, is to bring together the more commonly used statistics relating to defence expenditure and manpower and to explain so of the problems involved in using such statistics, particularly when making international comparisons. Readers will also wish to consult a forthcoming Library Research Paper Defence Employment 1997-98 which sets out some statistics on defence employment and manpower. Bryn Morgan SOCIAL AND GENERAL STATISTICS SECTION HOUSE OF COMMONS LIBRARY Recent Library Research Papers include: 99/99 The Freedom of Information Bill: Data Protection Issues 03.12.99 [Bill 5 of 1999-2000] 99/100 The Electronic Communications Bill (revised edition) 08.12.99 [Bill 4 of 1999-2000] 99/101 The Terrorism Bill [Bill 10 of 1999-2000] 13.12.99 99/102 The Transport Bill: Part I National Air Traffic Services 13.12.99 [Bill 8 of 1999-2000] 99/103 The Transport Bill: Part II Local Transport Plans and Buses 13.12.99 [Bill 8 of 1999-2000] 99/104 The Transport Bill: Part III Road Charging and Workplace Parking 13.12.99 [Bill 8 of 1999-2000] 99/105 The Transport Bill: Part IV Railways [Bill 8 of 1999-2000] 13.12.99 99/106 Unemployment by Constituency – November 1999 15.12.99 99/107 The Millennium Trade Talks and the ‘Battle in Seattle’ 15.12.99 99/108 The Social Security, War Pension and National Insurance Provisions in 17.12.99 the Child Support, Pensions and Social Security Bill [Bill 9 of 1999-2000] 99/109 Pensions: Provisions -

Ancient, British and World Coins and Medals Auction 74 Wednesday 09 May 2012 10:00

Ancient, British and World Coins and Medals Auction 74 Wednesday 09 May 2012 10:00 Baldwin's Auctions 11 Adelphi Terrace London WC2N 6EZ Baldwin's Auctions (Ancient, British and World Coins and Medals Auction 74) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1001 Lot: 1005 ENGLISH COINS. Early Anglo ENGLISH COINS. Viking Saxon, Primary Sceattas (c.680- Coinage, Cnut, Penny, Cunetti c.710), Silver Sceat, BIIIA, type type, cross crosslet at centre, 27a, diademed head right with CNUT REX, rev short cross at protruding jaw, within serpent centre, pellets in first and third circle, rev linear bird on cross, quarters, within beaded circle, within serpent circle, annulets +CVN::NET::TI, 1.40g (N 501; S either side, pellets above beside 993). Well toned, one or two light bird, 0.87g (N 128; cf S 777B). marks, otherwise nearly Lightly toned, obverse die flaw, extremely fine otherwise well-struck, good very Estimate: £500.00 - £600.00 fine Estimate: £80.00 - £100.00 Lot: 1006 ENGLISH COINS. Viking Lot: 1002 Coinage of York, Danelaw (898- ENGLISH COINS. Early Anglo 915), Cnut, Patriarchal cross, C Saxon, Continental Sceattas N V T at cross ends, R E X in (c.695-c.740), Silver Sceatta, angles with pellets, rev small variety L, plumed bird right, cross, beaded circle around, annulet and pellet beside, rev +EBRAICE CIVITA.:, 1.45g (N standard with five annulets, each 497; S 991). Attractively toned, with central pellet, surmounting practically extremely fine. with old cross, 1.17g (cf N 49; S 791). Old pre-WWII Baldwin stock ticket cabinet tone, attractive extremely Estimate: £500.00 - £600.00 fine with clear and pleasing details Estimate: £80.00 - £100.00 Lot: 1007 ENGLISH COINS. -

Mons Memorial Museum Hosts Its First Temporary Exhibition, One Number, One Destiny

1 Press pack PRESS RELEASE From 13 June to 27 September 2015 , Mons Memorial Museum hosts its first temporary exhibition, One number, one destiny. Serving Napoleon . In a unique visitor experience , the exhibition offers a chance to relive the practice of conscription as used during the period of French rule from the Battle of Jemappes (1792) to the Battle of Waterloo (1815). This first temporary exhibition expresses the desire of the new military history museum of the City of Mons to focus on the visitor experience . The conventional setting of the chronological historical exhibition has been abandoned in favour of a far more personal immersion . The basic idea is to give visitors a sense of the huge impact of conscription on the lives of people at the time. With this in mind, each visitor will draw a number by lot to decide whether or not he or she has been ‘conscripted’, and so determine the route taken through the exhibition – either the section presenting the daily existence of conscripts recruited to serve under the French flag, or that focusing on life for the civilians who stayed at home . Visitors designated as conscripts will find out, through poignant letters, objects and other exhibits, about the lives of the soldiers – many of them ill-fated – as they made their way right across Europe in the fight against France’s enemies. Meanwhile, visitors in the other group will learn how those who stayed behind in Mons saw their daily lives turned upside-down by the numerous reforms introduced under the French, including the adoption of a new calendar, the eradication of references to religion, the acquisition of the right to vote, access to a new economic market and exposure to new cultural influences. -

TWICE a CITIZEN Celebrating a Century of Service by the Territorial Army in London

TWICE A CITIZEN Celebrating a century of service by the Territorial Army in London www.TA100.co.uk The Reserve Forces’ and Cadets’ Association for Greater London Twice a Citizen “Every Territorial is twice a citizen, once when he does his ordinary job and the second time when he dons his uniform and plays his part in defence.” This booklet has been produced as a souvenir of the celebrations for the Centenary of the Territorial Field Marshal William Joseph Slim, Army in London. It should be remembered that at the time of the formation of the Rifle Volunteers 1st Viscount Slim, KG, GCB, GCMG, GCVO, GBE, DSO, MC in 1859, there was no County of London, only the City. Surrey and Kent extended to the south bank of the Thames, Middlesex lay on the north bank and Essex bordered the City on the east. Consequently, units raised in what later became the County of London bore their old county names. Readers will learn that Londoners have much to be proud of in their long history of volunteer service to the nation in its hours of need. From the Boer War in South Africa and two World Wars to the various conflicts in more recent times in The Balkans, Iraq and Afghanistan, London Volunteers and Territorials have stood together and fought alongside their Regular comrades. Some have won Britain’s highest award for valour - the Victoria Cross - and countless others have won gallantry awards and many have made the ultimate sacrifice in serving their country. This booklet may be recognised as a tribute to all London Territorials who have served in the past, to those who are currently serving and to those who will no doubt serve in the years to come. -

The Family and Descendants of Sir Thomas More

The Family and Descendants of Sir Thomas More Grandparents: William More and Johanna Joye: William was a Citizen and Baker of London. He died in 1469. Johanna (d.1470) was the daughter of John Joye, a Citizen and Brewer of London and his wife Johanna, daughter of John Leycester, a Chancery Clerk. Due to the seizure of family documents by Henry VIII following Thomas More‟s execution his ancestry cannot be traced back further than this. He referred to himself as “a Londoner born, of no noble family, but of honest stock”. [Note: It has sometimes been claimed that Sir John More, Thomas More‟s father, said that his ancestors came from Ireland. However, what he actually said was that his ancestors “either came out of the Mores of Ireland, or they came out of us”. No records of any Irish links have been discovered.] Parents: Sir John More (c.1451-1530) and Agnes Graunger (d.1499): John and Agnes were married in the church of St Giles without Cripplegate, London, on 24th April 1474. Agnes was the daughter of Thomas Graunger, an Alderman of London and a Merchant of the Staple of Calais. Agnes was John More‟s first wife, and the mother of all his children. Agnes died in 1499 and was buried in the Church of St. Michael Bassishaw, London. After her death John More married again three times. His second wife was Joan Marshall (the widow of John Marshall) who died in 1505. His third wife was Joan Bowes (the widow of Thomas Bowes) who died in 1520. -

Marriage Certificates

GROOM LAST NAME GROOM FIRST NAME BRIDE LAST NAME BRIDE FIRST NAME DATE PLACE Abbott Calvin Smerdon Dalkey Irene Mae Davies 8/22/1926 Batavia Abbott George William Winslow Genevieve M. 4/6/1920Alabama Abbotte Consalato Debale Angeline 10/01/192 Batavia Abell John P. Gilfillaus(?) Eleanor Rose 6/4/1928South Byron Abrahamson Henry Paul Fullerton Juanita Blanche 10/1/1931 Batavia Abrams Albert Skye Berusha 4/17/1916Akron, Erie Co. Acheson Harry Queal Margaret Laura 7/21/1933Batavia Acheson Herbert Robert Mcarthy Lydia Elizabeth 8/22/1934 Batavia Acker Clarence Merton Lathrop Fannie Irene 3/23/1929East Bethany Acker George Joseph Fulbrook Dorothy Elizabeth 5/4/1935 Batavia Ackerman Charles Marshall Brumsted Isabel Sara 9/7/1917 Batavia Ackerson Elmer Schwartz Elizabeth M. 2/26/1908Le Roy Ackerson Glen D. Mills Marjorie E. 02/06/1913 Oakfield Ackerson Raymond George Sherman Eleanora E. Amelia 10/25/1927 Batavia Ackert Daniel H. Fisher Catherine M. 08/08/1916 Oakfield Ackley Irving Amos Reid Elizabeth Helen 03/17/1926 Le Roy Acquisto Paul V. Happ Elsie L. 8/27/1925Niagara Falls, Niagara Co. Acton Robert Edward Derr Faith Emma 6/14/1913Brockport, Monroe Co. Adamowicz Ian Kizewicz Joseta 5/14/1917Batavia Adams Charles F. Morton Blanche C. 4/30/1908Le Roy Adams Edward Vice Jane 4/20/1908Batavia Adams Edward Albert Considine Mary 4/6/1920Batavia Adams Elmer Burrows Elsie M. 6/6/1911East Pembroke Adams Frank Leslie Miller Myrtle M. 02/22/1922 Brockport, Monroe Co. Adams George Lester Rebman Florence Evelyn 10/21/1926 Corfu Adams John Benjamin Ford Ada Edith 5/19/1920Batavia Adams Joseph Lawrence Fulton Mary Isabel 5/21/1927Batavia Adams Lawrence Leonard Boyd Amy Lillian 03/02/1918 Le Roy Adams Newton B. -

Special Collections & Archives Service James Hardiman Library

Special Collections & Archives Service James Hardiman Library NUI, Galway 1 Contents Atlases & Maps 2-6 Biographical Sources 7-8 Bibliographical Sources 9-11 Dictionaries and Encyclopedias 12 Ireland – selected subject sources Art & Architecture 13 Archaeology 14-15 Local Studies 16 Emigration 17-18 Irish Ethnology & Folklore 19-20 Literary Research 21-22 Historical Research 23-26 Irish Family History 27-28 Newspapers 29-30 Official Publications 31 Theses & Dissertations 32 Periodicals & Rare Book Collections 33-35 Primary Sources Selected printed manuscript collections 36-38 James Hardiman Library Archives Microform, Microfiche & CD-ROM 39-45 Printed Manuscripts Guides & Indexes 46-48 Printed Manuscripts 49-52 Paper Archives 53-66 2 Atlases and Geographical Sources IRELAND Aalen, F.H.A. et al (eds). Atlas of the Irish Rural Landscape. Cork: Cork University Press, 1997. SCRR (& other locations) 911.415 ATL. Duffy, Sean. Atlas of Irish History. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan. 2000. SCRR 911.415 ATL Nolan, William & Simms, Annagret. Irish Towns: A guide to Sources. Dublin: Geography Publications, 1998. 307.76094515 IRI SCRR & Hum Ref. Royal Irish Academy. Historic Towns Atlas Series: all available in SCRR. Towns published so far: • No. 1 Kildare (1986) • No. 2 Carrickfergus (1986) • No. 3 Bandon (1988) • No. 4 Kells (1990) • No. 5 Mullingar (1992) • No. 6 Athlone (1994) • No. 7 Maynooth (1995) • No. 8 Downpatrick (1997) • No. 9 Bray (1998) • No. 10 Kilkenny (2000) • No. 11 Dublin, Part 1, to 1610 (2002) • No. 12 Belfast, Part 1, -

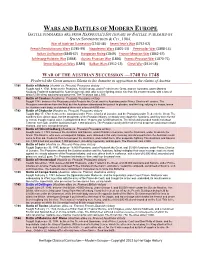

Wars and Battles of Modern Europe Battle Summaries Are from Harbottle's Dictionary of Battles, Published by Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1904

WARS AND BATTLES OF MODERN EUROPE BATTLE SUMMARIES ARE FROM HARBOTTLE'S DICTIONARY OF BATTLES, PUBLISHED BY SWAN SONNENSCHEIN & CO., 1904. War of Austrian Succession (1740-48) Seven Year's War (1752-62) French Revolutionary Wars (1785-99) Napoleonic Wars (1801-15) Peninsular War (1808-14) Italian Unification (1848-67) Hungarian Rising (1849) Franco-Mexican War (1862-67) Schleswig-Holstein War (1864) Austro Prussian War (1866) Franco Prussian War (1870-71) Servo-Bulgarian Wars (1885) Balkan Wars (1912-13) Great War (1914-18) WAR OF THE AUSTRIAN SUCCESSION —1740 TO 1748 Frederick the Great annexes Silesia to his domains in opposition to the claims of Austria 1741 Battle of Molwitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought April 8, 1741, between the Prussians, 30,000 strong, under Frederick the Great, and the Austrians, under Marshal Neuperg. Frederick surprised the Austrian general, and, after severe fighting, drove him from his entrenchments, with a loss of about 5,000 killed, wounded and prisoners. The Prussians lost 2,500. 1742 Battle of Czaslau (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought 1742, between the Prussians under Frederic the Great, and the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine. The Prussians were driven from the field, but the Austrians abandoned the pursuit to plunder, and the king, rallying his troops, broke the Austrian main body, and defeated them with a loss of 4,000 men. 1742 Battle of Chotusitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought May 17, 1742, between the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine, and the Prussians under Frederick the Great. The numbers were about equal, but the steadiness of the Prussian infantry eventually wore down the Austrians, and they were forced to retreat, though in good order, leaving behind them 18 guns and 12,000 prisoners. -

Most-Common-Surnames-Bmd-Registers-16.Pdf

Most Common Surnames Surnames occurring most often in Scotland's registers of Births, Marriages and Deaths Counting only the surname of the child for births, the surnames of BOTH PARTIES (for example both BRIDE and GROOM) for marriages, and the surname of the deceased for deaths Note: the surnames from these registers may not be representative of the surnames of the population of Scotland as a whole, as (a) they include the surnames of non-residents who were born / married / died here; (b) they exclude the surnames of residents who were born / married / died elsewhere; and (c) some age-groups have very low birth, marriage and death rates; others account for most births, marriages and deaths.ths Registration Year = 2016 Position Surname Number 1 SMITH 2056 2 BROWN 1435 3 WILSON 1354 4 CAMPBELL 1147 5 STEWART 1139 6 THOMSON 1127 7 ROBERTSON 1088 8 ANDERSON 1001 9 MACDONALD 808 10 TAYLOR 782 11 SCOTT 771 12 REID 755 13 MURRAY 754 14 CLARK 734 15 WATSON 642 16 ROSS 629 17 YOUNG 608 18 MITCHELL 601 19 WALKER 589 20= MORRISON 587 20= PATERSON 587 22 GRAHAM 569 23 HAMILTON 541 24 FRASER 529 25 MARTIN 528 26 GRAY 523 27 HENDERSON 522 28 KERR 521 29 MCDONALD 520 30 FERGUSON 513 31 MILLER 511 32 CAMERON 510 33= DAVIDSON 506 33= JOHNSTON 506 35 BELL 483 36 KELLY 478 37 DUNCAN 473 38 HUNTER 450 39 SIMPSON 438 40 MACLEOD 435 41 MACKENZIE 434 42 ALLAN 432 43 GRANT 429 44 WALLACE 401 45 BLACK 399 © Crown Copyright 2017 46 RUSSELL 394 47 JONES 392 48 MACKAY 372 49= MARSHALL 370 49= SUTHERLAND 370 51 WRIGHT 357 52 GIBSON 356 53 BURNS 353 54= KENNEDY 347