Lance Armstrong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WW1 CV for Randal S Gaulke Version November 2017

Curriculum Vitae Randal S. Gaulke Battlefield Tour Guide, Historian and Re-enactor 2017 Sabbatical in Doulcon, France • From 15 May to 15 November, 2017, Randal lived and worked as a Freelance tour guide to the American battlefields of WW1. • During this period he led numerous small-group tours; typically showing family members where their grandparents or parents fought. • He also participated in the filming of “A Golden Cross to Bear” (33rd Division, AEF) being produced by filmmaker Kane Farabaugh. o Viewing on various PBS stations in Illinois is planned for Memorial Day 2018. Previous Battlefield Tour Summary • Randal has visited the Western Front more than twenty times between 1986 and 2016. • Much of that time has been spent studying the Meuse-Argonne and St. Mihiel sectors. • Key tour summaries are listed below: --Verdun and Inf. Regt. Nr. 87 Tour, 2013 Randal spent three days leading an individual to the sites where his (German) great uncle fought, including the Verdun battlefield. --Western Front Association, USA Branch, 2007 Battlefield Tour Randal led the second half of the tour; focusing on the Meuse-Argonne and St. Mihiel Sectors. --8th Kuerassier (Reenacting) Regiment Trip to Germany and the Western Front, 2005 This was a five-day tour that followed in the regiment’s footsteps. --Verdun 1999 Tour Randal led participants on a two-day tour of the Verdun 1916 battlefield. --First Western Front Association, USA Branch, Battlefield Tour, 1998 The tour was organized by Tony and Teddy Noyes of UK-based Flanders Tours. Randal and Stephen Matthews provided significant input, US-based marketing, and logistical support to the effort. -

Armstrong.Pdf

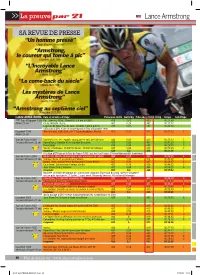

>> La preuve par 21 Lance Armstrong SA REVUE DE PRESSE “Un homme pressé” L’Equipe Magazine, 04.09.1993 “Armstrong, le coureur qui tombe à pic” L’Humanité, 05.07.1999 “L’Incroyable Lance Armstrong” L’Equipe, 12.07.1999 “Le come-back du siècle” L’Equipe, 26.07.1999 “Les mystères de Lance Armstrong” Le JDD, 27.06.2004 “Armstrong au septième ciel” Le Midi Libre, 25.07.2005 Lance ARMSTRONG Cols et victoires d’étape Puissance réelle watts/kg Puissance étalon 78 kg temps Cols Etape Tour Tour d’Espagne 1998 Pal. Jimenez 433w, 20min30s, 8,4 km à 6,49%, 418 5,65 400 00:21:49 4ème-27 ans Cerler. Montée courte. 462 6,24 442 00:11:33 Lagunas de Neila. Peu de vent, en forêt, 7 km à 8,57%, 415 5,61 397 00:22:18 Utilisation d’EPO et de cortisone durant le Tour d’Espagne 1998 Dauphiné 1999 Mont Ventoux CLM. ‘Battu de 1’1s par Vaughters. Record. 455 6,15 432 00:57:52 1 8ème-28 ans Tour de France 2004 La Mongie. 2ème derrière Basso 487 6,58 462 00:23:15 2 Tour de France 1999 Sestrières 1er. 1er «exploit» marquant en solo. Vent de face 448 6,05 420 00:27:13 5 1er puis déclassé-33 ans Beille 1er. En solitaire. 438 5,92 416 00:45:40 6 1er puis déclassé-28 ans Alpe d’Huez. Contrôle et se contente de suivre. 436 5,89 407 00:41:20 3 Chalimont 1er. Victoire à Villard de Lans 410 5,54 392 00:19:05 3 Piau Engaly 395 5,34 385 00:26:15 5 Alpe d’Huez CLM 1er. -

Lance Armstrong Has Something to Get Off His Chest

Texas Monthly July 2001: Lanr^ Armstrong Has Something to . Page 1 of 17 This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. For public distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers, contact [email protected] for reprint information and fees. (EJiiPfflNITHIS Lance Armstrong Has Something to Get Off His Chest He doesn't use performance-enhancing drugs, he insists, no matter what his critics in the European press and elsewhere say. And yet the accusations keep coming. How much scrutiny can the two-time Tour de France winner stand? by Michael Hall In May of last year, Lance Armstrong was riding in the Pyrenees, preparing for the upcoming Tour de France. He had just completed the seven-and-a-half-mile ride up Hautacam, a treacherous mountain that rises 4,978 feet above the French countryside. It was 36 degrees and raining, and his team's director, Johan Bruyneel, was waiting with a jacket and a ride back to the training camp. But Lance wasn't ready to go. "It was one of those moments in my life I'll never forget," he told me. "Just the two of us. I said, 'You know what, I don't think I got it. I don't understand it.1 Johan said, 'What do you mean? Of course you got it. Let's go.' I said, 'No, I'm gonna ride all the way down, and I'm gonna do it again.' He was speechless. And I did it again." Lance got it; he understood Hautacam—in a way that would soon become very clear. -

The Podium for Holland, the Plush Bench for Belgium

The Podium for Holland, The Plush Bench for Belgium The Low Countries and the Olympic Games 58 [ h a n s v a n d e w e g h e ] Dutch Inge de Bruin wins The Netherlands is certain to win its hundredth gold medal at the London 2012 gold. Freestyle, 50m. Olympics. Whether the Belgians will be able to celebrate winning gold medal Athens, 2004. number 43 remains to be seen, but that is not Belgium’s core business: Bel- gium has the distinction of being the only country to have provided two presi- dents of the International Olympic Committee. The Netherlands initially did better in the IOC membership competition, too. Baron Fritz van Tuijll van Serooskerken was the first IOC representative from the Low Countries, though he was not a member right from the start; this Dutch nobleman joined the International Olympic Committee in 1898, two years after its formation, to become the first Dutch IOC member. Baron Van Tuijll is still a great name in Dutch sporting history; in 1912 he founded a Dutch branch of the Olympic Movement and became its first president. However, it was not long before Belgium caught up. There were no Belgians among the 13 men – even today, women members are still few and far between – who made up the first International Olympic Committee in 1894, but thanks to the efforts of Count Henri de Baillet-Latour, who joined the IOC in 1903, the Olympic Movement became the key international point of reference for sport in the Catholic south. The Belgian Olympic Committee was formed three years later – a year af- ter Belgium, thanks to the efforts of King Leopold II, had played host to the prestigious Olympic Congress. -

Introduction to the Introduction to the Teams

INTRODUCTION TO THE TEAMS AND RIDERS TO WATCH FOR GarminGarmin----TransitionsTransitions Ryder Hesjedal, 7th overall in the Tour de France, and the first Canadian Top 10 finisher in the Grande Boucle since Steve Bauer in 1988, will be looking to shine in front of the home crowd. EuskaltelEuskaltel----EuskadiEuskadi This team is made up almost entirely of cyclists from the Basque Country. Samuel Sánchez, Gold Medalist at the Beijing Olympics, narrowly missed the podium in this year’s Tour de France. Rabobank The orange-garbed team brings a 100% Dutch line-up to Québec and Montréal, led by Robert Gesink, a 24-year-old full of promise who finished 6th overall in the 2010 Tour de France, and solid lieutenants like Joost PosthumaPosthuma and Bram Tankink. Team RadioShack Lance Armstrong’s team fields a strong entry, featuring the backbone of the squad that competed in the Tour de France, including Levi Leipheimer (USA), 3rd overall in the 2007 Tour and Bronze Medalist in the Individual Time Trial in Beijing, Janez Brajkovic (Slovenia), winner of the 2010 Critérium du Dauphiné, and Sergio Paulinho (Portugal), who won a stage in this year’s Tour de France and was a Silver Medalist in Athens in 2004 and Yaroslav Popovych (Ukraine), former top 3 on the Tour of Italy. LiquigasLiquigas----DoimoDoimo This Italian squad will be counting on Ivan Basso, who won this year’s Giro d’Italia but faded in the Tour de France, but also on this past spring’s sensation, 20-year-old Peter Sagan of Slovakia, who won two stages of the Paris-Nice race, two in the Tour of California and one in the Tour de Romandie. -

Book JAVNOST 4-2013.Indb

“BRAND CHINA” IN THE OLYMPIC CONTEXT COMMUNICATIONS CHALLENGES OF CHINA’S SOFT POWER INITIATIVE SUSAN BROWNELL 82 - Abstract The Beijing 2008 Olympics were widely considered to be Susan Brownell is Professor China’s moment for improving its national image worldwide. of Anthropology in the However, the consensus both inside and outside China was Department of Anthropology, that although the Olympics succeeded in advancing an Sociology, and Languages, image of an emerging powerful, prosperous, and well-or- University of Missouri-St. Louis; ganised nation, the message was hijacked by interest groups e-mail: [email protected]. critical of government policies on human rights and Tibet, who were more successful in putting forward their positions in the international media than the Chinese government was. The article analyses the communications challenges that created obstacles for genuine dialogue on sensi- Vol.20 (2013), No. 4, pp. 65 4, pp. (2013), No. Vol.20 tive issues. In its post-Olympics assessment, the Chinese government acknowledged the weakness of China’s voice in international (especially Western) media and responded with a planned US$6 billion investment for strengthening its foreign communications capacity as part of its “soft power” initiative (fi rst called for by President Hu Jintao in 2007). 65 For the eight years from the time that Beijing announced its bid for the 2008 Olympic Games until the conclusion of the games, observers both inside and out- side China widely considered the Beijing 2008 Olympics to be China’s moment for improving its national image worldwide. Beneath this att ention to “national image” lay a power struggle. -

Pedalare! Pdf, Epub, Ebook

PEDALARE! PEDALARE! PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John Foot | 384 pages | 22 Jun 2012 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781408822197 | English | London, United Kingdom Pedalare! Pedalare! by John Foot - Podium Cafe This website uses cookies to improve user experience. By using our website you consent to all cookies in accordance with our Cookie Policy. It looks like you are located in Australia or New Zealand Close. Visit the Australia site Continue on UK site. Visit the Australia site. Continue on UK site. Cycling was a sport so important in Italy that it marked a generation, sparked fears of civil war, changed the way Italian was spoken, led to legal reform and even prompted the Pope himself to praise a cyclist, by name, from his balcony in St Peter's in Rome. It was a sport so popular that it created the geography of Italy in the minds of her citizens, and some have said that it was cycling, not political change, that united Italy. The book moves chronologically from the first Giro d'Italia Italy's equivalent of the Tour de France in to the present day. The tragedies and triumphs of great riders such as Fausto Coppi and Gino Bartali appear alongside stories of the support riders, snow-bound mountains and the first and only woman to ride the whole Giro. Cycling's relationship with Italian history, politics and culture is always up front, with reference to fascism, the cold war and the effect of two world wars. Cycling's relationship with Italian history, politics and culture is always up front, with reference to fascism, the cold war and the effect of two world wars. -

Spitting in the Soup Mark Johnson

SPITTING IN THE SOUP INSIDE THE DIRTY GAME OF DOPING IN SPORTS MARK JOHNSON Copyright © 2016 by Mark Johnson All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic or photocopy or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations within critical articles and reviews. 3002 Sterling Circle, Suite 100 Boulder, Colorado 80301-2338 USA (303) 440-0601 · Fax (303) 444-6788 · E-mail [email protected] Distributed in the United States and Canada by Ingram Publisher Services A Cataloging-in-Publication record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN 978-1-937715-27-4 For information on purchasing VeloPress books, please call (800) 811-4210, ext. 2138, or visit www.velopress.com. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). Art direction by Vicki Hopewell Cover: design by Andy Omel; concept by Mike Reisel; illustration by Jean-Francois Podevin Text set in Gotham and Melior 16 17 18 / 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Introduction ...................................... 1 1 The Origins of Doping ............................ 7 2 Pierre de Coubertin and the Fair-Play Myth ...... 27 3 The Fall of Coubertin’s Ideal ..................... 41 4 The Hot Roman Day When Doping Became Bad ..................................... 55 5 Doping Becomes a Crime........................ 75 6 The Birth of the World Anti-Doping Agency ..... 85 7 Doping and the Cold War........................ 97 8 Anabolic Steroids: Sports as Sputnik .......... -

Play True! the Slogan "Play True" Has Been Chosen to Incarnate the Principal Values of WADA

No.1 The official newsletter of the World Anti-Doping Agency – February 2002 Play true! The slogan "play true" has been chosen to incarnate the principal values of WADA. It stands for the universal spirit of sports practiced without artifice and in full respect of the established rules. All over the world, WADA’s members, staff and consultants are performing their duties with this slogan in mind. They practice these values on a daily basis, whether it is in the framework of the major undertaking of preparing the World Anti-Doping Code, out-of-competition testing, the awareness programmes or any of the other areas of the activities described in this newsletter. Henceforth, "WADA news", is to become a regular highlight giving you the opportunity to learn more about the life, the achievements and the projects of WADA. Moreover, since the athletes, the International Fe d e r ations and the countries are themselves WAD A ’ s Mr Richard W.Pound, Q.C., WADA Chairman stakeholders, the newsletter is also largely devoted to their concerns. Very soon the Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games will be beginning in Salt Lake City. Naturally WADA will be present and everyone will be able to measure the extent of WADA’s achievements since Sydney and Inside: as well as its first steps in the arena of the world’s great international sports events. Editorial: Play true! 1 All the work accomplished in the last two years has WADA in brief 2 been made possible by the essential support of the Glossary 3 International Olympic Committee, which we wish to Doping control 4 thank here. -

Sunday Independent

10 SPORT SOCCER / CYCLING Sunday Independent 22 March 2015 Ronaldo out to swing Determined to the balance back his way See-sawing battle for supremacy with Messi be his own man comes to a head in Clasico, says Sid Lowe CRISTIANO RONALDO laid down the Ballon d’Or on the plinth in front of him and began his acceptance speech, Sepp in the peloton Blatter to the left of him, Thierry Henry to the right. As he drew to a close, he thanked everyone and then paused. He leant in towards the microphone, clenched his fists and boomed out a long, deep “Si”. This was Ronaldo’s third Bal- lon d’Or but he was determined and off the bike it would not be his last. Only one player has won more and he was sitting in the front row, a runner-up: Lionel Messi. Before the presentation, the two footballers had met briefly. Ronaldo called Messi over to meet his son, telling the Argentinian that Ronaldo junior watched him on Nicolas Roche, his sister television, talked about him. He Christel and their mother also admitted that Messi’s success Lydia: ‘I always felt I was in helped to drive him. “I’m sure the the middle; when I was in competition between us motivates Ireland I was ‘the foreigner’, him too. It’s good for me, good for and when I was in France I him and good for other players who PAUL KIMMAGE was ‘the foreigner’, and I’m want to grow,” he said. meets attached to both sides, but For four years, Ronaldo had there’s a little thing that finished second to Messi but he had NICOLAS ROCHE makes me feel that bit more not given up. -

Momentos Ciclistas Textos Del Blog Ciclismo De Verdad

Momentos ciclistas Textos del blog Ciclismo de Verdad Textos del blog http://ciclismodeverdad.wordpress.com/ https://twitter.com/ciclismoverdad https://www.facebook.com/ciclismo.deverdad [CDV] El número 1 5 diciembre, 2013 No existe posible discusión. Hay que ser muy bueno para liderar el ranking UCI en el bienio demoledor del Sky. Joaquín Rodríguez lo ha logrado pese a no contar, ni de lejos, con el potencial deportivo y financiero de los ingleses. Pudo el año pasado, en puntos UCI, con un exuberante Wiggins, capaz de controlar la París Niza, Romandía, Dauphiné, Tour y la crono de las Olimpiadas. Eso son palabras mayores. El de Katusha se retorció en el Giro para terminar segundo tras arrinconar a Hesjedal y, en la Vuelta, sólo la última genialidad de Contador le descolocó a él y a su equipo. Por el camino, en cambio, sí cayeron la Flecha y Lombardía en un ejercicio sublime éste último. Esta temporada, Froome ha hecho de Wiggins en una repetición malsana de las fórmulas del gurú Tim Kerrison en el Sky. Y, de nuevo, Rodríguez ha vencido, en puntos UCI, claro, porque más allá es complicado. Sólo el error de cálculo de los Sky al final de año ha permitido a ‘Purito’ volver a reinar. No les funcionó a los hombres de negro la vuelta a la competición después del descanso del Tour. Froome y Porte se fueron a EE.UU para concentrarse, como habían hecho meses antes en el Teide, y competir en el USA Pro Challenge, en Canadá y preparar el Mundial y Lombardía. No alcanzaron su mejor nivel, lo que aprovechó el de Katusha para brillar en el Mundial, pese a la torpeza de Valverde, y en Lombardía. -

November 2016 Contents

November 2016 Track and Field Contents Writers of P. 1 President’s Message America P. 3 TAFWA Notes (Founded June 7, 1973) P. 4 2017 TAFWA Awards P. 5 While Much Has Been Gained ... PRESIDENT P. 6 Russian Sport Undergoes a Penance-Free Purge Jack Pfeifer 216 Ft. Washington Ave., P. 7 Exclusive: Anger as Rio 2016 Fail to Pay Staff and Companies Because NY, NY 10032 of Finanacial Crisis Office/home: 917-579- P. 8 ‘Rejuvenated’ Mary Cain Explains Coaching Change 5392. Email: P. 10 Windfall Productions Renews ESPN Collegiate Track & Field [email protected] P. 11 Five Questions on the Farm VICE PRESIDENT P. 13 USA Track & Field CEO Has Alarmed Some Insiders With His Spending & Style Doug Binder P. 19 Keshorn, TT Athletes Discuss Problems in the Sport Email: P. 20 42 Russian Athletes to Get Compensation for Missing Rio 2016 Olympics [email protected]. Phone: 503-913-4191 P. 21 Runners Reunited Welcomes a Big First 1956 Olympian Don Bowden P. 24 Russian Rage Over Doping Points to a New Cold War TREASURER P. 26 Russian Hackers Draw Attention to Drug-Use Exemptions for Athletes Tom Casacky P. 28 Goldie Sayers and GB’s 4x400m Relay Team Upgraded to 2008 Bronze P.O. Box 4288 Napa, CA 94558 P. 28 Mark Emmert: NCAA Might Reconsider Olympic Bonuses for Athletes Phone: 818-321-3234 P. 29 Tokyo 1940: A Look Back at the Olympic Games That Never Happened Email: [email protected] P. 32 Charlotte Loses NAIA Cross Country Championships over House Bill 2 P. 32 Christian Schools Nix NAIA Boycott SECRETARY Jon Hendershott P.