The Podium for Holland, the Plush Bench for Belgium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2004 Olympic Trials Results

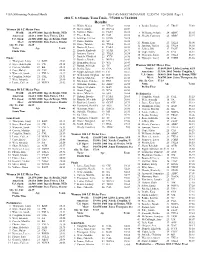

USA Swimming-National Meets Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 12:55 PM 1/26/2005 Page 1 2004 U. S. Olympic Team Trials - 7/7/2004 to 7/14/2004 Results 13 Walsh, Mason 19 VTAC 26.08 8 Benko, Lindsay 27 TROJ 55.69 Women 50 LC Meter Free 15 Silver, Emily 18 NOVA 26.09 World: 24.13W 2000 Inge de Bruijn, NED 16 Vollmer, Dana 16 FAST 26.12 9 Williams, Stefanie 24 ABSC 55.95 American: 24.63A 2000 Dara Torres, USA 17 Price, Keiko 25 CAL 26.16 10 Shealy, Courtney 26 ABSC 55.97 18 Jennings, Emilee 15 KING 26.18 U.S. Open: 24.50O 2000 Inge de Bruijn, NED 19 Radke, Katrina 33 SC 26.22 Meet: 24.90M 2000 Dara Torres, Stanfor 11 Phenix, Erin 23 TXLA 56.00 20 Stone, Tammie 28 TXLA 26.23 Oly. Tr. Cut: 26.39 12 Jamison, Tanica 22 TXLA 56.02 21 Boutwell, Lacey 21 PASA 26.29 Name Age Team 13 Jeffrey, Rhi 17 FAST 56.09 22 Harada, Kimberly 23 STAR 26.33 Finals Time 14 Cope, Haley 25 CAJ 56.11 23 Jamison, Tanica 22 TXLA 26.34 15 Wanezek, Sarah 21 TXLA 56.19 24 Daniels, Elizabeth 22 JCCS 26.36 Finals 16 Nymeyer, Lacey 18 FORD 56.56 25 Boncher, Brooke 21 NOVA 26.42 1 Thompson, Jenny 31 BAD 25.02 26 Hernandez, Sarah 19 WA 26.43 2 Joyce, Kara Lynn 18 CW 25.11 27 Bastak, Ashleigh 22 TC 26.47 Women 100 LC Meter Free 3 Correia, Maritza 22 BA 25.15 28 Denby, Kara 18 CSA 26.50 World: 53.66W 2004 Libby Lenton, AUS 4 Cope, Haley 25 CAJ 25.22 29 Ripple Johnston, Shell 23 ES 26.51 American: 53.99A 2002 Natalie Coughlin, U 5 Wanezek, Sarah 21 TXLA 25.27 29 Medendorp, Meghan 22 IST 26.51 U.S. -

Book JAVNOST 4-2013.Indb

“BRAND CHINA” IN THE OLYMPIC CONTEXT COMMUNICATIONS CHALLENGES OF CHINA’S SOFT POWER INITIATIVE SUSAN BROWNELL 82 - Abstract The Beijing 2008 Olympics were widely considered to be Susan Brownell is Professor China’s moment for improving its national image worldwide. of Anthropology in the However, the consensus both inside and outside China was Department of Anthropology, that although the Olympics succeeded in advancing an Sociology, and Languages, image of an emerging powerful, prosperous, and well-or- University of Missouri-St. Louis; ganised nation, the message was hijacked by interest groups e-mail: [email protected]. critical of government policies on human rights and Tibet, who were more successful in putting forward their positions in the international media than the Chinese government was. The article analyses the communications challenges that created obstacles for genuine dialogue on sensi- Vol.20 (2013), No. 4, pp. 65 4, pp. (2013), No. Vol.20 tive issues. In its post-Olympics assessment, the Chinese government acknowledged the weakness of China’s voice in international (especially Western) media and responded with a planned US$6 billion investment for strengthening its foreign communications capacity as part of its “soft power” initiative (fi rst called for by President Hu Jintao in 2007). 65 For the eight years from the time that Beijing announced its bid for the 2008 Olympic Games until the conclusion of the games, observers both inside and out- side China widely considered the Beijing 2008 Olympics to be China’s moment for improving its national image worldwide. Beneath this att ention to “national image” lay a power struggle. -

KNZB NK 2007 01 Juni 2007,18:35 Nationale Kampioenschappen Zwemmen 2007 Ranglijst Bladzijde 2 Nr. 1 400M Vrije Slag

Nationale Kampioenschappen Zwemmen 2007 Bladzijde 2 Ranglijst Nr. 1 400m vrije slag Heren Heren Senioren Open 01.06.2007 Limiet 4:31.00 Wereldrecord 2002 3:40.08 Ian Thorpe AUS Manchester Europees Record 2000 3:43.40 Massimiliano Rosolino ITA Sydney Nationaal Record 2002 3:47.20 Pieter van den Hoogenband NED Amersfoort Kampioenschapsrecord 2002 3:47.20 Pieter van den Hoogenband PSV Amersfoort Heren Jeugd 1 en 2 Jr. Afk./depot Tijd RT 1. Job Kienhuis 89 De Dinkel Denek 4:03.87 0.93 50m: 28.48 28.48 150m: 1:30.00 30.36 250m: 2:31.45 30.44 350m: 3:33.22 30.89 100m: 59.64 31.16 200m: 2:01.01 31.01 300m: 3:02.33 30.88 400m: 4:03.87 30.65 2. Jorrit Visser 89 DZ&PC 4:12.25 50m: 28.34 28.34 150m: 1:31.78 32.24 250m: 2:37.09 32.84 350m: 3:42.50 32.77 100m: 59.54 31.20 200m: 2:04.25 32.47 300m: 3:09.73 32.64 400m: 4:12.25 29.75 3. Bo Wullings 89 De Dolfijn 4:12.37 50m: 27.92 27.92 150m: 1:29.33 31.04 250m: 2:34.69 33.18 350m: 3:41.38 33.23 100m: 58.29 30.37 200m: 2:01.51 32.18 300m: 3:08.15 33.46 400m: 4:12.37 30.99 4. Ewoud Potiek 89 't Tolhekke 4:15.10 50m: 28.22 28.22 150m: 1:33.58 33.25 250m: 2:39.68 32.66 350m: 3:44.35 32.11 100m: 1:00.33 32.11 200m: 2:07.02 33.44 300m: 3:12.24 32.56 400m: 4:15.10 30.75 5. -

Amsterdam Swim Cup 2015 Amsterdam, 11 - 13 December 2015

Amsterdam Swim Cup 2015 Amsterdam, 11 - 13 December 2015 Event 17 Women, 100m Butterfly Senioren Open 12-12-2015 - 10:16 Startlist Prelim World Record 55.64 Sarah Sjöström Kazan (RUS) 03-08-2015 European Record 55.64 Sarah Sjöström Kazan (RUS) 03-08-2015 Nederlands Record Senioren 56.61 Inge de Bruijn Sydney (AUS) 17-09-2000 Nederlands Record Jeugd 1:01.20 Chantal Groot Antwerpen (BEL) 02-08-1998 Nederlands Record Junioren 1:02.90 Nathalie Koekkoek West-Berlijn (FRG) 26-07-1986 Sloterparkbad Record 56.69 Marleen Veldhuis Amsterdam 17-04-2009 Limieten OS Rio 2016 58.19 Richttijden EK 2016 Londen 58.70 Kwalificatietijd EJK2016 1999 1:00.49 Kwalificatietijd EJK2016 2000 1:02.02 Kwalificatietijd EJK2016 2001-2002 1:02.20 Kwalificatietijd vEYOF 2016 1:04.69 name club name entry time Heat 1 of 6 1 Kristel Hormann TriVia 1:09.34 199601084 2 Danieke van der Kooi Orca 1:08.64 200000552 3 Johanne Heines Pettersen Sandnes Svømme 1:07.82 4 Marije Dinkelberg SCOM/De Zeehond'73 (SG) 1:06.56 199703192 5 Renee Vanderheyden ReVeLie Swim Team 1:07.42 199903130 6 Brenda Zwarthoed DAW 1:08.00 199604938 7 Ina Willigers Zwemclub Eijsden 1:09.03 199702678 8 Kristy Nagtzaam ZC AquaDream 1:09.41 200002212 Heat 2 of 6 1 Lara Butler Loughborough University 1:05.69 928679 2 Jasmijn Boon WVZ 1:05.06 200001280 3 Alma Thormalm Jönköpings SS 1:05.02 4 Chefanja Nunes WVZ 1:04.93 200104750 5 Juliette Dumont FFBN 1:04.93 6 Elise Tanis RTC-De Schoteijl 1:05.06 200200120 7 Leonie Goebels SG Essen 1:05.68 258828 8 Antonia Massone SSG Saar Max Ritter 1:05.82 187244 Heat 3 of 6 1 Line Loevberg Lambertseter SK 1:04.62 2 Julia Schnorrbusch SGS Hamburg 1:03.56 181678 3 Irene Garcia De Dios Leyva C.N. -

Play True! the Slogan "Play True" Has Been Chosen to Incarnate the Principal Values of WADA

No.1 The official newsletter of the World Anti-Doping Agency – February 2002 Play true! The slogan "play true" has been chosen to incarnate the principal values of WADA. It stands for the universal spirit of sports practiced without artifice and in full respect of the established rules. All over the world, WADA’s members, staff and consultants are performing their duties with this slogan in mind. They practice these values on a daily basis, whether it is in the framework of the major undertaking of preparing the World Anti-Doping Code, out-of-competition testing, the awareness programmes or any of the other areas of the activities described in this newsletter. Henceforth, "WADA news", is to become a regular highlight giving you the opportunity to learn more about the life, the achievements and the projects of WADA. Moreover, since the athletes, the International Fe d e r ations and the countries are themselves WAD A ’ s Mr Richard W.Pound, Q.C., WADA Chairman stakeholders, the newsletter is also largely devoted to their concerns. Very soon the Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games will be beginning in Salt Lake City. Naturally WADA will be present and everyone will be able to measure the extent of WADA’s achievements since Sydney and Inside: as well as its first steps in the arena of the world’s great international sports events. Editorial: Play true! 1 All the work accomplished in the last two years has WADA in brief 2 been made possible by the essential support of the Glossary 3 International Olympic Committee, which we wish to Doping control 4 thank here. -

Welcome to the Issue

Welcome to the issue Volker Kluge Editor It is four years since we decided to produce the Journal triple jump became the “Brazilian” discipline. History of Olympic History in colour. Today it is scarcely possible and actuality at the same time: Toby Rider has written to imagine it otherwise. The pleasing development of about the first, though unsuccessful, attempt to create ISOH is reflected in the Journal which is now sent to 206 an Olympic team of refugees, and Erik Eggers, who countries. accompanied Brazil’s women’s handball team, dares to That is especially thanks to our authors and the small look ahead. team which takes pains to ensure that this publication Two years ago Myles Garcia researched the fate of can appear. As editor I would like to give heartfelt the Winter Olympic cauldrons. In this edition he turns thanks to all involved. his attention to the Summer Games. Others have also It is obvious that the new edition is heavily influenced contributed to this piece. by the Olympic Games in Rio. Anyone who previously Again there are some anniversaries. Eighty years ago believed that Brazilian sports history can be reduced the Games of the XI Olympiad took place in Berlin, to to football will have to think again. The Olympic line of which the Dutch water polo player Hans Maier looks ancestry begins as early as 1905, when the IOC presented back with mixed feelings. The centenarian is one of the the flight pioneer Alberto Santos-Dumont with one of few surviving participants. the first four Olympic Diplomas. -

November 2016 Contents

November 2016 Track and Field Contents Writers of P. 1 President’s Message America P. 3 TAFWA Notes (Founded June 7, 1973) P. 4 2017 TAFWA Awards P. 5 While Much Has Been Gained ... PRESIDENT P. 6 Russian Sport Undergoes a Penance-Free Purge Jack Pfeifer 216 Ft. Washington Ave., P. 7 Exclusive: Anger as Rio 2016 Fail to Pay Staff and Companies Because NY, NY 10032 of Finanacial Crisis Office/home: 917-579- P. 8 ‘Rejuvenated’ Mary Cain Explains Coaching Change 5392. Email: P. 10 Windfall Productions Renews ESPN Collegiate Track & Field [email protected] P. 11 Five Questions on the Farm VICE PRESIDENT P. 13 USA Track & Field CEO Has Alarmed Some Insiders With His Spending & Style Doug Binder P. 19 Keshorn, TT Athletes Discuss Problems in the Sport Email: P. 20 42 Russian Athletes to Get Compensation for Missing Rio 2016 Olympics [email protected]. Phone: 503-913-4191 P. 21 Runners Reunited Welcomes a Big First 1956 Olympian Don Bowden P. 24 Russian Rage Over Doping Points to a New Cold War TREASURER P. 26 Russian Hackers Draw Attention to Drug-Use Exemptions for Athletes Tom Casacky P. 28 Goldie Sayers and GB’s 4x400m Relay Team Upgraded to 2008 Bronze P.O. Box 4288 Napa, CA 94558 P. 28 Mark Emmert: NCAA Might Reconsider Olympic Bonuses for Athletes Phone: 818-321-3234 P. 29 Tokyo 1940: A Look Back at the Olympic Games That Never Happened Email: [email protected] P. 32 Charlotte Loses NAIA Cross Country Championships over House Bill 2 P. 32 Christian Schools Nix NAIA Boycott SECRETARY Jon Hendershott P. -

Netherlands Hsl Zuid

HSL ZUID, AMSTERDAM-ROTTERDAM(-ANTWERP), THE NETHERLANDS(-BELGIUM) OVERVIEW INTRODUCTION LOCATION: AMSTERDAM-ROTTERDAM -ANTWERP HSL Zuid is a high speed rail line, SCOPE: TRANSNATIONAL 125km long, stopping at three TRANSPORT MODE: RAIL stations: Amsterdam Zuid, PRINCIPAL CONSTRUCTION: GRADE Amsterdam Schiphol Airport and NEW LINK: YES Rotterdam, before continuing to the PRINCIPAL OBJECTIVES Dutch/Belgian border to connect NATIONAL/INTERNATIONAL LINK with services to Antwerp, Brussels ALTERNATIVE TO AIR TRAVEL and Paris. The Hague and Breda are ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT linked to the high speed network by PRINCIPAL STAKEHOLDERS shuttle trains. CLIENT: NATIONAL TRANSPORT MINISTRY FUNDER: NATIONAL GOVERNMENT Amsterdam Zuid has been the site of major redevelopment and is MAIN CONTRACTOR: INFRASPEED now a prominent business district. HSL-Zuid has also been a catalyst OPERATOR: NS HISPEED for the ongoing extensive redevelopment of Amsterdam Central PLANNING AND IMPLEMENTATION (where the line originally terminated, before Zuid station opened), APPROX. PLANNING START DATE: 1987 Rotterdam Central, The Hague Central and Breda stations. CONSTRUCTION START DATE: 03/2000 OPERATION START DATE: 09/2009 BACKGROUND MONTHS IN PLANNING: 153 MONTHS IN CONSTRUCTION: 114 PROJECT COMPLETED: The principal objectives of the project were to connect Rotterdam, 48 MONTHS BEHIND SCHEDULE Schiphol and Amsterdam to the European High Speed Network, to COSTS (IN 2010 USD) encourage economic development, and to provide an alternative to air travel to European destinations. It was anticipated in the PREDICTED COST: 6.87BN government’s 1979 structure scheme and a 1986 feasibility study, ACTUAL COST: 9.79BN PROJECT COMPLETED: although the formal planning process started only in 1987. 42% OVER BUDGET FUNDING: 86% PUBLIC : 14% PRIVATE The initial proposal was withdrawn as it was felt to be weak, but the revised version already included environmental impact assessments and public consultation from the first. -

2020 U.S. Olympic Team Trials - Swimming 1 Media Guidelines & Information Usaswimming.Org/Trials L @Usaswimming L @Usaswimmingnews L #Swimtrials21

2020 U.S. Olympic Team Trials - Swimming 1 Media Guidelines & Information usaswimming.org/trials l @USASwimming l @USASwimmingNews l #SwimTrials21 Facility Address Media Seating CHI Health Center Omaha USA Swimming will provide seating charts for tabled media in the competition 455 N. 10th Street venue. Overflow (non-tabled) media seating is available in section 102 and 103. Omaha, NE 68102 Seating in the media work room will not be assigned. COVID-19 Guidelines Internet Getty Images All credentialed, on-site media must adhere to the COVID-19 health and safety Wireless internet access will be available throughout the various media work areas. protocols listed at www.usaswimming.org/trials. Media members must receive a Ethernet connections will be available in the Media Seating Area (tables only), 2020 U.S. Olympic Team Trials - Swimming Media Guide COVID-19 PCR test 3-6 days before picking up their credentials in Omaha. select photographer locations and the Media Work Room. usaswimming.org/trials l @USASwimming l @USASwimmingNews l #SwimTrials21 Credentials Photographer Guidelines Competition Details Media credential pick-up will be located at the media entrance of the CHI Health Steven Currie will again serve as the photo chief for the U.S. Olympic Team Trials - Center Omaha. The entrance is located at the back of the building (east side of the Swimming. He will assist and coordinate locations for all photographers in Omaha. Wave I Dates: June 4-7, 2021 building), adjacent to Parking Lot A. This will be the media entrance throughout the Complete guidelines will be distributed to all credentialed photographers prior to Wave II Dates: June 13-20, 2021 me11-1et. -

Investment Guide

Investment guide The port of Antwerp, an international integrated platform ith this investment guide we seek to support you W in your decision-making process to realize an investment project in the heart of Europe. The Port of Antwerp is a crucial link in a supply chain that connects you to the inner European market and the rest of the world. With an annual volume of more than 200 million tons of maritime freight handled, the extensive storage capacity and the presence of the largest petrochemical cluster in Europe, the Port of Antwerp NADA CA Antwerp is the largest maritime, logistics and ND A A industrial cluster in Europe. US CA RI MEDITE E RR M A A N N E Good nautical access, a dense TI AN LA M of hinterland connections I network D D L E CONNECTING and its geographical location are just E A S T the top three in the list of advantages. / IS C In addition, the Port of Antwerp offers YOUR an attractive investment climate in INVESTMENT IA an innovative environment, with A S USTRALIA/ A a wide range of support, excellent A TO THE WORLD quality of life for expats and a can-do FRICA mentality that pervades the entire port community. N REGIO PACIFIC 2 Investment guide Investment guide 3 oslo Stockholm t ANTWERP Denmark Copenhagen IN WESTERN EUROPE IE NL Dublin Berlin Berlin Amsterdam Great Britain London Antwerp PL Germany Brussels BE Prague Luxembourg CZ 250 km Paris Wien NADA Bern Austria CA Antwerp ND 500 km A A Switzerland Ljubjana US France Zagreb CA RI MEDITE SL E RR HR M A A N N E TI AN LA 750 km BA M ID D L E CONNECTING Italy E A S T / IS Rome C Spain YOUR Madrid INVESTMENT IA A S PT USTRALIA/ A NL Lisbon A TO THE WORLD FRICA Antwerp t ANTWERP IN BELGIUM 45 km Flanders DE N Brussels REGIO PACIFIC BELGIUM Wallonia FR LUX 4 Investment guide 5 Investment guide Investment guide 1 Your choice to invest in the port of Antwerp is We offer you a cluster with room to invest in a future the right one for many reasons. -

Detailed List of Performances in the Six Selected Events

Detailed list of performances in the six selected events 100 metres women 100 metres men 400 metres women 400 metres men Result Result Result Result Year Athlete Country Year Athlete Country Year Athlete Country Year Athlete Country (sec) (sec) (sec) (sec) 1928 Elizabeth Robinson USA 12.2 1896 Tom Burke USA 12.0 1964 Betty Cuthbert AUS 52.0 1896 Tom Burke USA 54.2 Stanislawa 1900 Frank Jarvis USA 11.0 1968 Colette Besson FRA 52.0 1900 Maxey Long USA 49.4 1932 POL 11.9 Walasiewicz 1904 Archie Hahn USA 11.0 1972 Monika Zehrt GDR 51.08 1904 Harry Hillman USA 49.2 1936 Helen Stephens USA 11.5 1906 Archie Hahn USA 11.2 1976 Irena Szewinska POL 49.29 1908 Wyndham Halswelle GBR 50.0 Fanny Blankers- 1908 Reggie Walker SAF 10.8 1980 Marita Koch GDR 48.88 1912 Charles Reidpath USA 48.2 1948 NED 11.9 Koen 1912 Ralph Craig USA 10.8 Valerie Brisco- 1920 Bevil Rudd SAF 49.6 1984 USA 48.83 1952 Marjorie Jackson AUS 11.5 Hooks 1920 Charles Paddock USA 10.8 1924 Eric Liddell GBR 47.6 1956 Betty Cuthbert AUS 11.5 1988 Olga Bryzgina URS 48.65 1924 Harold Abrahams GBR 10.6 1928 Raymond Barbuti USA 47.8 1960 Wilma Rudolph USA 11.0 1992 Marie-José Pérec FRA 48.83 1928 Percy Williams CAN 10.8 1932 Bill Carr USA 46.2 1964 Wyomia Tyus USA 11.4 1996 Marie-José Pérec FRA 48.25 1932 Eddie Tolan USA 10.3 1936 Archie Williams USA 46.5 1968 Wyomia Tyus USA 11.0 2000 Cathy Freeman AUS 49.11 1936 Jesse Owens USA 10.3 1948 Arthur Wint JAM 46.2 1972 Renate Stecher GDR 11.07 Tonique Williams- 1948 Harrison Dillard USA 10.3 1952 George Rhoden JAM 45.9 2004 BAH 49.41 1976 -

Port of Antwerp-Bruges Structure Port of Antwerp-Bruges Is a Limited

Port of Antwerp-Bruges Structure History Port of Antwerp-Bruges is a limited liability company under public law, in Early 2018 Start of discussions between the which the City of Antwerp and the City of Bruges are the sole shareholders. City of Antwerp and the City of Bruges with a view to closer Ownership of the shares is distributed as follows: collaboration City of Antwerp: 80.2% June 2018 Economic complementarity and robustness study City of Bruges: 19.8% Registered office: Zaha Hadidplein 1, B-2030 Antwerp December 2019 Start of negotiations Organisation 12 February Signature of the two-city 2021 agreement between the Board of directors municipal executives of Antwerp and Bruges . Chair: Annick De Ridder . Vice-chair: Dirk De fauw March 2021 Under approval of the municipal . City of Bruges: 3 representatives, including vice-chair Dirk De fauw councils of Antwerp and Bruges, . City of Antwerp: 6 representatives, including chair Annick De Ridder after which the proposal will be . Independent members: 4 representatives referred to the competition authorities Executive Committee Launch of integration process . Nominated CEO: Jacques Vandermeiren The transaction is subject to a number of customary suspensory conditions, including the need to obtain approval from the Belgian competition authorities. Both parties will endeavour to complete the transaction during the course of 2021. A world port ... By joining forces, the ports of Antwerp and Zeebrugge will strengthen their position within the global logistical chain. Port of Antwerp Port