Exploring the Roots of Chronic Underdevelopment: the Colonial <I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Southern Denmark

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN DENMARK THE CHRISTIAN KINGDOM AS AN IMAGE OF THE HEAVENLY KINGDOM ACCORDING TO ST. BIRGITTA OF SWEDEN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY INSTITUTE OF HISTORY, CULTURE AND CIVILISATION CENTRE FOR MEDIEVAL STUDIES BY EMILIA ŻOCHOWSKA ODENSE FEBRUARY 2010 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In my work, I had the privilege to be guided by three distinguished scholars: Professor Jacek Salij in Warsaw, and Professors Tore Nyberg and Kurt Villads Jensen in Odense. It is a pleasure to admit that this study would never been completed without the generous instruction and guidance of my masters. Professor Salij introduced me to the world of ancient and medieval theology and taught me the rules of scholarly work. Finally, he encouraged me to search for a new research environment where I could develop my skills. I found this environment in Odense, where Professor Nyberg kindly accepted me as his student and shared his vast knowledge with me. Studying with Professor Nyberg has been a great intellectual adventure and a pleasure. Moreover, I never would have been able to work at the University of Southern Denmark if not for my main supervisor, Kurt Villads Jensen, who trusted me and decided to give me the opportunity to study under his kind tutorial, for which I am exceedingly grateful. The trust and inspiration I received from him encouraged me to work and in fact made this study possible. Karen Fogh Rasmussen, the secretary of the Centre of Medieval Studies, had been the good spirit behind my work. -

Spanish Heritage.Pages

Heritage in Micronesia SPANISH PROGRAM FOR CULTURAL COOPERATION with the collaboration of the GUAM PRESERVATION TRUST and the HISTORIC RESOURCES DIVISION, DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION Spanish Spanish Program for Cultural Cooperation Conference Spanish Heritage in Micronesia Inventory and Assessment October 16, 2008 Hyatt Regency, Tumon Guam Spanish Program for Cultural Cooperation with the collaboration of the Guam Preservation Trust and the Historic Resources Division, Guam Department of Parks and Recreation Table of Contents Spanish Heritage in Micronesia: Inventory and Assessment 1 By Judith S. Flores, PhD Spanish Heritage Resources In The Mariana Islands 5 By Judith S. Flores, PhD The Archaeology of Spanish Period, Guam 11 By John A. Peterson Inventory and Assessment of Spanish Tangible Heritage in the Federated States of Micronesia 32 By Rufino Mauricio Heritage Preservation And Sustainability: Technical Recommendations And Community Participation 44 By Maria Lourdes Joy Martinez-Onozawa Historic Inalahan Field Workshop 52 By Judith S. Flores, PhD Spanish Heritage in Palau 61 By Filly Carabit and Errolflynn Kloulechad Spanish Heritage in Micronesia: Inventory and Assessment Introduction By Judith S. Flores, PhD President, Historic Inalahan Foundation, Inc. The second in a series of conferences funded by the Spanish Program for Cultural Cooperation (SPCC) opened in the Hyatt-Regency in Tumon, Guam on October 16, 2008. The first conference sponsored by SPCC was held the previous year in Guam on Nov. 14-15, 2007, entitled “Stonework Heritage in Micronesia”, organized by the Guam Preservation Trust. It brought together and introduced technical experts in Spanish stonework and Spanish heritage architects to a gathering of historic preservation officials and scholars who live and work in Guam and Micronesia. -

Q Kevin Ginter, 1998

CACIQUISMO IN MEXICO: A STUDY IN POST-REVOLUTIONARY HISTQRIOGRAPHY Mémoire présenté à Ia Faculté des études supérieures de L'Université Lava1 pour l'obtention du grade de maître ès arts (M.A) Département d'histoire FAcULTÉ DES LETTRES WNNERSITÉ LAVAL Q Kevin Ginter, 1998 National Libmry Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services seMces bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada The author bas granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seU reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts from it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Table of Contents Foreword.. ..................................................... -......,.-.,.,...II Introduction .......................1 . Objectives...................................................................... -1 Kistoriographical -

Early Colonial History Four of Seven

Early Colonial History Four of Seven Marianas History Conference Early Colonial History Guampedia.com This publication was produced by the Guampedia Foundation ⓒ2012 Guampedia Foundation, Inc. UOG Station Mangilao, Guam 96923 www.guampedia.com Table of Contents Early Colonial History Windfalls in Micronesia: Carolinians' environmental history in the Marianas ...................................................................................................1 By Rebecca Hofmann “Casa Real”: A Lost Church On Guam* .................................................13 By Andrea Jalandoni Magellan and San Vitores: Heroes or Madmen? ....................................25 By Donald Shuster, PhD Traditional Chamorro Farming Innovations during the Spanish and Philippine Contact Period on Northern Guam* ....................................31 By Boyd Dixon and Richard Schaefer and Todd McCurdy Islands in the Stream of Empire: Spain’s ‘Reformed’ Imperial Policy and the First Proposals to Colonize the Mariana Islands, 1565-1569 ....41 By Frank Quimby José de Quiroga y Losada: Conquest of the Marianas ...........................63 By Nicholas Goetzfridt, PhD. 19th Century Society in Agaña: Don Francisco Tudela, 1805-1856, Sargento Mayor of the Mariana Islands’ Garrison, 1841-1847, Retired on Guam, 1848-1856 ...............................................................................83 By Omaira Brunal-Perry Windfalls in Micronesia: Carolinians' environmental history in the Marianas By Rebecca Hofmann Research fellow in the project: 'Climates of Migration: -

Historical Origins of the One-Drop Racial Rule in the United States

Historical Origins of the One-Drop Racial Rule in the United States Winthrop D. Jordan1 Edited by Paul Spickard2 Editor’s Note Winthrop Jordan was one of the most honored US historians of the second half of the twentieth century. His subjects were race, gender, sex, slavery, and religion, and he wrote almost exclusively about the early centuries of American history. One of his first published articles, “American Chiaroscuro: The Status and Definition of Mulattoes in the British Colonies” (1962), may be considered an intellectual forerunner of multiracial studies, as it described the high degree of social and sexual mixing that occurred in the early centuries between Africans and Europeans in what later became the United States, and hinted at the subtle racial positionings of mixed people in those years.3 Jordan’s first book, White over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro, 1550–1812, was published in 1968 at the height of the Civil Rights Movement era. The product of years of painstaking archival research, attentive to the nuances of the thousands of documents that are its sources, and written in sparkling prose, White over Black showed as no previous book had done the subtle psycho-social origins of the American racial caste system.4 It won the National Book Award, the Ralph Waldo Emerson Prize, the Bancroft Prize, the Parkman Prize, and other honors. It has never been out of print since, and it remains a staple of the graduate school curriculum for American historians and scholars of ethnic studies. In 2005, the eminent public intellectual Gerald Early, at the request of the African American magazine American Legacy, listed what he believed to be the ten most influential books on African American history. -

Redalyc.Encomienda, Mujeres Y Patriarcalismo Difuso: Las

Historia Crítica ISSN: 0121-1617 [email protected] Universidad de Los Andes Colombia Zambrano, Camilo Alexander Encomienda, mujeres y patriarcalismo difuso: las encomenderas de Santafé y Tunja (1564-1636) Historia Crítica, núm. 44, mayo-agosto, 2011, pp. 10-31 Universidad de Los Andes Bogotá, Colombia Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=81122472002 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto 10 Encomienda, mujeres y patriarcalismo difuso: las encomenderas de Santafé y Tunja (1564-1636) ARTÍCULO RECIBIDO: 8 DE Encomienda, mujeres y patriarcalismo The encomienda, women, and diffuse ABRIL DE 2010; APRO- difuso: las encomenderas de Santafé y patriarchy: the encomenderas of BADO: 6 DE SEPTIEMBRE DE Tunja (1564-1636) Santafé and Tunja (1564-1636) 2010; MODIFICADO: 30 DE ENERO DE 2011. RESUMEN ABSTRACT Este artículo aborda el tema de las encomenderas This article examines the topic of encomenderas en la historiografía colombiana, mostrando los (women encomienda-holders) in Colombian histo- sucesos que las evocan, el gesto que las silencia y riography, showing the events that evoke them, the cómo las recupera la historia. A continuación ana- gesture that silences them, and how history recupera- liza la participación social, económica y política de tes them. Then it analyzes the social, economic, and las mujeres en el Nuevo Reino durante el período political participation of women in the New Kingdom colonial. -

New Spain and Early Independent Mexico Manuscripts New Spain Finding Aid Prepared by David M

New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts New Spain Finding aid prepared by David M. Szewczyk. Last updated on January 24, 2011. PACSCL 2010.12.20 New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts Table of Contents Summary Information...................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History.........................................................................................................................................3 Scope and Contents.......................................................................................................................................6 Administrative Information...........................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory..................................................................................................................................... 9 - Page 2 - New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts Summary Information Repository PACSCL Title New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts Call number New Spain Date [inclusive] 1519-1855 Extent 5.8 linear feet Language Spanish Cite as: [title and date of item], [Call-number], New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts, 1519-1855, Rosenbach Museum and Library. Biography/History Dr. Rosenbach and the Rosenbach Museum and Library During the first half of this century, Dr. Abraham S. W. Rosenbach reigned supreme as our nations greatest bookseller. -

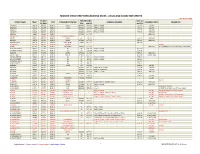

Residential Resurfacing List

MISSION VIEJO STREET RESURFACING INDEX - LOCAL AND COLLECTOR STREETS Rev. DEC 31, 2020 TB MAP RESURFACING LAST AC STREET NAME TRACT TYPE COMMUNITY/OWNER ADDRESS NUMBERS PAVEMENT INFO COMMENTS PG GRID TYPE MO/YR MO/YR ABADEJO 09019 892 E7 PUBLIC OVGA RPMSS1 OCT 18 28241 to 27881 JUL 04 .4AC/NS ABADEJO 09018 892 E7 PUBLIC OVGA RPMSS1 OCT 18 27762 to 27832 JUL 04 .4AC/NS ABANICO 09566 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 27551 to 27581 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ABANICO 09568 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 27541 to 27421 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ABEDUL 09563 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 .35AC/NS ABERDEEN 12395 922 C7 PRIVATE HIGHLAND CONDOS -- ABETO 08732 892 D5 PUBLIC MVEA AC JUL 15 JUL 15 .35AC/NS ABRAZO 09576 892 D3 PUBLIC MVEA RPMSS OCT 17 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ACACIA COURT 08570 891 J6 PUBLIC TIMBERLINE TRMSS OCT 14 AUG 08 ACAPULCO 12630 892 F1 PRIVATE PALMIA -- GATED ACERO 79-142 892 A6 PUBLIC HIGHPARK TRMSS OCT 14 .55AC/NS 4/1/17 TRMSS 40' S of MAQUINA to ALAMBRE ACROPOLIS DRIVE 06667 922 A1 PUBLIC AH AC AUG 08 24582 to 24781 AUG 08 ACROPOLIS DRIVE 07675 922 A1 PUBLIC AH AC AUG 08 24801 to 24861 AUG 08 ADELITA 09078 892 D4 PUBLIC MVEA RPMSS OCT 17 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ADOBE LANE 06325 922 C1 PUBLIC MVSRC RPMSS OCT 17 AUG 08 .17SAC/.58AB ADONIS STREET 06093 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 24161 to 24232 SEP 14 ADONIS STREET 06092 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 24101 to 24152 SEP 14 ADRIANA STREET 06092 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 SEP 14 AEGEA STREET 06093 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 SEP 14 AGRADO 09025 922 D1 PUBLIC OVGA AC AUG 18 AUG 18 .4AC/NS AGUILAR 09255 892 D1 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 PINAVETE -

Antonio De Mendoza; First Viceroy of Mexico. the Tinker Pamphlet

.4. DOCUMENT RESUME ED 114 227 RC 008' 850- AUTHOR Miller, Hubert J. TITLE Antonio de Mendola; First Viceroy of Mexico. The Tinker Pamphlet Series for the Teaching of.Mexican American Heritage. TB 73 NOTE 70p.; For related documents, see RC 008 851-853 AVAtLABL ROM' Mr. Al Ramirez, P.O. Box 471, Edinburg, Texas.78539 ($1.00) EDRS PRICE. MF-$0.76 Plus Postage. HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTO ji5*Administrator Background; American Indians; - *Biographies; Colonialism; Cultiral Education; Curriculum Enrichment; Curriculum Guides; Elementary Secondary Education; *Mexican.AmerieHistory; *Mexicaps; Resource Materials; Sociocultural Patterns; Vocabulait; *Western Civiliiation IDENTIFIERS *Mendoza (Antonio de) ABSTRACT .0 As Mexico's first viceroy, Antonio de Mendoza.s most noteworthy achievement was his laYing the basis of colonial government in New Spain which continued, with modifications, for 300. years. Although he was lenient in dealing with the shortcomingi of .his Indian and Spanish subjects; he took a'firm stand in dealing with the rebellious Indians in the Mixton War and the Cortes faction which threatened the Viceregal rule. His pridary concern was to keep New Spain for the crown while protecting the Indians from w#nt.and . inhumanity. Focusing o$ the institutions he founded and 'developed, this booklet provides a study of early Spanish colonial institutions. Although the biographical account is of secondary importance, the. description .of Hispanic colonial institutions arelPable'in presenting the Spaniards. colonization after the cconquest -ctica. applicAtion of the, material at both the elementary and 'se levels can be utilized in stimulating student discussionsa on the Merits and demerits of 2 colonial powers- -the English a the Spaniards. -

The Deveiopment and Functions of the Army In

The development and functions of the army in new Spain, 1760-1798 Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Peloso, Vincent C. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 23/09/2021 10:56:36 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/319751 THE DEVEIOPMENT AND FUNCTIONS OF THE ARMY IN NEW SPAIN, 1760-1798 Vincent Peloso A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 6 5 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduc tion of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of schol arship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. -

DOWNLOAD Primerang Bituin

A publication of the University of San Francisco Center for the Pacific Rim Copyright 2006 Volume VI · Number 1 15 May · 2006 Special Issue: PHILIPPINE STUDIES AND THE CENTENNIAL OF THE DIASPORA Editors Joaquin Gonzalez John Nelson Philippine Studies and the Centennial of the Diaspora: An Introduction Graduate Student >>......Joaquin L. Gonzalez III and Evelyn I. Rodriguez 1 Editor Patricia Moras Primerang Bituin: Philippines-Mexico Relations at the Dawn of the Pacific Rim Century >>........................................................Evelyn I. Rodriguez 4 Editorial Consultants Barbara K. Bundy Hartmut Fischer Mail-Order Brides: A Closer Look at U.S. & Philippine Relations Patrick L. Hatcher >>..................................................Marie Lorraine Mallare 13 Richard J. Kozicki Stephen Uhalley, Jr. Apathy to Activism through Filipino American Churches Xiaoxin Wu >>....Claudine del Rosario and Joaquin L. Gonzalez III 21 Editorial Board Yoko Arisaka The Quest for Power: The Military in Philippine Politics, 1965-2002 Bih-hsya Hsieh >>........................................................Erwin S. Fernandez 38 Uldis Kruze Man-lui Lau Mark Mir Corporate-Community Engagement in Upland Cebu City, Philippines Noriko Nagata >>........................................................Francisco A. Magno 48 Stephen Roddy Kyoko Suda Worlds in Collision Bruce Wydick >>...................................Carlos Villa and Andrew Venell 56 Poems from Diaspora >>..................................................................Rofel G. Brion -

La Última Voluntad Del Diputado Quiteño José Mexía De Lequerica1

ISSN 1696-0300 LA ÚLTIMA VOLUNTAD DEL DIPUTADO QUITEÑO JOSÉ MEXÍA DE LEQUERICA 1 Gloria de los Ángeles ZARZA RONDÓN Universidad de Cádiz RESUMEN: El artículo que presentamos pretende aclarar distintos datos historiográficos sobre la vida del diputado a Cortes por el Nuevo Reino de Granada, José Mexía de Lequerica. A través de la documentación consultada en los Archivos Históricos, Municipal y Provincial de Cádiz, además del Archivo Parroquial de San Antonio, hemos descubierto cuál fue su verdadera ubicación urbanística, con quiénes compartió el final de su vida, cuáles fueron sus últimas voluntades antes de fallecer, y cómo éstas se llevaron a cabo por sus albaceas testamentarios, ofreciendo así un panorama completo, y hasta ahora desconocido, sobre los últimos años de uno de los diputados hispanoamericanos más trascendentales del Cádiz doceañista. PALABRAS CLAVE: Protocolo notarial, Nuevo Reino de Granada, acta de defunción, padrón, Cortes de Cádiz. ABSTRACT: The article that we sense beforehand tries to clarify different information historiográficos on the life of the deputy to Spanish Parliament for the New Kingdom of Granada, Jose Mexía de Lequerica. Across the documentation consulted in the Historical, Municipal and Provincial Files of Cadiz, besides the Parochial File of San Antonio, we have discovered which was his real urban development location, with whom he shared the end of his life, which were his last wills before expiring, and how these were carried out by his testamentary executors, offering this way a complete panorama, and till now unknown, on the last years of one of the most transcendental Spanish-American deputies of the Cadiz doceañista.