I. Linnaean Taxonomy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revised Glossary for AQA GCSE Biology Student Book

Biology Glossary amino acids small molecules from which proteins are A built abiotic factor physical or non-living conditions amylase a digestive enzyme (carbohydrase) that that affect the distribution of a population in an breaks down starch ecosystem, such as light, temperature, soil pH anaerobic respiration respiration without using absorption the process by which soluble products oxygen of digestion move into the blood from the small intestine antibacterial chemicals chemicals produced by plants as a defence mechanism; the amount abstinence method of contraception whereby the produced will increase if the plant is under attack couple refrains from intercourse, particularly when an egg might be in the oviduct antibiotic e.g. penicillin; medicines that work inside the body to kill bacterial pathogens accommodation ability of the eyes to change focus antibody protein normally present in the body acid rain rain water which is made more acidic by or produced in response to an antigen, which it pollutant gases neutralises, thus producing an immune response active site the place on an enzyme where the antimicrobial resistance (AMR) an increasing substrate molecule binds problem in the twenty-first century whereby active transport in active transport, cells use energy bacteria have evolved to develop resistance against to transport substances through cell membranes antibiotics due to their overuse against a concentration gradient antiretroviral drugs drugs used to treat HIV adaptation features that organisms have to help infections; they -

Linn E and Taxonomy in Japan: on the 300Th Anniversary of His Birth

No. 3] Proc. Jpn. Acad., Ser. B 86 (2010) 143 Linne and taxonomy in Japan: On the 300th anniversary of his birth By Akihito (His Majesty The Emperor of Japan) (Communicated by Koichiro TSUNEWAKI, M.J.A.) President, dear friends bers of stamens belonged to dierent classes, even when their other characteristics were very similar, I am very grateful to the Linnean Society of while species with the same number of stamens be- London for the kind invitation it extended to me to longed to the same class, even when their other participate in the celebration of the 300th anniver- characteristics were very dierent. This led to the sary of the birth of Carl von Linne. When, in 1980, I idea that the classication of organisms should be was elected as a foreign member of the Society, I felt based on a more comprehensive evaluation of all I did not really deserve the honour, but it has given their characteristics. This idea gained increasing me great encouragement as I have tried to continue support, and Linne’s classication system was even- my research, nding time between my ofcial duties. tually replaced by systems based on phylogeny. Today, I would like to speak in memory of Carl The binomial nomenclature proposed by Linne, von Linne, and address the question of how Euro- however, became the basis of the scientic names of pean scholarship has developed in Japan, touching animals and plants, which are commonly used in the upon the work of people like Carl Peter Thunberg, world today, not only by people in academia but also Linne’s disciple who stayed in Japan for a year as by the general public. -

Botanical Nomenclature: Concept, History of Botanical Nomenclature

Module – 15; Content writer: AvishekBhattacharjee Module 15: Botanical Nomenclature: Concept, history of botanical nomenclature (local and scientific) and its advantages, formation of code. Content writer: Dr.AvishekBhattacharjee, Central National Herbarium, Botanical Survey of India, P.O. – B. Garden, Howrah – 711 103. Module – 15; Content writer: AvishekBhattacharjee Botanical Nomenclature:Concept – A name is a handle by which a mental image is passed. Names are just labels we use to ensure we are understood when we communicate. Nomenclature is a mechanism for unambiguous communication about the elements of taxonomy. Botanical Nomenclature, i.e. naming of plants is that part of plant systematics dealing with application of scientific names to plants according to some set rules. It is related to, but distinct from taxonomy. A botanical name is a unique identifier to which information of a taxon can be attached, thus enabling the movement of data across languages, scientific disciplines, and electronic retrieval systems. A plant’s name permits ready summarization of information content of the taxon in a nested framework. A systemofnamingplantsforscientificcommunicationmustbe international inscope,andmustprovideconsistencyintheapplicationof names.Itmustalsobeacceptedbymost,ifnotall,membersofthe scientific community. These criteria led, almost inevitably, to International Botanical Congresses (IBCs) being the venue at which agreement on a system of scientific nomenclature for plants was sought. The IBCs led to publication of different ‘Codes’ which embodied the rules and regulations of botanical nomenclature and the decisions taken during these Congresses. Advantages ofBotanical Nomenclature: Though a common name may be much easier to remember, there are several good reasons to use botanical names for plant identification. Common names are not unique to a specific plant. -

18.4 Bacteria and Archaea Kingdom Eubacteria Domain Bacteria

18.4 Bacteria and Archaea Kingdom Eubacteria Domain Bacteria 18.4 Bacteria and Archaea Description Bacteria are single-celled prokaryotes. 18.4 Bacteria and Archaea Where do they live? Prokaryotes are widespread on Earth. ( Est. over 1 billion types of bacteria, and over 1030 individual prokaryote cells on earth.) Found in all land and ocean environments, even inside other organisms! 18.4 Bacteria and Archaea Common Examples • E. Coli • Tetanus bacteria • Salmonella bacteria • Tuberculosis bacteria • Staphylococcus • Streptococcus 18.4 Bacteria and Archaea Modes Of Nutrition • Bacteria may be heterotrophs or autotrophs 18.4 Bacteria and Archaea Bacteria Reproduce How? • by binary fission. • exchange genes during conjugation= conjugation bridge increases diversity. • May survive by forming endospores = specialized cell with thick protective cell wall. TEM; magnification 6000x • Can survive for centuries until environment improves. Have been found in mummies! 18.4 Bacteria and Archaea • Bacteria Diagram – plasmid = small piece of genetic material, can replicate independently of the chromosome – flagellum = different than in eukaryotes, but for movement – pili = used to stick the bacteria to eachpili other or surfaces plasma membrance flagellum chromosome cell wall plasmid This diagram shows the typical structure of a prokaryote. Archaea and bacteria look very similar, although they have important molecular differences. 18.4 Bacteria and Archaea • Classified by: their need for oxygen, how they gram stain, and their shapes 18.4 Bacteria and Archaea Main Groups by Shapes – rod-shaped, called bacilli – spiral, called spirilla or spirochetes – spherical, called cocci Spirochaeta: spiral Lactobacilli: rod-shaped Enterococci: spherical 18.4 Bacteria and Archaea • Main Groups by their need for oxygen. -

Historical Review of Systematic Biology and Nomenclature - Alessandro Minelli

BIOLOGICAL SCIENCE FUNDAMENTALS AND SYSTEMATICS – Vol. II - Historical Review of Systematic Biology and Nomenclature - Alessandro Minelli HISTORICAL REVIEW OF SYSTEMATIC BIOLOGY AND NOMENCLATURE Alessandro Minelli Department of Biology, Via U. Bassi 58B, I-35131, Padova,Italy Keywords: Aristotle, Belon, Cesalpino, Ray, Linnaeus, Owen, Lamarck, Darwin, von Baer, Haeckel, Sokal, Sneath, Hennig, Mayr, Simpson, species, taxa, phylogeny, phenetic school, phylogenetic school, cladistics, evolutionary school, nomenclature, natural history museums. Contents 1. The Origins 2. From Classical Antiquity to the Renaissance Encyclopedias 3. From the First Monographers to Linnaeus 4. Concepts and Definitions: Species, Homology, Analogy 5. The Impact of Evolutionary Theory 6. The Last Few Decades 7. Nomenclature 8. Natural History Collections Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary The oldest roots of biological systematics are found in folk taxonomies, which are nearly universally developed by humankind to cope with the diversity of the living world. The logical background to the first modern attempts to rationalize the classifications was provided by Aristotle's logic, as embodied in Cesalpino's 16th century classification of plants. Major advances were provided in the following century by Ray, who paved the way for the work of Linnaeus, the author of standard treatises still regarded as the starting point of modern classification and nomenclature. Important conceptual progress was due to the French comparative anatomists of the early 19th century UNESCO(Cuvier, Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire) – andEOLSS to the first work in comparative embryology of von Baer. Biological systematics, however, was still searching for a unifying principle that could provide the foundation for a natural, rather than conventional, classification.SAMPLE This principle wasCHAPTERS provided by evolutionary theory: its effects on classification are already present in Lamarck, but their full deployment only happened in the 20th century. -

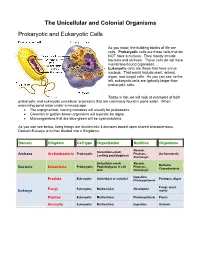

The Unicellular and Colonial Organisms Prokaryotic And

The Unicellular and Colonial Organisms Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells As you know, the building blocks of life are cells. Prokaryotic cells are those cells that do NOT have a nucleus. They mostly include bacteria and archaea. These cells do not have membrane-bound organelles. Eukaryotic cells are those that have a true nucleus. That would include plant, animal, algae, and fungal cells. As you can see, to the left, eukaryotic cells are typically larger than prokaryotic cells. Today in lab, we will look at examples of both prokaryotic and eukaryotic unicellular organisms that are commonly found in pond water. When examining pond water under a microscope… The unpigmented, moving microbes will usually be protozoans. Greenish or golden-brown organisms will typically be algae. Microorganisms that are blue-green will be cyanobacteria. As you can see below, living things are divided into 3 domains based upon shared characteristics. Domain Eukarya is further divided into 4 Kingdoms. Domain Kingdom Cell type Organization Nutrition Organisms Absorb, Unicellular-small; Prokaryotic Photsyn., Archaeacteria Archaea Archaebacteria Lacking peptidoglycan Chemosyn. Unicellular-small; Absorb, Bacteria, Prokaryotic Peptidoglycan in cell Photsyn., Bacteria Eubacteria Cyanobacteria wall Chemosyn. Ingestion, Eukaryotic Unicellular or colonial Protozoa, Algae Protista Photosynthesis Fungi, yeast, Fungi Eukaryotic Multicellular Absorption Eukarya molds Plantae Eukaryotic Multicellular Photosynthesis Plants Animalia Eukaryotic Multicellular Ingestion Animals Prokaryotic Organisms – the archaea, non-photosynthetic bacteria, and cyanobacteria Archaea - Microorganisms that resemble bacteria, but are different from them in certain aspects. Archaea cell walls do not include the macromolecule peptidoglycan, which is always found in the cell walls of bacteria. Archaea usually live in extreme, often very hot or salty environments, such as hot mineral springs or deep-sea hydrothermal vents. -

Biology Chapter 19 Kingdom Protista Domain Eukarya Description Kingdom Protista Is the Most Diverse of All the Kingdoms

Biology Chapter 19 Kingdom Protista Domain Eukarya Description Kingdom Protista is the most diverse of all the kingdoms. Protists are eukaryotes that are not animals, plants, or fungi. Some unicellular, some multicellular. Some autotrophs, some heterotrophs. Some with cell walls, some without. Didinium protist devouring a Paramecium protist that is longer than it is! Read about it on p. 573! Where Do They Live? • Because of their diversity, we find protists in almost every habitat where there is water or at least moisture! Common Examples • Ameba • Algae • Paramecia • Water molds • Slime molds • Kelp (Sea weed) Classified By: (DON’T WRITE THIS DOWN YET!!! • Mode of nutrition • Cell walls present or not • Unicellular or multicellular Protists can be placed in 3 groups: animal-like, plantlike, or funguslike. Didinium, is a specialist, only feeding on Paramecia. They roll into a ball and form cysts when there is are no Paramecia to eat. Paramecia, on the other hand are generalists in their feeding habits. Mode of Nutrition Depends on type of protist (see Groups) Main Groups How they Help man How they Hurt man Ecosystem Roles KEY CONCEPT Animal-like protists = PROTOZOA, are single- celled heterotrophs that can move. Oxytricha Reproduce How? • Animal like • Unicellular – by asexual reproduction – Paramecium – does conjugation to exchange genetic material Animal-like protists Classified by how they move. macronucleus contractile vacuole food vacuole oral groove micronucleus cilia • Protozoa with flagella are zooflagellates. – flagella help zooflagellates swim – more than 2000 zooflagellates • Some protists move with pseudopods = “false feet”. – change shape as they move –Ex. amoebas • Some protists move with pseudopods. -

Using Te Reo Māori and Ta Re Moriori in Taxonomy

VealeNew Zealand et al.: Te Journal reo Ma- oriof Ecologyin taxonomy (2019) 43(3): 3388 © 2019 New Zealand Ecological Society. 1 REVIEW Using te reo Māori and ta re Moriori in taxonomy Andrew J. Veale1,2* , Peter de Lange1 , Thomas R. Buckley2,3 , Mana Cracknell4, Holden Hohaia2, Katharina Parry5 , Kamera Raharaha-Nehemia6, Kiri Reihana2 , Dave Seldon2,3 , Katarina Tawiri2 and Leilani Walker7 1Unitec Institute of Technology, 139 Carrington Road, Mt Albert, Auckland 1025, New Zealand 2Manaaki Whenua - Landcare Research, 231 Morrin Road, St Johns, Auckland 1072, New Zealand 3School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland, 3A Symonds St, Auckland CBD, Auckland 1010, New Zealand 4Rongomaiwhenua-Moriori, Kaiangaroa, Chatham Island, New Zealand 5Massey University, Private Bag 11222 Palmerston North, 4442, New Zealand 6Ngāti Kuri, Otaipango, Ngataki, Te Aupouri, Northland, New Zealand 7Auckland University of Technology, 55 Wellesley St E, Auckland CBS, Auckland 1010, New Zealand *Author for correspondence (Email: [email protected]) Published online: 28 November 2019 Auheke: Ko ngā ingoa Linnaean ka noho hei pou mō te pārongo e pā ana ki ngā momo koiora. He mea nui rawa kia mārama, kia ahurei hoki ngā ingoa pūnaha whakarōpū. Me pēnei kia taea ai te whakawhitiwhiti kōrero ā-pūtaiao nei. Nā tēnā kua āta whakatakotohia ētahi ture, tohu ārahi hoki hei whakahaere i ngā whakamārama pūnaha whakarōpū. Kua whakamanahia ēnei kia noho hei tikanga mō te ao pūnaha whakarōpū. Heoi, arā noa atu ngā hua o te tukanga waihanga ingoa Linnaean mō ngā momo koiora i tua atu i te tautohu noa i ngā momo koiora. Ko tētahi o aua hua ko te whakarau: (1) i te mātauranga o ngā iwi takatake, (2) i te kōrero rānei mai i te iwi o te rohe, (3) i ngā kōrero pūrākau rānei mō te wāhi whenua. -

Structural Biology of the C-Terminal Domain Of

STRUCTURAL BIOLOGY OF THE C-TERMINAL DOMAIN OF EUKARYOTIC REPLICATION FACTOR MCM10 By Patrick David Robertson Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Biological Sciences August, 2010 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Brandt F. Eichman Walter J. Chazin James G. Patton Hassane Mchaourab To my wife Sabrina, thank you for your enduring love and support ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to begin by expressing my sincerest gratitude to my mentor and Ph.D. advisor, Dr. Brandt Eichman. In addition to your excellent guidance and training, your passion for science has been a source of encouragement and inspiration over the past five years. I consider working with you to be a great privilege and I am grateful for the opportunity. I would also like to thank the members of my thesis committee: Drs. Walter Chazin, Ellen Fanning, James Patton, and Hassane Mchaourab. My research and training would not have been possible without your insight, advice and intellectual contributions. I would like to acknowledge all of the members of the Eichman laboratory, past and present, for their technical assistance and camaraderie over the years. I would especially like to thank Dr. Eric Warren for his contributions to the research presented here, as well for his friendship of the years. I would also like to thank Drs. Benjamin Chagot and Sivaraja Vaithiyalingam from the Chazin laboratory for their expert assistance and NMR training. I would especially like to thank my parents, Joyce and David, my brother Jeff, and the rest of my family for their love and encouragement throughout my life. -

BIRDS AS MARINE ORGANISMS: a REVIEW Calcofi Rep., Vol

AINLEY BIRDS AS MARINE ORGANISMS: A REVIEW CalCOFI Rep., Vol. XXI, 1980 BIRDS AS MARINE ORGANISMS: A REVIEW DAVID G. AINLEY Point Reyes Bird Observatory Stinson Beach, CA 94970 ABSTRACT asociadas con esos peces. Se indica que el estudio de las Only 9 of 156 avian families are specialized as sea- aves marinas podria contribuir a comprender mejor la birds. These birds are involved in marine energy cycles dinamica de las poblaciones de peces anterior a la sobre- during all aspects of their lives except for the 10% of time explotacion por el hombre. they spend in some nesting activities. As marine organ- isms their occurrence and distribution are directly affected BIRDS AS MARINE ORGANISMS: A REVIEW by properties of their oceanic habitat, such as water temp- As pointed out by Sanger(1972) and Ainley and erature, salinity, and turbidity. In their trophic relation- Sanger (1979), otherwise comprehensive reviews of bio- ships, almost all are secondary or tertiary carnivores. As logical oceanography have said little or nothing about a group within specific ecosystems, estimates of their seabirds in spite of the fact that they are the most visible feeding rates range between 20 and 35% of annual prey part of the marine biota. The reasons for this oversight are production. Their usual prey are abundant, schooling or- no doubt complex, but there are perhaps two major ones. ganisms such as euphausiids and squid (invertebrates) First, because seabirds have not been commercially har- and clupeids, engraulids, and exoccetids (fish). Their high vested to any significant degree, fisheries research, which rates of feeding and metabolism, and the large amounts of supplies most of our knowledge about marine ecosys- nutrients they return to the marine environment, indicate tems, has ignored them. -

Why Mammals Are Called Mammals: Gender Politics in Eighteenth-Century Natural History Author(S): Londa Schiebinger Source: the American Historical Review, Vol

Why Mammals are Called Mammals: Gender Politics in Eighteenth-Century Natural History Author(s): Londa Schiebinger Source: The American Historical Review, Vol. 98, No. 2 (Apr., 1993), pp. 382-411 Published by: American Historical Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2166840 Accessed: 22/01/2010 10:27 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=aha. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. American Historical Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The American Historical Review. http://www.jstor.org Why Mammals Are Called Mammals: Gender Politics in Eighteenth-Century Natural History LONDA SCHIEBINGER IN 1758, IN THE TENTH EDITION OF HIS Systema naturae, Carolus Linnaeus introduced the term Mammaliainto zoological taxonomy. -

A Knowledge-Centric E-Research Platform for Marine Life and Oceanographic Research

A KNOWLEDGE-CENTRIC E-RESEARCH PLATFORM FOR MARINE LIFE AND OCEANOGRAPHIC RESEARCH Ali Daniyal, Samina Abidi, Ashraf AbuSharekh, Mei Kuan Wong and S. S. R. Abidi Department of Computer Science, Dalhousie University, 6050 Univeristy Ave, Halifax, Canada Keywords: e-Research, Knowledge management, Web services, Marine life, Oceanography. Abstract: In this paper we present a knowledge centric e-Research platform to support collaboration between two diverse scientific communities—i.e. Oceanography and Marine Life domains. The Platform for Ocean Knowledge Management (POKM) offers a services oriented framework to facilitate the sharing, discovery and visualization of multi-modal data and scientific models. To establish interoperability between two diverse domain, we have developed a common OWL-based domain ontology that captures and interrelates concepts from the two different domain. POKM also provide semantic descriptions of the functionalities of a range of e-research oriented web services through a OWL-S service ontology that supports dynamic discovery and invocation of services. POKM has been deployed as a web-based prototype system that is capable of fetching, sharing and visualizing marine animal detection and oceanographic data from multiple global data sources. 1 INTRODUCTION (POKM)—that offers a suite of knowledge-centric services for oceanographic researchers to (a) access, To comprehensively understand how changes to the share, integrate and operationalize the data, models ecosystem impact the ocean’s physical and and knowledge resources available at multiple sites; biological parameters (Cummings, 2005) (b) collaborate in joint scientific research oceanographers and marine biologists—termed as experiments by sharing resources, results, expertise the oceanographic research community—are seeking and models; and (c) form a virtual community of more collaboration in terms of sharing domain- researchers, marine resource managers, policy specific data and knowledge (Bos, 2007).