BIRDS AS MARINE ORGANISMS: a REVIEW Calcofi Rep., Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pacific Seabirds

PACIFIC SEABIRDS A Publication of the Pacific Seabird Group Volume 34 Number 1 Spring 2007 PACIFIC SEABIRD GROUP Dedicated to the Study and Conservation of Pacific Seabirds and Their Environment The Pacific Seabird Group (PSG) was formed in 1972 due to the need for better communication among Pacific seabird researchers. PSG provides a forum for the research activities of its members, promotes the conservation of seabirds, and informs members and the public of issues relating to Pacific Ocean seabirds and their environment. PSG holds annual meetings at which scientific papers and symposia are presented. The group’s journals are Pacific Seabirds(formerly the PSG Bulletin), and Marine Ornithology (published jointly with the African Seabird Group, Australasian Seabird Group, Dutch Seabird Group, and The Seabird Group [United King- dom]; www.marineornithology.org). Other publications include symposium volumes and technical reports. Conservation concerns include seabird/fisheries interactions, monitoring of seabird populations, seabird restoration following oil spills, establishment of seabird sanctuaries, and endangered species. Policy statements are issued on conservation issues of critical importance. PSG mem- bers include scientists, conservation professionals, and members of the public from both sides of the Pacific Ocean. It is hoped that seabird enthusiasts in other parts of the world also will join and participate in PSG. PSG is a member of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the Ornithological Council, and. the American Bird Conservancy. Annual dues for membership are $25 (individual and family); $15 (student, undergraduate and graduate); and $750 (Life Membership, payable in five $150 install- ments). Dues are payable to the Treasurer; see Membership/Order Form next to inside back cover for details and application. -

Revised Glossary for AQA GCSE Biology Student Book

Biology Glossary amino acids small molecules from which proteins are A built abiotic factor physical or non-living conditions amylase a digestive enzyme (carbohydrase) that that affect the distribution of a population in an breaks down starch ecosystem, such as light, temperature, soil pH anaerobic respiration respiration without using absorption the process by which soluble products oxygen of digestion move into the blood from the small intestine antibacterial chemicals chemicals produced by plants as a defence mechanism; the amount abstinence method of contraception whereby the produced will increase if the plant is under attack couple refrains from intercourse, particularly when an egg might be in the oviduct antibiotic e.g. penicillin; medicines that work inside the body to kill bacterial pathogens accommodation ability of the eyes to change focus antibody protein normally present in the body acid rain rain water which is made more acidic by or produced in response to an antigen, which it pollutant gases neutralises, thus producing an immune response active site the place on an enzyme where the antimicrobial resistance (AMR) an increasing substrate molecule binds problem in the twenty-first century whereby active transport in active transport, cells use energy bacteria have evolved to develop resistance against to transport substances through cell membranes antibiotics due to their overuse against a concentration gradient antiretroviral drugs drugs used to treat HIV adaptation features that organisms have to help infections; they -

Marine Vertebrate Conservation (Including Threatened and Protected Species)

Marine Vertebrate Conservation (including Threatened and Protected Species) Submission for National Marine Science Plan, White paper submissions for Biodiversity Conservation and Ecosystem Health Coordinated by Professor Peter L. Harrison Abstract A diverse range of important and endemic marine vertebrate species occurs in Australia’s vast marine area. Australian scientists produce significant proportions of global research on marine vertebrates, and are internationally recognised leaders in some fields including conservation and management. Many end-users require this knowledge, but relatively few species have been studied sufficiently to determine their conservation status hence data deficiency is a major problem for management. Key science needs include improved taxonomic, distribution, demographic and trend data from long-term funded programs, improved threat mitigation to ensure sustainability, and development of national marine vertebrate science hub(s) to co-ordinate and integrate future research. Background An extraordinary diversity of marine vertebrate species occurs in Australia’s vast >10 million km2 marine territorial sea and EEZ and Australian Antarctic Territory waters, which encompass shallow coastal to deep ocean ecosystems from tropical to polar latitudes. Major marine vertebrate groups include chondrichthyans (sharks, rays, chimaeras), bony fishes, marine reptiles, seabirds (petrels, albatrosses, sulids, gulls, terns and shags) and marine mammals. The numbers of species within each group occurring in Australia’s marine waters and numbers of nationally listed threatened species (and subspecies) under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) are summarised in Table 1. The total numbers of species are uncertain for some marine vertebrate groups, particularly marine Actinopterygii where a comprehensive list of species is not available for all Australian marine waters. -

Tube-Nosed Seabirds) Unique Characteristics

PELAGIC SEABIRDS OF THE CALIFORNIA CURRENT SYSTEM & CORDELL BANK NATIONAL MARINE SANCTUARY Written by Carol A. Keiper August, 2008 Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary protects an area of 529 square miles in one of the most productive offshore regions in North America. The sanctuary is located approximately 43 nautical miles northwest of the Golden Gate Bridge, and San Francisco California. The prominent feature of the Sanctuary is a submerged granite bank 4.5 miles wide and 9.5 miles long, which lay submerged 115 feet below the ocean’s surface. This unique undersea topography, in combination with the nutrient-rich ocean conditions created by the physical process of upwelling, produces a lush feeding ground. for countless invertebrates, fishes (over 180 species), marine mammals (over 25 species), and seabirds (over 60 species). The undersea oasis of the Cordell Bank and surrounding waters teems with life and provides food for hundreds of thousands of seabirds that travel from the Farallon Islands and the Point Reyes peninsula or have migrated thousands of miles from Alaska, Hawaii, Australia, New Zealand, and South America. Cordell Bank is also known as the albatross capital of the Northern Hemisphere because numerous species visit these waters. The US National Marine Sanctuaries are administered and managed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) who work with the public and other partners to balance human use and enjoyment with long-term conservation. There are four major orders of seabirds: 1) Sphenisciformes – penguins 2) *Procellariformes – albatross, fulmars, shearwaters, petrels 3) Pelecaniformes – pelicans, boobies, cormorants, frigate birds 4) *Charadriiformes - Gulls, Terns, & Alcids *Orders presented in this seminar In general, seabirds have life histories characterized by low productivity, delayed maturity, and relatively high adult survival. -

US Fish & Wildlife Service Seabird Conservation Plan—Pacific Region

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Seabird Conservation Plan Conservation Seabird Pacific Region U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Seabird Conservation Plan—Pacific Region 120 0’0"E 140 0’0"E 160 0’0"E 180 0’0" 160 0’0"W 140 0’0"W 120 0’0"W 100 0’0"W RUSSIA CANADA 0’0"N 0’0"N 50 50 WA CHINA US Fish and Wildlife Service Pacific Region OR ID AN NV JAP CA H A 0’0"N I W 0’0"N 30 S A 30 N L I ort I Main Hawaiian Islands Commonwealth of the hwe A stern A (see inset below) Northern Mariana Islands Haw N aiian Isla D N nds S P a c i f i c Wake Atoll S ND ANA O c e a n LA RI IS Johnston Atoll MA Guam L I 0’0"N 0’0"N N 10 10 Kingman Reef E Palmyra Atoll I S 160 0’0"W 158 0’0"W 156 0’0"W L Howland Island Equator A M a i n H a w a i i a n I s l a n d s Baker Island Jarvis N P H O E N I X D IN D Island Kauai S 0’0"N ONE 0’0"N I S L A N D S 22 SI 22 A PAPUA NEW Niihau Oahu GUINEA Molokai Maui 0’0"S Lanai 0’0"S 10 AMERICAN P a c i f i c 10 Kahoolawe SAMOA O c e a n Hawaii 0’0"N 0’0"N 20 FIJI 20 AUSTRALIA 0 200 Miles 0 2,000 ES - OTS/FR Miles September 2003 160 0’0"W 158 0’0"W 156 0’0"W (800) 244-WILD http://www.fws.gov Information U.S. -

LAYSAN ALBATROSS Phoebastria Immutabilis

Alaska Seabird Information Series LAYSAN ALBATROSS Phoebastria immutabilis Conservation Status ALASKA: High N. AMERICAN: High Concern GLOBAL: Vulnerable Breed Eggs Incubation Fledge Nest Feeding Behavior Diet Nov-July 1 ~ 65 d 165 d ground scrape surface dip fish, squid, fish eggs and waste Life History and Distribution Laysan Albatrosses (Phoebastria immutabilis) breed primarily in the Hawaiian Islands, but they inhabit Alaskan waters during the summer months to feed. They are the 6 most abundant of the three albatross species that visit 200 en Alaska. l The albatross has been described as the “true nomad ff Pok e of the oceans.” Once fledged, it remains at sea for three to J ht ig five years before returning to the island where it was born. r When birds are eight or nine years old they begin to breed. y The breeding season is November to July and the rest of Cop the year, the birds remain at sea. Strong, effortless flight is commonly seen in the southern Bering Sea, Aleutian the key to being able to spend so much time in the air. The Islands, and the northwestern Gulf of Alaska. albatross takes advantage of air currents just above the Nonbreeders may remain in Alaska throughout the year ocean's waves to soar in perpetual fluid motion. It may not and breeding birds are known to travel from Hawaii to flap its wings for hours, or even for days. The aerial Alaska in search of food for their young. Albatrosses master never touches land outside the breeding season, but have the ability to concentrate the food they catch and it does rest on the water to feed and sleep. -

18.4 Bacteria and Archaea Kingdom Eubacteria Domain Bacteria

18.4 Bacteria and Archaea Kingdom Eubacteria Domain Bacteria 18.4 Bacteria and Archaea Description Bacteria are single-celled prokaryotes. 18.4 Bacteria and Archaea Where do they live? Prokaryotes are widespread on Earth. ( Est. over 1 billion types of bacteria, and over 1030 individual prokaryote cells on earth.) Found in all land and ocean environments, even inside other organisms! 18.4 Bacteria and Archaea Common Examples • E. Coli • Tetanus bacteria • Salmonella bacteria • Tuberculosis bacteria • Staphylococcus • Streptococcus 18.4 Bacteria and Archaea Modes Of Nutrition • Bacteria may be heterotrophs or autotrophs 18.4 Bacteria and Archaea Bacteria Reproduce How? • by binary fission. • exchange genes during conjugation= conjugation bridge increases diversity. • May survive by forming endospores = specialized cell with thick protective cell wall. TEM; magnification 6000x • Can survive for centuries until environment improves. Have been found in mummies! 18.4 Bacteria and Archaea • Bacteria Diagram – plasmid = small piece of genetic material, can replicate independently of the chromosome – flagellum = different than in eukaryotes, but for movement – pili = used to stick the bacteria to eachpili other or surfaces plasma membrance flagellum chromosome cell wall plasmid This diagram shows the typical structure of a prokaryote. Archaea and bacteria look very similar, although they have important molecular differences. 18.4 Bacteria and Archaea • Classified by: their need for oxygen, how they gram stain, and their shapes 18.4 Bacteria and Archaea Main Groups by Shapes – rod-shaped, called bacilli – spiral, called spirilla or spirochetes – spherical, called cocci Spirochaeta: spiral Lactobacilli: rod-shaped Enterococci: spherical 18.4 Bacteria and Archaea • Main Groups by their need for oxygen. -

Sexual Segregation in Marine Fish, Reptiles, Birds and Mammals: Behaviour Patterns, Mechanisms and Conservation Implications

Author's personal copy CHAPTER TWO Sexual Segregation in Marine Fish, Reptiles, Birds and Mammals: Behaviour Patterns, Mechanisms and Conservation Implications Victoria J. Wearmouth* and David W. Sims,† * Contents 1. Introduction 108 2. Types of Sexual Segregation 110 2.1. Habitat versus social segregation 110 2.2. Detecting types of sexual segregation 112 2.3. Measurement problems for marine species 113 3. Sexual Segregation in Marine Vertebrates 116 3.1. Sexual segregation in marine mammals 116 3.2. Sexual segregation in marine birds 122 3.3. Sexual segregation in marine reptiles 126 3.4. Sexual segregation in marine fish 128 4. Mechanisms Underlying Sexual Segregation: Hypotheses 134 4.1. Predation-risk hypothesis (reproductive strategy hypothesis) 134 4.2. Forage selection hypothesis (sexual dimorphism—body-size hypothesis) incorporating the scramble competition and incisor breadth hypotheses 138 4.3. Activity budget hypothesis (body-size dimorphism hypothesis) 141 4.4. Thermal niche–fecundity hypothesis 145 4.5. Social factors hypothesis (social preference and social avoidance hypotheses) 146 5. Sexual Segregation in Catshark: A Case Study 148 6. Conservation Implications of Sexual Segregation 152 7. A Synthesis and Future Directions for Research 156 Acknowledgements 160 References 160 * Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, The Laboratory, Citadel Hill, Plymouth PL1 2PB, United Kingdom { Marine Biology and Ecology Research Centre, School of Biological Sciences, University of Plymouth, Drake Circus, Plymouth PL4 8AA, United Kingdom Advances in Marine Biology, Volume 54 # 2008 Elsevier Ltd. ISSN 0065-2881, DOI: 10.1016/S0065-2881(08)00002-3 All rights reserved. 107 Author's personal copy 108 Victoria J. -

“Poop, Roots, and Deadfall: the Story of Blue Carbon”

“Poop, Roots, and Deadfall: The Story of Blue Carbon” Mark J. Spalding, President of The Ocean Foundation “ Poop, Roots, and Deadfall: The Story of Blue Carbon” Why Blue Carbon? • Blue carbon offers a win/win/win • It allows for collaborative multi-stakeholder engagement in climate change adaptation and mitigation “ Poop, Roots, and Deadfall: The Story of Blue Carbon” The Ocean and Carbon “ Poop, Roots, and Deadfall: The Story of Blue Carbon” • The ocean is by far the largest carbon sink in the world • It removes 20-35% of atmospheric carbon emissions • Biological life in the ocean captures and stores 93% of the earth’s carbon dioxide • It has been estimated that biological life in the high seas capture and store 1.5 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide per year “ Poop, Roots, and Deadfall: The Story of Blue Carbon” What is Blue Carbon? Christiaan Triebert “ Poop, Roots, and Deadfall: The Story of Blue Carbon” Blue Carbon is the ability of tidal wetlands, seagrass habitats, and other marine organisms to take up carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases from the atmosphere, and store them helping to mitigate the effects of climate change. “ Poop, Roots, and Deadfall: The Story of Blue Carbon” • Carbon Sequestration – The process of capturing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, measured as a rate of carbon uptake per year • Carbon Storage – the long-term confinement of carbon in plant materials or sediment, measured as a total weight of carbon stored “ Poop, Roots, and Deadfall: The Story of Blue Carbon” Carbon Stored and Sequestered By Coastal Wetlands • Carbon is held in the above and below ground plant matter and within wetland soils and seafloor sediments. -

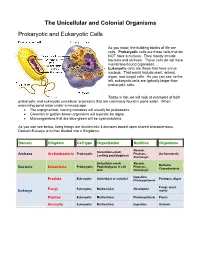

The Unicellular and Colonial Organisms Prokaryotic And

The Unicellular and Colonial Organisms Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells As you know, the building blocks of life are cells. Prokaryotic cells are those cells that do NOT have a nucleus. They mostly include bacteria and archaea. These cells do not have membrane-bound organelles. Eukaryotic cells are those that have a true nucleus. That would include plant, animal, algae, and fungal cells. As you can see, to the left, eukaryotic cells are typically larger than prokaryotic cells. Today in lab, we will look at examples of both prokaryotic and eukaryotic unicellular organisms that are commonly found in pond water. When examining pond water under a microscope… The unpigmented, moving microbes will usually be protozoans. Greenish or golden-brown organisms will typically be algae. Microorganisms that are blue-green will be cyanobacteria. As you can see below, living things are divided into 3 domains based upon shared characteristics. Domain Eukarya is further divided into 4 Kingdoms. Domain Kingdom Cell type Organization Nutrition Organisms Absorb, Unicellular-small; Prokaryotic Photsyn., Archaeacteria Archaea Archaebacteria Lacking peptidoglycan Chemosyn. Unicellular-small; Absorb, Bacteria, Prokaryotic Peptidoglycan in cell Photsyn., Bacteria Eubacteria Cyanobacteria wall Chemosyn. Ingestion, Eukaryotic Unicellular or colonial Protozoa, Algae Protista Photosynthesis Fungi, yeast, Fungi Eukaryotic Multicellular Absorption Eukarya molds Plantae Eukaryotic Multicellular Photosynthesis Plants Animalia Eukaryotic Multicellular Ingestion Animals Prokaryotic Organisms – the archaea, non-photosynthetic bacteria, and cyanobacteria Archaea - Microorganisms that resemble bacteria, but are different from them in certain aspects. Archaea cell walls do not include the macromolecule peptidoglycan, which is always found in the cell walls of bacteria. Archaea usually live in extreme, often very hot or salty environments, such as hot mineral springs or deep-sea hydrothermal vents. -

Seabird Protection & Avoidance Tips

Seabird Protection & Avoidance Tips Seabirds live in a variety of habitats in and around shallow water and coastal environments. They represent a vital part of marine ecology and are protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. In fact, most of the 312 species of seabirds you may encounter while fishing are likely to be protected by law, with some classified as endangered or threatened under the Endangered Species Act. NOAA Depending on the geographic region, fishermen in the U.S. can FISHERIES observe species of Albatross, Cormorants, Gannet, Loons, Pelicans, Puffins, Sea Gulls, Storm-Petrels, Shearwaters, and SERVICE Terns, among others. Office of Sustainable Fisheries Be Aware of Seabird Behavior Seabirds feed on smaller fish that most anglers use for bait, so they typically won’t challenge a fisherman for his catch, however, the seabird’s hunting methods still put them in danger of getting hooked or entangled in a fisherman’s line. Many seabirds feed on krill, fish, squid or other prey items at the ocean's surface, while some, such as Cormorants, are known to dive to depths of more than 100 ft below the waves to catch a fish. In another technique, seabirds in flight will “plunge dive” into the water in pursuit of a fast-moving fish. Brown Pelicans, for example, can make vertical dives from more than 70 feet above the water when chasing their prey. Young seabirds, especially young pelicans, are particularly susceptible to being ensnared by fishing line. What If I Accidentally Hook a Seabird? HOW CAN I HELP SEABIRDS? In the unfortunate event of a hooked seabird, don't cut or break the line. -

Arctic Marine Biodiversity

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292115665 Arctic marine biodiversity CHAPTER · JANUARY 2016 READS 142 12 AUTHORS, INCLUDING: Lis Lindal Jørgensen Philippe Archambault Institute of Marine Research in Norway Université du Québec à Rimouski UQAR 36 PUBLICATIONS 285 CITATIONS 137 PUBLICATIONS 1,574 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Dieter Piepenburg Jake Rice Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel Fisheries and Oceans Canada 71 PUBLICATIONS 1,705 CITATIONS 67 PUBLICATIONS 2,279 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE All in-text references underlined in blue are linked to publications on ResearchGate, Available from: Andrey V. Dolgov letting you access and read them immediately. Retrieved on: 19 February 2016 Chapter 36G. Arctic Ocean Contributors: Lis Lindal Jørgensen, Philippe Archambault, Claire Armstrong, Andrey Dolgov, Evan Edinger, Tony Gaston, Jon Hildebrand, Dieter Piepenburg, Walker Smith, Cecilie von Quillfeldt, Michael Vecchione, Jake Rice (Lead member) Referees: Arne Bjørge, Charles Hannah. 1. Introduction 1.1 State The Central Arctic Ocean and the marginal seas such as the Chukchi, East Siberian, Laptev, Kara, White, Greenland, Beaufort, and Bering Seas, Baffin Bay and the Canadian Archipelago (Figure 1) are among the least-known basins and bodies of water in the world ocean, because of their remoteness, hostile weather, and the multi-year (i.e., perennial) or seasonal ice cover. Even the well-studied Barents and Norwegian Seas are partly ice covered during winter and information during this period is sparse or lacking. The Arctic has warmed at twice the global rate, with sea- ice loss accelerating (Figure 2, ACIA, 2004; Stroeve et al., 2012, Chapter 46 in this report), especially along the coasts of Russia, Alaska, and the Canadian Archipelago (Post et al., 2013).