The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

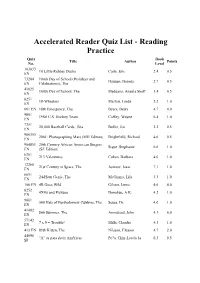

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. Level 103833 10 Little Rubber Ducks Carle, Eric 2.4 0.5 EN 73204 100th Day of School (Holidays and Haugen, Brenda 2.7 0.5 EN Celebrations), The 41025 100th Day of School, The Medearis, Angela Shelf 1.4 0.5 EN 8251 18-Wheelers Maifair, Linda 5.2 1.0 EN 661 EN 18th Emergency, The Byars, Betsy 4.7 4.0 9801 1980 U.S. Hockey Team Coffey, Wayne 6.4 1.0 EN 7351 20,000 Baseball Cards...Sea Buller, Jon 2.5 0.5 EN 900355 2061: Photographing Mars (MH Edition) Brightfield, Richard 4.6 0.5 EN 904851 20th Century African American Singers Sigue, Stephanie 6.6 1.0 EN (SF Edition) 6201 213 Valentines Cohen, Barbara 4.0 1.0 EN 12260 21st Century in Space, The Asimov, Isaac 7.1 1.0 EN 6651 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila 3.3 1.0 EN 166 EN 4B Goes Wild Gilson, Jamie 4.6 4.0 8252 4X4's and Pickups Donahue, A.K. 4.2 1.0 EN 9001 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, The Seuss, Dr. 4.0 1.0 EN 41482 $66 Summer, The Armistead, John 4.3 6.0 EN 57142 7 x 9 = Trouble! Mills, Claudia 4.3 1.0 EN 413 EN 89th Kitten, The Nilsson, Eleanor 4.7 2.0 44096 "A" es para decir Am?ricas Pe?a, Chin-Lee/de la 6.3 0.5 SP Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. -

Mdms Fraser List of Works E.Docx

Andrea Fraser List of Works This list of works aims to be comprehensive, and works are listed chronologically. A single asterisk beside the title (*) indicates that an installation or project is represented in the exhibition only as documentation. Two asterisks (**) indicate that a work is not included in the exhibition. The context of a performance or work (for example commission, project, or exhibition) is listed after the medium. When no other performer is listed, the artist performed the work alone. When no other location is listed, videotapes document the original performance. Unless otherwise specified, videotapes are standard definition. If no other language is indicated, texts, performances, and videos are in English. Dates of performances are noted where possible. Dimensions are given as height x width x depth. Collection credits have been listed for series up to editions of three and public collections have been listed for editions of four to eight. Unless otherwise specified, exhibited works are on loan from the artist. Woman 1/ Madonna and Child 1506–1967 , 1984 Artist’s book Offset print, 16 pages 8 5/8 x 10 1/16 in. (22 x 25.5 cm) Edition: 500 Untitled (Pollock/Titian) #1 , 1984/2005 (**) Digital chromogenic color print 26 3/4 x 60 in. (67.9 x 152.4 cm) Edition: 5 + 1 AP Untitled (Pollock/Titian) #2, 1984/2005 (**) Digital chromogenic color print 27 x 60 in. (68.6 x 152.4 cm) Edition: 5 + 1 AP Untitled (Pollock/Titian) #3 , 1984/2005 (**) Digital chromogenic color print 40 x 60 in. (101.6 x 152.4 cm) Edition: 5 + 1 AP Untitled (Pollock/Titian) #4 , 1984/2005 (**) Digital chromogenic color print 40 x 61 in, (101.6 x 154.94 cm) Edition: 5 + 1 AP 1/5 Kemper Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO Untitled (de Kooning/Raphael) #1 , 1984/2005 (**) Digital chromogenic color print 40 x 30 in. -

High Performance Magazine Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt5p30369v Online items available Finding aid for the magazine records, 1953-2005 Finding aid for the magazine 2006.M.8 1 records, 1953-2005 Descriptive Summary Title: High Performance magazine records Date (inclusive): 1953-2005 Number: 2006.M.8 Creator/Collector: High Performance Physical Description: 216.1 Linear Feet(318 boxes, 29 flatfile folders, 1 roll) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: High Performance magazine records document the publication's content, editorial process and administrative history during its quarterly run from 1978-1997. Founded as a magazine covering performance art, the publication gradually shifted editorial focus first to include all new and experimental art, and then to activism and community-based art. Due to its extensive compilation of artist files, the archive provides comprehensive documentation of the progressive art world from the late 1970s to the late 1990s. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical/Historical Note Linda Burnham, a public relations officer at University of California, Irvine, borrowed $2,000 from the university credit union in 1977, and in a move she described as "impulsive," started High -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

Cartographic Perspectives Information Society 1

Number 53, Winterjournal 2006 of the Northcartographic American Cartographic perspectives Information Society 1 cartographic perspectives Number 53, Winter 2006 in this issue Letter from the Editor INTRODUCTION Art and Mapping: An Introduction 4 Denis Cosgrove Dear Members of NACIS, FEATURED ARTICLES Welcome to CP53, the first issue of Map Art 5 Cartographic Perspectives in 2006. I Denis Wood plan to be brief with my column as there is plenty to read on the fol- Interpreting Map Art with a Perspective Learned from 15 lowing pages. This is an important J.M. Blaut issue on Art and Cartography that Dalia Varanka was spearheaded about a year ago by Denis Wood and John Krygier. Art-Machines, Body-Ovens and Map-Recipes: Entries for a 24 It’s importance lies in the fact that Psychogeographic Dictionary nothing like this has ever been kanarinka published in an academic journal. Ever. To punctuate it’s importance, Jake Barton’s Performance Maps: An Essay 41 let me share a view of one of the John Krygier reviewers of this volume: CARTOGRAPHIC TECHNIQUES …publish these articles. Nothing Cartographic Design on Maine’s Appalachian Trail 51 more, nothing less. Publish them. Michael Hermann and Eugene Carpentier III They are exciting. They are interest- ing: they stimulate thought! …They CARTOGRAPHIC COLLECTIONS are the first essays I’ve read (other Illinois Historical Aerial Photography Digital Archive Keeps 56 than exhibition catalogs) that actu- Growing ally try — and succeed — to come to Arlyn Booth and Tom Huber terms with the intersections of maps and art, that replace the old formula REVIEWS of maps in/as art, art in/as maps by Historical Atlas of Central America 58 Reviewed by Mary L. -

Detailed Reporting from Closing Survey (English)

Detailed Reporting from Closing Survey (English) Index Ship 1 Embodied/Thoughts 24 Beings 52 Past Experiences 62 Ship ● I saw colored lights behind Mark during the meditation. Also, a round moving light behind him. - Austin, Texas, USA ● I saw a little moving green and orange double-helix on the screen of the live-stream from the Day 10 culminating meditation (that’s actually the only part I ended up participating in). - Austin, Texas, USA ● I had my eyes open during the livestream, watching Mark and the sky on TV. I saw a definite revolving rainbow to Mark’s right in the sky about five minutes into the stream. If you video copied it look. - Waimea, Hawaii, USA ● Lights in the sky. - Lake Shore, Minnesota, USA ● I dreamed last night that I watched a ship being attacked by smaller vessels over the city. The ship was hit critically and fell into the ocean and caused a tidal wave. Then something in my room was knocked off of my dresser and woke me suddenly. - Carlsbad, California, USA ● I saw some amber lights that faded in the sky, they didn’t look like airplanes. - Coconut Creek, Florida ● We had a sighting on Sunday night. - Dallas,TX ● Beautiful Light Beings playing on the surface of the ocean. Two in particular last night that were green. - Oceanside, California, USA ● I saw a blinking light like from an aeroplane, but at random intervals it got really bright. - Lovelock, Nevada, USA ● A bright object flashed and moved about 6 times and changed colors. - Salt Lake City, Utah, USA ● We did our CE5 meditation on Monday, July 13th at 9 PM and as we were looking up to the sky during the quiet time after the meditation, we saw a bright, white-light orb appear from the south coming past Altair/Aquila and then it suddenly turned and went East. -

Daily Eastern News: March 28, 2003 Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep March 2003 3-28-2003 Daily Eastern News: March 28, 2003 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2003_mar Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: March 28, 2003" (2003). March. 14. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2003_mar/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 2003 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in March by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Thll the troth March28,2003 + FRIDAY and don't be afraid. • VO LUME 87 . NUMBER 123 THE DA ILYEASTERN NEWS . COM THE DAILY Four for 400 Eastern baseball team has four chances this weekend to earn head coach Jim EASTERN NEWS <:rlh....,,t n his 400th career Student fees may be hiked • Fees may raise $70 next semester By Avian Carrasquillo STUDENT GOVERNMENT ED ITOR If approved students can expect to pay an extra $70.55 in fees per semester. The Student Senate Thition and Fee Review Committee met Thursday to make its final vote on student fees for next year. Following the committee's approval, the fee proposals must be approved by the Student Senate, vice president for student affairs, the President's Council and Eastern's Board of Trustees. The largest increase of the fees will come in the network fee, which will increase to $48 per semester to fund a 10-year network improvement project. The project, which could break ground as early as this summer would upgrade the campus infra structure for network upgrades, which will Tom Akers, head coach of Eastern's track and field team, watches high jumpers during practice Thursday afternoon. -

The Art of Duplicitous Ingemination

Originally published in ALLAN McCOLLUM Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum Eindhoven, Holland; 1989 Allan McCollum: The Art of Duplicitous Ingemination LYNNE COOKE ‘THE QUESTION OF NUANCE (within unity) is linked to the model, while difference (within uniformity) is linked with mass-production. Nuances are infinite, they are an inflexion, renewed continually by invention within a free syntax. Differences are finite in number and result from the systematic bending of a paradigm. We must not make a mistake here: if nuance seems rare and the marginal difference unquantifiable, because it benefits from being diffused widely, structurally it is still only the nuance which is inexhaustible. (In this way the model is linked to the work of art). The serial difference returns into a finite combination, into a system which changes continually according to fashion but which, for each synchronic moment in which it is considered, is limited and narrowly restricted by the dictates of production. When all is said Allan McCollum. Over Ten Thousand and done, a limited range of objects is offered to the vast Individual Works (detail). 1987-88. majority through the series, while a tiny minority is Enamel on cast Hydrocal, 2” diameter each, lengths variable. presented with an infinite variation of models. The first social group is offered a repertoire (however vast) of fixed elements, while the latter is given a multiplicity of opportunities (the former is given an indexed code of values, the latter a continually new invention). The question of class is therefore fundamental to this whole business. Through the redundancy of its secondary characteristics, the serial object makes up for the loss of its fundamental qualities. -

Using Te Reo Māori and Ta Re Moriori in Taxonomy

VealeNew Zealand et al.: Te Journal reo Ma- oriof Ecologyin taxonomy (2019) 43(3): 3388 © 2019 New Zealand Ecological Society. 1 REVIEW Using te reo Māori and ta re Moriori in taxonomy Andrew J. Veale1,2* , Peter de Lange1 , Thomas R. Buckley2,3 , Mana Cracknell4, Holden Hohaia2, Katharina Parry5 , Kamera Raharaha-Nehemia6, Kiri Reihana2 , Dave Seldon2,3 , Katarina Tawiri2 and Leilani Walker7 1Unitec Institute of Technology, 139 Carrington Road, Mt Albert, Auckland 1025, New Zealand 2Manaaki Whenua - Landcare Research, 231 Morrin Road, St Johns, Auckland 1072, New Zealand 3School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland, 3A Symonds St, Auckland CBD, Auckland 1010, New Zealand 4Rongomaiwhenua-Moriori, Kaiangaroa, Chatham Island, New Zealand 5Massey University, Private Bag 11222 Palmerston North, 4442, New Zealand 6Ngāti Kuri, Otaipango, Ngataki, Te Aupouri, Northland, New Zealand 7Auckland University of Technology, 55 Wellesley St E, Auckland CBS, Auckland 1010, New Zealand *Author for correspondence (Email: [email protected]) Published online: 28 November 2019 Auheke: Ko ngā ingoa Linnaean ka noho hei pou mō te pārongo e pā ana ki ngā momo koiora. He mea nui rawa kia mārama, kia ahurei hoki ngā ingoa pūnaha whakarōpū. Me pēnei kia taea ai te whakawhitiwhiti kōrero ā-pūtaiao nei. Nā tēnā kua āta whakatakotohia ētahi ture, tohu ārahi hoki hei whakahaere i ngā whakamārama pūnaha whakarōpū. Kua whakamanahia ēnei kia noho hei tikanga mō te ao pūnaha whakarōpū. Heoi, arā noa atu ngā hua o te tukanga waihanga ingoa Linnaean mō ngā momo koiora i tua atu i te tautohu noa i ngā momo koiora. Ko tētahi o aua hua ko te whakarau: (1) i te mātauranga o ngā iwi takatake, (2) i te kōrero rānei mai i te iwi o te rohe, (3) i ngā kōrero pūrākau rānei mō te wāhi whenua. -

Press Release

Press Release April 2013 Brooklyn Museum’s Annual Gala “The Brooklyn Artists Ball” and After-Party Celebrates Brooklyn’s Creative Community Museum to Honor Trustee Barbara Knowles Debs and Artists Vik Muniz, Wangechi Mutu, and Roxy Paine Table Environments by Brooklyn Artists to Provide Guests with Multisensory Dining Experience On Wednesday evening, April 24, 2013, the Brooklyn Museum will host its annual fundraising gala, the Brooklyn Artists Ball, celebrating Brooklyn’s creative community. This year’s event will commence at 6:30 p.m. with cocktails and hors d’oeuvres in the Martha A. and Robert S. Rubin Glass Pavilion. Following the cocktail reception, a seated dinner featuring cuisine by Food in Motion will take place in the Museum’s magnificent Beaux-Arts Court. Guests will dine at table environments created for the occasion by eighteen Brooklyn artists: Njideka Akunyili, Daniel Arsham, Jules de Balincourt, FAILE, Jennifer Catron and Paul Outlaw, Joey Frank, Jacob Hashimoto, Steven and William Ladd, Emily Noelle Lambert, Fernando Mastrangelo, Navin June Norling, José Parlá, Analia Segal, Alison Elizabeth Taylor, Max Toth, and Lan Tuazon. Each artist will transform a 40-foot-long table into a specially created work of art that will be on view for one night only. Immediately following the Ball at 9 p.m., the Museum will host an After-Party that includes dessert and dancing amid an installation created especially for the event by artist Luis Gispert and music by DJs Atlanta De Cadenet Taylor and Andrew Andrew. Vanity Projects, a new art gallery-cum- nail salon, will also be participating in the evening by creating nail designs for guests based on the table installations. -

A Celebration of the Brooklyn Museum Works by Contemporary Artists to Be Sold at Christie’S New York to Benefit the Brooklyn Museum

PRESS RELEASE | NEW YORK | 20 FEBRUARY 2013 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE A CELEBRATION OF THE BROOKLYN MUSEUM WORKS BY CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS TO BE SOLD AT CHRISTIE’S NEW YORK TO BENEFIT THE BROOKLYN MUSEUM YINKA SHONIBARE (B. 1962) Girl on Globe Executed in 2013. Estimate: $60,000-80,000 New York - Christie's is honored to offer 23 exceptional contemporary works, donated by the artists to benefit the artistic activities of the Brooklyn Museum. Proceeds from the sale will support the museum's dynamic program of special exhibitions, presentation of its world-renowned holdings, and its extensive public programs. The works will be sold during the First Open Sale of Post-War and Contemporary Art on March 8, 2013. "The Board of Trustees of the Brooklyn Museum and I would like to express our gratitude to the twenty-two artists for their generous gifts of wonderful works of art. We would also like to thank Christie's for their ongoing support of the Brooklyn Museum. Following the sale of four major works in November, Christie's has remained committed to one of New York City's great cultural institutions with its forthcoming and exciting BKLYN auction in March," said Arnold L. Lehman, Director of the Brooklyn Museum The auction will present works by Rina Banerjee, Matthew Barney, Sanford Biggers, E.V. Day, Aleksandar Duravcevic, Valerie Hegarty, Michael Joo, Byron Kim, Jemima Kirke, Joseph Kosuth, Adam McEwen, Vik Muniz, Wangechi Mutu, Angel Otero, Jean-Michel Othoniel, Roxy Paine, Julian Schnabel, Yinka Shonibare, Swoon, The Bruce High Quality Foundation, Kehinde Wiley and Dustin Yellin. -

Why Mammals Are Called Mammals: Gender Politics in Eighteenth-Century Natural History Author(S): Londa Schiebinger Source: the American Historical Review, Vol

Why Mammals are Called Mammals: Gender Politics in Eighteenth-Century Natural History Author(s): Londa Schiebinger Source: The American Historical Review, Vol. 98, No. 2 (Apr., 1993), pp. 382-411 Published by: American Historical Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2166840 Accessed: 22/01/2010 10:27 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=aha. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. American Historical Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The American Historical Review. http://www.jstor.org Why Mammals Are Called Mammals: Gender Politics in Eighteenth-Century Natural History LONDA SCHIEBINGER IN 1758, IN THE TENTH EDITION OF HIS Systema naturae, Carolus Linnaeus introduced the term Mammaliainto zoological taxonomy.