Why Mammals Are Called Mammals: Gender Politics in Eighteenth-Century Natural History Author(S): Londa Schiebinger Source: the American Historical Review, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Race and Membership in American History: the Eugenics Movement

Race and Membership in American History: The Eugenics Movement Facing History and Ourselves National Foundation, Inc. Brookline, Massachusetts Eugenicstextfinal.qxp 11/6/2006 10:05 AM Page 2 For permission to reproduce the following photographs, posters, and charts in this book, grateful acknowledgement is made to the following: Cover: “Mixed Types of Uncivilized Peoples” from Truman State University. (Image #1028 from Cold Spring Harbor Eugenics Archive, http://www.eugenics archive.org/eugenics/). Fitter Family Contest winners, Kansas State Fair, from American Philosophical Society (image #94 at http://www.amphilsoc.org/ library/guides/eugenics.htm). Ellis Island image from the Library of Congress. Petrus Camper’s illustration of “facial angles” from The Works of the Late Professor Camper by Thomas Cogan, M.D., London: Dilly, 1794. Inside: p. 45: The Works of the Late Professor Camper by Thomas Cogan, M.D., London: Dilly, 1794. 51: “Observations on the Size of the Brain in Various Races and Families of Man” by Samuel Morton. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences, vol. 4, 1849. 74: The American Philosophical Society. 77: Heredity in Relation to Eugenics, Charles Davenport. New York: Henry Holt &Co., 1911. 99: Special Collections and Preservation Division, Chicago Public Library. 116: The Missouri Historical Society. 119: The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, 1882; John Singer Sargent, American (1856-1925). Oil on canvas; 87 3/8 x 87 5/8 in. (221.9 x 222.6 cm.). Gift of Mary Louisa Boit, Julia Overing Boit, Jane Hubbard Boit, and Florence D. Boit in memory of their father, Edward Darley Boit, 19.124. -

The Scientist from a Flourishing Sex-Life to Modern DNA Technology

The Scientist From a Flourishing Sex-life to Modern DNA Technology Linnaeus the Scientist ll of a sudden you are standing there, in the bo- tanic garden that is to be Linnaeus’s base for a whole lifetime of scientific achievements. It is a beautiful spring day in Uppsala, the sun’s rays warm your heart as cheerfully as in your own 21st century. The hus- tle and bustle of the town around you break into the cen- trally located garden. Carriage wheels rattle over the cob- blestones, horses neigh, hens cackle from the house yards. The acrid smell of manure and privies bears witness to a town atmosphere very different from your own. You cast a glance at what is growing in the garden. The beds do not look particularly well kept. In fact, the whole garden gives a somewhat dilapidated impression. Suddenly, in the distance, you see a young man squat- A ting down by one of the beds. He is looking with great concentration at a small flower, examining it closely through a magnifying glass. When he lifts his head for a moment and ponders, you recognise him at once. It is Carl von Linné, or Carl Linnaeus as he was originally called. He looks very young, just over 20 years old. His pale cheeks tell you that it has been a harsh winter. His first year as a university student at Uppsala has been marked by a lack of money for both food and clothes as well as for wood to warm his rented room. 26 linnaean lessons • www.bioresurs.uu.se © 2007 Swedish Centre for School Biology and Biotechnology, Uppsala University, Sweden. -

Of Dahlia Myths.Pub

Cavanilles’ detailed illustrations established the dahlia in the botanical taxonomy In 1796, the third volume of “Icones” introduced two more dahlia species, named D. coccinea and D. rosea. They also were initially thought to be sunflowers and had been brought to Spain as part of the Alejandro Malaspina/Luis Neé expedition. More than 600 drawings brought the plant collection to light. Cavanilles, whose extensive correspondence included many of Europe’s leading botanists, began to develop a following far greater than his title of “sacerdote” (priest, in French Abbé) ever would have offered. The A. J. Cavanilles archives of the present‐day Royal Botanical Garden hold the botanist’s sizable oeu‐ vre, along with moren tha 1,300 letters, many dissertations, studies, and drawings. In time, Cavanilles achieved another goal: in 1801, he was finally appointed professor and director of the garden. Regrettably, he died in Madrid on May 10, 1804. The Cavanillesia, a tree from Central America, was later named for this famousMaterial Spanish scientist. ANDERS DAHL The lives of Dahl and his Spanish ‘godfather’ could not have been any more different. Born March 17,1751, in Varnhem town (Västergötland), this Swedish botanist struggled with health and financial hardship throughout his short life. While attending school in Skara, he and several teenage friends with scientific bent founded the “Swedish Topographic Society of Skara” and sought to catalogue the natural world of their community. With his preacher father’s support, the young Dahl enrolled on April 3, 1770, at Uppsala University in medicine, and he soon became one of Carl Linnaeus’ students. -

Instr Uct Or's Guide Science

Scientists Of The Past SCIENCE Lesson Objectives • Students will compare and contrast how the rules of society restricted the progress of science in the past. • Students will list several famous scientists from history. Activities Checklist In this lesson, the student will • Watch the instructional video about how the rules of society restricted the progress of science in the past and the scientists who, over time, were able to break away from these restrictions • Interact with My Book and learn about how the rules of society restricted the progress of science in the past • Complete the crossword puzzle, in the Science Activities Workbook, by determining the scientist who made each cited discovery • Complete all learning activities assessing understanding of the sequence of scientifi c events and discoveries Video Summary Students are given a modern-day scenario of reading something aloud in front of the classroom to better understand the stress scientists felt during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when they were presenting new scientifi c theories to society. Scientists of the past were not always respected. Sometimes publicly voicing their scientifi c opinions could result in jail, exile, or even death. Religion determined what could or could not be accepted as explanations and discoveries. When a scientist would come up with a new explanation for why something occurred in nature, he or she would often have to argue the claim against the church -- and the church always won. After many, many years, the scientifi c community was able to break away from the church, resulting in numerous scientifi c endeavors. Some of the most famous scientists include Anton van Leeuwenhoek (improved the microscope), Carl Linnaeus (developed the classifi cation of life on Earth), Charles Darwin (developed the Theory of Evolution by Natural Selection), and Albert Einstein (worked within mathematics, GUIDE INSTRUCTOR’S physics, and astronomy). -

The Voc and Swedish Natural History. the Transmission of Scientific Knowledge in the Eighteenth Century

THE VOC AND SWEDISH NATURAL HISTORY. THE TRANSMISSION OF SCIENTIFIC KNOWLEDGE IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY Christina Skott In the later part of the eighteenth century Sweden held a place as one of the foremost nations in the European world of science. This was mainly due to the fame of Carl Linnaeus (1707–78, in 1762 enno- bled von Linné), whose ground breaking new system for classifying the natural world created a uniform system of scientific nomenclature that would be adopted by scientists all over Europe by the end of the century. Linnaeus had first proposed his new method of classifying plants in the slim volume Systema Naturae, published in 1735, while he was working and studying in Holland. There, he could for the first time himself examine the flora of the Indies: living plants brought in and cultivated in Dutch gardens and greenhouses as well as exotic her- baria collected by employees of the VOC. After returning to his native Sweden in 1737 Linnaeus would not leave his native country again. But, throughout his lifetime, Systema Naturae would appear in numerous augmented editions, each one describing new East Indian plants and animals. The Linnean project of mapping the natural world was driven by a strong patriotic ethos, and Linneaus would rely heavily on Swed- ish scientists and amateur collectors employed by the Swedish East India Company; but the links to the Dutch were never severed, and he maintained extensive contacts with leading Dutch scientists through- out his life. Linnaeus’ Dutch connections meant that his own students would become associated with the VOC. -

Linnaeus at Home

NATURE-BASED ACTIVITIES FOR PARENTS LINNAEUS 1 AT HOME A GuiDE TO EXPLORING NATURE WITH CHILDREN Acknowledgements Written by Joe Burton Inspired by Carl Linnaeus With thanks to editors and reviewers: LINNAEUS Lyn Baber, Melissa Balzano, Jane Banham, Sarah Black, Isabelle Charmantier, Mark Chase, Maarten Christenhusz, Alex Davey, Gareth Dauley, AT HOME Zia Forrai, Jon Hale, Simon Hiscock, Alice ter Meulen, Lynn Parker, Elizabeth Rollinson, James Rosindell, Daryl Stenvoll-Wells, Ross Ziegelmeier Share your explorations @LinneanLearning #LinnaeusAtHome Facing page: Carl Linnaeus paper doll, illustrated in 1953. © Linnean Society of London 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrival system or trasmitted in any form or by any means without the prior consent of the copyright owner. www.linnean.org/learning “If you do not know Introduction the names of things, the knowledge of them is Who was Carl Linnaeus? Contents Pitfall traps 5 lost too” Carl Linnaeus was one of the most influential scientists in the world, - Carl Linnaeus A bust of ‘The Young Linnaeus’ by but you might not know a lot about him. Thanks to Linnaeus, we Bug hunting 9 Anthony Smith (2007). have a naming system for all species so that we can understand how different species are related and can start to learn about the origins Plant hunting 13 of life on Earth. Pond dipping 17 As a young man, Linnaeus would study the animals, plants, Bird feeders 21 minerals and habitats around him. By watching the natural world, he began to understand that all living things are adapted to their Squirrel feeders 25 environments and that they can be grouped together by their characteristics (like animals with backbones, or plants that produce Friendly spaces 29 spores). -

“The Infinite Universe of the New Cosmology, Infinite in Duration As Well As Exten- Sion, in Which Eternal Matter in Accordanc

“The infinite Universe of the New Cosmology, infinite in Duration as well as Exten- sion, in which eternal matter in accordance with eternal and necessary laws moves endlessly and aimlessly in eternal space, inherited all the ontological attributes of Divinity. Yet only those — all the others the departed God took with him... The Divine Artifex had therefore less and less to do in the world. He did not even have to con- serve it, as the world, more and more, became able to dispense with this service...” ALEXANDRE KOYRE, “From the Closed World to the Infinite Universe”, 1957 into the big world -26- “La raison pour laquelle la relocalisation du global est devenue si importante est que le Terre elle-même pourrait bien ne pas être un globe après tout (...). Même la fameuse vision de la “planète bleue” pour- rait se révéler comme une image composite, c’est à dire une image composée de l’ancienne forme donnée au Dieu chrétien et du réseau complexe d’acquisitions de données de la NASA, à son tour projeté à l’intérieur du panorama diffracté des médias. Voilà peut-être la source de la fascination que l’image de la sphère a exercé depuis: la forme sphérique arrondit la con- naissance en un volume continu, complet, transparent, omniprésent qui masque la tâche extraordinairement difficile d’assembler les points de données venant de tous les instruments et de toutes les disciplines. Une sphère n’a pas d’histoire, pas de commencement, pas de fin, pas de trou, pas de discontinuité d’aucune sorte.” BRUNO LATOUR, “l’Anthropocène et la Destruction de l’Image -

Statutes and Rules for the British Museum

(ft .-3, (*y Of A 8RI A- \ Natural History Museum Library STATUTES AND RULES BRITISH MUSEUM STATUTES AND RULES FOR THE BRITISH MUSEUM MADE BY THE TRUSTEES In Pursuance of the Act of Incorporation 26 George II., Cap. 22, § xv. r 10th Decembei , 1898. PRINTED BY ORDER OE THE TRUSTEES LONDON : MDCCCXCYIII. PRINTED BY WOODFALL AND KINDER, LONG ACRE LONDON TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I. PAGE Meetings, Functions, and Privileges of the Trustees . 7 CHAPTER II. The Director and Principal Librarian . .10 Duties as Secretary and Accountant . .12 The Director of the Natural History Departments . 14 CHAPTER III. Subordinate Officers : Keepers and Assistant Keepers 15 Superintendent of the Reading Room . .17 Assistants . 17 Chief Messengers . .18 Attendance of Officers at Meetings, etc. -19 CHAPTER IV. Admission to the British Museum : Reading Room 20 Use of the Collections 21 6 CHAPTER V, Security of the Museum : Precautions against Fire, etc. APPENDIX. Succession of Trustees and Officers . Succession of Officers in Departments 7 STATUTES AND RULES. CHAPTER I. Of the Meetings, Functions, and Privileges of the Trustees. 1. General Meetings of the Trustees shall chap. r. be held four times in the year ; on the second Meetings. Saturday in May and December at the Museum (Bloomsbury) and on the fourth Saturday in February and July at the Museum (Natural History). 2. Special General Meetings shall be sum- moned by the Director and Principal Librarian (hereinafter called the Director), upon receiving notice in writing to that effect signed by two Trustees. 3. There shall be a Standing Committee, standing . • Committee. r 1 1 t-» • 1 t> 1 consisting 01 the three Principal 1 rustees, the Trustee appointed by the Crown, and sixteen other Trustees to be annually appointed at the General Meeting held on the second Saturday in May. -

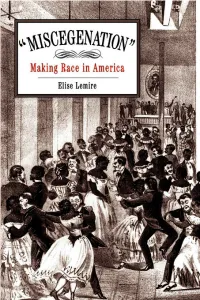

Miscegenation” This Page Intentionally Left Blank “Miscegenation” Making Race in America

“Miscegenation” This page intentionally left blank “Miscegenation” Making Race in America ELISE LEMIRE PENN UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PRESS Philadelphia Copyright © 2002 University of Pennsylvania Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Published by University of Pennsylvania Press Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4011 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lemire, Elise Virginia. “Miscegenation” : making race in America / Elise Lemire. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-8122-2064-3 (alk. paper) 1. American literature—19th century—History and criticism. 2. Miscegenation in literature. 3. Literature and society—United States—History—19th century. 4. Jeff erson, Th omas, 1743–1826—In literature. 5. Racially mixed people in literature. 6. Race relations in literature. 7. Racism in literature. 8. Race in literature. I. Title. PS217.M57 L46 2002 810.9'355—dc21 2002018048 For Jim This page intentionally left blank Contents List of Illustrations ix Introduction: The Rhetorical Wedge Between Preference and Prejudice 1 1. Race and the Idea of Preference in the New Republic: The Port Folio Poems About Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings 11 2. The Rhetoric of Blood and Mixture: Cooper’s “Man Without a Cross” 35 3. The Barrier of Good Taste: Avoiding A Sojourn in the City of Amalgamation in the Wake of Abolitionism 53 4. Combating Abolitionism with the Species Argument: Race and Economic Anxieties in Poe’s Philadelphia 87 5. Making “Miscegenation”: Alcott’s Paul Frere and the Limits of Brotherhood After Emancipation 115 Epilogue: “Miscegenation” Today 145 Notes 149 Bibliography 179 Index 191 Acknowledgments 203 This page intentionally left blank Illustrations 1. -

Using Te Reo Māori and Ta Re Moriori in Taxonomy

VealeNew Zealand et al.: Te Journal reo Ma- oriof Ecologyin taxonomy (2019) 43(3): 3388 © 2019 New Zealand Ecological Society. 1 REVIEW Using te reo Māori and ta re Moriori in taxonomy Andrew J. Veale1,2* , Peter de Lange1 , Thomas R. Buckley2,3 , Mana Cracknell4, Holden Hohaia2, Katharina Parry5 , Kamera Raharaha-Nehemia6, Kiri Reihana2 , Dave Seldon2,3 , Katarina Tawiri2 and Leilani Walker7 1Unitec Institute of Technology, 139 Carrington Road, Mt Albert, Auckland 1025, New Zealand 2Manaaki Whenua - Landcare Research, 231 Morrin Road, St Johns, Auckland 1072, New Zealand 3School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland, 3A Symonds St, Auckland CBD, Auckland 1010, New Zealand 4Rongomaiwhenua-Moriori, Kaiangaroa, Chatham Island, New Zealand 5Massey University, Private Bag 11222 Palmerston North, 4442, New Zealand 6Ngāti Kuri, Otaipango, Ngataki, Te Aupouri, Northland, New Zealand 7Auckland University of Technology, 55 Wellesley St E, Auckland CBS, Auckland 1010, New Zealand *Author for correspondence (Email: [email protected]) Published online: 28 November 2019 Auheke: Ko ngā ingoa Linnaean ka noho hei pou mō te pārongo e pā ana ki ngā momo koiora. He mea nui rawa kia mārama, kia ahurei hoki ngā ingoa pūnaha whakarōpū. Me pēnei kia taea ai te whakawhitiwhiti kōrero ā-pūtaiao nei. Nā tēnā kua āta whakatakotohia ētahi ture, tohu ārahi hoki hei whakahaere i ngā whakamārama pūnaha whakarōpū. Kua whakamanahia ēnei kia noho hei tikanga mō te ao pūnaha whakarōpū. Heoi, arā noa atu ngā hua o te tukanga waihanga ingoa Linnaean mō ngā momo koiora i tua atu i te tautohu noa i ngā momo koiora. Ko tētahi o aua hua ko te whakarau: (1) i te mātauranga o ngā iwi takatake, (2) i te kōrero rānei mai i te iwi o te rohe, (3) i ngā kōrero pūrākau rānei mō te wāhi whenua. -

Nomenclatural Studies Toward a World List of Diptera Genus-Group Names

Nomenclatural studies toward a world list of Diptera genus-group names. Part V Pierre-Justin-Marie Macquart Evenhuis, Neal L.; Pape, Thomas; Pont, Adrian C. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.4172.1.1 Publication date: 2016 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Document license: CC BY Citation for published version (APA): Evenhuis, N. L., Pape, T., & Pont, A. C. (2016). Nomenclatural studies toward a world list of Diptera genus- group names. Part V: Pierre-Justin-Marie Macquart. Magnolia Press. Zootaxa Vol. 4172 No. 1 https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4172.1.1 Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Zootaxa 4172 (1): 001–211 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Monograph ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2016 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4172.1.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:22128906-32FA-4A80-85D6-10F114E81A7B ZOOTAXA 4172 Nomenclatural Studies Toward a World List of Diptera Genus-Group Names. Part V: Pierre-Justin-Marie Macquart NEAL L. EVENHUIS1, THOMAS PAPE2 & ADRIAN C. PONT3 1 J. Linsley Gressitt Center for Entomological Research, Bishop Museum, 1525 Bernice Street, Honolulu, Hawaii 96817-2704, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Natural History Museum of Denmark, Universitetsparken 15, 2100 Copenhagen, Denmark. E-mail: [email protected] 3Oxford University Museum of Natural History, Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PW, UK. E-mail: [email protected] Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand Accepted by D. Whitmore: 15 Aug. 2016; published: 30 Sept. 2016 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0 NEAL L. -

Using Facial Angle to Prove Evolution and the Human Race Hierarchy Jerry Bergman

Papers Using facial angle to prove evolution and the human race hierarchy Jerry Bergman A measurement technique called facial angle has a history of being used to rank the position of animals and humans on the evolutionary hierarchy. The technique was exploited for several decades in order to prove evolution and justify racism. Extensive research on the correlation of brain shapes with mental traits and also the falsification of the whole field of phrenology, an area to which the facial angle theory was strongly linked, caused the theory’s demise. he use of the facial angle, a method of measuring but also the difference between the human “races”.8 Science Tthe forehead-to-jaw relationship, has a long history historian John Haller concluded that the “facial angle was and was often used to make judgments of inferiority and the most extensively elaborated and artlessly abused criteria superiority of certain human races. University of Chicago for racial somatology.”2 zoology professor Ransom Dexter wrote that the “subject of Supporters of this theory cited as proof convincing, the facial angle has occupied the attention of philosophers but very distorted, drawings of an obvious black African or from earliest antiquity.”1 Aristotle used it to help determine Australian Aborigine as being the lowest type of human and a person’s intelligence and to rank humans from inferior a Caucasian as the highest racial type. The slanting African to superior.2 It was first used in modern times to compare forehead shown in the pictures indicates a smaller frontal human races by Petrus Camper (1722–1789), and it became cortex, such as is typical of an ape, demonstrating to naïve widely popular until disproved in the early 20th century.2 observers their inferiority.